The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Randwick

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Randwick

Land of swamps and heath

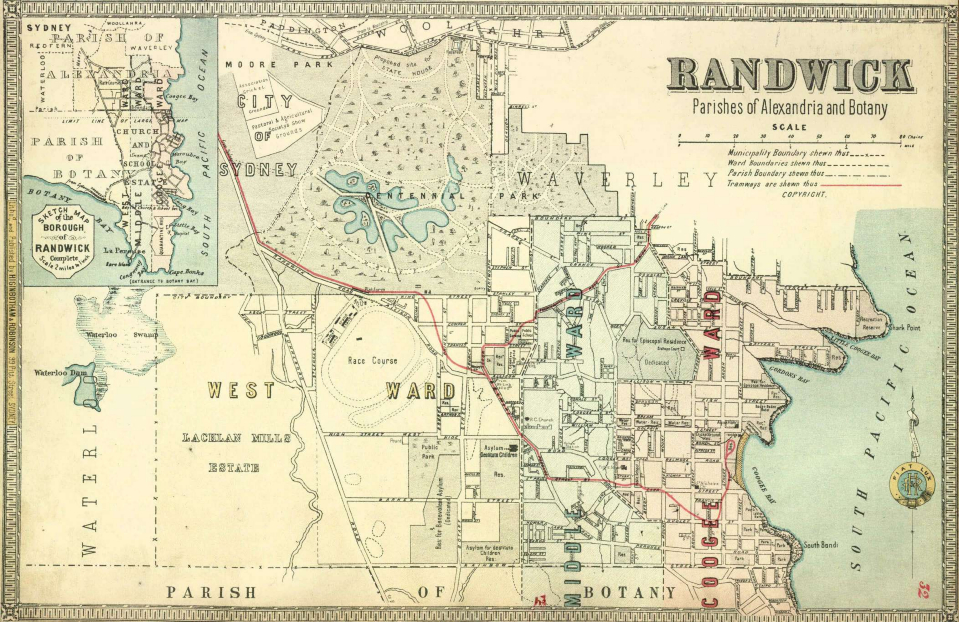

[media]For thousands of years, Indigenous people lived in what was once a land of swamps and heath vegetation in south-eastern Sydney where the City of Randwick is now located. [1] This local government area – including the suburb of the same name – stretches from Centennial Park, on the edge of the Sydney CBD, to Botany Bay.

In 1995, on a high ridge between Sydney and the coast, an Aboriginal hearth, or campsite, was discovered off Avoca Street. Dated to 8,000 years before the present, it was the oldest such site in coastal Sydney at that time. Because of fluctuating sea levels, Indigenous people only lived in a relatively stable coastal environment for the last 6,500 years, so this site is exceptional as it one of the few in Sydney predating this period. [2]

[media]In the first half of the nineteenth century only a small number of European settlers lived in this district. While some had land grants, all early settlers benefited by a contribution from the public purse, made possible by the colonists' exploitation of Aboriginal land. [3]

[media]The decision in the 1850s to transplant destitute children from central Sydney into this rural locality was pivotal in bringing the attention of Sydney society to the district. The Asylum for the Relief of Destitute Children was officially opened in 1858 and, although initially celebrated, it became increasingly crowded and scandal-prone as instances of abuse occurred. When it was determined in 1915 that the facility was needed for servicemen returning from World War I, the children were dispersed and the suite of magnificent sandstone buildings on Avoca Street – constructed between 1856 and 1880 – were transformed into a hospital. When the heir to the British throne visited Australia in 1920 this was named the Prince of Wales Hospital. [4]

[media]In this land of swamps and heath, horseracing was held spasmodically from the 1840s at what was known as the 'sandy track'. From the 1860s this track was a permanent fixture and so Randwick became one of Australia's pre-eminent centres for horse racing. Horses were a vital part of colonial life and being able to handle one was as necessary as the ability to drive a car is today. In the 1860s, horseracing was regarded as the 'national pastime' and for Australians the name 'Randwick' became synonymous with horseracing. [5]

Randwick village

[media]While the asylum and the racecourse gave the district a public profile, the village of Randwick emerged in the 1850s largely from one man's vision. English bounty migrant Simeon Henry Pearce bought property in the area, naming it 'Randwick' in honour of his Gloucestershire village. Randwick began to take on the air of an English village when a vacant space opposite the asylum, near cross roads, began to be called, as in the English Randwick, the 'High Cross'.[media] A devout churchman, Pearce chose the site for a church, schoolhouse and parsonage nearby and an additional area for burial grounds on Crown land set aside for these purposes. A complex of nineteenth century buildings would eventually line Avoca Street with the first temporary St Jude's Church of England and schoolhouse – largely supported by government funds – opening on 23 May 1858. [6]

