The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Mitchell

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Mitchell Library

Libraries are the most personal institutions. History never forgets those who found them. Book burners are execrated; book donors are remembered forever. For centuries, great benefactors have had naming rights: Thomas Bodley in Oxford, Cardinal Mazarin in Paris, Andrew Carnegie all over America and in Sydney, David Scott Mitchell.

[media]Waiting for some boxes in the Mitchell one day – those fifteen minutes can seem like forever when you're hungry to start – it struck me I've been using the building intermittently for nearly half its life. Someone brought me to the old reading room in the 1950s when I was still at school and I was bowled over by the faint green light from the ceiling, the vertigo stairs and peculiar smell of linoleum. I was at university before I took a right turn at the map of the world and walked through those swing doors into the crowded, serious, forbidding space of the Mitchell. Two things survive 40 years later: the impossible card catalogues and the stern tenderness of the staff.

I was back the other day to track down the details of a little scandal in the theatre world, a story almost forgotten except by those it touched in the late 1970s. We forget so quickly in this town. Amnesia has been a governing principle of Sydney since the earliest days. The Mitchell is the city's office of corrections, the place we come to set the record straight. After a few hours I found the few paragraphs I needed in a misdated edition of a defunct magazine and gave the researcher's inner whoop of triumph. These Eureka moments have a thrill it's almost impossible to convey. Grey faces in libraries around the world mask inner lives of considerable emotional volatility. We know the ups and downs. Weeks of tedium are wiped away in a few moments of discovery. Research is pure pleasure.

Like nurses in a ward of the slightly unhinged, the librarians stand at their posts attentive and detached. These are the intermediaries between us and the Mitchell's hidden riches. We can't go where they go, down into the stacks where all the papers lie. Nor can we hope to be as fluent as they are in the old and half-forgotten language of the catalogues. They know what the numbers mean. They know the ways in.

We're on our honour with them. At the Library of Congress in Washington, uniformed giants with high calibre weapons stand by in case of trouble. Security at the Mitchell depends on interrogation and sharp eyes that have seen just about everything in their time. Every time we present a call slip at the counter we're lightly grilled. Then the slips are torn apart with a crisp little rip that says we've passed muster and this transaction is over. Fifteen minutes later, brown cardboard boxes appear from below, all ours until we're done.

