The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Kings Cross

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Kings Cross

Just where is Kings Cross?–or, as it is referred to affectionately by those who live there – The Cross. Can anyone say, or point to it definitely, or define its boundaries?[1]

Kings Cross [media]exists in Sydney's imagination as much as it does in any physical form. Since the 1940s, it has developed an almost mystical reputation as the centre of Sydney's seedy red-light district, attracting thrill seekers, party-goers and the down-and-out equally. Today's fading bohemian façade reflects the area's earlier incarnation as home to many of Sydney's artistic and literary citizens. However, Kings Cross itself, as a physical place, takes up a much smaller portion of the city than its reputation suggests, for much of what is referred to as the Cross is in fact part of its neighbours – Potts Point, Darlinghurst and Elizabeth Bay.

Where is the Cross?

In 1963, Kenneth Slessor noted that people who 'go to the Cross' or 'live at the Cross' could mean anywhere from Taylor Square to Wylde Street, but this didn't matter as they were expressing a state of mind. The Cross was a term rather than a place, its boundaries were flexible. If the actual locality is taken literally, then Kings Cross is in fact a very small place, essentially the intersection of Victoria and Darlinghurst roads at the top of William Street. Much like the reputation it later developed, from the very start the Cross was shrouded in controversy, power and politics.

William Street was constructed in the early 1830s to allow ease of access to the newly erected mansions along the ridge line of Woolloomooloo Hill, recently renamed Darlinghurst by Governor Darling. Darlinghurst was to be Sydney's first exclusive suburb, set aside by Darling for the colonial elite to build government-approved mansions. By the mid-1830s, 17 houses had been erected, all costing at least £1,000.

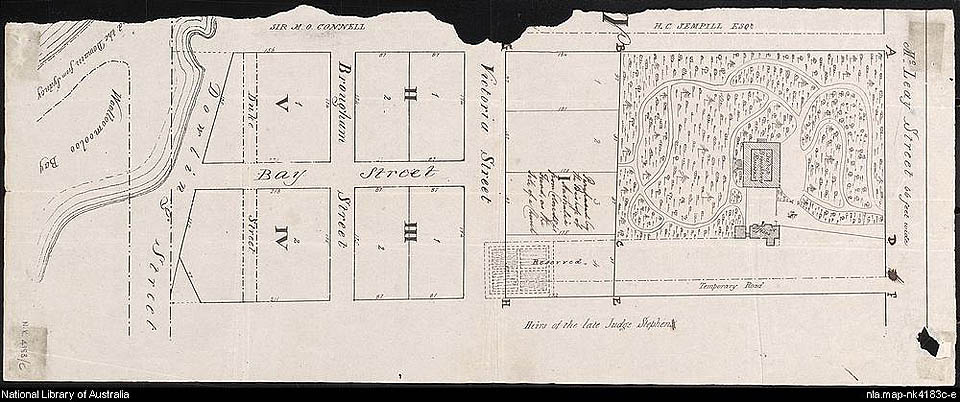

[media]The wealthy colonial merchants, officials and gentlemen who resided in the gleaming white mansions that dotted the ridgeline of Darlinghurst had to drive their carriages via South Head Road (later Oxford Street) to Darlinghurst Road to access their businesses in town. With this in mind, Surveyor-General Sir Thomas Mitchell, who owned one of the Darlinghurst villas, proposed a street to be named after William IV. Mitchell's proposed street followed the easiest gradient up the hill but would have crossed the property boundary of the miller Thomas Barker's estate, and supposedly compromised the properties of his influential neighbours Thomas West and Alexander Macleay, the Colonial Secretary. [2]

Barker had no intention of forgoing any of his land, while Macleay was equally reluctant to have the new main street running close to his residence. While Mitchell was out of Sydney on a surveying expedition, Macleay ordered the new street to be put through in a direct line heading east from Park Street. This took the street up the steepest, but shortest, path to intersect with Victoria Street and Darlinghurst Road at the top of the ridge. Two further streets, to be named Upper William Street North (Bayswater Road) and Upper William Street South (Kings Cross Road) were put in place to carry traffic over the ridge while skirting the boundaries of the private estates. The new road junction, prepared against the advice of Mitchell to serve the interests of property owners, proved to be a bane to Sydney commuters for the next 140 years, until the opening of the Kings Cross tunnel in December 1975. The road was too steep for horse carts and omnibuses and the junction at the top was one of the worst traffic bottlenecks in the entire city. It did however form a cross which eventually gave the area its name.

In 1897, the junction of Victoria Street, Darlinghurst Road, William Street and Upper William Street was named Queens Cross, in honour of the jubilee of Queen Victoria. [3] Queens Cross lasted just eight years. The City Council changed the name to Kings Cross in 1905, to avoid confusion with Queens Place (now Queens Square) near Hyde Park and to recognise the change of monarch. Still, for some residents the change took a little longer to make, with the funeral director Charles Kinsela still advertising his business as the top of William Street, Queens Cross, as late as November 1906. [4]

The wider Cross

Of course, for most Sydneysiders, any mention of the Cross conjures a wider geographical area than the intersection of four roads. For many people, the Cross refers to the larger zone from the top of William Street, along Darlinghurst Road to Macleay Street, down Bayswater Road to Elizabeth Bay Road and north along Victoria Street into the edges of Potts Point. This is now 'the Cross', with its bars and clubs, sleaze mixed with sophistication and sensation.

Europeans first moved into the outskirts of the future Kings Cross from 1810, when Thomas West was granted land to build a water mill. West named his land, measuring approximately 40 acres (16.2 hectares), Barcom Glen and used his mill to supply flour to the colonial bakers and community. Although West's mill stood to the south of Kings Cross, in Darlinghurst, it was one of the first permanent European structures erected in the area. By the 1820s, West's mill had been joined by a number of windmills, built on the ridge line that extended from the South Head Road (now Oxford Street) north towards the harbour. The most prominent mills were those belonging to Thomas Barker and the one built adjacent to Thomas Mitchell's property, Craigend. [5]

