The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Maiden, Joseph

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Maiden, Joseph

Joseph Henry Maiden was [media]born in London in 1859 and sailed for Australia in 1880, where he lived for the remainder of his life. He was an ardent Australian nationalist, and like many immigrants of this time, remained proud of his British heritage. His sweetheart, Eliza Jane Hammond, followed him to Australia in 1883. They married in Kew the day after she made port in Melbourne, and together in Sydney they raised five children. [1] During the first phase of his career Maiden presided over the Technological Museum of Sydney from 1882 to 1896. In the second phase, he was the director of the Sydney Botanic Gardens from 1896 to 1924. There he managed a whole complex of parks including the Domain, Centennial Park and the Governor's residences, a state nursery at Campbelltown and a scientific institution, the National Herbarium of New South Wales, devoted to botany. A short time after his retirement, he died at his home in Turramurra in 1925.

During his long and prolific career, Joseph Maiden mastered many aspects of scientific work. He was a botanist first, but also a curator, a collector, a traveller, a horticulturalist and a plant scientist. Moreover, in performing each of these roles, he never forgot his strong commitment to education. He desired higher levels of education for Australians about botanical matters and felt this was of crucial importance to life in Sydney. Maiden took a broad view of education and certainly did not consider it to be confined to the classroom. Instead, his approach was to integrate education into all aspects of his professional life. He pursued education through three different modes: collections and their exhibitions, public lecture series, and his writings and publications.

Collections

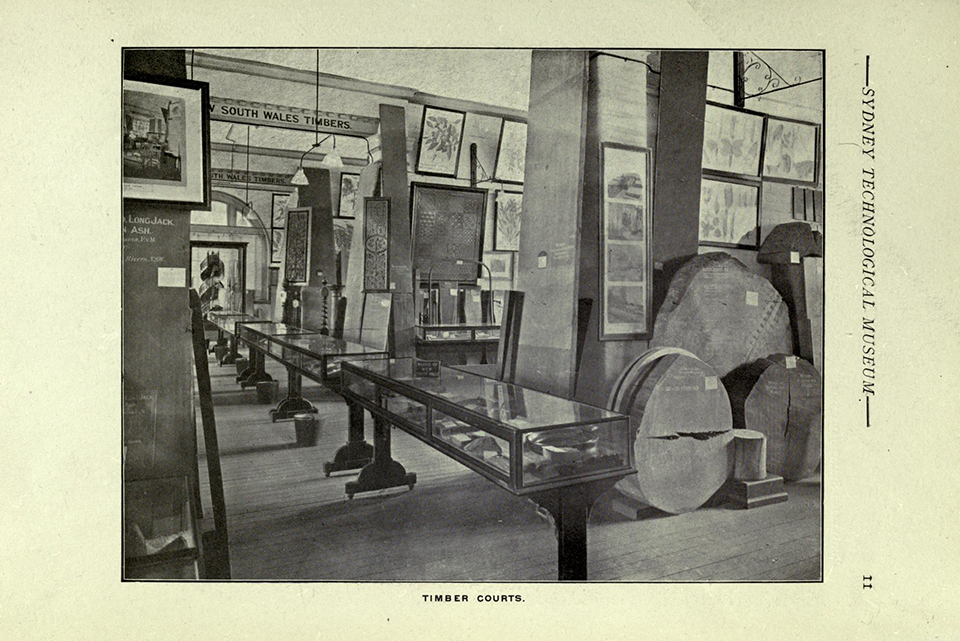

Apart [media]from the first year in Sydney, all of Maiden's professional roles included curatorship of collections. While the content of the collections was vastly different between the museum and the botanic gardens, Maiden's attitude to exhibitions was always didactic. This was a time when 'learning by looking' drove the exhibition policies at museums and botanic gardens.

