The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Corrangie / Harry

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Corrangie / Harry

Corrangie, called ‘Harry’ by the English settlers, was the husband of Bennelong’s sister Carangarang and known, after Bennelong’s death, as the ‘chief’ of the Burramattagal or Parramatta clan.[1],[2]

Judge Barron Field described Harry in 1825 as ‘gentle and well-bred’ and ‘the most courteous savage that ever bade good-morrow’.[3]

Early life

Born around 1787[4], Harry was taught to read as a child in the 1790s by the Reverend Samuel Marsden at Parramatta.

Writing in 1826 Marsden said that:

The Native Harry … lived in my family, 30 years ago, for a considerable time. He learned to speak our language, and while he was with me behaved well.

Marsden hoped Harry might ‘improve in civilization’, but he left to join the ‘Natives in the Woods’ and ‘never seems to think that he lost anything by living in the woods’.[5]

[media]Marsden taught several Aboriginal people, but it is possible that Surgeon James Thompson was referring to Harry when he published his ‘Curious and Interesting Account of the Original Natives of New South Wales’ in The New Wonderful Museum and Extraordinary Magazine in London in 1804:

The Rev. Mr. Marsden, chaplain to the colony, has a boy of one of the natives, which he has brought up, and intends educating, who writes a good hand, speaks our language with great fluency, sings hymns, and has a good ear for music. In short, from the account we have received, this child seems susceptible of all the mental endowments that can form the scholar and gentleman.[6]

