The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Booralee fishing town

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Booralee fishing town

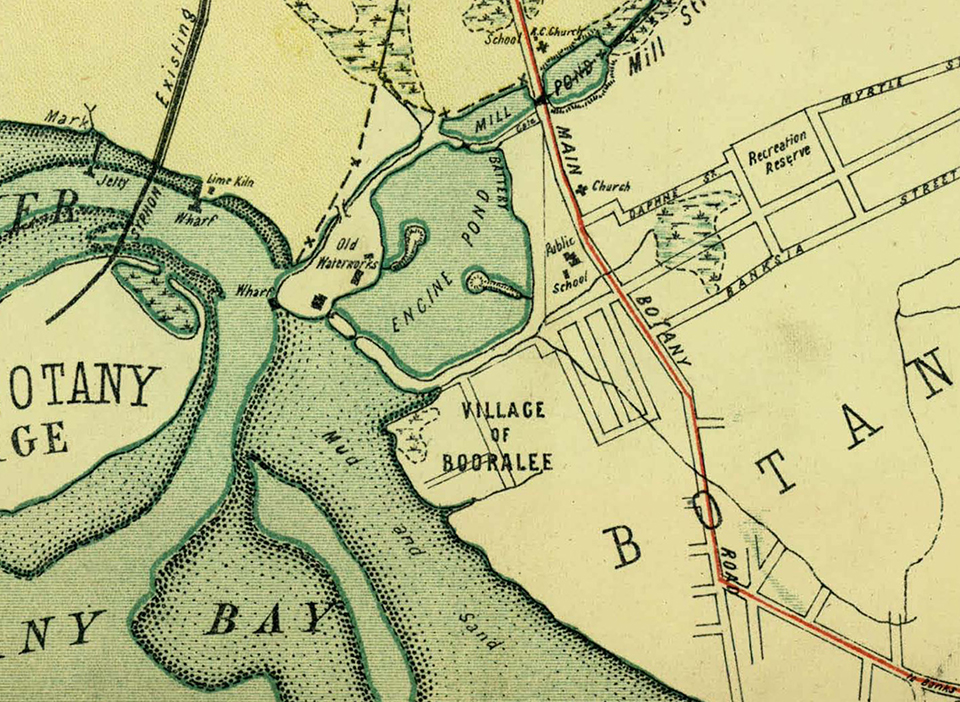

[media]The village of Booralee was a small cluster of streets in Botany where fishermen settled several decades after the arrival of the First Fleet. It stood on the northern foreshore of Botany Bay and adjacent to the mouth of the Cooks River on its eastern side. The streets of Bay, Booralee, Hale and Luland were the hub of the area. Fishermen's huts were erected seaward of the waterworks in the 1820s and it was seen as a romantic site, with the fishermen's lifestyle being very different to other colonial life in Sydney. [1]

The area was [media]dubbed 'fishing town' [2] in 1938 and housed about 200 inhabitants. The cottages were described as weather-beaten, having withstood the fiercest southerlies of Botany Bay. The town had thrived for over 100 years, supplying Sydney with a plentiful supply of fish harvested from Botany Bay. Many fishermen were descendants of English, Scottish and Welsh fishing folk and through the generations many of the families inter-married. Generations of fishermen made their living here and, removed from the bustle of Sydney, enjoyed living in their close-knit community. [3]

[media]There was a vibrant social life in fishing town. During the Depression, the Port Botany tin dinghy club races started on the bay, with sailing boats built from tin drums using clothes props for masts and household sheets for sails. [4] Sometimes there were 20 boats in a race and crowds of a hundred or more people watched from the beach. The clubhouse was a corrugated iron shed built on the foreshore and on most Saturday nights it was used for social dances. It was homemade entertainment – telling yarns, singing, dancing and playing various games like quoits or illegal 'two-up' with the inevitable raids by police. Club members called themselves the 'merry makers' and organised huge family picnics every year.

[media]By the 1930s, the era of prosperity for the professional fishermen at Botany was waning. Later descendants worked in local tanneries and wool scourers or moved away from the area altogether. The last of the fishermen left fishing town in the 1970s. Its demise was caused by a mix of overfishing and industrial development. The consequences of stricter fishing regulations and the major developments of Port Botany and Sydney Airport severed its close connection with the sea.