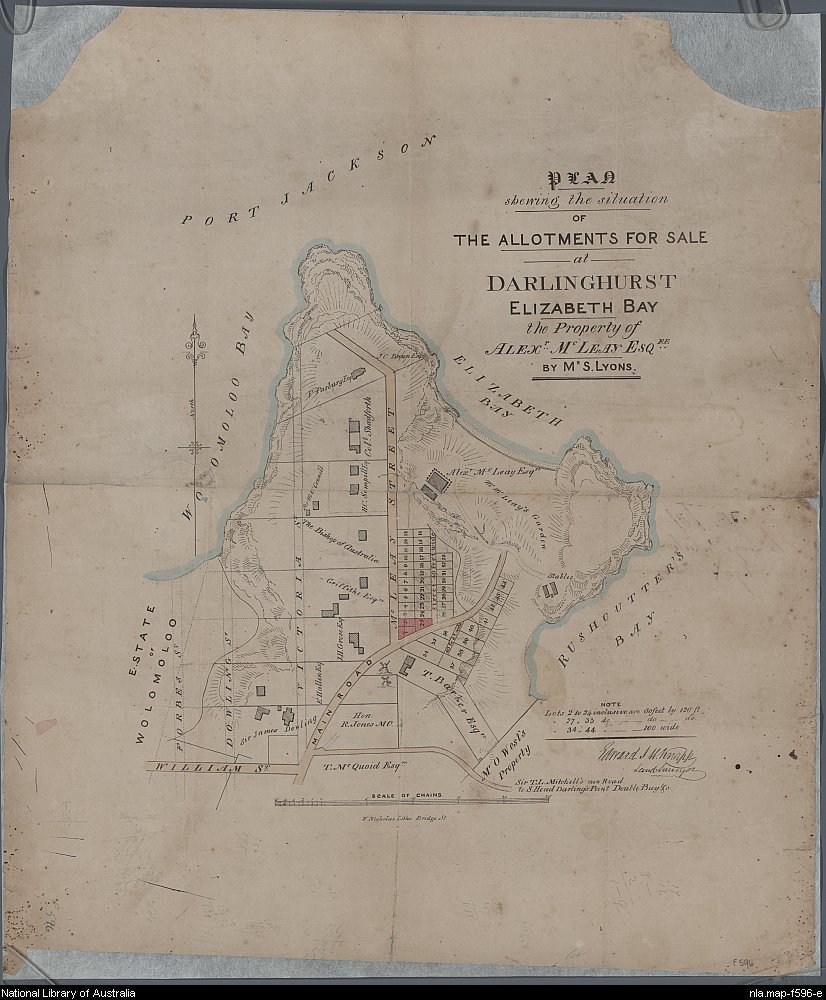

This [media]industrial development occurred in conjunction with the first grand residential vision for the area, Governor Darling's Darlinghurst. Of the 17 villa estates laid out by Darling on the ridge line, six fell within the area now referred to as Kings Cross: James Dowling's Brougham Lodge, Alexander Baxter's Springfield Lodge, Augustus Perry's Buona Vista, Thomas Macquoid's Goderich Lodge, Thomas Barker's Roslyn Hall estate with its windmills, and Edward Hallen's nine-acre (3.6-hectare) grant on which he did not build. The villas and properties were reached by Darlinghurst Road, running north from South Head Road.

The owners were required to landscape their properties and the villas, when completed, were prominent features on the eastern skyline, although they did not necessarily represent any taming of the colonial landscape. In February 1833 a fire in the bush on Woolloomooloo Hill burnt for three nights, no doubt causing some concern among the newly installed residents. The Sydney Gazette noted that it had a most splendid appearance from a distance, commenting that

It seemed like an illuminated garden in which the trees were laden with innumerable brilliant lamps. [6]

Governor Darling's original [media]plan for these estates was that they would serve as an example to the wider population of what could be achieved in Sydney, and as a showcase of the growing prosperity of the colony. However, by the late 1830s the first subdivisions were being prepared. In 1837 Thomas Mitchell was first to subdivide, breaking up his Craigend Estate.

The Cross develops

With the [media]onset of an economic depression in the early 1840s, sale notices for new allotments being made out of other villa estates soon began appearing with regularity in the local newspapers. The subdivisions encouraged the first speculators and developers to start buying and building townhouses and smaller villas across the ridge-top. New streets were laid out to access the growing number of allotments for sale, including Victoria Street which was created in 1837. To the east of the ridge, Alexander Macleay began to subdivide his Elizabeth Bay estate, with 40 allotments created from September 1841, forming Elizabeth Bay Road and Macleay Street in the process. [7] A number of large townhouses were erected on these blocks, of which Maramanah was later the best known, as it became a hub for Sydney society in the early 1900s and the subject of Robin Dalton's 1965 memoir Aunts up the Cross .

By 1854, allotments for sale spread along the west side of Darlinghurst Road, with a few terrace-style buildings erected on them. In Victoria Street, allotments had been set out down both sides for much of its length, and houses had been constructed at its southern end, close to the Darlinghurst Road junction. Despite the subdivisions, much of the land remained open and undeveloped through the 1850s, and all of the original villas were still standing, as were at least three windmills. In 1860, an observer remarked that the mansions surrounded with their park-like gardens prevented even the appearance of impertinent intrusion, despite the erection of more modest dwellings on their borders. [8]

From the 1860s [media]through to the 1880s the future Kings Cross filled with houses as the estates were subdivided further. Darlinghurst Road's density increased enormously from 1861, when 14 residents were listed between Macleay Street and William Street, to 1880 when 43 were listed, with most of the development coming on the eastern side, following the construction of the Roslyn and Alberta Terrace buildings. Development across Kings Cross was not consistent, but composed of a mix of single-storey cottages and two- to three-storey terraces. Victoria Street reflected a different demographic, with smaller worker-style terraces at its south end around William Street, growing to larger townhouses with views over the harbour at its northern end.

During the economic depression of the 1890s, increasing numbers of the larger terraces and townhouses were converted for use as boarding houses or residential chambers, as the cost of keeping such big houses turned into a burden for owners. Their proximity to the city, and the number of rooms that could be let as bedrooms, made them ideal for use as boarding or lodging houses for the ever-increasing city population. Boarding houses provided accommodation for a range of city dwellers, from transient residents to newly arrived migrants, for single men or women, and for skilled workers. They were places where skilled workers could stay while trying to get a foothold in the city economy. [9]

As well as providing accommodation, the boarding houses provided employment for women, and most of them were run by women. For every man described as employer, wage-earner or self-employed in boarding and lodging houses in 1911, there were six women, with 58 per cent of the total number of women engaged in the business being employers, and the rest employed as cooks or cleaners. [10] Although these statistics are for the wider Sydney area, the inner city held the majority of boarding houses with the highest density in Kings Cross, Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo.

In 1890 there were 17 boarding houses in the Kings Cross area, one in Kellett Street, three in Upper William Street South (Kings Cross Road) and 13 in Victoria Street. Of these, only one was run by a man. By 1905 the number had risen to 55, of which 48 were run by women, and by 1915 the number of boarding houses or residential chambers in Bayswater Road, Darlinghurst Road, Kellett Street and Victoria Street had risen to 165, of which 139 were run by women. [11]

From the 1920s, a [media]dramatic change in the residential character of the area began to take place, as new flat and apartment buildings were constructed across the Kings Cross area. Whereas the boarding houses and residential chambers had largely occupied existing buildings, flats and apartments were built new, resulting in the demolition of many earlier buildings to make way for them. During the 1920s, the principal area for flat development in Sydney was within the City of Sydney, with Kings Cross the most developed. In 1926 a quarter of all flats built in the greater Sydney area were built in Kings Cross. [12] A large proportion of these developments were six to eight stories high, using the 'new' technology of 'lifts', and they resulted in the appearance of a striking new skyline along the ridge above Darlinghurst and Woolloomooloo.