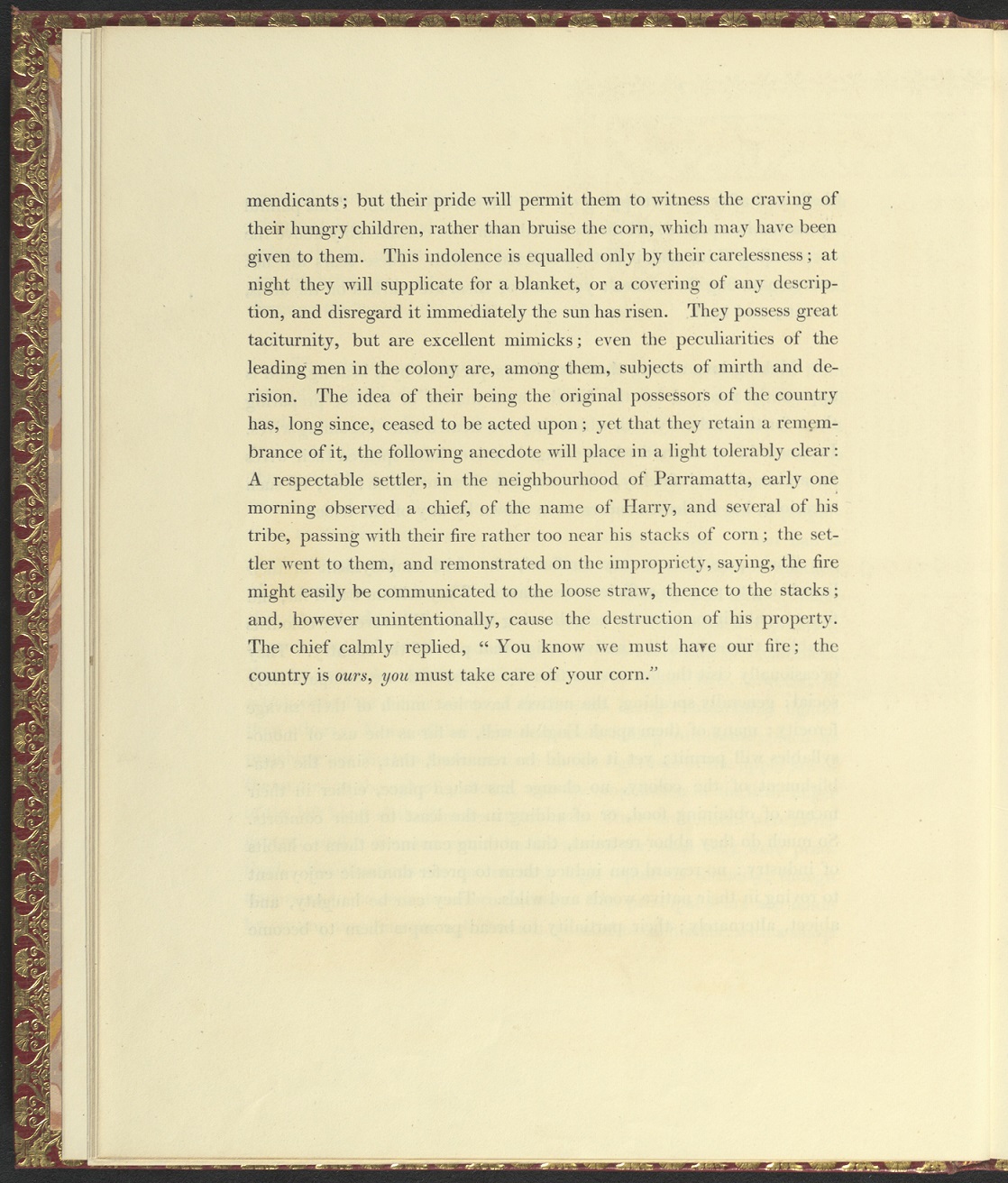

The country is ours

[media]The writer of the 1813 book Field sports &c. &c. of the native inhabitants of New South Wales said that Aboriginal people had not forgotten that the colonists in New South Wales were settled on land that belonged to them, and cited the words of ‘a chief, of the name of Harry’.

A respectable settler, in the neighbourhood of Parramatta, early one morning observed a chief, of the name of Harry, and several of his tribe, passing with their fire, rather too near his stacks of corn; the settler went to them, and remonstrated on the impropriety, saying, the fire might easily be communicated to the loose straw, thence to the stacks; and, however unintentionally, cause the destruction of his property. The chief calmly replied: ‘You know we must have fire; the country is ours, you must take care of your corn.’[7]

The poet of his tribe

Harry surprised the notoriously cantankerous John Macarthur with an erudite welcome speech in August 1817 when Macarthur returned to Parramatta with his two sons James and William after seven years of exile in England.

Macarthur’s youngest son William described at length Harry’s demeanour when he saw the men who had left New South Wales in 1809:

Harry hearing of our return, came to welcome us. He arrived whilst we were sitting at table after dinner. He was immediately brought in with a companion and placed at table. A glass of wine was poured out for each. The other native bowing to my father, drank his off. But Harry seemed to have his heart full, he hesitated a moment, then putting his hand on his glass, turned towards my father, and made a short but most beautiful speech. I regret much I cannot remember the words. But I remember thinking I had never seen manner more graceful or heard expressions better turned than his. He said that they had all mourned his absence, as for a father, and that he had not words to say, how much he rejoiced in his return – that there were many gone who would have rejoiced in that day as much as he did himself for that they always found a home and food and shelter with my father, when they needed it.—He then slightly alluded to the political troubles, which had occasioned my father’s long absence, – trusted that those things would never come again and that now he was once more amongst them, he would never again depart, but dwell in peace and at length lay his bones amongst them. I remember that some strangers who were present were much astonished at Harrys eloquence, to which I have done very ill justice – they did not know he was the poet of his tribe.[8]

Macarthur also spoke of Harry’s ‘gentle disposition’ compared with that of Tjedboro (Tedbury), son of the rebel leader Pemulwuy.

Harry’s Letter

In May 1890, the Reverend George Fairfowl Macarthur, a relative of William Macarthur’s, wrote to the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald describing a letter written by Harry in about 1807 to his mother when she was a girl. His mother, Maria Macarthur, was the daughter of Governor Philip Gidley King and his wife Anna Josepha:

Sir,—There was an old letter extant in 1848, which was written by an aboriginal named Harry, who was a very remarkable man, and one of the cleverest mimics to be imagined.[ .. ]the letter to which I refer was addressed to my mother, who had, at its date, returned with her parents to England. It commenced ‘My dear Maria.’ […] This letter, which I carefully read and examined, was expressed in far better language than many English people use. It spoke of the writer’s thanks for kindness which “Maria” had shown to him when she used to go with her mother, “Missus Gobernor,” to the school, and it told her that he had been down to “Wallamula to see the big ships.”