Today the area has no direct access to Botany Bay or the Cooks River, the cornerstones of its original existence. It is now bordered by Foreshore Road and Sydney International Airport. The weatherboard cottages of fishing town have largely been replaced by industrial sites, and only a few cottages remain in Booralee Street with several more in Bay Street and other connecting streets like Erith Street.

Fishing ground of the Kameygal people

Booralee [media]was the Aboriginal name for the area [5] with some later sources giving its meaning as 'burley'. [6] The Kameygal [7] people fished along a long beach of sand and mud flats that stretched far into the bay, and the shallow waters teamed with sea life. Middens dotted the beach and the banks of the Cooks River, evidence that it was an excellent fishing ground for the Kameygal people. [8]

Early written evidence of this ideal fishing ground is recorded by Captain Cook and others in their eight day visit to Botany Bay in 1770. [9] Even Cook knew it was but a glimpse of their lifestyle, as they never successfully met with the Aboriginal people and so knew little of their customs. [10] Yet 18 years later they were to be irrevocably displaced by the beginnings of the British colony at Port Jackson. A smallpox epidemic in 1789 devastated Aboriginal populations living near the early colony, with estimates that half perished. [11] In the years that followed, they were also moved off their traditional hunting grounds as the resources were commandeered for use by the new arrivals.

Europeans soon [media]encroached on the area around the Cooks River, attracted by the wooded land, the fish and the deposits of oyster shells. In 1881, a group of only 15 Aboriginal people were reported living in an Aboriginal camp at Botany with another group of 35 at La Perouse camp. These camps were visited by Botany Senior Constable, John F Byrne, who supplied them with rations including food, clothing, house building materials, boats and fishing tackle. [12] At the same time the camp at Botany was being 'eyed off' because it had become equally useful to the colonists. [13] By 1883, the people in the Botany camp were moved to the La Perouse camp or a mission station at Maloga on the Murray River. [14]

A delightful fishery

In 1809, Andrew Byrne, Mary Lewin and Edward Redmond were granted land on the Cooks River. Byrne collected the shells from Aboriginal middens which were burnt to extract lime and used to make mortar for the building industry. There was a limekiln and wharf built on the Cooks River soon after Sydney was established, which is mentioned by François Péron in his visit to the area in 1802. [15] When Andrew Byrne advertised his land for sale in 1819 it was described as situated on the banks of the Cooks River, commanding a full view of the ocean between Botany Heads and possessing a delightful and abundant fishery which supplied the Sydney market. [16]

Simeon Lord was another early [media]settler who dammed a local creek to establish a woollen mill in 1815, creating the Mill Pond. Portions of his 600 acre (243 hectare) grant near present day Booralee Street were formally subdivided as Booralee township in 1859 [17] and acquired by fishermen, some of whom were descendants of servants who had worked for Simeon Lord. [18]

[media]By the 1820s, Botany Bay mud oysters were taken to Sydney and fishermen had settled at the end of what is now Bay Street. [19] William Puckeridge (born 1802) and his brother John Puckeridge (born 1804) were lime-burners and net fishermen in the Botany area from about 1830 to the 1880s. The family kept their boats on a wharf in the Cooks River near the Engine Pond which became known as Puck's wharf. [20] William caught garfish in the Georges River and collected oysters which he sold to the popular oyster bars of Sydney. This was a boom period when the fishing industry was young and fairly unregulated. As the Sydney Mail complacently noted, 'Sydney, it is true, need not be at all alarmed for the supply of oysters in her market, for no sooner is the wealth of one river exhausted than the dredgers can turn to another....which has not yet been rifled.' [21]

Staked nets, sometimes a mile (1.6 kilometres) long, were set up on the mud flats inside the low water mark and when the tide fell the fish were trapped on the sand banks. Fishermen then just picked up the fish they wanted but left the rest to rot. Liming and dynamiting of fish in tidal waters also took place whereby the fish were poisoned or stunned for an easy catch.

