The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Mitchell, David Scott

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Early years

David Scott Mitchell [media]was born on 19 March 1836 in the officers' quarters of the Sydney Hospital in Macquarie Street, not far from the site where the building housing his collections would later stand. He grew up at Cumberland Place and attended St Philip's Grammar School at Church Hill. Mitchell was the only son of Dr James Mitchell, a physician of Scottish origin, and Augusta Maria Frederick Scott, a member of a well-connected family with properties in the Hunter River region. He also had an older sister, Augusta Maria, and a younger one, Margaret.

Bachelor and gentleman

Mitchell was in the first intake of 24 undergraduates at the newly established University of Sydney in 1852. Despite being formally censured in 1854 for 'gross and wilful neglect to his studies', he went on to graduate as a Bachelor of Arts in 1856 and three years later as Master of Arts. He was admitted to the Bar in December 1858 but never practised the law or any other paid profession. During his twenties he had a carefree existence and a busy social life, living at home and indulging his interests in cricket, croquet, dancing and cards. Mitchell also belonged to the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts Debating Society, wrote poetry and performed in amateur dramatics.

In 1865, at the age of 29, he became engaged to Emily Manning, the daughter of Sir William Manning, a Supreme Court judge and Chancellor of the University of Sydney. At the time, it was deemed as a perfectly suitable match, yet the engagement only lasted a few months, and by 1869 Miss Manning was in London. For the rest of his life, the most significant female figure in Mitchell's life was to be his younger cousin, the feminist and pioneer Rose Scott.

Starting the collection

After his father died in 1869, Mitchell inherited extensive lands in the Hunter valley, including the coal-rich estates of Branxton, Cessnock and Rothbury. It was the income from these estates that enabled Mitchell to devote all of his time and energies to his 'magnificent obsession', the collecting of books. He began his collection with English literature, in particular Elizabethan drama and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century writers and poets. He was also interested in English cartoons and caricatures of the Georgian and early Victorian eras, including some rare examples of the collected works of Cruikshank, Hogarth and Gillray.

Mitchell also began acquiring works on Australian and Pacific history during the 1860s. In Sydney he was known to all the prominent booksellers, such as Dymocks and Angus & Robertson, and he was regularly found at market stalls, in bookshops and pawnshops, looking for oddities, rare pamphlets and manuscripts. He also had contacts with book dealers in England and Europe. Dealers visited him, bearing their wares. Scholars, journalists and writers like Banjo Paterson sought his advice on historical sources or the loan of a rare book.

From the 1880s, the bookseller George Robertson gave Mitchell the first right of refusal on any item of Australiana, and other booksellers would also go out of their way in search of rarities to court his business. In 1887 he acquired from Angus & Robertson a small library that included the First Fleet journals and various accounts of voyages of exploration. From this time until his death 20 years later, Mitchell became utterly absorbed and obsessed with collecting everything and anything of importance that related to the history of Australia and the surrounding region, and nothing was allowed to stand in his way when he located something he wanted.

Courted by the Public Library

[media]In 1895 Mitchell was introduced to Henry Charles Lennox Anderson, then Principal Librarian of the Public Library in Sydney. Anderson soon became a weekly visitor to Mitchell's home, bringing anything of interest to his attention, arranging purchases in London and generally acting as his agent and collecting-broker for antiquarian items. Around the turn of the century Anderson was buying about £2000 worth of Australiana from overseas each year on Mitchell's behalf.

In 1900 a Select Committee of the NSW Parliament was appointed to investigate Anderson's somewhat 'dubious' administration of the Public Library. [1] One of the matters before the Committee was a verbal agreement which took place between Mitchell and Anderson in October 1898, when Mitchell stated his intention to bequeath his collection to the Public Library on the condition that a new building be provided to house the collection separately, under the name of the Mitchell Library. Mitchell also provided an endowment of £70,000 to fund additions to his collection.