Maiden was the second curator of the Technological Museum and was responsible for collection and display of the museum objects. Visitors to the museum were presented with 'narratives of progress' revolving around botany, geology and zoology, particularly of Australia. [2] By taking a raw product and demonstrating how it could be made useful, the exhibits focused on ideas of progressive transformation. This gave the exhibition a national focus and brought technology and innovation to the gaze of the public.

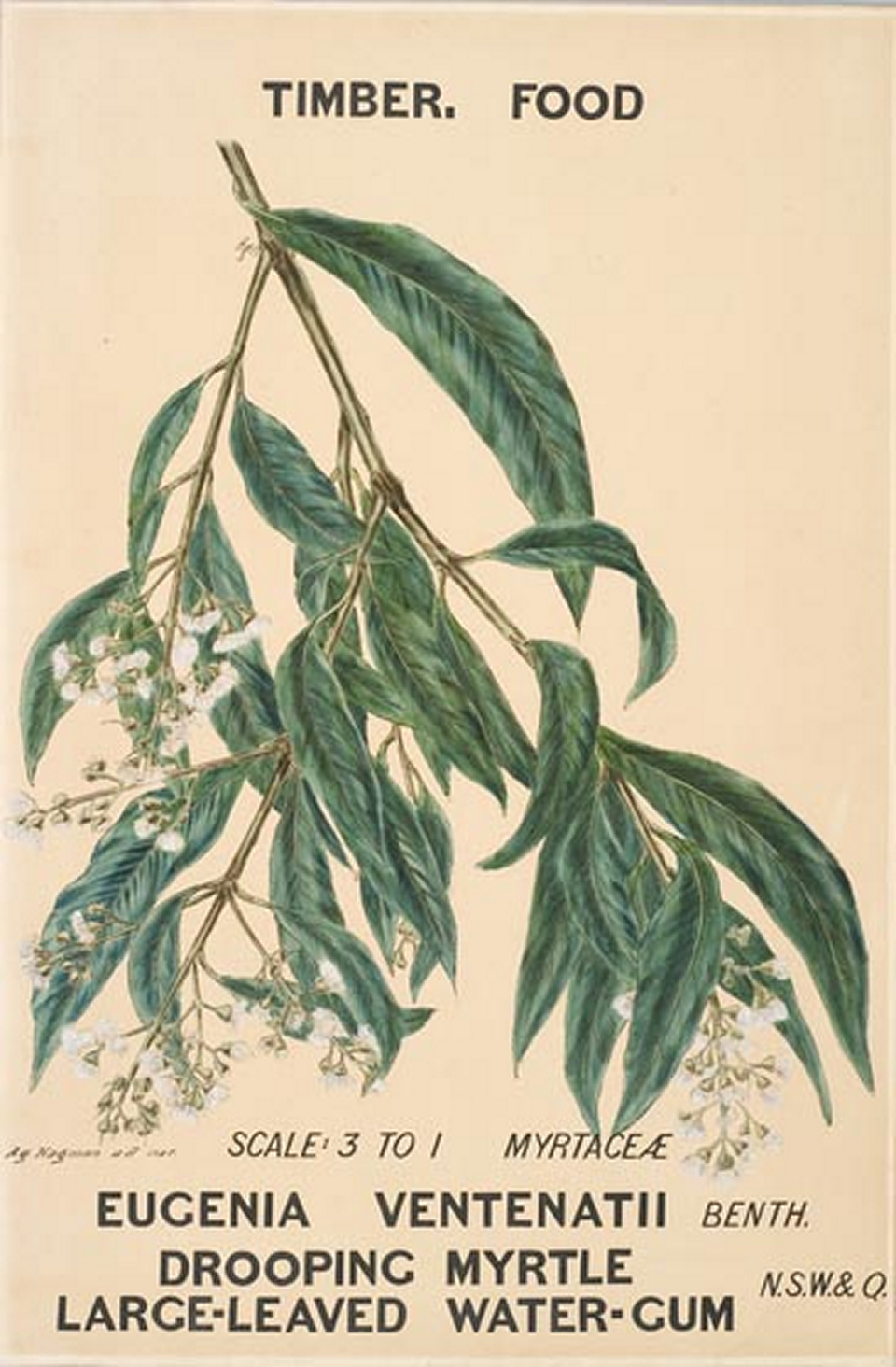

One [media]example of this progressive narrative was built into the displays relating to the Sydney eucalypt E. pilularis. Framed Herbarium specimens hanging on the walls of the museum gave visitors a feel for the plant in a natural state, while also demonstrating where the plant belonged within the nomenclatural system of Linnaeus. [3] A timber sample of the tree showed the texture and grain. [4] Supplementing the timber were tools like pit saws, as well as axes used in the forestry industry. [5] Accompanying these technologies were photographs of logging practices and particularly transport: bullock trains, log chutes [media]and light gauge rail. [6] Photography was a technological marvel in its own right and the inclusion of photographic images in displays demonstrates Maiden's innovative approach. In his publications about E. pilularis, Maiden lists the uses of this hardwood timber as including house- and ship-building, bridge planking, wood paving blocks and as sides and head-blocks in railway wagons. [7] Any of these uses could have been sampled and displayed to show how the raw product progressed once it was in the hands of men.

At the Sydney Botanic Gardens, the [media]collections were created in multiple sites: a living collection of plants in the park, and in the botanical museum and herbarium, a collection of dried plant specimens. These specimens are of national importance to botany in Australia. For example, in 1905, Maiden secured a set of specimens created by Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on their voyage to Australia on the Endeavour in 1770. The park, and the museum in particular, afforded Maiden the opportunity to direct public interaction with both local and international plants.

The [media]botanical museum was originally developed under Maiden's predecessor Charles Moore. The museum displayed the products and knowledges of indigenous peoples, lands and communities all over the world. As in the Technological Museum, themes focused on an imagined progress from indigenous cultures to those of colonising settlers. [8] The displays were suggestive of ways that Australians could adapt and translate native practices of plant use to local circumstances.