The idea that a fishing ground could be plundered and then another found for the same purpose was losing traction in the second half of the nineteenth century. The same fishermen who harvested the waters of Botany Bay as if there was no tomorrow were realising the damage it caused. The first sign of overfishing and over-dredging was seen in the rapid depletion of the Botany Bay oyster stocks, in high demand by Sydney's food and building industries. By 1896, the mud oysters of Botany Bay were declared extinct.

Fishing regulations

Throughout the nineteenth century a series of Acts were passed in the NSW Parliament to regulate the fishing industry. These Acts limited the length and mesh size of fishing nets, closed fishing grounds that were overfished, regulated the size of fish caught and banned dubious fishing practices such as liming and stake-nets. Investigations into the fishing industry in 1880 still revealed Botany Bay as Sydney's most productive fishing ground but fears were emerging about its long-term survival.

As the Fisheries Inquiry Commission of 1880 noted:

Botany, though never equal to the Long Reef and Broken Bay grounds for school-fish, has always held its own for net-fish, indeed it is doubtful whether even Broken Bay, with its far greater extent of net grounds, has ever been or is now more productive than are the beaches and flats of Botany. This inlet, though shallow, covers many thousand acres of water, and as two salt-water rivers – George's and Cook's – flow into it, there is no lack of spawning or nursery grounds...Of course the processes of exhaustion common to all the grounds near Sydney have been in active operation at Botany, and especially that most destructive of all forms of fishery: the stake-net; yet notwithstanding all this, Botany is perhaps less impoverished considering the amount of fishing continually going on than any inlet or harbour within fisherman's distance of Sydney. But the evidence of witnesses well acquainted with the resources of Botany leads immediately to the conclusion that, unless arrested by legislative restraints, these prolific grounds will in a very short time succumb to the stake-nets and the small mesh as surely as our other fishing grounds have succumbed. [22]

[media]During the investigation, John Puckeridge admitted that he was the first man to destroy the stocks of garfish by netting the full width of the Georges River. After this inquiry, the Fisheries Act underwent a major overhaul in an effort to control the fishing industry more effectively. In practice the new rules of the 1881 Act had many pitfalls and were considered very harsh. [23]

As one inspector at the Sydney fish market commented:

I have known fish to be seized that did not come under the Act at all. I have known that to be done repeatedly with tarwhine, the weight of which is not mentioned in the Act....I have known Botany fishermen to lose several bushels of fine large bream for only having a dozen or so of small tarwhine among them; the whole of them have been seized. I thought it one of the cruellest things I ever saw....nearly £10 worth of fish [seized]. [24]

Frederick Woods, another Botany fisherman, bemoaned the fact that a catch of legally-sized bream could be seized if it had been caught in a garfish net. [25] In such cases, fishermen's nets were seized and locked up for months, thus depriving them of their livelihood. The new rules also imposed an annual fee of ten shillings per fishermen and £1 for a boat license, but the greatest impact to Botany fishermen was the closure of the Georges River in winter. They then had to leave their families for up to five months and head north to Tuggerah Lake and Lake Macquarie to continue to make a living from fishing. [26] In the face of such restrictions and harsh penalties, some Botany fishermen started to seek employment outside the fishing industry.

Traditional fishermen

[media]This was a major upheaval, as some families had been involved in the industry for generations. As the Sydney Morning Herald noted:

There are the Smiths, Duncans, Jones, Thompsons, Bagnalls and the Johnsons, whose fathers and grandfathers arrived in Sydney a hundred or more years ago. They carried on the traditions of their forbears in a new colony, and in all weathers pursued their calling: prawning and fishing. [27]

The Smith family was prominent in fishing town and their story reflects the experiences of many other fishing families [28]. Charles Smith Snr (born 1811) became a fisherman at Botany in the 1830s. His family lived at Pine Cottage, a weatherboard house he built at the bottom of Booralee Street, facing Botany Bay. He was part of the industry when fish were abundant and hauls of 100 baskets were common. One amazing haul of 1,000 baskets was taken at Botany, and the fish were kept enclosed by a net in the Bay and taken to market over three months. [29]

Two of the Smith sons, Charles Jnr and James, became professional net fishermen and several daughters married into other local fishing families. Charles Jnr (born 1845) entered the fishing trade with his father at the age of fourteen. By 1880, he had seen a tremendous increase in the number of boats fishing continuously on Botany Bay and was certain that this accounted for the scarcity of fish. [30]

In 1880, there [media]was talk of closing the whole of Botany Bay over winter but the fishermen protested that this would throw a good many of them out of work, as well as disrupting Sydney's fish supply. In the end, only the rivers were closed. Some families from fishing town survived these hard times, and in the early years of the twentieth century, the next generation started working.