The struggle for a building

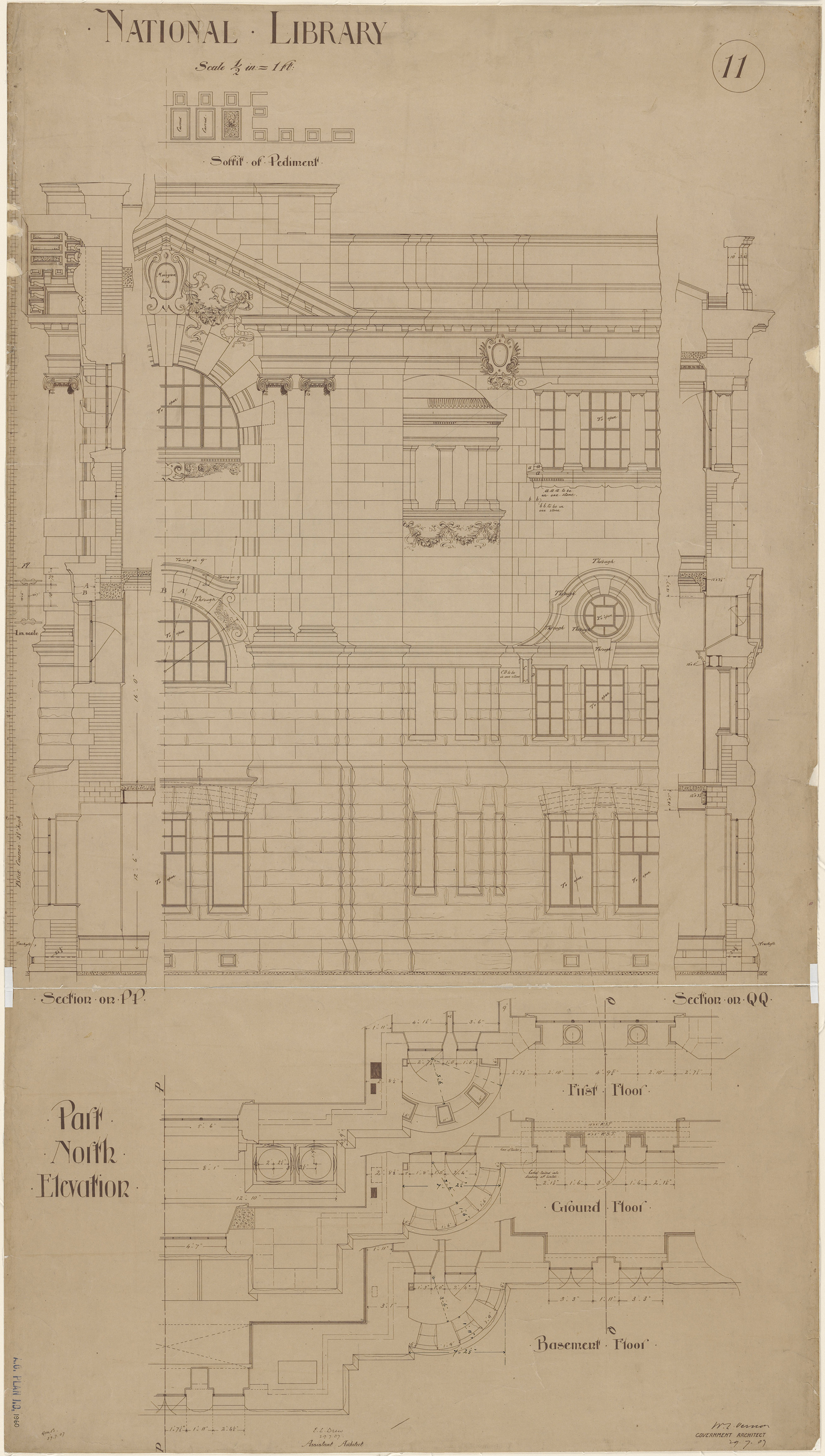

[media]The select committee supported the need for a new building, but it took another six years for construction to commence. By 1905, Mitchell was frail and ill and he demanded action from the Premier, JH Carruthers, threatening to donate his entire collection to the University of Sydney, or even sell it. The Premier referred the matter of a building immediately to the Parliamentary Standing Committee of Public Works, and engaged the Government Architect, Walter Liberty Vernon, and his office to begin sketching plans. Under Vernon, the office was responsible for such notable buildings in the city as the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Registrar-General's building and the Central Railway Station. A number of sites were considered for the location of the new library, including Hyde Park Barracks, Cook Park, and a site near the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The eventual site chosen was next to Parliament House, facing the Royal Botanic Gardens and the Domain.