Each item displayed was described in the catalogue for the way it was used in its country of origin. For example, Item 551, fruits of Barringtonia sp from India.

The seeds of the Barringtonia have narcotic properties, and are used by the natives of India and the South Sea Islands to inebriate fish, in order to facilitate their capture. [9]

In this way, the museum displayed the ethnographic curiosities of 'native' cultures, but at the same time informed visitors about plant use. Under Moore's charge, the museum had mostly inventoried exotic plants and plant products, whereas in the new and enlarged museum opened in 1899, with purpose-built rooms and display cabinets, Maiden made a greater effort to include and explain Australian botany and its products. [10] In this, for example, he was able to add knowledge about inebriative qualities of Acacia facata and Cupania pseudorhus used by Aboriginal peoples in river fishing.

The [media]other important didactic space in the Sydney Botanic Gardens was the living collection. Botanic gardens throughout the world were differentiated from other city parks through the expectation that a visit there would be educational. Each and every plant in the gardens was labelled with its correct scientific name, country of origin and common name. The map of the botanic gardens at this time shows the various sections of the garden – upper, middle and lower. These were arranged in such a way that visitors could see plants collected together through their country of origin or as was the case in the middle garden, arranged under the 'natural orders' of taxonomic classification.

Maiden remodelled the middle gardens in 1896 so that they would include more Australian plants. One section was filled with dicotyledonous plants; those flowering plants that have seeds with two embryonic leaves. He was pleased to report that 'this arrangement ground is of the most directly educational value of any portion of the Gardens.' [11] He arranged pharmacopoeia gardens for medicinal plants, enlisting the cooperation of the Pharmaceutical Society of New South Wales. Additionally monocotyledonous gardens, which included indigenous and non-indigenous grass species, were part of this educational work in the middle gardens. He also kept experimental plots for these grasses that tested the viability of different plants in Sydney conditions, at the same time as demonstrating their value to a curious public.