Charles Smith Jnr had three sons who followed him into the fishing business and all settled in fishing town. Cuthbert (born 1883) started fishing with his father at a young age in the 1890s. The standard fishing boat was 20 feet long (6.1 metre) and 7 feet (2.1 metre) wide with 16 foot (4.8 metre) oars and a mast of about 10–12 feet (3–3.7 metre), with a light canvas sail. Hundreds of metres of rope and net would be piled in the back of the boat ready to be fed out over a wooden roller when 'shooting a haul' (encircling fish in the water in a large loop and then hauling the net in by hand). Cane baskets on board were used to scoop the fish from the net into the boat. Each basket held about 80 pounds (36.3kg) of fish and the boat could hold 30 basket loads. The boat would be 'on its gunnels' (sitting very low with water lapping the side edge) after such a catch.

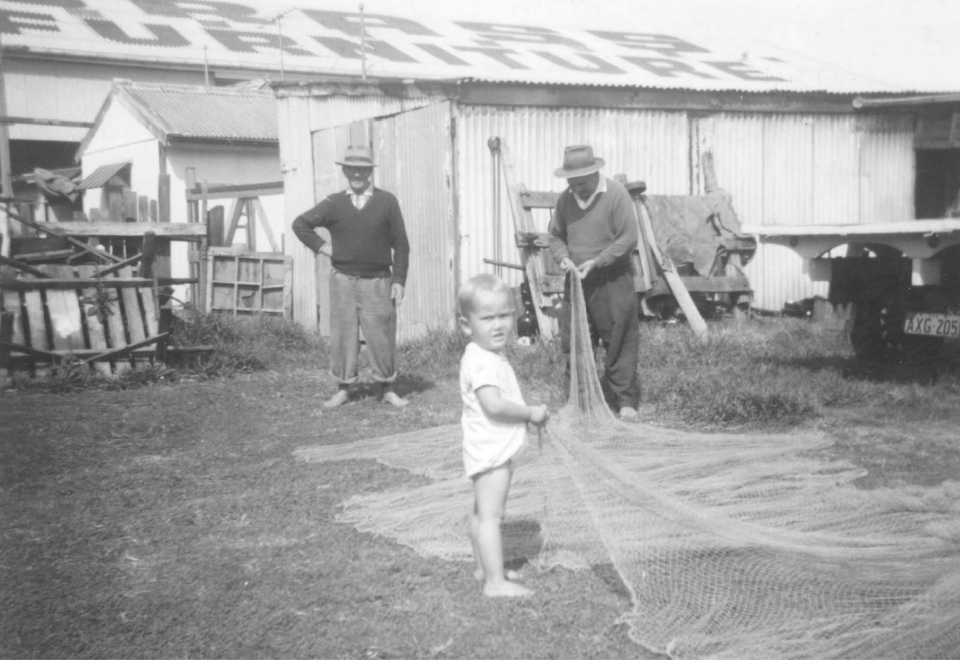

[media]Two of Cuthbert's sons, Leonard (born 1913) and Percy (born 1914), were the fourth generation of the Smith family at Botany – and the last professional fishermen from fishing town. Their fishing boat was called the P astime and moored on the mudflats near the end of Booralee Street. The boat was built in about 1913 and passed down from Cuthbert Smith to his sons. They still hauled the nets in by hand, as their ancestors had done before them, and sailed the boat or rowed it when there was no wind. They eventually fitted a single piston inboard motor – a rare concession to modernity. They were filmed for Bill Peach's television series about Australia in 1977 and he described the way they hauled their nets as being like a 'scene from the Bible. [31]

Fishing town was a remarkable [media]place that, to outsiders, seemed frozen in time with its traditional ways passed down through the generations. The Smiths, like other fishing families, lived through the dramatic changes that took place on the bay and witnessed the disintegration of fishing town until they left in 1979.

