The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras

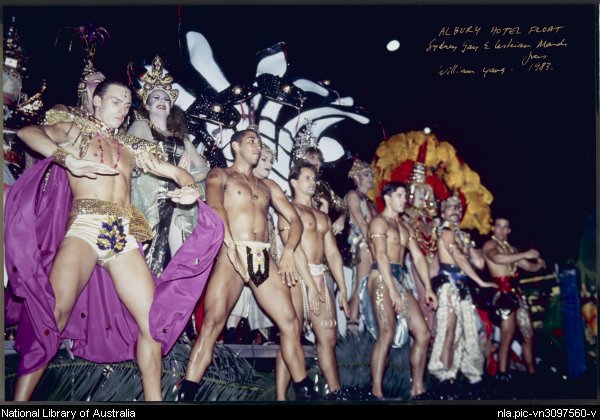

It was a [media]parade of 15,000 people through the streets of Sydney on a warm Saturday night in late February. There were 52 floats, numerous cars and trucks, sundry other vehicles, and vaqueros on horseback, and, as one watcher noted,

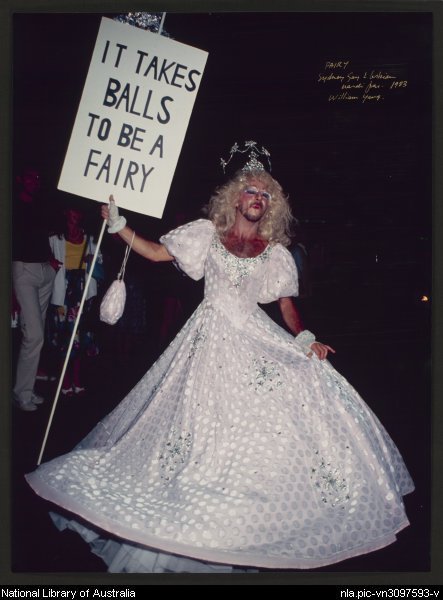

bikies, Darth Vaders, cycle sluts, gladiators, Red Indians, Supremes, Carmen Mirandas, wizards, fairies, ballroom dancers, nuns and altar boys.

Others were wearing just enough 'to keep them out of the Darlinghurst slammer on indecent exposure charges'. [1] Tens of thousands of people lined the streets, hundreds more crowded out onto balconies and awnings, bands and disco music blared, and searchlights and spotlights played on buildings and the low clouds. It was the 1983 Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade.

Yet [media]this parade – probably the largest parade not associated with war that had passed through Sydney's streets – received no coverage as news by any of the mainstream newspapers or TV channels in Sydney. Envious Melbournians at least got a later report in the Age: its commentator bemoaned the fact that such an event 'put Melbourne's Moomba parade in the shade'. [2]

Legal status of gay Sydneysiders

The [media]paradox of such an event in Sydney receiving so little mainstream news coverage highlighted the ambivalent situation of the city's gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgendered inhabitants (now referred to as GLBTQ: queer has since been added in) in the early 1980s. While they were given some protection by the state's anti-discrimination laws, male homosexuals among them were still subject to laws that criminalised their emotional and sexual life.

Such an anomaly did, of course, bring forth actions and reactions, focussing initially on decriminalising male homosexual behaviour, as had occurred in 1980 in Victoria, when Rupert Hamer's Liberal Party government had acted on this issue. But the laws in New South Wales relating to male homosexual behaviour had last been amended in the 1950s, but only to make them more draconian. During the Cold War, authorities in many western countries had grave concerns about various 'minorities' that they regarded as potential threats to national security. The Sydney Superintendent of Police, Colin Delaney, argued that the two greatest threats facing Australia at that time were communism and homosexuality.

In 1951, the laws relating to male same-sex behaviour – imprecisely named 'the abominable crime of buggery' – already carried a sentence of 14 years in gaol. An amendment added the clause 'with or without the consent of such person' to one subsection. This was to avoid any legal argument about whether consensual sex between two men constituted 'assault'. [3]

In late 1954, with Delaney in the position of New South Wales Police Commissioner, a new set of amendments to the law were proposed and passed. It now became a crime to ask another man to have consensual sex; penalties for both the existing and new provisions were increased; and one amendment allowed for the suppression of any details of such cases of 'sex offences' coming before the courts. While the Attorney-General argued that these details were to be suppressed because they were 'repulsive to many people – particularly parents of adolescent children' [4] – others in the community, including lawyers and newspaper editors, thought differently. [5] In their view it was as much to protect police who acted as agents provocateurs – inciting men to make a pass at them so that they could then arrest them. But the tenor of the times was such that the loss of civil liberties for homosexual men was seen as a small price to pay.