Kings Cross calling

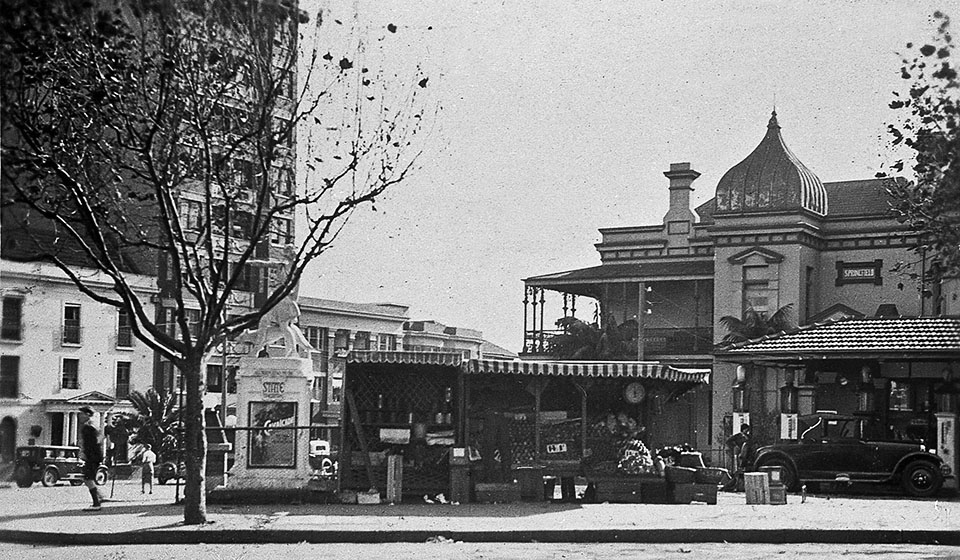

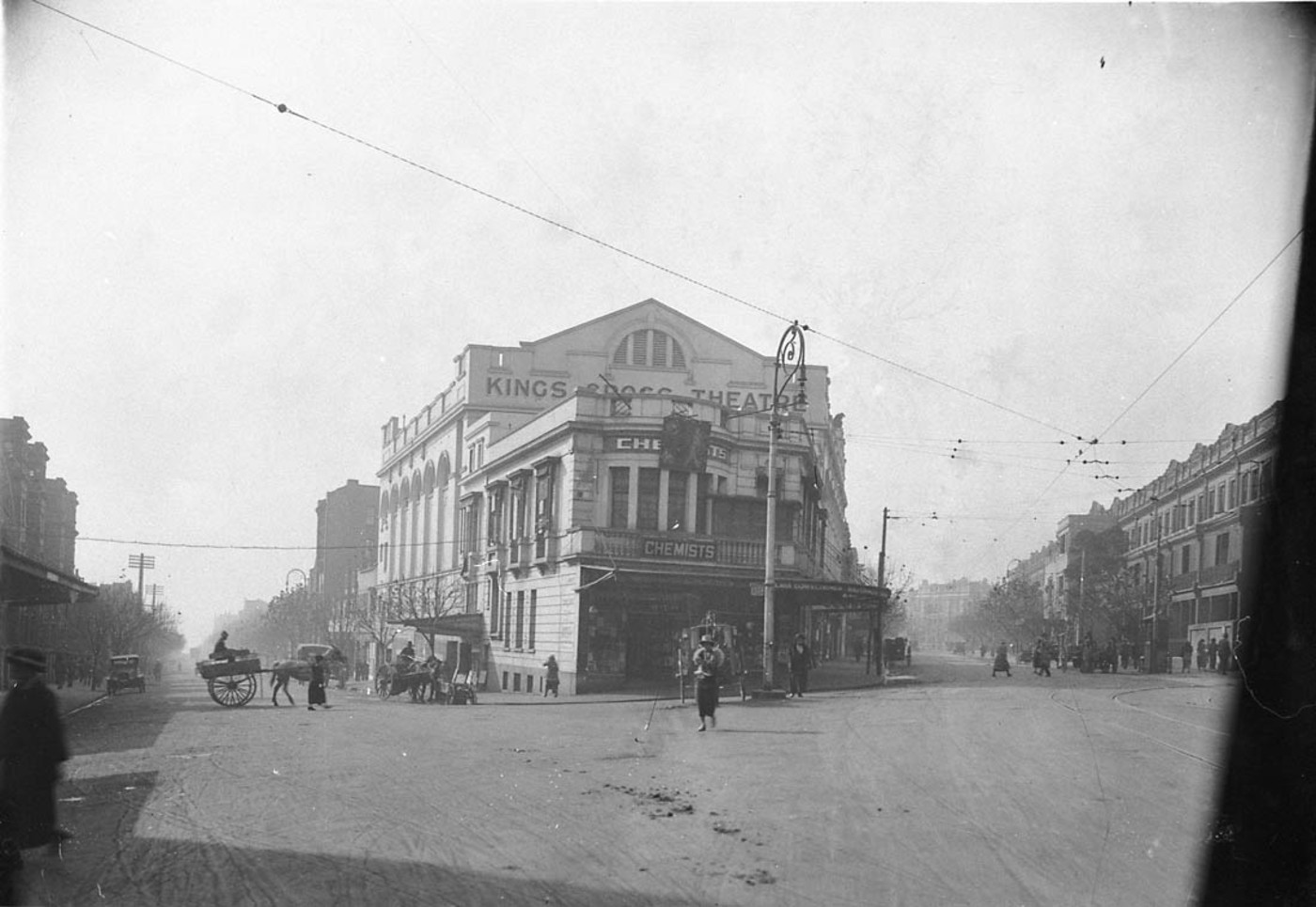

[media]The rising number of flats and the associated rise in population also changed the commercial sector. From the 1920s through to the 1940s, Kings Cross was a very modern place, streaking ahead of the rest of Sydney, not just physically with its new apartment-style living but also in its food and entertainment options, its gaudy new neon advertising signs and its increasingly liberal attitude to life and living. While groceries, fruit shops and 'ham and beef shops' catered to the residents of the area, Kings Cross began to develop a reputation for night-time entertainment and dining, and an increasing number of cafés, restaurants, saloons and entertainment venues also began to open. The Kings Cross Theatre had opened at the apex of Darlinghurst Road and Victoria Street in 1916, with cafés and restaurants soon appearing to take advantage of the theatre's drawing power. The Paris Café and John Psaltis's fish and oyster saloon in Darlinghurst Road, and Samuel Lever's Refreshment Rooms, HS Gilkes's wine saloon and Mrs Payton's dining rooms, all in Victoria Street, were all trading by 1925. The Kings Cross Theatre was a hub for a number of venues, with billiard rooms, oyster saloons, and cafés all trading within a few doors of it.

The cafés became a focus for an increasingly bohemian atmosphere in the Cross. The California Café, opened in 1929 by American Dick McGowan, was a gathering place with impromptu recitals and performances held inside its painting-lined walls, while the Café Eldorado in Darlinghurst Road and the Darlinghurst Liberal Club hosted political meetings and rallies. [13] A number of the cafés became local landmarks, such as the Kookaburra Café, famous for its cakes, which traded for over 25 years, while others such as the Pekin café run by Charlie Lee, and the Claremont run by German émigré Walter Magnus, introduced an exotic, international flavour to the dining experience. By the start of World War II, the cafés and restaurants in the area had helped establish a cosmopolitan reputation for the Cross. Late night dining could be enjoyed at Harold's (Italian), the Soho or the Silver Grill which included outdoor dining. The Hamburger served meals to late night revellers in William Street, while the Hasty Tasty introduced an Americanised version of the fast food café from 1940, serving burgers, grills and coffees just in time for the influx of United States servicemen during the war.

As well as the cafés and restaurants, the Kings Cross area attracted a range of delicatessens and specialised grocery stores to cater to an increasingly ethnically diverse population. By 1930 the New South Wales Jewish War Memorial Hall and the Swedish Club were both operating in Darlinghurst Road, with the Greek Consul-General in Elizabeth Bay Road. The mix of nationalities in the Cross became more pronounced through the 1930s, as the area became popular with newly arrived migrants escaping the growing threat of fascism in Europe. In 1939 the Sydney Morning Herald commented that Kings Cross was the most self-contained of Sydney's suburbs, 'where foreigners have largely modified our social customs to produce an international settlement'. [14] As the population diversified, so did the types of food in the restaurants and cafés. The residents of the Cross were the vanguard of Sydney's take-away eating culture. Butchers and 'Ham and Beef' shops, otherwise known as delicatessens, sold pre-cooked meals. Businessmen and women could pick up baked rabbits, frankfurts, chicken and ham rissoles, Cornish pasties, and chicken pies or steaks from Dunbars, Booths or Wolfe's. [15]

European migrants continued to be attracted to the Cross throughout the war years and into the postwar period. In 1952, with increasing numbers of migrants entering Australia, the All Nations Club was established by Sir Robert Garran at 50 Bayswater Road, with a mission to help new Australians to assimilate. The club provided a meeting place for members, with bars, restaurants and theatre and a regular newsletter Welcome, which documented the club's activities. [16] By the late 1970s the club had diversified its activities and was home to The New Group Theatre, opened in 1978 under the direction of the Aboriginal director Brian Syron.