The loss of fishing town

[media]In the twentieth century, alterations occurred to the Botany foreshore and eventually fishing town lost its access to the waters of the bay and the Cooks River. In 1936, a seawall was built to halt erosion of the foreshore. This reclamation work was carried out from the government pier to the Cooks River as part of a work relief scheme towards the end of the Depression. Erosion may have lessened but the breakwater disrupted the route of the great shoals of mullet. [32]

The landscape also altered when two above-ground sewer systems were built in the 1920s and 1930s. They ran down Hale Street and along the foreshore of Botany Bay to service the southern and western suburbs outfall sewer scheme. The Hale Street sewer cut Luland Street in two and the eastern end was renamed McFall Street. [33] These sewer lines effectively ended easy access to the fishermen's boat moorings and the foreshore. The remaining fishermen now had to climb stairs over the sewer lines. Slowly but increasingly they were being disconnected from the sea. Fishing town was also rezoned as an industrial area at this time and homes were demolished to make way for new industrial complexes.

The proclamation of Botany Bay as a port of entry for overseas shipping in 1930 signaled the construction of oil tanker berths at Kurnell and the development of Port Botany. Further dredging for Port Botany in the early 1970s included the construction of Foreshore Road which cut off the precinct of fishing town from the bay once and for all. The original beachside of the Botany suburb disappeared.

[media]The expansion of Sydney Airport in the 1950s also had a major impact, when the original mouth of the Cooks River was filled in and diverted 1.6km westward for the first runway extensions. This was followed by more reclamation work for the second and third runways carried out in 1968, 1972 and 1994. The large dredging and reclamation operations caused long-term alterations to the wave action and tidal currents, in turn changing the sedimentation patterns. It also meant the loss of important seagrass beds which were the natural nurseries for fish.

All these developments made the fishing industry less viable in Botany Bay but the fishing town community had moved away long before the law banned all commercial fishing in Botany Bay from May 2002. In the streets today, the remaining fishermen's cottages stand amongst the industrial development that now marks the spot that was fishing town.

References

Botany Fishing Village website, Booralee Fishing Village Botany Bay, http://www.botanyfishingvillage.org, viewed 22 February 2013

City of Botany Bay Street Names Register, Botany Historical Trust, City of Botany Bay website, http://www.botanybay.nsw.gov.au/index.php/council-services/services/library-a-museum/botany-historical-trust, viewed 12 November 2012

'Aboriginal People and Place', Barani: Indigenous History of Sydney City, City of Sydney website, http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/aboriginal-people-and-place-2/, viewed 12 November 2012

'Daily entries, 27 July 1768–31 July 1771, 29 May–6 May, Botany Bay', Cooks Endeavour Journal, National Library of Australia website, http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/about.html, viewed 16 November 2012

The Fisheries and Oyster Fisheries Act, 1881 and the Regulations Thereunder, with an Introduction, Summary, and Index by Alexander Oliver, New South Wales Parliament, 1882

J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938

G Keep and G Wilson, Lauriston Park: The Forgotten Village, Botany Historical Trust, 1996

FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1970

Legislative Assembly New South Wales, Aborigines: Report of the Protector, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1882–1883

P Lipscomb and B Peach et al, Botany Bay, video, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Canberra, 1975

M Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen and Unwin, 2005

New South Wales Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Fisheries of this Colony, Report of the Royal Commission appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Actual State and Prospect of the Fisheries of this Colony: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1880

J Sippel, Booralee: The Lost Fishing Town of Botany, City of Botany Bay Council, 2003

'Kurnell: The Birthplace of Modern Australia', Sutherland Shire Environment Centre website, http://www.kurnell.com/home.htm, viewed 12 November 2012

The Fisheries and Oyster Fisheries Act, 1881 and the Regulations Thereunder, with an Introduction, Summary, and Index by Alexander Oliver, New South Wales Parliament, 1882

Notes

[1] Notes J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 58

[2] 'Fishing Town', The Sydney Morning Herald, 10 January 1938, p 8

[3] 'Work, Lifestyle and Culture', 'Around the Home', 'The Back Yard' and 'Food', Booralee Fishing Town Botany Bay, Botany Fishing Village website, http://www.botanyfishingvillage.org/pages/history/booralee-village-history.html, viewed 22 February 2013