Lectures

It was Maiden's [media]teaching experience in London that secured him his first employment in Sydney in 1880. His biographer Lionel Gilbert speculates that Maiden held two jobs in his first year in Australia. The first was an unconfirmed role as a tutor for the Macarthur-Onslow children at Camden Park. Although largely known as the centre for the introduction of merino sheep into Australia, [12] Camden Park also had a longstanding and thriving nursery and seed exchange business operating as part of its commercial ventures. [13] There, he came into contact with the aged William Macarthur which was to later prove important in his work on the Eucalyptus species. [14] He held a second position delivering a weekly lecture on science at the Technical or Working Men's College in Sydney. This course was called 'Science made easy' and was a kit form lecture series that Maiden had brought with him from England.

The college which employed Maiden had been established by Sydney's first mechanics' institute, the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, itself an important venue for public lectures. Philip Candy argues in relation to mechanics' institutes that the public lecture 'served as a major vehicle for enlightenment and entertainment.' [15] In an effort to fulfil these aims, Maiden nurtured public lecture series at both the museum and the botanic gardens. Over his career he lectured on many varied topics as he spoke to working men's groups, technical guilds and other interested parties. In 1884 he undertook a lecture program delivered on the museum premises each Wednesday afternoon at 4.15 pm. Each lecture used a selection of objects to demonstrate the economic potential of a range of natural specimens and museum items. The lectures ranged across the three broad themes of the museum; botany, geology and zoology. [16]

In other [media]contexts he talked about his travels into the bush and at other times he provided the latest in scientific classification data for his audience. When the technology was available he liked to illustrate his lectures with lantern slides. This allowed him to show specific trees or plants, as well as their natural settings from his trips through the Australian bush. He addressed students at Sydney Girls' High School on the benefits of Empire [17] and plant foods used by Aborigines. [18] He spoke about national symbols of other nations and the Australian need for a floral emblem to the girls of the Clergy Daughters' School. He helped to promote wattle in this way as part of the Wattle League of New South Wales. Over the course of his career he developed a diverse repertoire of lecture subjects while at the same time tending a public profile as a man of useful science.

Publications

In 1889 Maiden [media]published his first book, The Useful Native Plants of Australia. [19] This book established a mode of address that was to be found in all of his subsequent publications. It dealt with the practical applications of plants and plant products to settler life. Like all his works it was purposefully written for both popular and specialist audiences. Writing the preface to The Forest Flora of New South Wales over 20 years later, Maiden summed up:

It is hoped that this work will support all classes of citizens, not only those in pursuit of forestry and the various industries connected with timber, but all gardeners and amateurs who plant trees; also botanists, and those who are content with the less pleasing designation of lovers of flowers and of our vegetation. [20]

His aim was to produce work that maintained scientific rigour, but that was written in such a way as to reach out across the Australian community. Many of his works operated as ready reckoners, designed so that Australians could clip samples from living trees, shrubs or flowers and then find the corresponding plant in one of Maiden's books. Once identified, each entry included information about habitat and range, but also about how a particular plant was used, or could be used in settler society. His larger works, such as the Critical Revision of Genus Eucalyptus, were originally produced as smaller parts, which made them affordable to a broader audience. Maiden also responded to the needs of particular communities in producing smaller publications, as with Wattles and Wattlebarks and A Manual of Grasses of New South Wales.

In [media]addition to these major works, Maiden also contributed to the local press. Articles covered debates that intersected with his botanical interests. He published articles about parks and advocated the introduction of street trees into Sydney suburbs. He was also a regular contributor of letters to the editor where his authority was added to numerous debates about plants, parks and urban aesthetics. The Lone Hand, a popular patriotic magazine, carried a discussion of the botany of the wattle along with his views on national sentiment. He published several series of articles in specialist magazines, for example the Public Service Journal carried monthly articles over a two-year period expressly to educate a Sydney audience about flora in the various parks and gardens under his care. He was a prolific author for Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales , writing about a vast array of subjects from prickly pear to forestry for an audience beyond the city boundaries.