The international scene was part of the wider bohemian feel that pervaded the Cross. From the 1920s, artists, writers, musicians and performers had been drawn to live in the flats and apartments or the old converted terraces and town houses. Poets such as Dame Mary Gilmore, Kenneth Slessor and Christopher Brennan all lived there, as did writers George Johnston and Charmian Clift, and Dymphna Cusack, who later reported that her time living in Orwell Street in 1941 helped with her novel Come in Spinner.[17] The artist William Dobell lived on the corner of Darlinghurst Road and Roslyn Street for a few years in the early 1940s, with Russell Drysdale and Donald Friend living nearby. Swiss-born Australian War Artist Sali Herman lived in Potts Point from 1941. He won the 1944 Wynne Prize for his painting of McElhone Stairs.[18] Later, self-styled [media]witch and artist Rosaleen Norton was a well-known figure about the streets. Sculptor Arthur Fleischmann and painter Justin O'Brien lived in a boarding house in Potts Point, while sculptor Robert Klippel had a studio in the stables of Wyldefel in Potts Point later in the 1950s. [19] Actors Peter Finch and Chips Rafferty were other notable residents in the 1930s and 1940s. Walter Magnus's Claremont café was a particular favourite with Kings Cross artists, with its wall decorated by Elaine Haxton. Finch, Drysdale, Friend and others were regulars. [20] Later in the 1950s, the Terry Clune Gallery in Macleay Street continued the bohemian ideal with emerging 'radical' artists such as Russell Drysdale and John Olsen. The Clune Gallery was later transformed into an artists' collective reminiscent of the 1920s scene, when Martin Sharp opened the Yellow House in 1970. Based on Vincent Van Gogh's ideal collective, Sharp and his artistic band painted the exterior bright yellow and covered its internal walls with murals, portraits and decoration. Artists such as Brett Whiteley, Bruce Goold and Peter Kingston turned the building into an art work, while visiting bands and celebrities made it a regular fixture of the Sydney scene.

Writers such as Slessor wrote eloquently and poetically about their life in and around the Cross, evoking its bohemian nature as well as the edgier side that was emerging. In the journal Home in 1923, Slessor as 'The Prisoner of Darlinghurst' penned a tongue-in-cheek critique of his new home, claiming it a place better to explore than live in and yet living there all the same. Sights and sounds differentiated the place from the rest of Sydney. Kings Cross was a place filled with

bottle-ohs, limousines, paupers' funerals, police patrols, millionaires, American actresses, mysterious screams, and people who don't pay their taxi-fares. It is a stone chasm echoing with romance and adventure – and hidden drunks.' [21]

During the same period Slessor was writing about, a seedier side was emerging, as the razor gangs, thugs and standover men previously associated with Surry Hills and Woolloomooloo began to creep into the area, taking advantage of the late night scene. Despite the many layers of use and occupation of the Cross through the twentieth century, it is the reputation of the Cross as a seedy, edgy underworld, apart from the usual social morés of Sydney, that has held the public attention. From 1916 pubs closed at six o'clock, which produced a flourishing sly-grog scene in Sydney and Kings Cross. A number of the daytime cafés were caught out in raids during the 1920s and 1930s, while a series of late-night venues, night clubs and illegal casinos sprang up during the same period.

The increasingly lucrative trade in illicit fun encouraged more brazen attempts at turf control. Running gang wars, assaults and shootings became a scourge of the area in the 1920s and 1930s. A battle in Eaton Avenue followed by a riot in Kellett Street in May and August of 1929 brought the growing crime scene to the headlines. Both incidents included shots fired and some of Sydney's most notorious underworld figures, such as Phil 'the Jew' Jeffs, and the henchmen of Tilly Devine and Kate Leigh were involved. Jeffs was a well-known figure in the Cross in the later 1920s and through the 1930s, peddling cocaine and running sly grog dens and night clubs such as the 50-50 Club on William Street.

The heady mix of underworld figures and artists made Kings Cross a tourist destination in its own city. The Sydney Morning Herald summed it up in 1939, saying:

By day, Kings Cross is distinguished by the excellence of the shopping centre along Victoria Street. There you can buy furnishings, eat well and patronise grocers who go in for black bread and sausages with the names that sound like Napoleon's victories. Globetrotters entering these shops shut their eyes while they recapture memories of Vienna.

After dark the district becomes gay and slightly sinister. Fine cars give way to taxis and the sleepy cafés become smoky, noisy and feverish. The Bohemians and the underworld emerge from their lairs at about eight o'clock when the blanket of the dark encourages them to take the air. Certain cafés are recognised as virtually clubs for different grades of moon-worshippers. [22]

The real and imagined goings on at the Cross – criminal, artistic, political or culinary – attracted suburbanites and interstate tourists for a look at least, as well as those wanting to escape to what they perceived to be the more liberal lifestyle on offer.

As a [media]place of refuge or escape, Kings Cross attracted many who suffered in its streets from violence, homelessness and addiction, especially from the 1970s. In response, a number of organisations also sprang up to save the Cross, most notably the Wayside Chapel, founded by Ted Noffs. Opened in 1964 as a coffee house above Noffs's Methodist Chapel, the Wayside quickly established itself as a hangout for 'beatniks' and other marginal groups of young people in the area. In 1965 it began addressing wider social issues, opening a crisis centre for drug addicts, followed in 1967 by a drug referral centre. These were forerunners (by a long way) to the Kings Cross Injecting Room which opened in 2001.

A night out

The cosmopolitan feel of the Cross was enhanced by the growing range of entertainment options from the 1920s. The opening in 1916 of the Kings Cross Theatre, a picture palace showing movies and newsreels, marked the start of the area as an entertainment precinct. The Kings Cross Theatre was converted into a live music venue, Surf City, in the early 1960s, catering to the growing rock 'n' roll scene in Sydney. By 1924 the theatre had been joined by Ciro's cabaret at the top of William Street, with regular dances, and by Maxim's cabaret in Darlinghurst Road. [23] Cabaret scene a popular late night activity in Sydney more generally, although the concentration of venues that appeared in Kings Cross through the 1920s and 1930s made cabaret particularly evident in this part of the city. Darlinghurst Road between Victoria Street and Macleay Street was viewed by some as Sydney's answer to the West End of London, Charlottenburg of pre-war Berlin, or even the Montparnasse café district of Paris. [24]

The larger cabaret halls were supplemented by the cafes which remained open into the evening. By the mid-1930s these were also joined by a growing number of smaller venues, nightclubs and jazz bars offering meals and entertainment and, increasingly, alcohol. Breaches of the Licensing Act by venues serving alcohol in Kings Cross were regularly reported in the daily papers through the 1930s and 1940s. The year-round entertainment was supplemented from the later 1930s by huge celebrations to herald the New Year. From at least 1937, Kings Cross became one of the main focal points for Sydneysiders to gather to see in the New Year, with thousands of people flocking in, clogging the streets and preventing trams, buses or cars from moving through. In 1940 the crowds were so great, estimated at 40,000 or more, that

At the hour of midnight it seemed as though a revolution was about to start … the cheering and shouting from thousands of throats, the blowing of trumpets and other noisemakers set up a cacophony which could be heard throughout the city. [25]

Kings Cross remained the main centre for New Year celebrations in Sydney for the next 40 years, until the establishment of the Festival of Sydney began to refocus the night towards the harbour.

