The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Germans

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Germans

German-speaking people have played a small but significant part in the history of Sydney. In [media]fact the colony's first governor, Arthur Phillip, was of German-English parentage: his father, a German teacher in London, came from the Hessian town of Frankfurt. Philip Schaeffer, the supervisor of the First Fleet, was also of Hessian background, as was Augustus Alt, the first Surveyor of Lands in New South Wales. Alt played an important part in the design and construction of Sydney during the first ten years of European settlement. On retirement both men joined the ranks of the colony's early free settlers.

Early German settlers

The [media]number of Germans among the convicts was small – only six are listed to have been of German origin – although an attempt on the part of the Hanseatic city of Hamburg to empty its jails by shipping the inmates to New South Wales was spoilt only at the last minute. [1] By the 1820s a number of German merchants and wool-buyers had settled in Sydney and by the 1830s, prominent pastoral family the Macarthurs had brought out several shepherds and winegrowers. The latter, who came from Germany's Rheingau region, planted the colony's first major vineyards on the south-western outskirts of Sydney.

Scientists also arrived at this early stage of the city's history. Astronomer and marine scientist Christian Karl Ludwig Rümker arrived in 1821 to take charge of Governor Brisbane's private observatory at Parramatta. He was appointed Government Astronomer and given 1,000 acres (405 hectares) of land as reward for his rediscovery of the 'Encke-planet', a comet whose orbit had recently been calculated, but whose return was only observable in the southern hemisphere. Although he was granted further generous land allocations, he returned to Hamburg in 1830 to take over the directorship of the Hamburg School of Navigation. Prague-born Franz Wilhelm Sieber was the first German botanist to collect Australian plants. He arrived in Sydney in 1823, stayed for seven months, and left with 300 collected plants.

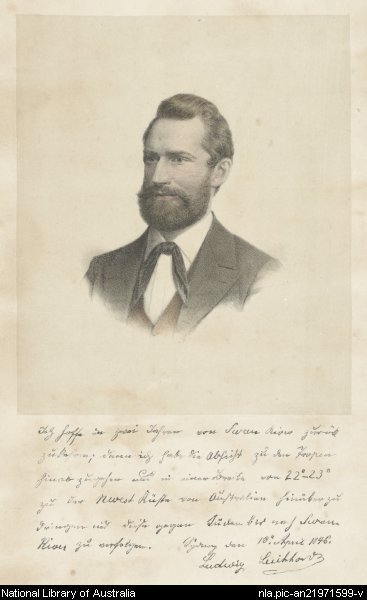

The most famous of the German scientists and [media]explorers in Australia, Ludwig Leichhardt, embarked for Sydney on 26 October 1841 and the city became his chief place of residence for the time he was not out exploring the Australian inland. His diaries list frequent visits to the small German community that had settled by the 1840s. In Sydney he was able to raise the financial backing for his three major explorations: the northeast crossing of the continent in 1844–45 – the first abortive attempt to cross the whole of Australia (December 1846–June 1847) – and the second and fatal attempt to achieve the continent's east–west crossing that he commenced in March 1848.

Assisted immigration

The colony's regulations allowed immigrants from the European continent to qualify for the bounty immigration scheme only in exceptional circumstances, but when these regulations were lifted in the early 1840s, the door to large-scale immigration from Germany was opened.

The first German immigration agent was prosperous merchant Wilhelm Kirchner, again from Frankfurt in Hessia, who arrived in Sydney in November 1839 to set up business. To solve the colony's growing labour shortage Kirchner submitted a bounty scheme for subsidised German immigration that granted a family an initial income of £20–25 per annum. The immigrants were contracted to work for a period of time – normally two years – for the person who had paid the bounty. They were then free to go their own way.

Over the next ten years, Kirchner brought out around 4,000 migrants under this scheme. Some of them settled on the outskirts of Sydney where they worked as vinedressers for the Macarthurs near Camden or at the Cox family vineyard near Penrith. On completion of their contracts many were able to buy their own land at reasonable prices for viticulture, orchards or market gardens. The majority of the German newcomers, however, preferred to move into the colony's rural hinterland. [2]

The discovery of gold in the eastern states led to a further rush of Germans to Australia: 31,000 were estimated to be present by 1861, more than a third of them on the goldfields. Rural families and gold seekers continued to arrive in the colony for the rest of the nineteenth century.

By the end of the nineteenth century approximately 10,000 people in New South Wales were listed to have been born in German-speaking countries (this figure does not include their dependants). Most of them were still living in the country. [media]Many worked in the service industries and in skilled trades such as printing, cabinetmaking and tailoring. Germans were also well represented in the city's small business community, as shopkeepers, salesmen or restaurant owners, and in the entrepreneurial class: a number of import, merchant and manufacturing firms were in German hands. They abounded among musicians and were well represented among architects and artists. A number of second- and third-generation Germans were teachers, chiefly in primary and secondary schools. They were under-represented, however, among lawyers and doctors.