GEO. F. MACARTHUR[9]

In response to a query, he added several days later ‘I knew “Harry” and his contemporary “Bidgee Bidgee” personally and intimately, for as boys we were allowed to go out with them on excursion to hunt opossums and bandicoots.’

George F Macarthur’s recollections of his early life are not always entirely reliable but these notes, along with the manuscript by William Macarthur demonstrate the close relationship between the extended Macarthur family and Harry and other Aboriginal people in the Parramatta area.[10]

While in Sydney in 1833, the Austrian scientist Baron Charles von Hügel, was shown a letter he thought was written by Bennelong, ‘such as a child might write, in which he reminisced about the wife of Governor King’. [11] Judging by its content, this was not the well-known letter dictated by Bennelong and sent to Lord Sydney in August 1796, but Harry’s letter to ‘Maria’.[12]

Unfortunately the original of Harry’s letter has not been traced.

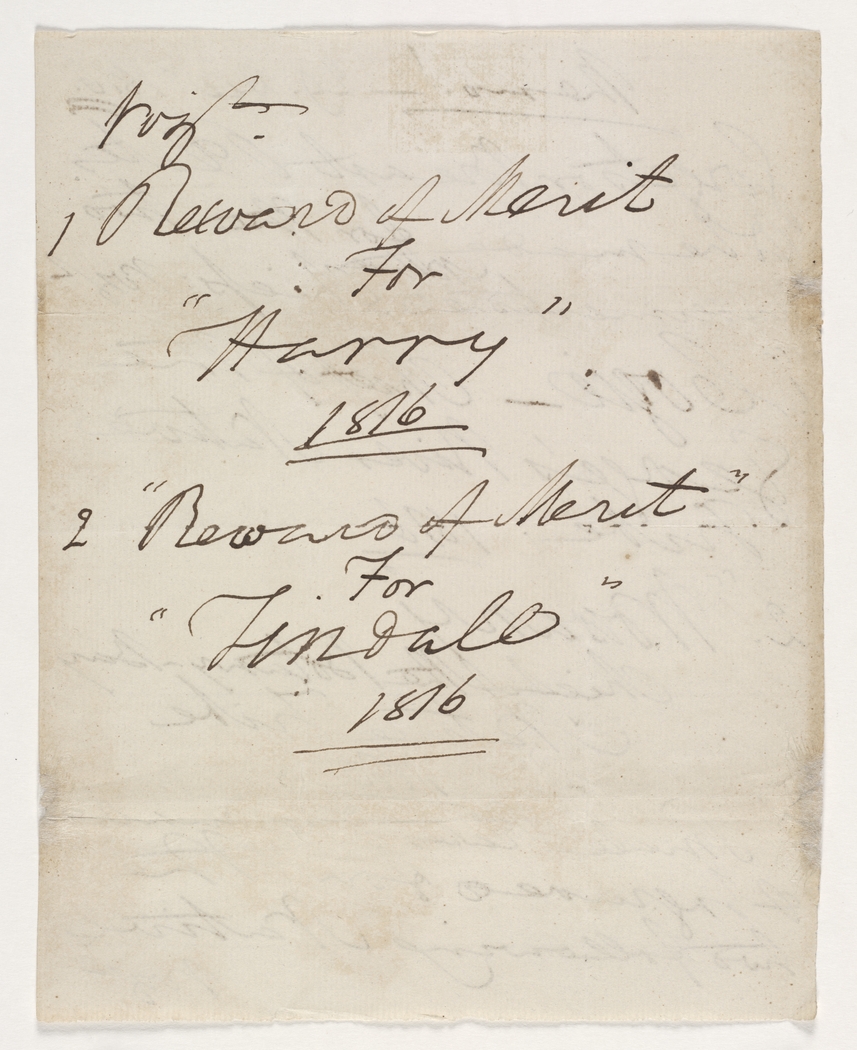

Guide in the Appin Massacre

[media]When Governor Lachlan Macquarie ordered a punitive expedition against ‘hostile natives’ in the Appin area in April 1816, Harry was listed as a ‘Black Guide’ with Captain Schaw’s detachment.[13]