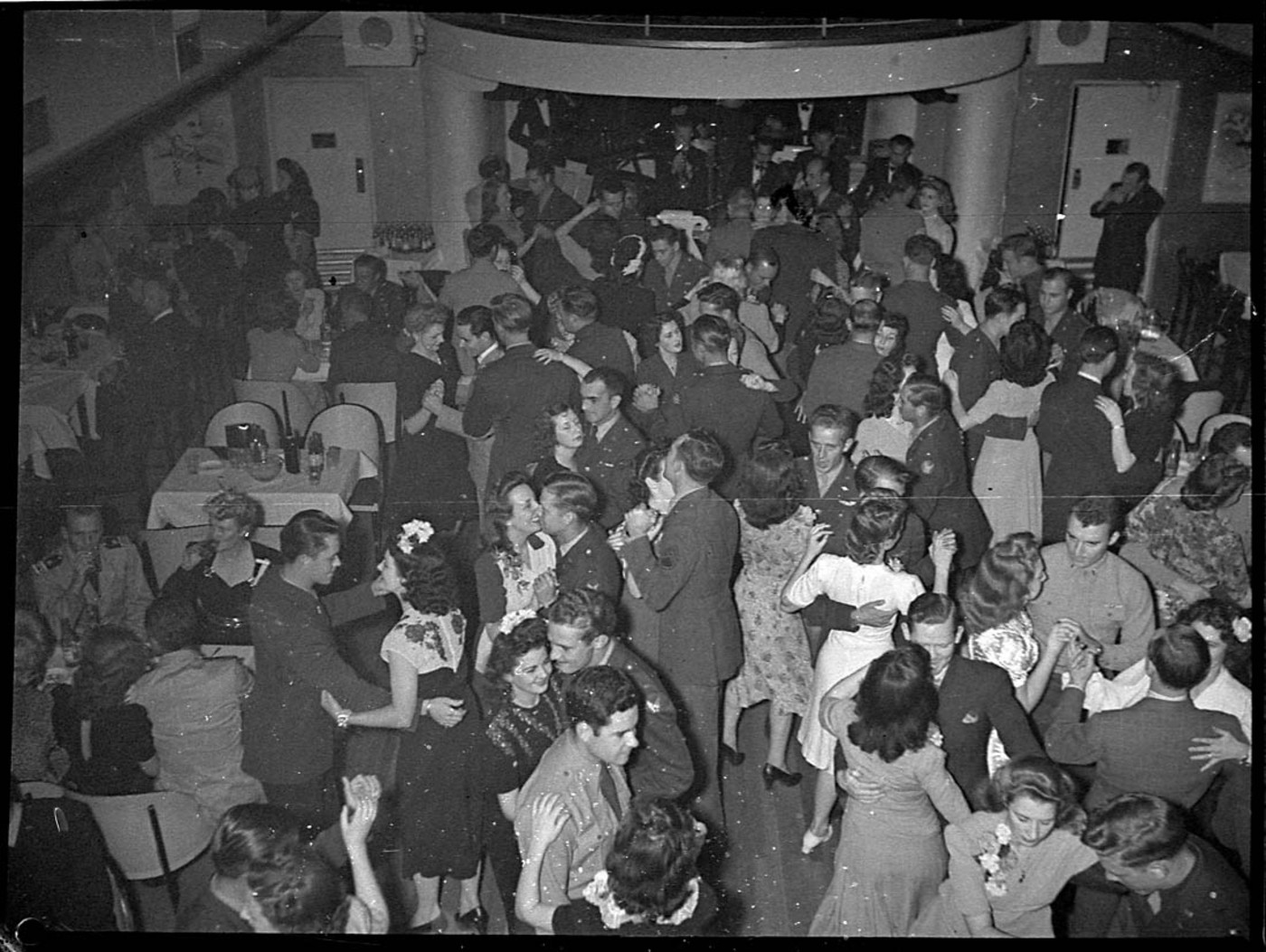

The outbreak of World War II, and in particular the entry of America into the fighting in late 1941, planted the seeds for the development of the Kings Cross scene that Sydney is more familiar with today. From early 1942 thousands of US servicemen and women arrived in Sydney as the build-up for the war in the Pacific against Japan got under way. Refugees, and evacuated troops, from countries in Asia already overrun added to the bustling scene. The Cross was a hub of activity due to its collection of cafés, restaurants and night clubs, as well as its proximity to the naval base at Garden Island where many of the troops and the various navies disembarked.

[media]A number of the older surviving mansions, as well as newer venues, were transformed into officers' clubs for the various armies, including Maramanah which was used by the US Navy, Bernly in Springfield Avenue and Cheverells (now replaced by the Gazebo Hotel) in Elizabeth Bay Road, both used as officers' clubs. [26] The Royal Australian Navy Women's Officers Club was also in Elizabeth Bay Road, while a combined Allied officers' residential club was opened in the mansion Kenneil opposite Cheverells. The cafeteria at the newly opened Woolworths in Darlinghurst was also handed over for use by the military to serve meals throughout the war, while the Roosevelt night club in Orwell Street, operated by promoter Sammy Lee, became a notorious late night venue for American officers. The Roosevelt, later managed by Abe Saffron, lasted until the end of six o'clock closing in 1955, after which it was leased to radio station 2KY for conversion to radio studios. [27]

Across Orwell Lane from the Roosevelt Club was the Minerva Theatre, opened in 1939. The Art Deco building was designed by Bruce Dellit, Guy Crick, Bruce Furse and Dudley Ward, with sculptures and the facade (never completed) by Rayner Hoff, who had collaborated with Dellit on the Anzac War Memorial in Hyde Park. The Theatre was one of two planned by David N Martin, managing director of the Minerva Centre Ltd which he established to develop the site. The second theatre, to be known as the Paradise, was proposed for Macleay Street. The Minerva opened as a live theatre on 18 May 1939. The Paradise was planned as a venue for movies, with a stage large enough for opera, ballet and musical productions, with a roof garden and cabaret shows; however it was never built. In 1950 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer took over the Minerva and converted it to a cinema (although it had played a week of movies in 1939). In 1969 it was returned to live theatre by Harry M Miller who used the venue for the musical Hair which ran as a sell-out for two years. Through the 1970s the building was used for movies as well as live shows before closing in 1979, and then re-opening as a food market. In the early 1980s, Kennedy-Miller productions took over the building, using it as offices and for film and television production. [28]

In June 1978 a protest march, commemorating the outcomes of the raid on the Stonewall nightclub in New York in 1969, ended in Kings Cross with 53 arrests. Protesting against police harassment of gay and lesbians, the marchers had made for Kings Cross after being dispersed by police from gathering in Hyde Park. At the Cross, the protesters, joined by a gathering crowd of supporters and onlookers, fought the police in a riot of flying garbage bins, bottles and cans. A full-scale riot marked the beginnings of Sydney's annual Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Parade.