Famous Germans in Sydney

A number of German speakers achieved fame and wealth in Sydney. Johannes Nepomuk Degotardi, of Graz in Austria, arrived in Sydney with his wife in 1853 at 30 years of age, and established a successful printing, publishing and photographic business. He edited the first German-language newspaper in Sydney, published a highly acclaimed book about the art of printing, and was among the city's first photographers. Johann Korff, son of a Brunswick family, set up a flourishing shipping business. [media]Edmund Resch arrived with his brother Emil from Dortmund in 1863. After a successful spell of copper mining at Cobar he started the Lyon Brewery in Wilcannia with his younger brother Richard. Business at this hot outback town was so good that Edmund was soon able to move to Sydney where he founded the Resch's Brewery – for a century Sydney's most famous beer maker.

[media]It was rare for citizens of German background in Australia to make it into political office, but Bernhardt Otto Holtermann, originally from Hamburg, held the New South Wales Legislative Assembly seat of St Leonards from 1882 until his sudden and premature death in 1885. Born in 1838, he arrived in Australia at the age of 20. He tried his luck on the goldfields around Bathurst for over 12 years before fortune finally came his way. In October 1872 he was part of a group of prospectors who discovered the world's largest specimen of reef gold, weighing almost 300 kilograms. Holtermann did not squander his sudden wealth but invested his money wisely. He moved to Sydney where he built a magnificent house for his family at St Leonards overlooking the harbour and the city. [media]For the rest of his life Holtermann was able to devote all his time to his great passion – photography – and won international fame with his pictures of the goldfields and the countryside, and especially the magnificent panoramic shots of Sydney, for which he was commissioned. Today his photographs provide us with an excellent record of life in Sydney at that time.

Germans loved clubs and club-life. In the last decades of the nineteenth century they founded numerous skittle clubs, rifle associations, brotherhoods of skat players (a popular German card game), and above all, choral societies. [media]Only one of these, however, reached longevity: founded in 1883, the German Concordia Club has seen its 125th anniversary. Only the German Evangelical Church in Sydney, which began services in 1866, can claim a longer history as an organisation providing for the needs and interests of German-speaking communities in Sydney.

The effect of World War I

The arrival of German aggressive colonialism right at Australia's doorstep, coupled with attempts by Imperial Germany's Consulate-General in Sydney to spread the message of Deutschtum (the superiority of German culture and tradition) among the German population, began to sour Australian-German relations at the beginning of the twentieth century, and eroded the positive image that had surrounded German settlement here. Prior to the outbreak of World War I, Sydney's German-speaking community would have been around 2,500. World War I had a devastating impact upon many Germans, including, of course, Sydney's German community. Most German nationals were interned because of national security considerations and for their own security. [3] The Australian authorities, however, were not consistent with their internment policies and not all people of German background were victimised.

Fritz Müller, for example, had arrived in Sydney in 1885, when he was four years old. He set up a small soldering and car repair shop in Crown Street, Surry Hills, a few years before the war. After August 1914 Müller changed his name, and that of his company, to Fredrick Muller. He did such good business during the war that he was able to set up a much larger plant in Parramatta Road, Camperdown, and became Australia's leading cooling-system manufacturer. It was important during the war years not to rock the boat.

Dr Maximilian Herz, an outstanding physician and surgeon, did rock the boat. He was greatly perturbed that his new country was at war with his original homeland and found it very hard to accept the prevailing anti-German atmosphere. Herz expressed his feeling in a number of letters, which were intercepted, and a diary which was confiscated by the censors, leading to his internment in Trial Bay camp, in northern New South Wales. After the war he became the target of a particular nasty campaign by the Australian branch of the British Medical Association to have him deported to Germany. They probably wished to settle old scores: Herz had severely criticized the standards of the Australian medical profession at various prewar conferences. The attempt, however, failed.

Nazism and refugees

After World War I, German immigration was banned until 1925 and did not pick up again until the latter half of the 1930s. The slow improvement in Australian-German relations came to a quick end when Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1933. There was a small but very active Nazi movement in Sydney, strongly supported again by the German Consulate-General, but it made little progress with attempts to win over the local German community. In particular the Concordia Club successfully resisted the spread of Nazism among its members. However, the murderous racial and political policies of Nazi Germany soon led to a sharp increase in Sydney's German-speaking population.

Around 7,000 German-Jewish people, or people declared to be Jews under the notorious Nazi racial laws, managed to escape from Europe and reach the safe shores of Australia before it was too late. Approximately 2,000 came from Vienna, a city of great cultural tradition. These refugees soon proved to be a blessing for the continent in all walks of life. Sydney and Melbourne were fortunate to receive the lion's share of the escapees from Nazi barbarism.