These laws were still on the books 30 years later. Public attitudes to homosexuality had changed, and as social activism increased from the late 1960s, these draconian laws became the focus of increasingly vocal attempts at reform. There were ongoing and concerted efforts from the early 1970s, especially after the formation of a range of gay groups whose aims were law reform, education of the wider public and support for male and female homosexuals. But there was no dramatic event to act as a catalyst and bring to a head the work of gay activists, civil libertarians, progressive lawyers and influential commentators. That event came in Sydney on the night of Saturday 24 June 1978.

The first Mardi Gras parade 1978

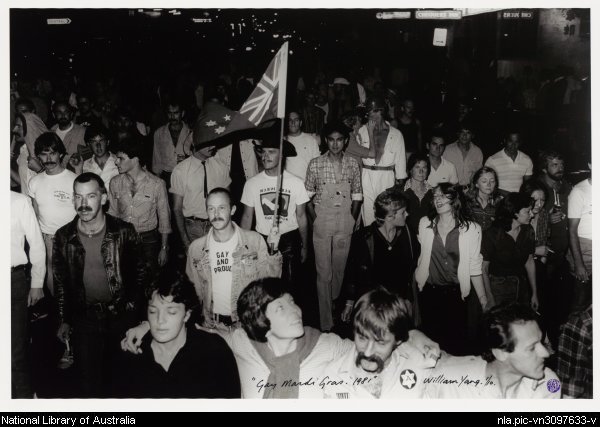

[media]The day had been set aside by Sydney's GLBTQ communities as part of a world-wide International Gay Solidarity Day, to commemorate the Stonewall Inn riots that had occurred in New York in June 1969. In Sydney, there was to be a march in the morning, a public meeting in the afternoon, and then a 'fiesta' and parade that evening.

Crowds gathered at Taylor Square at about 9.30 pm. Police had given approval for a parade down Oxford Street to Hyde Park, where there would be the usual speeches. However, as the parade drew close to Whitlam Square, the police stopped the parade, confiscated the lead truck with the public address system, and told the marchers to disperse.

The crowd did not take kindly to this police intervention, which was hardly surprising given the strained relations between the two groups. By mutual consent among the marchers, they began to make their way along College Street to William Street, and up to Kings Cross, the traditional home for outré Sydneysiders. In the face of this intransigence, police radioed for reinforcements, making plans to lock the marchers in between two police lines in Darlinghurst Road at the Cross.

But the marchers gathered supporters along the way, and the police misjudged the mood of the growing crowd. Kings Cross erupted, and in the ensuing melée many more onlookers joined in, hurling garbage bins, bottles and cans at the police. What had started as a parade to commemorate a riot in New York nine years earlier became a full-scale riot in Sydney

Sydneysiders were somewhat taken aback at the turn of events, not that they were unaware of the thuggish behaviour of the police. As The Australian reported the next day:

At 10.30 pm Australia's first homosexual Mardi Gras was in full swing, with about 1000 people singing and dancing down Sydney's Oxford Street, caught up in the excitement of a jubilant crowd.

One hour later, the mardi gras had become a two-hour spree of screaming, bashing and arrests.

In one incident, police took off their identification numbers and waded into a crowd of homosexuals.

Fifty-three people were arrested during the pitched battle between police and marchers, these latter joined by onlookers who had little cause to love or respect the state's police. [6]

What happened next exacerbated the situation. When those arrested appeared at the city's Central Court of Petty Sessions a few days later, a huge contingent of police blocked access into the chamber. Despite the magistrate's decision that the court be opened to the public, the police forcibly restricted access, effectively closing the court. This led to further clashes, with another seven people arrested.

TV news cameras captured these images, which flashed across the world, and once again drew attention to the role of the New South Wales police, embarrassing the state Labor government of Premier Neville Wran, a lawyer who had claimed to be a staunch upholder of civil rights.