As ‘Remuneration to Native Guides’, Macquarie gave Harry, Bidgee Bidgee, Tindall, Colebee (from Richmond) and Narragingy or ‘Creek Jemmy’ each a suit of slop clothing, a blanket, four days provision, a half pint of spirits and a half pound of tobacco.[14] Macquarie also ordered a ‘Reward of Merit’ plate to be engraved for Harry and another for Tindall.[15]

Carangarang

The earliest reference to the relationship between Bennelong’s sister Carangarang and Harry occurs in 1821, when Harry was about 34 and Carangarang about 50.[16] Carangarang had two children from an earlier relationship with Yuwarry, a son Carangaray, and a daughter, Kah-dier-rang. Yuwarry had died about 1802.

Carangarang was described in 1821 by a visiting English naval officer dancing and singing in a corroboree near James Squire’s farm at Kissing Point as about fifty years old, wearing an 'Opposum Cloake' and carrying a net bag over her shoulders. Her hair was a mass of 'Gorgon locks', decorated with eel bones, the 'brush of a native dog's tail, and a bunch of Emu feathers' behind' and identified as Carangarang, 'Sister of the well known Ben-ni-long [Bennelong]' and wife of Harry or Corrangie, acknowledged 'chief' of the Burramattagal (Parramatta clan), whose totem was the burra or eel’.[17]

Piper’s petition

With other Aboriginal people, Harry and Carangarang lived around Parramatta, at Kissing Point[18] on the Parramatta River where Bennelong had lived before his death there in 1813, and around the eastern suburbs of Sydney Harbour.

Captain John Piper sent a petition to Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane in July 1822 asking for clothes and blankets from the Commissariat Store on behalf of Harry, Carangarang, Carangaray[19] and others, camped near his mansion at Point Piper, who were ‘almost in a state of nudity, suffering Cold and hunger in the extreme’. Piper wrote:

In order to supplicate your Excellency for relief They solicited a White Man to put their unfortunate situation in writing for your Excellencys humane consideration, and as your Excellency has extended your benevolence to several of their suffering brethren, they humbly hope your Excellency will allow them some sort of covering from His Majestys store.[20]