[media]Viennese Harry Seidler, for example, established an outstanding international reputation as an architect. Richard Goldner, also a Jewish refugee from Vienna, was the founding father of the Sydney Musica Viva, the principal chamber music network and one of the foremost music organisations in the country.

[media]Stefan Haag was stranded in Australia in 1939 when singing with the Vienna Boys Choir. He was the principal singer with the National Theatre Opera Company before he became executive director for the Elizabethan Trust Opera from 1956–69. Then 'this complete man of the theatre, singer, director, producer, lightning and set-designer' [4] worked for the Tivoli, Sydney's new cabaret-restaurant, promoted successful productions such as Hair and Jesus Christ Superstar and promoted Aboriginal theatre.

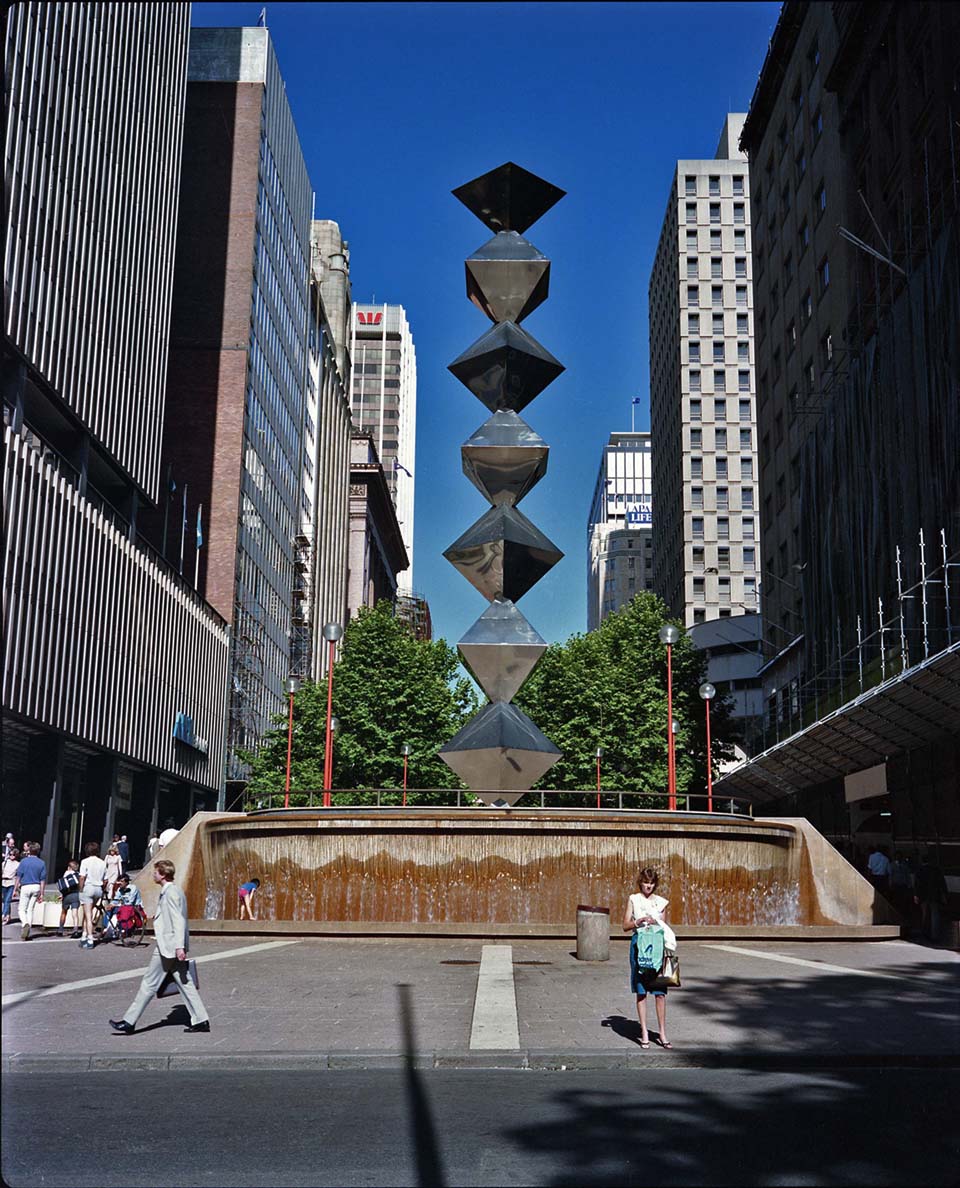

[media]One of Australia's best known sculptors, Bert Flügelmann, arrived from Vienna in 1938. After the war Flügelmann taught art at East Sydney Technical College, the University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales.

Other refugees established successful businesses. Charles Berg, born into a Berlin Jewish family, left Germany in 1936 and did very well after the war as an accountant and banker. In addition he was, for many years, first secretary then president of Musica Viva and from 1974–86 Chairman of the Australian Opera.