The recluse of Darlinghurst Road

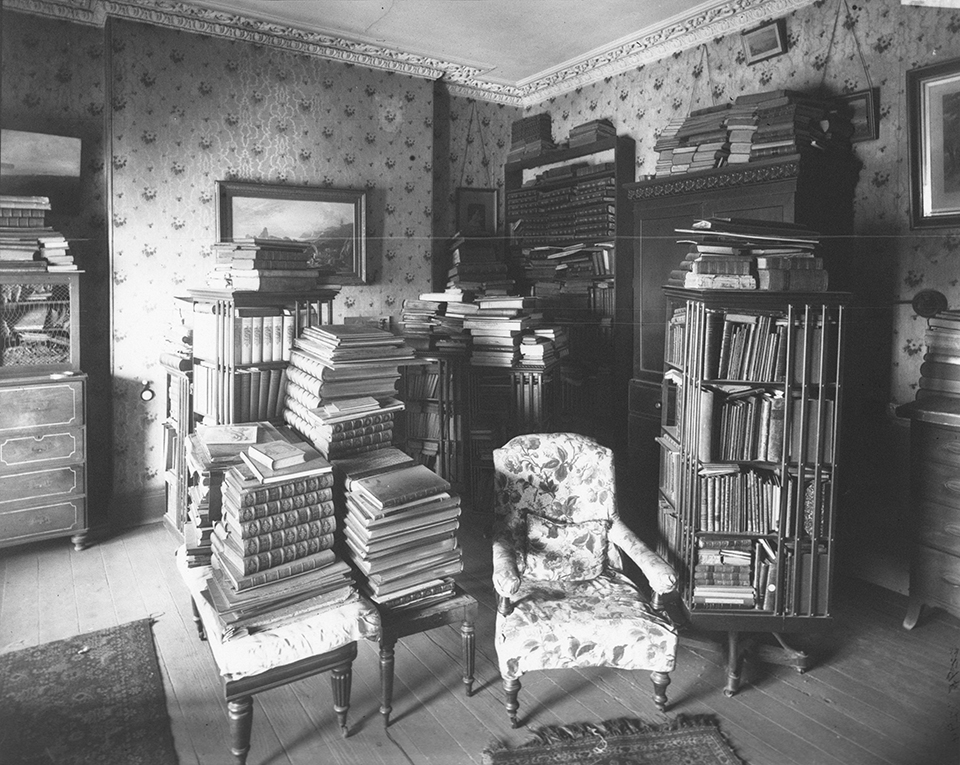

[media]In a handsome house in Darlinghurst, Mitchell camped in rooms stacked high with books. The place was neglected inside and out. 'It was pathetic: dust, cobwebs, a musty smell, no real sign of domestic care,' wrote Robert Scot Skirving, the doctor attending him in his last weeks. 'Furniture, probably valuable; pictures, certainly so; and books and more books and yet more books, everywhere and anyhow.' [1] Mitchell had broken off with society and withdrawn into the house on the death of his adored mother. For nearly 40 years he ate chops and rarely went out except to buy books. He only ever left Sydney once or twice in his life. He never left Australia. Apart from the scholars he let through the door, Mitchell's only companions at 17 Darlinghurst Road were an Irish housekeeper and an ancient sulphur crested cockatoo.

He was bidding for books when he was still a child. This passion for books came to him from both sides of his family. He never worked. The money came from Hunter Valley coal. Before his retreat from the world, Mitchell played whist, danced and performed in theatricals at Government House. Comedy and farce were his strength. 'A part that could not be identified with his real self he played with gusto,' Arthur Jose reported in The Lone Hand. 'Parts that could, by any possibility be thought self-revelatory, he shrank from taking.' [2] A connoisseur of Shelly, Browning and the Elizabethan dramatists, Mitchell was rather amused by local efforts. Yet even as a young man he began, he told his cousin, Rose Scott, to:

…get all the Australian literature I come across not so much for intrinsic merit which I am unpatriotic enough not to find in them as that I think some day anything like a complete collection of Australian books will be curious. [3]

Yet it was not until the last twenty years of his life that Mitchell abandoned all other collecting to concentrate on accumulating Australiana. Like nearly so much else in his life, the reasons for this remain a mystery. The looming celebrations for the 1888 centenary sparked fresh interest in Australiana among both booksellers and collectors. And Mitchell was in his own way a patriot. Wrote Jose,

He was proud of his family; he was proud of his state…Of Australia and of New South Wales especially as embodied in Sydney, he was a proud and faithful son; and he set himself to collect and treasure every document that threw light on things Australian, as a son might seek out and treasure every scrap of writing that could refer to his dear parents and his famous ancestry. [4]

Mitchell's ambition was to own everything in his field. To possess one prized bundle of papers, he would buy another man's whole collection. His deep pockets were known to the trade in London, Amsterdam and Sydney. He had the determination and money to outwit most other collectors of Australiana most of the time. 'He haunted the bookshops of all grades,' wrote Jose

He rarely shut his door – otherwise not readily opened – on any man who had material to show. During the last twenty years of the century there were few Mondays which did not see him take a cab to the city ('Three Hours' the cabmen called him, because he was sure to keep them, at least, so long) in search of his new trouvaille. [5]

And he sleuthed for finds in the society from which he had all but disappeared. GD Richardson, the post war Mitchell librarian, recalled:

He badgered his friends into selling choice items. Through his earlier social connections he obtained much that would otherwise not have been offered to him…and on occasion he obtained choice items from members of old families in straightened circumstances. [6]

Mitchell knew the living underrate the history of their own times. He had no truck with the contemporary wish to hide evidence of convict stains. 'The main thing is to get the records,' he told HCL Anderson, the Principal Librarian of what was then called the Free Public Library, 'We're too near our own past to view it properly, but in a few generations the convict past will take its proper place in the perspective…' [7] He knew the study of Australia couldn't be divorced from the study of the Pacific and, indeed, Antarctica. Though books were his principal obsession, wanting everything in his field meant also hoovering up papers, pictures, medals, erotica, maps, miniatures, letters, charts, broadsides, proclamations and coins until by the end of the century his collection was the biggest of its kind in the world. A witness told the Public Works Committee in 1905:

If Mr Mitchell's library were burnt tonight, the history of Australia could not possibly be written…because he has the original documents. [8]

The gift, and the life, a mystery

His commitment to candour didn't extend to his own affairs. Sketchy reports of his life reveal a man who was shy, reserved, in precarious health and suspicious of the celebrity that would come to attend his name. Such was his mania for privacy that the last image we have of him is a photograph taken at about the age of 35. The library's handsome portrait by Norman Carter was done to honour the great donor eighteen years after his death. The recluse of Darlinghurst Road refused even to pose for a bust which the government of New South Wales wished to commission. Perhaps he had a point: by this late stage he was wizened, fragile and bald.