[4] J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 367

[5] Australian Town and Country Journal, Saturday 14 September 1889 and Northern Star, Saturday 11 August 1900

[6] 'History', 'Early Enterprises' and 'Fishing', Kurnell: The Birthplace of Modern Australia, Sutherland Shire Environment Centre website, http://www.kurnell.com/home.htm ,viewed 12 November 2012

[7] Distribution of Linguistic Tribes in the Sydney Area in 1788, 'Aboriginal People and Place', Barani: Indigenous History of Sydney City, City of Sydney website, http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/aboriginal-people-and-place-2/, viewed 12 November 2012

[8] G Keep and G Wilson, Lauriston Park: The Forgotten Village, Botany Historical Trust, 1996, p 4

[9] 'Daily entries, 27 July 1768–31 July 1771, 29 May–6 May, Botany Bay', Cooks Endeavour Journal, National Library of Australia website, http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/about.html, viewed 16 November, 2012

[10] 'Daily entries, 27 July 1768–31 July 1771, 29 May–6 May, Botany Bay', Cooks Endeavour Journal, National Library of Australia website, http://southseas.nla.gov.au/journals/cook/about.html, viewed 16 November, 2012

[11] 'Aboriginal People and Place', Barani: Indigenous History of Sydney City, City of Sydney website, http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/aboriginal-people-and-place-2/, viewed 12 November 2012

[12] Legislative Assembly New South Wales, Aborigines: Report of the Protector, To 31 December, 1882) New South Wales Parliament, 1883

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 17 January 1883

[14] M Nugent, Botany Bay: Where Histories Meet, Allen and Unwin, 2005, p 48

[15] J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 53

[16] Advertisements, The Sydney Gazette, Saturday 6 March 1819, p 2

[17] J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 64 and p 69

[18] FA Larcombe, The History of Botany 1788–1970, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1970, p 59

[19] J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 57

[20] G Keep and G Wilson, Lauriston Park: The Forgotten Village, Botany Historical Trust, 1996, p 32

[21] The Sydney Mail, Saturday, 9 September 1871, p 893

[22] New South Wales Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Fisheries of this Colony, Report of the Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Actual State and Prospect of the Fisheries of this Colony: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1880, p 25

[23] New South Wales Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Fisheries of this Colony, Report of the Royal Commission Appointed on the 8th January, 1880, to Inquire Into and Report Upon the Actual State and Prospect of the Fisheries of this Colony: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1880,, p 3

[24] Richard Seymour, Inspector and Auctioneer of the Sydney Fish Market cited in New South Wales Legislative Assembly Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act, Report from the Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act: Together With the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1889, pp 115–123

[25] Frederick Woods, Botany fisherman cited in New South Wales Legislative Assembly Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act, Report from the Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act: Together With the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1889, p 10

[26] 'Family traditions' in J Sippel, Booralee: The Lost Fishing Town of Botany, City of Botany Bay Council, 2003

[27] The Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 10 January 1938, p 8

[28] J Sippel, Booralee – The Lost Fishing Town of Botany, City of Botany Bay Council, 2003; 'Booralee – the Lost Fishing Town of Botany' lists other family names of Botany fishermen sourced from the Fisheries Inquiry Commission 1880 and Working of the Fisheries Act 1881; 'The Families of Fishing Town' provides brief family histories

[29] J Jervis and L Flack, A Jubilee History of the Municipality of Botany 1888–1938, The Council of the Municipality of Botany, Sydney, 1938, p 59

[30] Charles Smith Jnr, Botany fisherman cited in New South Wales Legislative Assembly Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act, Report from the Select Committee on Working of the Fisheries Act: Together With the Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices, New South Wales Parliament, Sydney, 1889, p 19

[31] P Lipscomb and B Peach et al, Botany Bay, video, Australian Broadcasting Commission, Canberra, 1975

[32] 'Fishing Town', The Sydney Morning Herald, Monday 10 January 1938, p 8

[33] City of Botany Bay Street Names Register, Botany Historical Trust, City of Botany Bay website, http://www.botanybay.nsw.gov.au/index.php/council-services/services/library-a-museum/botany-historical-trust, viewed 16 November 2012, p 63