Getting there

Despite its proximity to the city, Kings Cross has endured its fair share of troubles in regards to access. While William Street provided a direct route to the city and beyond to the east, in bad weather the steep slope proved difficult for horse drawn vehicles and carts, often making the long detour via Oxford Street necessary.

From the 1860s horse-drawn omnibuses ran along William Street, up the hill to Darlinghurst and on to Vaucluse and Potts Point, although a scattered population initially made it an irregular service. However by 1890 the patronage had increased to allow for 29 horse buses making 630 round trips per day between King Street in the city and Victoria Street, carrying an average of 8,820 people daily. [29] In 1894 a cable tram service was introduced to negotiate the steep grade of William Street, operating until at least 1901 in tandem with the remaining horse buses. This was upgraded to an electric system in 1905. [30] The same year Sydney's first government-operated steam bus route was trialled from Potts Point to Darlinghurst, to serve as a feeder service for the tram route, although this was abandoned by mid-1906. [31] Although the steam bus failed, private motor buses began to compete with the trams in the years following the end of World War I.

By the 1930s the service through Kings Cross was the busiest on the Sydney system, with trams running as close as one minute apart during weekdays. The trams were joined by Sydney's first trolley bus service in 1934; it ran from Liverpool Street in the city to Potts Point via Kings Cross. By the mid-1930s, trams, trolley buses and government-run motor buses all operated along William Street and through the Cross, helping to make the William Street, Darlinghurst Road and Victoria Road junction into one of Sydney's worst bottlenecks.

During the 1950s, patronage on the Watsons Bay tram line that serviced Kings Cross began to fall as more private cars came onto the road and government bus services began to increase. Pressure to close tramlines across the network had been building since the early 1950s and in January 1960 the closure of the line through the Cross was announced. Despite protests, the last tram ran through Kings Cross in the early morning of Sunday 10 July 1960. [32]

With trams withdrawn from service, calls intensified for the construction of an Eastern Suburbs Railway to serve Kings Cross and beyond. A plan for a railway to Sydney's eastern suburbs had been mooted since the 1870s and seriously on the drawing board since the building of the city circle line in the 1920s, but it was not until 1947 that work actually began. Although in that year an Act was passed authorising the completion of an Eastern Suburbs line (originally intended to go to Bondi Beach with extensions to Moore Park and Coogee) work proceeded in a stop-start manner through the 1950s and 1960s, until 1967 when work restarted. The line was officially opened, including the Kings Cross station, on 23 June 1979. [33]

Another long-planned piece of transport infrastructure to go through the Cross was a road tunnel to ease the notorious traffic congestion there. As early as 1939 plans were being made for the construction of a tunnel to take traffic under Kings Cross from Dowling Street to Roslyn Gardens. [34] War-time restrictions and lack of funds meant that although the plan was approved and property resumptions were mooted, work did not begin until the late 1960s. In February 1969 the project was officially started and 118 properties along the route were resumed, with approximately 600 residents affected. [35] Work on the project began in June 1973 with bulk excavation of the sandstone for the cut-and-cover tunnel. Although some delays were encountered when old tram tracks were uncovered in William Street, the new tunnel was officially opened by the Premier, TL (Tom) Lewis, on 15 December 1975. [36] The space above the tunnel was redeveloped and multistorey tower blocks and apartments were constructed.

Bright lights, dark corners

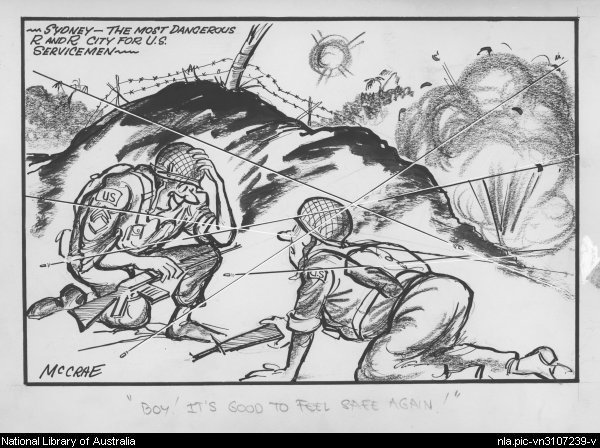

By the time Hair was released, the Kings Cross scene was changing. Since the influx of foreign armed forces in World War II, an increasing number of bars and clubs had appeared to cater to the scene. Soldiers and sailors on leave from battlefronts were often keen for a good time before returning to the war. With the Korean War and the Vietnam War following close behind World War II, the Cross continued as the place of choice for troops heading off or in Sydney on Rest & Recreation leave.