East of Randwick, another village began to develop in the 1850s, even though coastal Coogee had been formally surveyed in 1838. Largely as a result of the need to pay for the upkeep of the road joining these villages, a local government area was incorporated in 1859. With Simeon Pearce as its first mayor, the Municipality of Randwick experienced some difficult early years, and animosity between Randwick and Coogee reached a climax in the early 1860s over the building of a second St Judes Church. Completed in 1865, this became the centre of Randwick village life, as churches were in English [media]villages. [7]

While religion was a binding force in colonial New South Wales, it also drove a wedge through society. This was particularly the case as sectarianism, fuelled by British and Irish politics, took hold in the second half of the nineteenth century. A complicating factor was the attempt to make the Anglican Church an established religion in New South Wales, as in England. As this did not happen, other Christian religions thrived. [8]

[media]On 6 May 1888 Cardinal Moran presided at the opening of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart Church in Avoca Street. This Catholic church was designed by architects Sheerin and Hennessy, of Pitt Street, while builders Eaton Brothers from the North Shore undertook construction. [9] Two years later the district's Presbyterians also built a new church, located on the highest point of the municipality near the junction of Alison Road and the tramline. Aware of a demand for 'a distinct type of Australian ecclesiastical edifice', architects Sulman and Power of George Street designed this red brick church, faced with stone, to meet local climatic conditions. [10]

[media]Pubs also filled an important social function in English and Australian villages. Publican John Grice, the village postmaster until 1864, provided a civilised, affordable service, selling drinks at town prices and mounting shows at holiday time. Band performances, dancing on the green, quoits and skittles were all held at the Vauxhall Gardens adjoining his Coach and Horses Hotel. [11]

Generally the village of Randwick was a place of well-behaved people where royal events were much anticipated. Special days of celebration in the colony helped reinforce imperial loyalty and devotion to the British royal family. Randwick's celebrations for the Prince of Wales' wedding in 1863 were long remembered and five years later, there was even greater excitement when, as part of the first royal tour of Australia, Queen Victoria's son Prince Alfred the Duke of Edinburgh visited Randwick. [12]

[media]Another British hero was memorialised when, in October 1874, sculptor Walter McGill's statue of Captain Cook was unveiled. It still stands at the junction of Avoca and High Streets, in front of a castellated building, which has variously housed a residence, a school, a pub and a restaurant. [13]

Suburbanisation

[media]Between 1860 and 1910 the northern part of Randwick Municipality changed from a comparatively rural area to near continuous suburban sprawl. Commuting was made possible by a reasonably efficient public transport system, consisting of horse buses and later an extensive tramway network, constructed between 1880 and 1921. [14] In this first phase of suburbanisation, grand houses such as Sandgate in Belmore Road – originally called Kilkerran – a twin-gabled sandstone home, was built in the 1870s. [15] Ventnor, a two-storey, sandstone house with ocean views, built by Randwick mayor George Kiss, was also constructed at this time in Avoca Street [16] [media]Other surviving nineteenth century buildings in this street include Randwick Town Hall and council chambers, an Italianate building opened in 1882, designed by architects Blackman and Parkes. [17]

Randwick's population [media]rose sharply in the interwar years. This growth is only partly explained by the growth of industry, as many workers, at the Randwick Tramway Workshops for instance, came from outside the municipality. A concentrated residential population was possible because of the uncontrolled growth of flats at this time, many of which still serve their original function. [18]

The turbulent politics of World War I and the interwar years impacted on Randwick with strikes and unrest at some of its large industrial complexes where militant unionised workers were employed. The community came together as one, however, in May 1925 when a cenotaph in memory of the 4,000 Randwick men who had fought in World War I was unveiled by the governor general Lord Forster. [19]

[media]Dramatic changes took place in Randwick in the postwar years. Leisure patterns changed, and as the impact of television (first seen in Sydney in 1956) was felt, patronage of the interwar picture theatres declined. Many were demolished or the buildings used for other purposes. The Odeon in Randwick, which closed in 1980 to be replaced by a shopping centre, survived longer than most. A successful fight was waged, however, to save a fine example of inter-war architecture, the art deco Ritz theatre at the Spot. [20]

[media]Although local councils were supposed to abide by town planning principles, this was seldom the case. As development accelerated in the 1960s, and high-rise buildings proliferated, Randwick Council seemed to have little input into the process. When the historic Newmarket Stable and selling yards in Young Street and a group of nearby cottages were threatened during the rezoning of The Spot in 1976, the Randwick Struggletown Association, using the name supposedly once attached to this area, successfully fought the proposed [media]rezoning. [21] [media]With the Wran Labor Government's revision of planning laws in the late 1970s, and the introduction of heritage legislation, permanent conservation orders were placed on historic buildings, including St Judes Church. This ensured the survival of iconic buildings such as the 1897 Randwick post office building and, fronting Alison Park in the Avenue, the 1888 Avonmore Terraces, described as the 'finest Italianate terraces in Sydney'. [22]

Nevertheless a remarkable feature of Randwick over the last 30 years has been the spread of high-rise buildings, as low-rise interwar streetscapes make way for congested centres lined with glass-fronted, eight-storey buildings. Only remnants of the English village remain. [23]

Reading list

Curby, Pauline. Randwick. Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009.