Repercussions of the march

Further embarrassment came from the court cases. In the first case heard, the magistrate accepted evidence from impartial witnesses, including an ABC television cameraman, and after seeing film of the event that contradicted police evidence, he dismissed the case. But damage to individual reputations had begun, with the names and addresses of all those arrested being published in the Sydney Morning Herald, with unfortunate consequences for many. After the court loss, the police decided to drop the other cases.

In the following weeks, the embarrassing publicity continued. Demonstrations were held around Australia, protesting against heavy-handed police actions. In Adelaide, the incidents had widespread TV and radio coverage, and demonstrators gathered outside the New South Wales tourist office, warning visitors against travelling to a 'police state'. In Melbourne, there was also media coverage, and a public demonstration in support of those arrested.

And the furore went on, gathering momentum. A couple of weeks later, at a march in Sydney protesting against the original arrests, police again intervened, arresting another 14 people. Further demonstrations – and police responses – followed: on 27 August, another protest march ended in another clash, with 104 people arrested. More demonstrations occurred in the following months. Various civil liberties groups, long concerned about the police's arbitrary use of their public assembly control powers, took up the cause.

The initial march and its aftermath, and the developments that followed, were a very public example of the problems that gay citizens of New South Wales faced. With civil liberties groups involved, there was even more publicity, and attention was increasingly focussed on the role of the police, a longstanding problem in New South Wales. Indeed, police behaviour in this case was important in helping force the state government to curtail police powers. In May 1979, the Summary Offences Act was repealed, removing the main instrument with which police arbitrarily controlled who could walk the streets of Sydney.

Decriminalisation at last

The issue refused to die down. Gay activists and civil libertarians pressed the government over the following years to change the laws, in line with public opinion polls showing that a majority of Australians were not against decriminalising male homosexual behaviour. But the government was reluctant. Partly this reflected the considerable power of the Catholic and Anglican churches as lobby groups; partly it reflected the conservatism of the members of the state Labor government.

The crisis came at a Council for Civil Liberties dinner, when the New South Wales Premier rose to give a glowing speech about his government's achievements in the field of civil liberties. The response was not what he expected. As one witness remembers it, bread rolls and abuse were hurled at the Premier, amid catcalls about gay rights and the abuse by police of their powers. Since the Premier was also the Police Minister, it was all seen as his responsibility.

Premier Wran's way around this dilemma was to bypass the party, and introduce a private member's bill to decriminalise male homosexual acts for those above the age of 18.

The debate when the bill was introduced was acrimonious, with prophecies that the Christian God would be displeased and would wreak destruction on the state. But with support from progressives from all parties – and despite adamant opposition from the die-hards – the bill was passed into law. So in 1984, the year after the parade that opened this entry, male homosexual acts were decriminalised. That first Mardi Gras had achieved its objective.