Mitchell entered his sixties buying on a greater scale than ever before but wondering what on earth would become of his hoard. He had never married. An engagement in his late twenties petered out. Richardson wrote: 'He shunned women.' [9] At some stage he warned his cousin Rose Scott: 'I have already told you, and I now repeat it, that in all probability I shall never ask anyone to share my lot.' [10] He was one of the confirmed bachelors the nation has a good deal to be grateful for. Another was Sir Alfred Felton who bequeathed £2 million to the National Gallery of Victoria. A third was Sir William Dixson whose name would come to be honoured alongside Mitchell's in establishing the library. Two fortunes – coal and tobacco – bequeathed by two bachelors were at the heart of the project.

It might not have happened. So suspicious was Mitchell of the politicians of New South Wales that for years he was deterred from leaving his collection to the state. He toyed with a huge gift to Sydney University. Jose claims there were times Mitchell 'reckoned it wiser to let the library be dispersed after his death by an auction sale, in order to encourage new collectors.' [11] The head of the old library took on the task of talking Mitchell round, a task Anderson handled extraordinarily well considering both men disliked and distrusted one another. Business was their link. The library withdrew from the Australiana market leaving Mitchell a clear run. Within three years, the collector was ready to promise the library his treasures. When news of the gift broke in 1898, the invisible collector of Darlinghurst became a public figure on whom poured down the thanks of a grateful New South Wales.

[media]But these were terrible times. Drought and bank busts had left Australia in deep depression. The minister responsible for building the new library – 'and make provision therein for keeping the collection by itself and making it freely available for students of Australasian history' [12] – was a bush Philistine of the old school. Year after year, nothing was done. The donor, his health failing, insisted the building be ready within a year of his death or the gift would fail. A providential change of ministry allowed the project to begin at last. After a good deal of colourful bickering about the site, construction began in April 1906 with Mitchell the Banquo at all ceremonies.

Scot Skirving was summoned to Darlinghurst Road about a year later. Having battled his way past the housekeeper and into a squalid bedroom, he found 'a very sick man, probably sick unto death.' [13] Mitchell was in the last stage of pernicious anaemia, a then-untreatable condition that prevents the body taking up vitamin B12. He was feeble, tiny and yellow

I wanted badly to be decent and useful to this interesting and useful man. After some perfectly banal sentences, he looked at me and spoke as follows: 'I have sent for you not because I wish to be treated, for I am done with this world and am indifferent to life. I've merely wished to have someone sign my death certificate, and so cause no trouble.' The doctor rallied the relatives and 'got a nurse or two into that house of piggery, and things were straightened up. The patient was washed and nursed till the end came, I think on 24 July 1907. [14]

It's [media]said, but surely this is too good to be true, that very shortly before his death Mitchell secured a prize he had been after for most of his life: a copy of the earliest book of verse published in the colony, Barron Field's First Fruits of Australian Poetry. [15]

Mitchell's house, its long-guarded privacy violated, was photographed inside and out before its contents were carted off in damp proof boxes to the vaults of the Bank of Australasia where they were stored until the new building was ready. So rushed was the operation that no inventory of the treasures was ever made. The scale of his bequest has been guessed at for the century since. [media]The old claim of 60,000 items was an exaggeration. In preparation for the Mitchell Library's centenary celebrations, roughly 40,000 items were found in the Mitchell stack bearing some trace of the great collector's bookplate or signature. But we'll never know what he gave. The gift, like the life, has kept its mysteries.

In his blood – Patrick White at the Mitchell

'The Mitchell to this day frightens me stiff,' Patrick White told a couple of hundred librarians assembled there in 1980. [16] His confession contained, as usual, only enough truth to put us off the track.