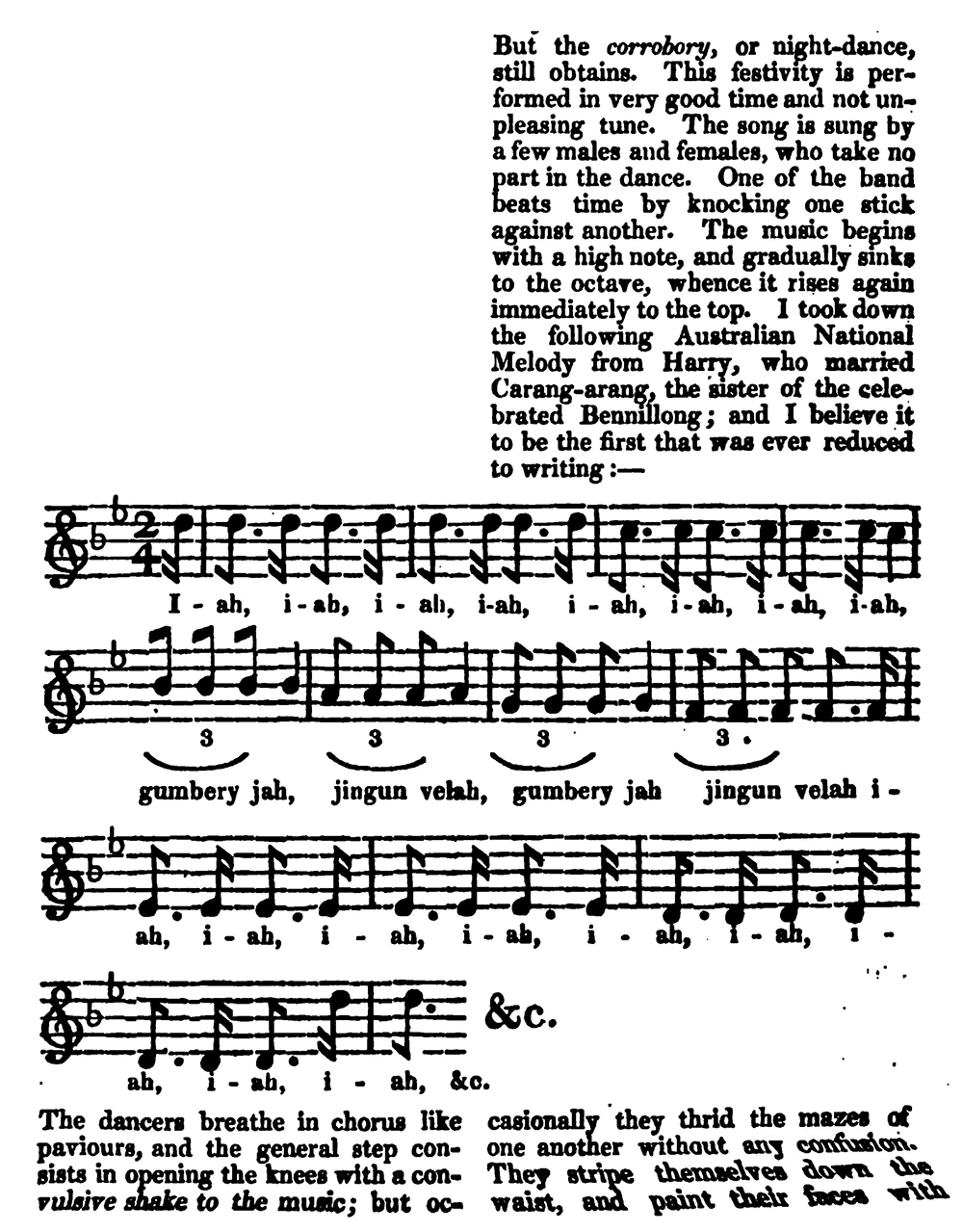

Harry’s song

[media]In 1823, The London Magazine published a ‘Journal of an excursion across the Blue Mountains of New South Wales’ by Judge Barron Field.

The article included a description of a corrobory (corroboree), and musical notation of a song of which Field says ‘I took down the following Australian national melody from Harry, who married Carangarang, the sister of the celebrated Bennilong; and I believe it to be the first that was ever reduced in writing.’

[media]Field published Harry’s Gumberry jah song again in 1825 in the Appendix to Geographical Memoirs on New South Wales.[21],[22]

Apprehending convicts

Harry, with two other Aboriginal people, Purcell and Margaret, confronted two escaped convicts from the Sydney Road work gang under the bridge in the Government Domain at Parramatta (now Parramatta Park) in January 1827.

He told the court that the convicts offered them a ‘large bundle’ of clothing, but ‘they (the ‘natives’) said no, we must have you; the prisoners then ran away, and the natives after, and apprehended them’. The bundle of clothing was identified as stolen by a Mr Beasley and the convicts ‘Michael Haze’ and ‘Wm. Ray’ were each sentenced to three years to ‘a penal settlement’.[23]

Later life

By the 1830s references to Harry are fewer. Ten years after apprehending the escaped convicts in Parramatta, Harry, Cora Gooseberry, ‘Bungarry’ (probably Toby Bungaree) and Maria (Toby’s wife), were charged in July 1837 with ‘creating an uproar in George-street’ while fighting under the influence of bull (watered down rum). According to the Sydney Gazette :

Through the instrumentality of Mrs. Gooseberry, they all pleaded guilty to the charge of drunkenness, and were each ordered to take a turn in the stocks, and at the same time informed that if they continued such a course they would be sent to the Tread Mill.[24]

‘Harry became quite an altered being long before his death’, wrote William Macarthur, ‘utterly broken down in body and mind by dissipation and disease.’[25]

Harry’s death is not recorded.