Mardi Gras goes mainstream

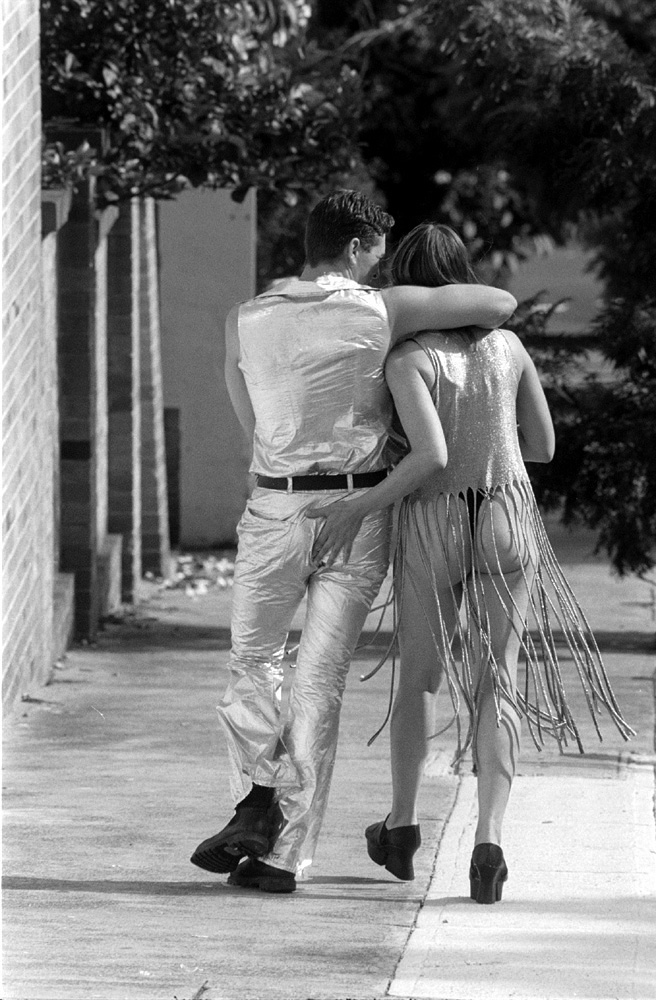

[media]In its early years, the parade was a highly politicised event. Would the police act against a group that had defied them? But the government was aware of the changing public perception of what was now known as Sydney's 'gay' community, and police intervention was discouraged. Over time, as the parade was shifted to the warmer end of summer, its numbers swelled, and the marchers took satirical aim at many of society's sacred cows, the Mardi Gras came to have a special place in Sydney's cultural life. It didn't hurt that it also became a major tourist attraction, drawing thousand of overseas visitors and boosting the state's economy to the tune of many millions of dollars.

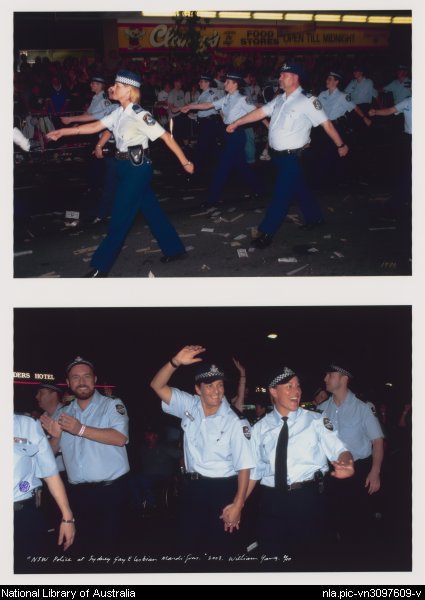

But today, the parade is a pale imitation of its past glories. Over the years, several new entrants to the parade have been welcomed as symbolic of the changed perceptions of homosexuals in our society –this [media]group includes the New South Wales Police Service. However, other recent entrants, such as banks and commercial enterprises, would not have been seen associating with anything that smacked of homosexuality, only a few years previously. For them, the GLBTQ communities have become purely a marketing target, and Mardi Gras a highly visible opportunity to show their wares.

Another development also helped diminish the 'in-your-face' character of the parade. When it was decided to cover the Mardi Gras with a live TV transmission, there was pressure to remove 'offensive' material. Of course, what is offensive usually lies in the eyes of the beholder: one wit noted that the Reverend Fred Nile, of the Festival of Light, had misread the Bible, and wanted Sydney to become a place, not where sheep may safely graze, but at which sheep may safely gaze. In the 30 parades that have occurred so far, Nile and others have prayed for rain to wash away this 'abomination in the sight of God'. But the much prayed for rain has fallen only three times, and has never led to the parade being abandoned.

Now the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade is just a spectacle, a parade of dressed-up queens and their supporters and hangers-on, walking through the streets of Sydney, a cultural event open to all and sundry, with any political content purely accidental.

But perhaps the current form of the parade reflects another aspect of gay life in Sydney – that the city's GLBTQ communities are no longer seen as the dreaded and feared 'other'. While this may be so, it also might imply that, with such acceptance, the 'gay sensibility' – that outsiders' take on an uncomprehending society – has gone.

References

Graham Carbery, A history of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, Australian Lesbian and Gay Archives, Parkville Vic, 1995

Garry Wotherspoon, City of the Plain: history of a gay sub-culture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

Notes

[1] Leo Schofield, Sydney Morning Herald, 26 February 1983

[2] The Age, 21 February 1983, p 5

[3] G Wotherspoon, City of the Plain: history of a gay sub-culture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, ch 2 and 3

[4] New South Wales Parliamentary Debates, 23 November 1954, p 1874

[5] Sydney Morning Herald, 17 November 1954, editorial, p 2; New South Wales Parliamentary Debates, 23 March 1955, pp 3,248–50, 3,252

[6] Amanda Wilson, 'How a carnival turned into a vicious brawl', Australian, 26 June 1978, p 1

.