Sydney opinion was divided on the choice of Macquarie Street. The Daily Telegraph suggested to its readers in 1905 that 'It is unquestionably a site of noble eminence'. [2] However, the Evening News felt that the site was not salubrious enough for a library, noting that

the approaches to the Domain possess the disadvantage of being frequented by few people in the evening, and those often not of a desirable class… [3]

JH Maiden, the Director of the Royal Botanic Gardens and self-appointed 'watchdog of the Domain', was also opposed to the 'nibbling away' of public lands and destruction of some greenery on the site. [4]

Others criticised the architectural plans drawn up by the Government Architect. In a letter to the Telegraph, one critic wanted a more indigenous design than the English-born Vernon had come up with:

As an Australian, I also claim that Australian architects should be invited to forward competitive designs for this important public building … a people's library should be designed by themselves. [5]

In the Evening News 'Gothic' suggested that the design would

serve admirably for an industrial exhibition, where a vulgar ostentation would have an advertising quality, but as a library where the peace of antiquity is supposed to rest undisturbed, it is singularly inappropriate. [6]

[media]Despite these criticisms of the site and the design, the foundation stone was laid by the Premier on 11 September 1906. The building contract was awarded to John and Archibald Howie, who had also worked on the Art Gallery, the old Public Library and a number of other public buildings in Sydney.

Mitchell's bequest

Mitchell himself approved of both the design and the site, but he never visited the magnificent library built in his name. He died of pernicious anaemia at the age of 71 on 24 July 1907. He was buried in the Church of England section at Rookwood Cemetery. On the day following his death, Premier Carruthers issued an extraordinary issue of the Government Gazette of New South Wales in commemoration of

The decease on the 24th instant of David Scott Mitchell Esquire, MA, an old and worthy colonist, and one of the greatest benefactors this State has known of recent years. A large hearted citizen, to whose memory is due an everlasting debt of gratitude for the noble work he has undertaken in gathering together all available literature associated with Australia, and especially with New South Wales, and in making provision that the magnificent collection should, for all time, on his death, become the property of the people of his native state. [7]