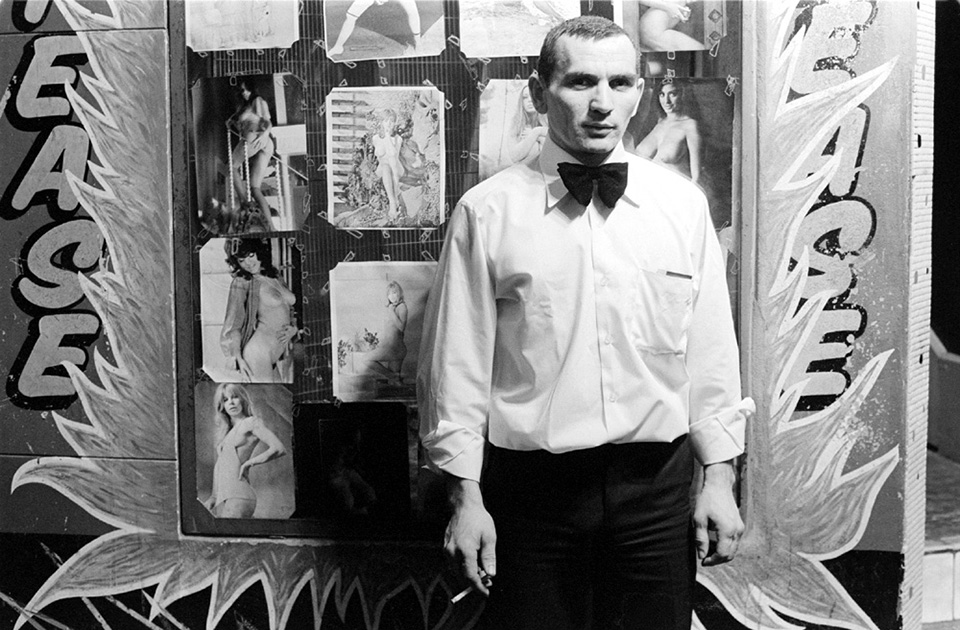

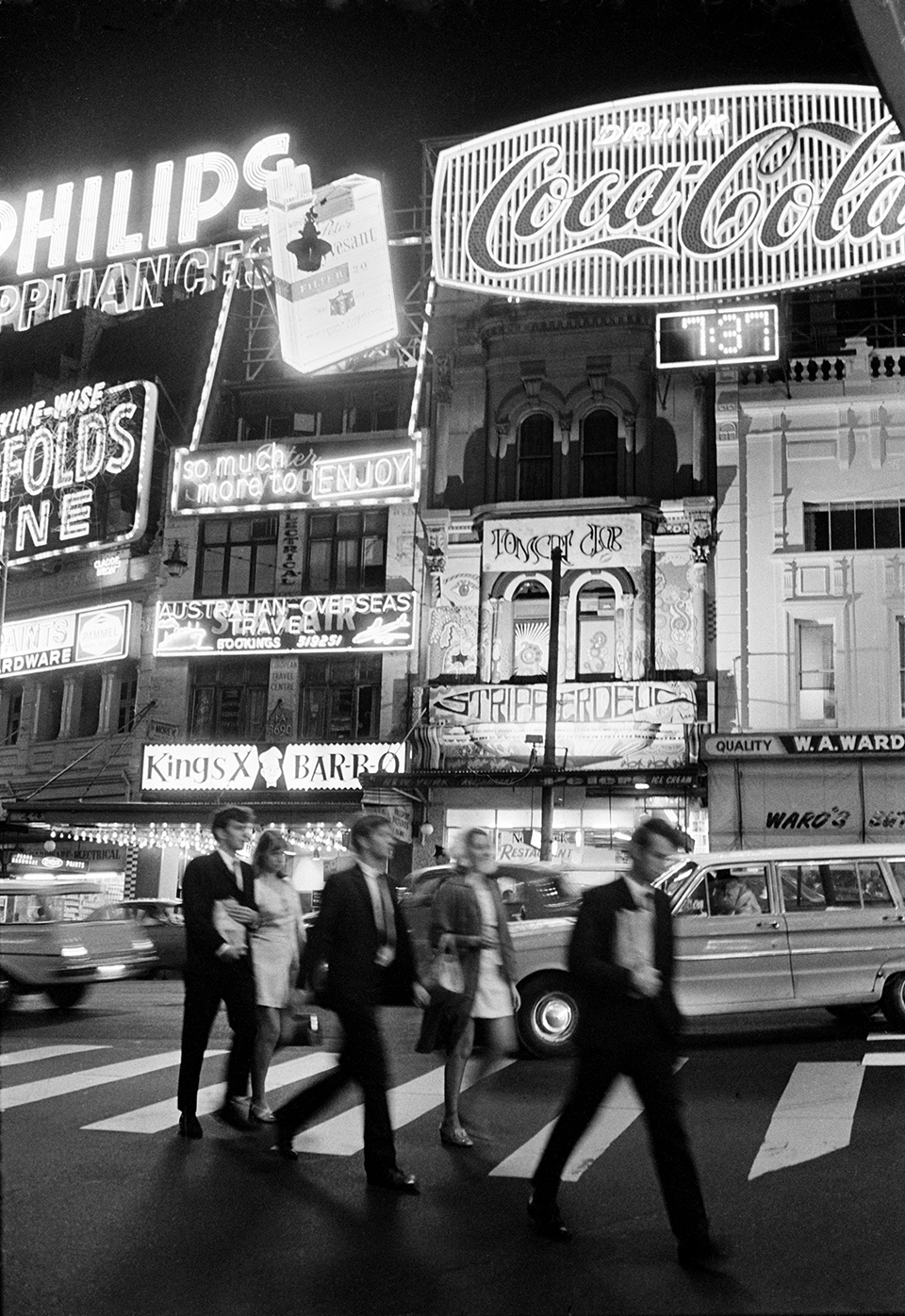

[media]From the later 1950s, the Kings Cross area had been increasingly associated with nightclubs and a growing number of topless bars and strip joints, with Darlinghurst Road taking on the moniker of 'the Strip'. [37] The Roosevelt nightclub had introduced topless showgirls in the early 1950s, and in 1959 the Staccato Club in Orwell Street opened as the first strip joint in Australia. As 'the Strip' developed, neon signs came to dominate the advertising landscape. William Street became one of the brightest streets in the country, while the Cross itself, particularly at the Victoria Street and Darlinghurst Road junction, was ablaze with reds, blues and greens advertising everything from the strip clubs to cigarettes, Dunlop tyres to Coca-Cola. The Coca-Cola sign that still dominates the top of the cross remains as one of the last survivors.

[media]The Vietnam War cemented the area's reputation as Australia's vice centre, as thousands of American servicemen came to the Cross while on leave from the war. By 1972, 280,000 US servicemen had visited Sydney on leave, and as had occurred during World War II, a majority were drawn to the Kings Cross bars and clubs. Clubs, such as the Pink Pussycat, the Pink Panther, the Kit Kat club, Les Girls (with its all-male revue) at the Carousel Club, the Venus Room, the Fox-Hole, the Claremont-Flamingo and Livio's, among others, jostled for business, offering everything from international entertainers to cabaret to strip shows and dancing girls. The Whisky a Go Go claimed to be the biggest night spot in the southern hemisphere with two floors of bars, bands and dancing girls. [38]

By the mid-1970s however, the glamour had largely been lost. Battles with developers over the redevelopment of Victoria Street in 1973 and 1974 turned attention onto the underworld element of the area, particularly after the disappearance of local identity, newspaper editor and anti-development campaigner Juanita Nielsen. Nielsen had advocated against the demolition of the Victoria Street terraces and the eviction of their residents in her newspaper, Now. Green Bans put in place by the Builders Labourers Federation, abductions of some of the protesters and violent clashes between protesters and development company security guards created a highly charged and volatile environment. On 4 July 1975 Nielsen disappeared, after keeping an appointment at the Carousel Club to discuss advertising in her newspaper. Her body has never been found. [39]

The area's reputation struggled to recover and was further tarnished with a series of Royal Commissions and enquiries into police corruption and links to organised crime through the 1980s and 1990s, culminating in the Wood Royal Commission in 1994–97.

Alongside the red light scene, Kings Cross also evolved as one of Sydney's main live music destinations. In the early 1960s, the former Kings Cross Theatre was transformed by music promoter John Harrigan into Surf City. At first the club attracted surf bands, a new craze in teenage music, but soon was a venue for rock and roll. Bands such as Billy Thorpe and the Aztecs, The Easybeats, Ray Brown and the Whispers or The Missing Links were regulars at the club. Crowds of up to 5,000 people crammed into the old theatre to dance to the new beat. Like so many things in the Cross, Surf City burnt brightly but not for long, closing in the mid-1960s to make way for the Kings Cross railway. It did however re-establish the Cross as a live music scene which continues into the present at venues such as the Kings Cross Hotel, diagonally opposite the old Surf City site.

Literary Kings Cross

The combination of the Cross's bohemian past, its sleazy underworld reputation and its place in Sydney's imagination, has fed a vast collection of novels, poems, writings, musings, songs and movies based in or around its streets. While some later novels, such as Patrick White's Voss, have been set in the area during the nineteenth century, it was in the 1920s that writers living in the area began writing about their home and times. Kenneth Slessor, Dulcie Deamer and Jack Lindsay all wrote of their time in the district in the 1920s and 1930s. Slessor's Darlinghurst Nights (1932) collected a series of his poems about the district and people in it, from the sophisticated to the marginalised. Robin Eakin (Dalton) captured the fading bohemia of the 1930s and 1940s in her memoir Aunts up the Cross (1965), while Dymphna Cusack and Florence James evoked the excitement and danger of the wartime Cross in Come in Spinner (1951).

HC Brewster's Kings Cross Calling (1952), complete with Rosaleen Norton's cover art, affectionately examines the Cross from the 1930s and through the rapid changes of the war years, commenting on the increasingly international population thrown into the area by world conflicts. In 1957 Nino Culotta (John Patrick O'Grady) was the 'newly arrived Italian migrant' dropped unsuspectingly in the middle of Kings Bloody Cross, eating at the Hasty Tasty in They 're a Weird Mob, which captured the postwar migration boom to the area. By 1963 'the Strip' was also attracting attention. James Holledge penned Inside Kings Cross (1963) trading on the growing notoriety of the strip clubs and bars. There are enough literary references to sustain walking tours of the sites and to publish a book about them, Mandy Sayer and Louis Nowra's In the gutter looking at the stars (2000).