Bernd Hammermann came from a long line of fur traders. He arrived in Sydney in 1937 where he set up his own fur business in 1941, which grew to include retail outlets all over the continent. As a man of culture he worked tirelessly as a patron of the arts and to bring Australia closer to the 'New Australians' – as the postwar immigrants were called in the 1950s. In 1952 he was foundation member of the Sydney All Nations Club, an organisation that at its peak had 1,400 members, and in 1972 was appointed first governor of the Power Foundation.

Postwar immigration

[media]In 1952 Germans were included in Australia's postwar assisted immigration scheme. Over the next 20 years, 150,000 migrants arrived from the Federal Republic of Germany, in addition to about 30,000 Austrians and German-speaking Swiss. The rising living standard in these countries, however, led to a very high return rate – approximately one-third returned to Europe. Change in Australian immigration policies in the early 1980s ensured that German immigration over the last 25 years has rarely exceeded 1,000 per annum and the return rate remains high.

[media]Unlike their predecessors in the nineteenth century, the majority of the postwar German-speaking immigrants did not settle in the country but in the big cities, above all Sydney and Melbourne. The census over the last few decades consistently lists about 25,000 people born in German-speaking countries. They are scattered evenly over the city with only Woollahra reaching a level of 1 per cent.

[media]Again German immigrants quickly assimilated. As the leading Australian population expert James Jupp aptly comments, Germans 'settled into suburbia very quickly and quietly, becoming "invisible" by their conformity to established Australian norms'. While skilled and semi-skilled migrants predominated at first, new immigration criteria meant that by the late 1970s German-speaking immigrants were often well-to-do or came with special skills or experience. Their income distribution and education levels ranked highly compared to most other ethnic groups. [5]

The Concordia Club, almost finished after World War II, saw two decades of flourishing revival during the 1950s and 1960s. A magnificent club building at Stanmore was evidence of the club's wealth at that time. As club members became more affluent, they moved into 'nicer homes' away from the inner city. As the postwar German immigrants aged, their descendants had little interest in becoming club members. The migrants who arrived in the final quarter of the twentieth century did not identify themselves with the club's goal of preserving traditional German Gemütlichkeit. Not surprisingly there was a gradual decline in the club's fortunes. Today Concordia is housed in modest premises at Tempe, still offering Gemütlichkeit to all Sydneysiders.

German culture's contribution to Sydney

Most of Sydney's 25,000-strong German-speaking community have contributed to the city's growth and prosperity and cultural diversity. Irmhild Beinssen, President of the Australia-German Welfare Society, gave invaluable service to the community for over 30 years. The Goethe Institute in Woollahra, currently headed by Dr. Arpad Sölter, ensures the maintenance of Australian-German cultural and intellectual relations. Austrian Rudi Krausmann's poetry is receiving widespread recognition, as are the works of Wolfgang Gresse, a leading representative of the Vienna School of modern fantasy art. Marlene Norst and Konrad Kwiet are among the many academics who have contributed to Sydney's intellectual life.

Germans continue to arrive in Sydney at a steady rate, whether for professional or private reasons, or because the place is such an attractive and stimulating place to live in. This means that the decline in numbers experienced by many other immigrant communities from northern and eastern Europe is not likely to occur among those with German-speaking backgrounds.

References

P Cloos (ed), 'Greetings from the Land where Milk and Honey Flows': The German Immigration to New South Wales 1838–1858, Southern Highlands Publishers, Canberra, 1993

Jürgen Tampke, The Germans in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 2007

M Jurgensen, (ed), German-Australian Cultural Relations since 1945, Peter Lang, Bern, 1995

Notes

[1] J Perkins and J Tampke, 'The convicts who never arrived: The Hamburg Senate and the Australian Agricultural Company', The Push from the Bush, April 1985, pp 244–255.

[2] P Cloos, (ed), 'Greetings from the Land where Milk and Honey Flows':The German Immigration to New South Wales 1838–1858, Southern Highlands Publishers, Canberra, 1993, pp 21–47

[3] J Tampke (ed), 'Ruthless Warfare'. German military planning and surveillance in the Australian-New Zealand region before the Great War, Southern Highlands Publishers, Canberra, 1998, pp 7–34;J Tampke, The Germans in Australia, Cambridge University Press , Melbourne, 2007, pp 111–126

[4] G Stilz, 'German Australian Academic Relations Since 1945', in M Jurgensen, (ed), German-Australian Cultural Relations since 1945, Peter Lang, Bern, 1995, pp 163–4

[5] J Jupp, 'The Hidden Migrants: German-Speakers in Australia Since 1950' in M Jurgensen, (ed), German-Australian Cultural Relations since 1945, Peter Lang, Bern, 1995, pp 63–75

.