An illustration of this style of publication is found in two articles published by the Sydney Morning Herald called 'A Plea: Our Brush Forests'. [21] Maiden was arguing for the conservation of New South Wales rainforests as an alternative to their wholesale destruction and replacement with agriculture and grazing land. He used a descriptive style to invoke emotional response. In discussing the animals in these ecosystems, he said:

As we approach the brush we hear the sweet note of the bell-bird, the clod-hopping noise of the wallaby, in a violent hurry; the clumsy unquiet flapping of the wonga pigeon inviting the attention of the sportsman. [22]

Maiden was drawing on his experience of travelling through these rainforests to create empathy for Australian nature for his urbane Sydney readership. He argued for alternative ways to utilise forest resources for harvesting of timber, bark and ornamental flora, as well as suggesting that such forests had an intrinsic aesthetic value.

Maiden's [media]greatest educational skill was his ability to draw on multiple resources in his quest to inform. He masterfully translated complex scientific information so that it was more accessible to a general audience. In doing this he didn't compromise his scientific integrity, but instead looked for opportunities to bring knowledge about plants, plant material and plant information into the public realm. This applied to the collections under his care, as well as information produced in the laboratories and herbarium, usually sites held away from the public gaze. In doing so, Maiden also developed a profile as a public intellectual, a role that then allowed him to comment on other issues of concern to the Sydney metropolis.

Maiden's [media]legacy is the continuing importance of the Technological Museum – now the Powerhouse Museum – and the Royal Botanic Gardens in Sydney. Each place was shaped by his early championing of collections that could be usefully applied to life in Sydney. Both are iconic Sydney institutions, continuing to provide venues for pleasure, science, entertainment and education – just as they did when Maiden was their master in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

References

Alan Atkinson, Camden, 2nd ed, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne, Victoria, 2008

British Association for the Advancement of Science, Handbook of New South Wales, Edward Lee & Co, Sydney, 1914

Philip Candy, 'The Light of the Heaven Itself: The Contribution of the Institutes to Australia's Cultural History', in Philip C Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Art in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide, 1994, pp 1–28

Graeme Davison, Kimberley Webber and Powerhouse Museum, Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and Its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing in association with University of New South Wales Press, Haymarket NSW, 2005

Sarah Franklin, 'Colony', in Dolly Mixtures: The Remaking of Genealogy, Duke University Press, Durham North Carolina USA, 2007, pp 118–57

Catherine Freyne, 'Spectacle and the City: Sydney's Garden Palace', radio documentary, ABC Radio National, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/hindsight/stories/2008/2326489.htm, accessed 21 September 2010

Lionel Gilbert, 'Joseph Henry Maiden', in Richard Aitken and Michael Looker (eds), The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens, Oxford University Press in association with the Australian Garden Society, Melbourne, 2002, pp 394–95

Lionel Gilbert, The Little Giant: The Life and Work of Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925, Kardoorair Press in association with Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 2001

AHS Lucas, 'Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925 (Memorial Series No 3)', The Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, vol 55, 1930, pp 355–70

Mark Lyons and CJ Pettigrew, 'Maiden, Joseph Henry (1859–1925)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 381–83

Notes

[1] Lionel Gilbert, The Little Giant: The Life and Work of Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925, Kardoorair Press in association with Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 2001; Lionel Gilbert, 'Joseph Henry Maiden', in Richard Aitken and Michael Looker (eds) The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens, Oxford University Press in association with the Australian Garden Society, Melbourne, 2002, Mark Lyons and CJ Pettigrew, 'Maiden, Joseph Henry (1859–1925) ' in Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986

[2] Richard White, 'Imagining: Representing Australia', Graeme Davison, Kimberley Webber and Powerhouse Museum (eds), Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and Its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing in association with University of New South Wales Press, Haymarket NSW, 2005, p 128; Graeme Davison quoted in Catherine Freyne, 'Spectacle and the City: Sydney's Garden Palace', radio documentary, ABC Radio National, http://www.abc.net.au/rn/hindsight/stories/2008/2326489.htm, accessed 21 September 2010