The 'I was involved in the criminal underclass' memoir has also had plenty of traction in the Cross. The fascination with crime and sleaze in writing about the area has dominated more recent works such as Jimmy Thompson's Snitch: Crooked Cops and Kings Cross Crims (2010), while a number of biographies have been written about Abe Saffron and his Kings Cross years. Billy Thorpe's Sex and thugs and rock 'n' roll: A year in Kings Cross 1963–1964 (1996) recall the heady days of the Surf City club and the rise of the Aztecs.

In song, the Cross has also held a fascination. In 1963 Frankie Davidson asked 'Have you ever been to see Kings Cross?'; later Paul Kelly told us in 'From St Kilda to Kings Cross' was 13 hours on a bus, and Cold Chisel directed us to hot coffee and brown toast in 'Breakfast at Sweethearts' or a hard night out in 'Metho Blues'. The Angels' 'Shadow Boxer' was inspired by scenes in the Cross while Redgum's 'Working Girls' has the Kings Cross girls bathed in a neon glow. Movies like Two Hands (1999) and Dirty Deeds (2002) looked at the local underworld, as did the television series Underbelly 3: The Golden Mile. The disappearance of Juanita Nielsen inspired the films The Killing of Angel Street (1981) and Heatwave (1982), while Winter of our Dreams (1981) had Judy Davis as a Kings Cross prostitute caught up in a murder.

The changing Cross

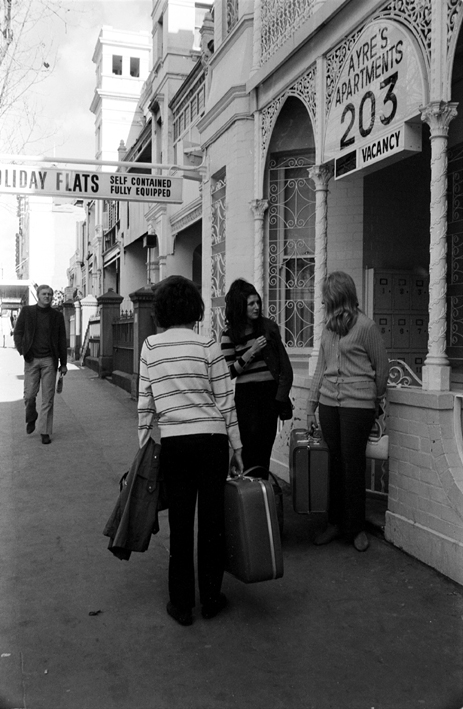

Kings Cross is [media]possibly the only suburb in Sydney that nearly everyone has visited and that everyone has an opinion on. It has worked as its own best publicist and its own worst enemy, with as many tales of bohemian freedom as there are of back street deals and random violence. Its place on the ridge overlooking the city has always set it apart from the rest of town, an 'exclusive' address from the start. It has often led Sydney in coming trends, from coffee shops and delicatessens to apartment living. It is forever changing its residents and its appeal. As Wesley Stacey and Rennie Ellis said in 1971:

The old timers will tell you the Cross has had it. It's not like it used to be, they'll say. And they're right of course. It's not, for Kings Cross exists in a permanent state of mutation, and herein lies its very existence – its adaptability to change, its readiness to accept and absorb a new generation with new ideas yet still retain its unique sangfroid. [40]

This is the one constant of the Cross; people always think it was better when they were there.

Notes

[1] HC Brewster, Kings Cross Calling, Liberty Press, Sydney, 1954, p 5

[2] M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 8

[3] 'City Council Arrangements', Sydney Morning Herald, 4 June 1897, p 5

[4] Sydney Morning Herald, 15 Nov 1906, Funerals, p 12

[5] F MacDonnell, Before Kings Cross, Thomas Nelson, Sydney, 1967, p 12

[6] Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser, 12 February 1833, p 2

[7] Sydney Monitor and Commercial Advertiser, 1 October 1841, p 4

[8] 'Rambles in the Suburbs', Sydney Mail, 14 July 1860

[9] M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 53

[10] M Kelly, Faces in the Street: William Street Sydney 1916, DOAK Press, Sydney, 1982, p 57

[11] Sands Sydney Country and Commercial Directory: 1890, 1905 and 1915

[12] Richard Cardew, 'Flats in Sydney: the thirty per cent solution?' in J Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney: Studies in Urban & Social History, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1980, p 77

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 October 1930, p 10

[14] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September 1939, p 11

[15] HC Brewster, Kings Cross Calling, Liberty Press, Sydney, 1954, p 100

[16] Welcome: the Official Bulletin of the All Nations Club

[17] Memories of Kings Cross 1936–1946, Kings Cross Community Aid and Information Service, 1981, p 97

[18] Memories of Kings Cross 1936–1946, Kings Cross Community Aid and Information Service, 1981, p 95

[19] Scott Carlin, 'Kings Cross; Bohemian life in Sydney', Historic Houses Trust website, http://www.hht.net.au/discover/highlights/insites/kings_cross_bohemian_life_in_sydney, viewed 12 December 2012

[20] Chris Cunneen, 'Magnus, Walter (1903–1954), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 15, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, available online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/magnus-walter-11035

[21] Home, 1 March 1923, p 32

[22] Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September 1939, p 11

[23] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1935, p 4

[24] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 March 1935, p 6

[25] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1940, p 7; P Spearritt, Sydney's Century: A History, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1999, p 78

[26] HC Brewster, Kings Cross Calling, Liberty Press, Sydney, 1954, p 87

[27] D McNab, The Usual Suspect: The Life of Abe Saffron, Macmillan, Sydney, 2005, p 63

[28] JS Clark, Art Deco Cinemas Series 1: The Minerva, Australian Theatre Historical Society, Sydney, 1993, pp 5–22

[29] David Keenan, The Watson Bay Line of the Sydney Tramway System Cable & Electric 1894–1960, Transit Press, Sydney, 1990, p 5

[30] David Keenan, The Watson Bay Line of the Sydney Tramway System Cable & Electric 1894–1960, Transit Press, Sydney, 1990, p 28

[31] G Travers, From City to Suburb...a fifty year journey: The story of NSW Government Buses, Sydney Tramway Museum, Sydney, 1982, p 1

[32] David Keenan, The Watson Bay Line of the Sydney Tramway System Cable & Electric 1894–1960, Transit Press, Sydney, 1990, p 78

[33] The Story of the Eastern Suburbs Railway, Public Transport Commission of NSW, Sydney, 1979

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1939, p 10; 12 February 1941, p 13

[35] Main Roads: Journal of the Department of Main Roads, NSW, September 1972, p 20

[36] Main Roads: Journal of the Department of Main Roads, NSW, December 1975, p 34

[37] J Holledge, Inside Kings Cross, Horwitz Publications, Sydney, 1963, p 8

[38] R Ellis and W Stacey, Kings Cross Sydney, Thomas Nelson, Sydney, 1971, p 64

[39] R Morris, 'Nielsen, Juanita Joan (1937–1975)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 15, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 479–80, available online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nielsen-juanita-joan-11241/text20047, viewed 12 December 2011

[40] R Ellis and W Stacey, Kings Cross Sydney, Thomas Nelson, Sydney, 1971, p 6

.