In the State Library and the hallowed Mitchell, the frivolous side of my nature finds itself at variance. I can never concentrate. I am really more interested in people than ideas, so my attention continually strays from my book to the faces around me. Perhaps it's all to the good in a novelist, but it sometimes makes me feel an impostor sitting amongst so many serious people… [17]

As a White and a writer, the Mitchell was in his blood. He was there at the age of three at the official handover of his uncle's immense stamp collection, clattering over the floors until a librarian called Miss Flower silenced him. 'SSSSSh! All the poor people are reading.' He thought she meant they were sick.

I looked round and couldn't see any signs of sickness in the readers. It rather puzzled me, but she didn't give me time to work it out or ask questions. She led me up to an enormous, yellow-brown globe, and set it spinning to attract my attention. I found it momentarily of far more interest than any sheets of black old stamps or sick readers. [18]

[media]Thirty years later, having published two novels in London and fought with the RAF in Africa, he was back. After posting the manuscript of The Aunt's Story to his publisher in New York in January 1947, White spent much of that late summer in the Mitchell researching the novel he planned to write next, a novel about an explorer. He found the letters and journals of Ludwig Leichhardt the inept and ungrateful visionary who would become the model for the tragic Johann Ulrich Voss. In those months – and again when he returned to the abandoned novel nearly a decade later – White plundered the resources of the library for the details his imagination craved of Sydney in the 1840s and of Leichhardt's expeditions to the interior. His notebooks follow the doomed explorer every step of the way:

23rd Two mules nearly drowned. Flour & sugar saturated. Spade lost, and portfolio containing insect specimens. 24th Blacks near Comet River throw up their hands, screamed and ran away. Camped on backwater of river. Rain. [19]

Working in the Mitchell was a democratic business. Great writers, hacks and visionaries, students and law clerks sat side by side under a low ceiling with the fake portrait of Mitchell keeping an eye on their labours. No privileges were extended to the famous. 'It felt like scholarly heaven with helpful staff and fast, efficient delivery of material,' [20] the novelist Peter Corris recalls of the place in the late 1960s:

Manning Clark was there, also Brian Fitzpatrick and others. Later, I met Robert Hughes when he was researching The Fatal Shore and I was researching colonial prize fighting. He had the linen jacket and the hat and was very pleasant. There were seductions on the grass (but not consummations) in the Botanic Gardens and the Metropole was the scholars' pub. [21]

Some questions of library practice deserve better attention. Sleep: the struggle to stay awake on long afternoons. Wild enthusiasms: the importance of not inflicting them on library staff. Coffee and tea: how often is too often for the efficient scholar? (In the 1960s a strange little café that sold milkshakes and good pies was put into the roof. It saved exploring Macquarie Street for a feed.) Pencils: when to sharpen? Mood swings: the practical importance of ending the day on a high note. Beautiful people at the next desk: the subtleties of silent courtship.

Tramps rarely broached the defences of the Mitchell, but cold weather saw them gather in strength in the big reading room. So long as they didn't smell or snore, they were allowed to stay. One of these men became, in Patrick White's imagination, the simpleton savant Arthur Brown of Terminus Road, Sarsaparilla. Other writers put the library in their novels. In Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw set a gun battle in the reading room between revolutionaries in a post-apocalyptic city and 'a few men with no politics but a fanatic love for books [who] lay in the galleries and from prepared positions behind ramparts of books sniped at the mob that came in to make a bonfire.' Twenty men died for the books. 'It was quite a bloody affair.' [22] But the great novel of the library is The Solid Mandala into which Patrick White pours the sharp observations of twenty years spent working in both the reading room 'still smelling of varnish and rubber' and the Mitchell down the corridor.

Arthur's twin was Waldo Brown, White's portrait of a prim librarian who has, as it happens, done a little research on Barron Field. He dreams of writing but never lifts a pen. Waldo is valued by his superiors as 'a glutton for continuity' and he, in turn, loves

…the hallowed atmosphere of the Mitchell attached – all those brown ladies studying Australiana, and crypto-journalists looking up their articles for the Saturday supplements. [23]

A fearful scene occurs when his colleague Miss Glasson points out a tramp who is often there reading the Bhagavad Gita, the Upanishads and Japanese Zen. To Waldo's horror he sees his brother dressed in a heavy overcoat 'munching and mumbling' over a copy of The Brothers Karamazov. After a whispered altercation about the point of reading Dostoyevsky – Arthur says: 'I could be able to help people – Waldo throws him out of the library.