Notes

[1] Arthur Phillip, The voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay: with an account of the establishment of the colonies of Port Jackson & Norfolk Island; compiled from authentic papers which have been obtained from the several departments; to which are added the journals of Lieuts. Shortland, Watts, Ball & Capt. Marshall, with an account of their new discoveries, facsimile reprint of first edition printed by John Stockdale, London, 1789 (Richmond, Victoria: Hutchinson of Australia, 1968), 63

[2] Joseph Waugh, ed, Aboriginal People of the Eastern Coast of Sydney: Source Documents (Randwick, NSW: Randwick & District Historical Society, 2001), 43; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2002), 37–39, 56

[3] Pauline Curby, Randwick (Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009), 31

[4] John Ramsland, Children of the Back Lanes: Destitute and Neglected Children in Colonial New South Wales (Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press, 1986); Frank Doyle and Joy Storey, Destitute Children's Asylum, Randwick, 1852–1916, edited by Ellen Waugh (Randwick, NSW: Randwick & District Historical Society, c1991); Pauline Curby, Randwick (Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009), 69–83

[5] Martin Painter, Richard Waterhouse, The Principal Club: A History of the Australian Jockey Club (North Sydney, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 1992) 3–12

[6] Brendan O'Keefe, Simeon Pearce's Randwick: Dream and Reality (Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press, 1990); Eileen Price, Some Market Gardeners in Randwick and Coogee 1840s–1880s (Randwick, NSW: Randwick & District Historical Society, 2000); K Cable, 'Mrs Barker and her Diary,' Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 54, 1 (March 1968) 92–94; Pauline Curby, Randwick (Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009), 47–67

[7] Frederick Arthur Larcombe and Wilfred Brian Lynch, Randwick 1859–1976, revised edition (Sydney: Oswald Ziegler Publications for the Council of the Municipality of Randwick, 1976) 33–38, 63–70, 80–88, 105–108; Lionel Frost Bowen, Early Coogee and Randwick: Evidence from the St Jude's case 1861–1862 (Randwick, NSW: Randwick & District Historical Society, 1998); Pauline Curby, Randwick (Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009), 122–23

[8] Kenneth Cable and Stephen Judd, Sydney Anglicans: A History of the Diocese (Sydney, NSW: Anglican Information Office, 1987), 74; Keith Amos, The Fenians in Australia 1865–1880 (Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press, c1988)

[9] The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1888, 4

[10] Illustrated Sydney News, 4 April 1890, 23

[11] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1864, 1; The Sydney Morning Herald, 1 January 1867, 8; The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 December 1871, 8

[12] The Sydney Morning Herald, 12 June 1863, 1; The Sydney Morning Herald, 13 June 1863, 4; The Sydney Morning Herald, 17 February 1868, 4

[13] The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1874, 5

[14] D Audley, 'Sydney's Horse Bus Industry in 1889' in Garry Wotherspoon, ed, Sydney's Transport: Studies in Urban History (NSW: Hale & Iremonger in association with the Sydney History Group, c1983), 81–83; David R Keenan, The Eastern Lines of the Sydney Tramway System (Sans Souci, NSW: Transit Press, 1989)

[15] Eastern Herald, 27 August 1987; 'Sandgate,' New South Wales Office of Environment & Heritage with Heritage Council of New South Wales, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/visit/ViewAttractionDetail.aspx?ID=5045450, accessed 21 September 2015

[16] Town and Country Journal, 16 August 1873, 208–09

[17] The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 February 1882, 6

[18] R Cardew, 'Flats in Sydney, the 30 per cent solution?' in J Roe, ed, Twentieth Century Sydney, Studies in Urban and Social History, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1980, 74

[19] The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 May 1925, 10

[20] Randwick Bugle, Easter, 1993

[21] Eileen Price, The Spot: 1850–1890 (Randwick, NSW: Randwick & District Historical Society, 1998)

[22] John Toon and Jonathan Falk, eds, Sydney: Planning or Politics: Town Planning for Sydney Region Since 1945 (Sydney: Planning Research Centre, University of Sydney, 2003)13; The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 August 1979

[23] Pauline Curby, Randwick (Randwick, NSW: Randwick City Council, 2009), 372

.