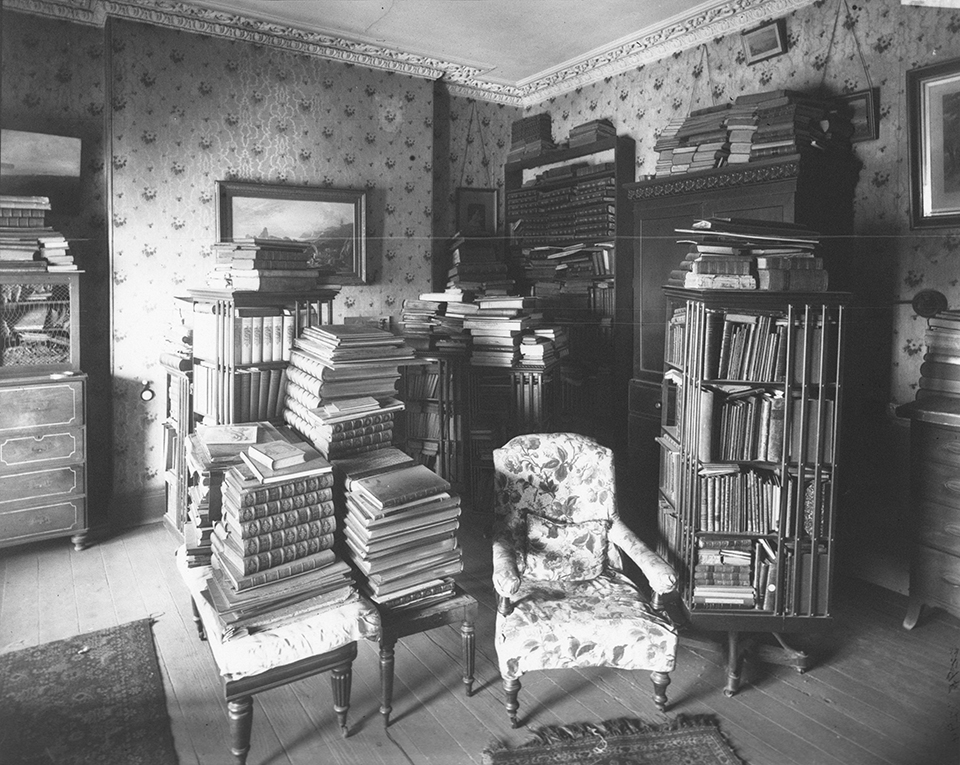

Mitchell's library [media]of approximately 40,000 volumes and his very large collection of manuscript journals, diaries and letters, thousands of prints, maps and charts, pictures and portraits, miniatures, bookplates, coins and medals, were formally handed over to the Trustees of the Public Library, under the terms of his will.

…I give and bequeath to the Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales all my books, pictures, engravings, coins, tokens, medals and manuscripts … upon the trust and condition that the same shall be called and known as 'The Mitchell Library' and shall be permanently arranged and kept for use in a special wing or set of rooms dedicated for that purpose… [8]

Much of the collection was placed in damp-proof boxes in the vaults of two Sydney banks until the Mitchell wing was ready for occupation. Mitchell's pictures were temporarily housed the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

The Howie brothers completed the building work in March 1908, under the watchful eye of George McRae, best known today as the architect of the Queen Victoria Building. It was another two years before the interior floors, furniture and finishings were ready to be opened to the public. The Mitchell library officially opened its doors on 9 March 1910.

Just over 100 years later, Mitchell's bequest to Sydney, to New South Wales and to Australia, remains remarkable. He appreciated the importance of encouraging Australians to acquire a fuller knowledge of their own culture, and he claimed that the main object of his life had been to enable future historians to 'write the history of Australia in general and New South Wales in particular'. [9] As then State Librarian and Chief Executive Regina Sutton noted at the time of the centenary,

David Scott Mitchell's bequest was more than a very generous cultural gift. It at once created a substantial public research collection in an area in which there had been none. That area was one which was crucial to the nation – the study of Australia itself. In this sense, it is no exaggeration to say that Mitchell's gift is the nation's greatest cultural benefaction. [10]

References

Ellis, Elizabeth. A Grand Obsession: The DS Mitchell Story. Sydney: State Library of NSW, 2007.

Fletcher, Brian H. Magnificent Obsession: The Story of the Mitchell Library, Sydney. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2007.

Jones, David J. A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826. Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988.

Richardson, GD. 'Mitchell, David Scott (1836–1907).' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/mitchell-david-scott-4210/text6781. Published in hardcopy 1974, viewed online 4 June 2015.

Notes

[1] Elizabeth Ellis, A Grand Obsession: The DS Mitchell Story (Sydney: State Library of NSW, 2007) 11; FREE PUBLIC LIBRARY, The Sydney Morning Herald, September 14, 1900, 2, viewed 8 July, 2015, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article14336170at http://trove.nla.gov.au/ndp/del/article/14336170

[2] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 34

[3] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 43

[4] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 43

[5] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 45

[6] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 45

[7] Quoted in David J Jones, A Source of Inspiration and Delight: The Buildings of the State Library of New South Wales Since 1826 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales, 1988), 50

[8] David Scott Mitchell, Last Will and Testament of David Scott Mitchell of Darlinghurst Road Sydney...Certified copy (typescript) dated 24 July 1907, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library collection, Safe 3/20, a928383

[9] Brian H Fletcher, Magnificent Obsession: The Story of the Mitchell Library, Sydney (Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, NSW 2007), 35

[10] Regina A Sutton, 'Foreword' in Elizabeth Ellis,' A Grand Obsession: The DS Mitchell Story (Sydney: State Library of NSW, 2007), vii

.