[3] Graeme Davison, Kimberley Webber, and Powerhouse Museum, Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and Its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing in association with University of New South Wales Press, Haymarket NSW, 2005, pp 128, 31, 33, 37

[4] Graeme Davison, Kimberley Webber, and Powerhouse Museum, Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and Its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing in association with University of New South Wales Press, Haymarket NSW, 2005

[5] Graeme Davison, Kimberley Webber, and Powerhouse Museum, Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and Its Precursors 1880–2005, Powerhouse Publishing in association with University of New South Wales Press, Haymarket NSW, 2005, p 87

[6] One example of this is a photograph of a timber bridge on the road to Macksville that showed a native stand of Blackbutt located next to logging transport and bridge of E. pilularis – a combination of nature versus technology and raw versus useful. This photograph was reproduced in British Association for the Advancement of Science, Handbook of New South Wales, Edward Lee & Co, Sydney, 1914

[7] Joseph Maiden, 'Part 1 No 1 Eucalyptus Pilularis (Smith)', in A Critical Revision of the Genus Eucalyptus, Government Printer, Sydney, 1903, p 29

[8] Charles Moore, 'Catalogue of the Botanical Museum, Sydney Botanic Gardens', Sydney Botanic Gardens, Sydney

[9] Sydney Botanic Gardens, 'Catalogue of the Botanical Museum', Sydney, 1883, in Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney Ephemera Collection, p 32

[10] Joseph Maiden, 'Report on Botanic Gardens and Domains for the Year 1903', New South Wales Legislative Assembly, 1905, p 18

[11] Joseph Maiden, 'Report on Botanic Gardens and Domains, &C For the Year 1896–7', Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 1897, p 2

[12] Colin Mills, 'The Case of the Missing Notebook', Australian Garden History, vol 18, no 1, 2006; Sarah Franklin, 'Colony', in Dolly Mixtures: The Remaking of Genealogy, Duke University Press, Durham North Carolina USA, 2007

[13] Lionel Gilbert, The Little Giant: The Life and Work of Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925, Kardoorair Press in association with Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 2001, pp 35–38, Alan Atkinson, Camden, 2nd edition, Australian Scholarly Publishing, North Melbourne Vic, 2008, p 39

[14] Lionel Gilbert points out that there are no official records that support the Maiden family's testimony that he was a tutor for the Macarthur-Onslows, but Gilbert is convincing that this was highly probable. AHS Lucas, 'Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925 (Memorial Series No 3)', The Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales, vol 55, 1930

[15] Philip Candy, 'The Light of the Heaven Itself: The Contribution of the Institutes to Australia's Cultural History', in Philip C Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Art in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide South Australia, 1994

[16] Lionel Gilbert, The Little Giant: The Life and Work of Joseph Henry Maiden 1859–1925, Kardoorair Press in association with Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, 2001

[17] Joseph Maiden, 'Acacia Burkittii, FVM Burkitt's Wattle', in The Forest Flora of New South Wales, William Applegate Gullick, Sydney, 1911

[18] Joseph Maiden, 'Some Plant-Foods of the Aborigines', Agricultural Gazette of New South Wales, vol 9, no 4, 1899

[19] Joseph Maiden, The Useful Native Plants of Australia (Including Tasmania), Compendium, Melbourne Victoria, 1889, reprinted 1975

[20] Joseph Maiden, 'Preface', in The Forest Flora of New South Wales vol 1, William Applegate Gullick, Sydney, 1903–04, p iv

[21] Joseph Maiden, 'A Plea: Our Brush Forests: I', Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 1908, Joseph Maiden, 'A Plea: Our Brush Forests : II', Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June 1908

[22] Joseph Maiden, 'A Plea: Our Brush Forests: I', Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 1908 p 8