References

‘Harry’, in Keith Vincent Smith, Wallumedegal: An Aboriginal history of Ryde, North Ryde: City of Ryde, 2005, 23-24

Notes

[1] The French surgeon and pharmacist René-Primavère Lesson, who visited Sydney in 1824, named ‘Hari’ (Harry) ‘chef de la peuplade de Paramatta [sic]’, that is, leader of the Parramatta people or clan. René-Primavère Lesson [1824], Voyage autour du monde … sur la corvette La Coquille, Par P. Lesson, Tome seconde, Paris: Arthus Bertrand,1839, 276

[2] Writing in 1828, the Reverend Charles Pleydell Neale Wilton, who had been Master of the Female Orphan School at Parramatta and chaplain at St. Anne’s Church, Ryde , referred to ‘Harry alias Corrangie, Chief of Parramatta’. CPN Wilton, Australian Quarterly Journal of Theology, Literature, and Science, Sydney, 1828, 233

[3] Barron Field (ed.), Geographical Memoirs on New South Wales, By various hands … London: John Murray, 1825, 438

[4] Dr Joseph Paul Gaimard of the French expedition commanded by Louis De Freycinet visited Governor Macquarie at Parramatta in November 1819, where he examined ‘Aré’ (Harry) among others, and recorded his age as 32, and his pulse rate as 87 beats per minute. Gaimard also recorded all of the physical measurements of Harry’s wife ‘Karangaran’ (Carangarang). Louis de Freycinet, Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de, Arago, Jacques, 1790-1855, Quoy, Jean René Constant, 1790-1869, Gaimard, Paul, 1793-1858, Pellion, Alphonse et al. Voyage autour du monde : entrepris par ordre du roi ... exécuté sur les corvettes de S.M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820. Paris: Chez Pillet Aîné, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1824, vol 2, 1837: 716 and 'Table No. 2: Dimensions of Various Parts of the Body of a Native Woman of Port Jackson', vol 2, 1837: 710

[5] ‘Reverend Samuel Marsden’s report to Archdeacon Scott on the Aborigines of New South Wales, 2 December 1826’, in Niel Gunson (ed.), Australian Reminiscences and Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, vol 2, Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 347

[6] ‘Curious and Interesting Account of the Original Natives of New South Wales, including particularly Botany Bay, Port Jackson &c. with the Disposition, Manners, Customs, and Habits, of the Wonderful Inhabitants of that part of the Globe. Communicated by James Thompson, Esq. &c. through the Medium of Mr. George Ryley, of the London Road, St. Georges Field’, in William Granger (ed.) The New Wonderful Museum, and Extraordinary Magazine … Volume 2, London : Printed by J. Haddon ... for Hogg and Co 1804

[8] Macarthur, William 'A few Memoranda Respecting the Aboriginal Natives' undated manuscript, Macarthur Family - Papers, 1796-1945 [Second Collection], X. MISCELLANEOUS PAPERS, 1823-1945, MS A4360, CY Reel 248, 61-67, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[9] Geo. F. Macarthur, ’Native nomenclature’, To the Editor of the Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 3 May 1890, 13

[10] Geo. F. Macarthur, ‘Native nomenclature’, To the Editor of the Herald, Sydney Morning Herald, 6 May 1890, 4

[11] Baron Charles von Hügel, New Holland Journal, November 1833-October 1834. Translated and edited by Dymphna Clark, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press/Miegunyah, 1994

[12] See Keith Vincent Smith, ‘Bennelong’s letter expresses authentic Aboriginal voice’, The Australian, Sydney, 29 December 2012