Arthur did not look back, but walked in his raincoat, over the inlaid floor, through the hall. Nor did the Lithuanian attendant, from some charitable instinct, attempt to arrest the offender, for which Waldo was afterwards thankful. [24]

While he waited for this bleak portrait of the library and its librarians to be published, White was back in the Mitchell researching the social landscape of Sydney in the 1920s, and cocaine sniffing in the post war theatre world. He was still terrifying library users into the 1970s, this famous and absolutely unapproachable figure, wrapped usually in a raincoat, sitting just there. That was in the old Mitchell where the famous and the obscure worked side by side not so much on a level playing field as a creaking parquet floor.

Eureka

The weight of paper in the building and the Medici tendencies of Neville and Jill Wran provoked the government of New South Wales to build the Macquarie Street wing in the 1980s. This delivered the library's vast reading room to the Mitchell. Like the prisoners in Fidelio, its inhabitants clambered out of the darkness into the light. And no sooner were they sorting their pencils that we began to wonder if libraries of paper would be around much longer.

The future may be electronic, but the Mitchell still has to guard the past. Whatever efforts are put into digitising – such an ugly term – old books and papers, the originals must still be preserved. Whatever miraculous ways are found to hunt electronically through old records we will still need librarians with long memories and sleuthing skills to take us where we want to go. As more and more documents start life in electronic form – so malleable and so dull – we may come to value paper even more highly in the future than we have in the past.

We'll fill in a slip; endure another brisk interrogation; kill fifteen minutes by scanning faces; unpack a box of treasures heavily defended in manila envelopes; and hold in our hands the real thing: the letter, the book, the will, the diary, the sketch. And once in a while – perhaps not by accident – we will come across one of Mitchell's gifts identified by the bookplate he designed not long before his death. Beneath the rather bogus wreaths and helmets and shields is the motto readers, researchers and collectors all live by. It's just one word: Eureka.

References

GD Richardson in Descent, vol 1, no 2, 1961

Robert Scot Skirving, Memoirs of Dr Robert Scot Skirving 1859–1956, edited by Ann Macintosh, Foreland Press, Darlinghurst, NSW, 1988

Patrick White, 'The Reading Sickness', Patrick White Speaks, Jonathan Cape, London, 1990

Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907

Notes

[1] Robert Scot Skirving, Memoirs of Dr Robert Scot Skirving 1859–1956, edited by Ann Macintosh, Foreland Press, Darlinghurst, NSW, 1988, p 259

[2] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, p 467

[3] Letter from DS Mitchell to Rose Scott, 19 July 1868, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library collection, ZA1437, pp 79b–82

[4] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, pp 467–68

[5] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, p 468

[6] GD Richardson in Descent, vol 1, no 2, 1961, p 9

[7] Frederick Wymark, 'David Scott Mitchell', 1939, introduction, typescript, p 19, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library collection, AM121/1

[8] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, p 468

[9] GD Richardson in Descent, vol 1, no 2, 1961, p 11

[10] Letter from DS Mitchell to Rose Scott, undated, papers of Rose Scott, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library collection, A1437, p 273b

[11] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, p 469

[12] Arthur Wilberforce Jose, The Lone Hand, 2 Sept 1907, p 469

[13] Robert Scot Skirving, Memoirs of Dr Robert Scot Skirving 1859–1956, edited by Ann Macintosh, Foreland Press, Darlinghurst, NSW, 1988, p 259

[14] Robert Scot Skirving, Memoirs of Dr Robert Scot Skirving 1859–1956, edited by Ann Macintosh, Foreland Press, Darlinghurst, NSW, 1988, p 259

[15] Barron Field, First Fruits of Australian Poetry, first published George Howe, Sydney, 1819; original in the collection of the Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[16] Patrick White, 'The Reading Sickness', Patrick White Speaks, Jonathan Cape, London, 1990, p 74

[17] Patrick White, 'The Reading Sickness', Patrick White Speaks, Jonathan Cape, London, 1990, p 74

[18] Patrick White, 'The Reading Sickness', Patrick White Speaks, Jonathan Cape, London, 1990, p 74

[19] Patrick White, notebook no 4, Patrick White Papers, National Library of Australia

[20] Peter Corris to the author, 13 July 2009

[21] Peter Corris to the author, 13 July 2009

[22] Marjorie Barnard and Flora Eldershaw, Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow, Virago, London, 1983, p 395

[23] Patrick White, The Solid Mandala, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1996, p 182

[24] Patrick White, The Solid Mandala, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1996, p 201

.