[13] Governor Lachlan Macquarie, Journal, Reel 6065; 4/1798, p 45, State Records NSW

[14] Governor Lachlan Macquarie, Journal, 7 May, 1816, MS A773, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales

[15] Governor Lachlan Macquarie, Memorandum, 29 December 1816, DL Doc 132, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales

[7] John Heaviside Clark, Field sports &c. &c. of the native inhabitants of New South Wales : with ten plates by the author , London: Edward Orme, 1813 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1423876/

[16] Dr Joseph Paul Gaimard of the French expedition commanded by Louis De Freycinet visited Governor Macquarie at Parramatta in November 1819, where he examined ‘Aré’ (Harry) among others, and recorded his age as 32, and his pulse rate as 87 beats per minute. Gaimard also recorded all of the physical measurements of Harry’s wife ‘Karangaran’ (Carangarang). Louis de Freycinet, Freycinet, Louis Claude Desaulses de, Arago, Jacques, 1790-1855, Quoy, Jean René Constant, 1790-1869, Gaimard, Paul, 1793-1858, Pellion, Alphonse et al. Voyage autour du monde : entrepris par ordre du roi ... exécuté sur les corvettes de S.M. l'Uranie et la Physicienne, pendant les années 1817, 1818, 1819 et 1820. Paris: Chez Pillet Aîné, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1824, vol 2, 1837: 716 and 'Table No. 2: Dimensions of Various Parts of the Body of a Native Woman of Port Jackson', vol 2, 1837: 710

[17] Allen Francis Gardiner, Letters from the South Seas written during the years 1821–1822, Sydney Cove, 1 August 1821, ML MSS 8112, pp 47–50, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW

[18] In 1819 the brewer James Squire, of Kissing Point (Putney), placed a classified advertisement for Harry’s benefit in the Sydney Gazette. “FOUND, by a Native (Black Harry), near the Parramatta River, on Charity Point, a PIT SAW. The above Saw is left in my Possession; and the Owner may have it by describing Marks and paying Expences.—If not claimed in 14 Days from this Date, it will be Sold for the Benefit of Black Harry. May 20, 1819” James Squire Sydney Gazette, 22 May 1819, 4; An anonymous writer in Fuller’s Cumberland Year Book (1882) referred to ‘The last aboriginal king of Kissing Point, “King Harry”’Anon, Fuller’s Rural Cumberland Year Book, 1882, 122. This appears to be a reprint of a letter headed ‘HARRY, the KING of Kissing Point’‘ that appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, 17 July 1880,p7, with the author identified as ‘M’. ‘M’ may be George Fairfowl Macarthur. Thus is an unreliable account and there appears to be some conflation with John Lang's (mostly spurious) story of Bungaree that was published in Dickens's 'All the Year Round' in 1859.

[19] Krankie (1st) was another name for Harry’s wife Carangarang, recorded as ‘One Old Woman named Cranky’, said to be 60 years of age, when she was included in the 1837 ‘Return of Aboriginal Natives’ issue of government blankets at Brisbane Water in Broken Bay. Krankie (2nd) was Carangaray, son of Carangarang and her first husband Yuwarry

[20] John Piper, Petition of the Natives at Point Piper to Governor Brisbane &c. &c., July 1822, Colonial Secretary, Reel 6052, 4/1753, 159, State Records New South Wales

[21] Barron Field (ed.), Appendix to Geographical Memoirs on New South Wales, By various hands … London: John Murray, 1825, 438

[22] ‘1793: A Song of the Natives of New South Wales’, Electronic British Library Journal, 2011 http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2011articles/article14.html

[23] Police Reports, Parramatta, Sydney Gazette, 9 January 1827, 3a

[24] Sydney Gazette, 6 July 1837, 3

[25] Macarthur, William 'A few Memoranda Respecting the Aboriginal Natives' undated manuscript, Macarthur Family - Papers, 1796-1945 [Second Collection], X. MISCELLANEOUS PAPERS, 1823-1945, MS A4360, CY Reel 248, 61-67, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales