The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Miles Franklin

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Miles Franklin

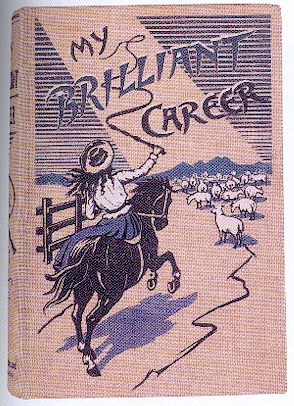

[media]The life of Miles Franklin is a vital chapter in the story of Australian literature. Even though she was never able to replicate her first great success, My Brilliant Career (1901), she continued to write influential and prize-winning texts until her death. For much of Franklin’s life she — while always a girl from the bush — called Sydney home.

Beginning in the bush

[media]Stella Maria Sarah Miles Franklin was born on 14 October 1879 at the Talbingo homestead belonging to her maternal grandmother, near Tumut, in rural New South Wales. She was known to her family as ‘Stella’, but since her first major publication, to her readers she has always been 'Miles’.[1]

Historian Jill Roe described Franklin’s mother, Susannah, as ‘a well-regulated and rather humourless person’ and her father, John, as a ‘native-born bushman [with] a touch of poetry in his make-up’.[2] The family lived at Brindabella station on the western edge of present-day Canberra, approximately 110 kilometres from Talbingo. In May 1889, the Franklin family moved to a smaller property named Stillwater. This property was near Bangalore, a railway stop that was not very far from Goulburn.[3]

In 1903, Franklin made her first move to Sydney to live with her parents, at Penrith, where they had taken up, in another down-sizing, a small land-holding.[4] Her second published novel, Some Everyday Folk and Dawn (1909) was set here. Franklin’s deep love for the bush remained with her, and is reflected in many of her fiction and non-fiction works.

Diversions around the world

In 1906, Franklin arrived in Chicago. She remained in the United States until 1915, working from 1908 for the National Women’s Trade Union League. It was pioneering and exciting work with a group of talented women who remained correspondents and lifelong friends; these friends would often be referred to as her ‘congenials.’[5]

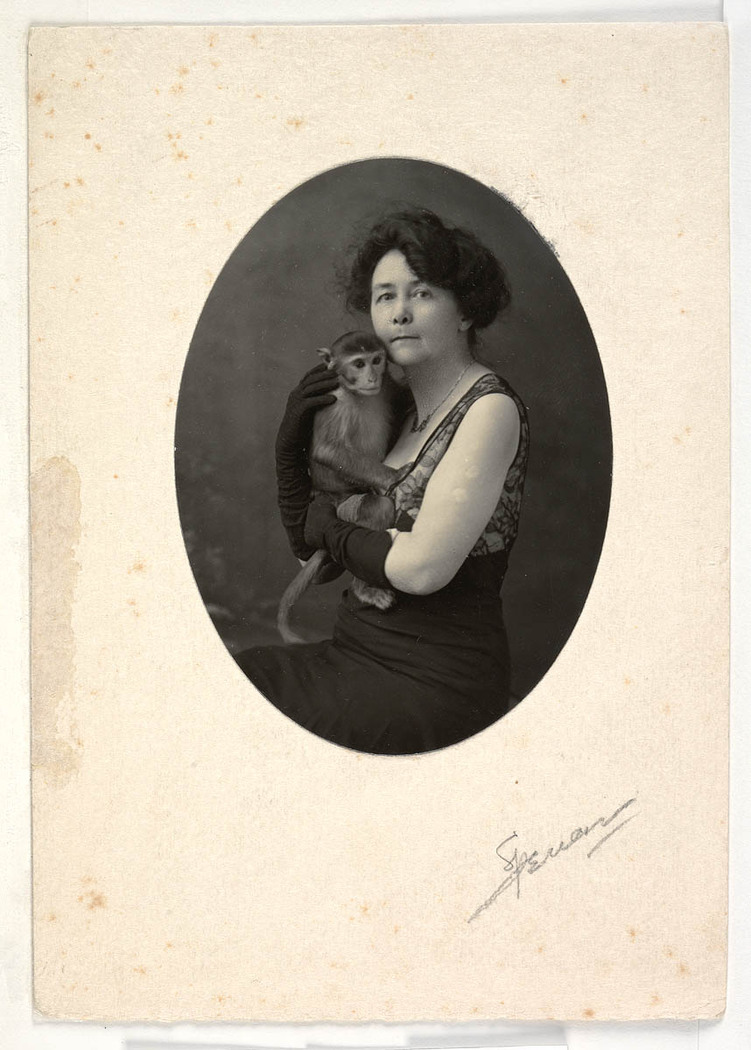

[media]In 1915, Franklin arrived in London. She secured work as a cook and earned a little bit of money from her writing. In March 1917, Franklin decided to volunteer for war work with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service. She served as a cook in a 200-bed tent hospital attached to the Serbian army near Lake Ostrovo, Macedonia, Greece, from July 1917 to February 1918.[6]

From 1918 to 1926, she was secretary at the National Housing and Town Planning Association in London. Franklin continued to identify very strongly as being Australian, but stayed in England, except for visits to Ireland in 1919 and 1926 and a visit to Australia in 1923–24, until 1932.[7]

Return to Sydney

[media]In November 1932, Franklin returned to Australia. She would live for the rest of her life in a rather modest residence at 26 Grey Street in the Sydney suburb of Carlton. The weatherboard Federation cottage had been her parents’ home since 1914. It is very likely that Franklin had helped to secure the property for her parents as she had sent her mother £105, an extraordinary sum at the time, in early 1914 (the property costing £510), while her mother sent her a house plan with a note stating: ‘I am quite satisfied, hope you are'.[8]

Franklin’s father, John, had died, in 1931 and she cared for her mother, Susannah, until she died, in 1938. The passing of each parent was hard on Franklin: she missed her father’s love and near-constant support, but her relationship with her mother was often unsettled.[9] Susannah quite possibly implied that for all the fuss that had been made of Miles, she was a failure as a daughter, especially an oldest daughter, and what is more, the only daughter to survive. Susannah certainly made it clear that she was not overly impressed by Miles’ literary output.[10]

Despite this disapproval and some disappointments, Franklin never relinquished her dreams to be a writer and to support Australian writing. On her return to Australia in the early 1930s, Franklin plunged herself into the local literary scene, standing up for a type of literature that had a ‘bias, offensively Australian’, as her friend Joseph Furphy had advocated.[11]

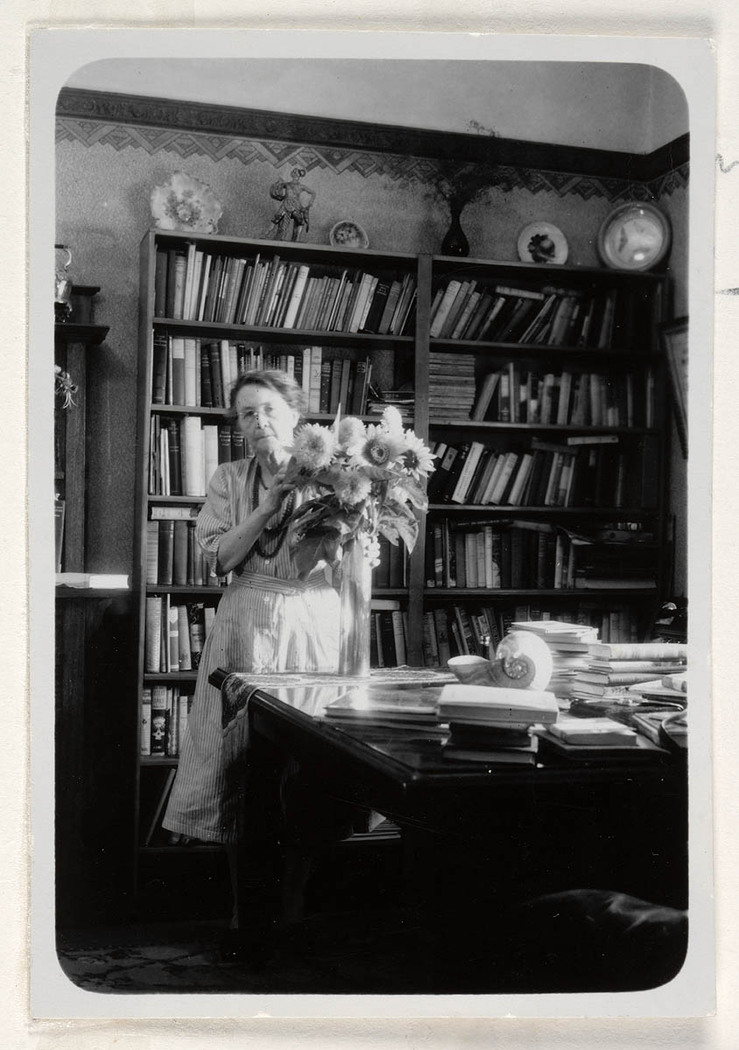

[media]Franklin passionately believed that great literature was firmly rooted in the culture of the writer. In all of her writings, in all of her oratory at meetings and on the radio, she actively promoted what she believed to be an urgent need for Australians to write ‘as Australian’. She wanted writers to reject the ideas of cultural cringe and to embrace the country that she loved so much through literature. Some of her strongest arguments for a distinctly Australian literature can be found in her work on a series of lectures she had delivered at the University of Western Australia — where she had been appointed as a Special Lecturer in Australian Literature for 1950 [12] — which were published posthumously as Laughter, Not for a Cage by Angus & Robertson in 1956.

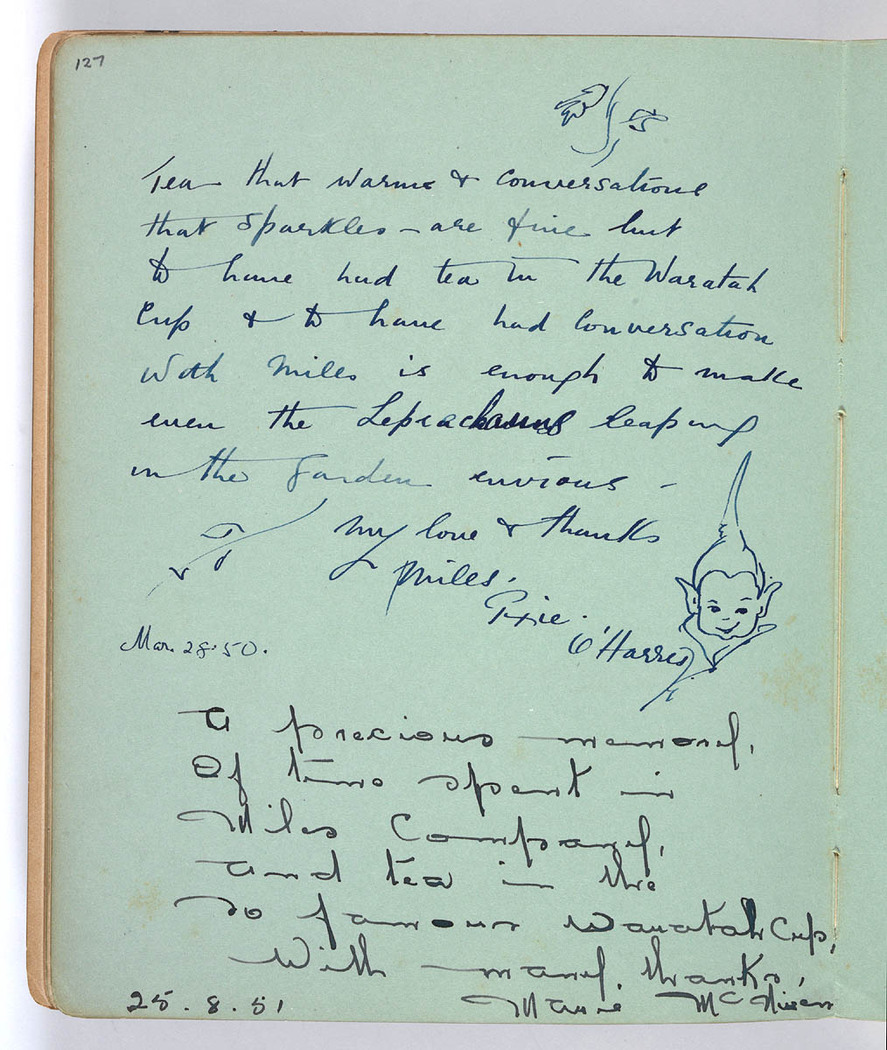

The waratah cup

[media]Franklin was a much sought-after companion for her wit and vibrant personality. She enjoyed entertaining friends at Carlton, a busy household that, at its peak, received seventy visitors over just two months. Special guests would have a ceremonial cup of tea from the ‘waratah cup’ — a great honour despite some nerves about dropping the cup — and sign the ‘waratah book’.[13]

[media]Franklin referred to her home in Sydney’s Carlton as ‘my humpy’. She was, on occasion, encouraged to move but if she was not content with suburban life, she never admitted it. As she let one friend know: ‘I have plenty of food, a good roof and bed’. [14]

At rest in Jounama Creek

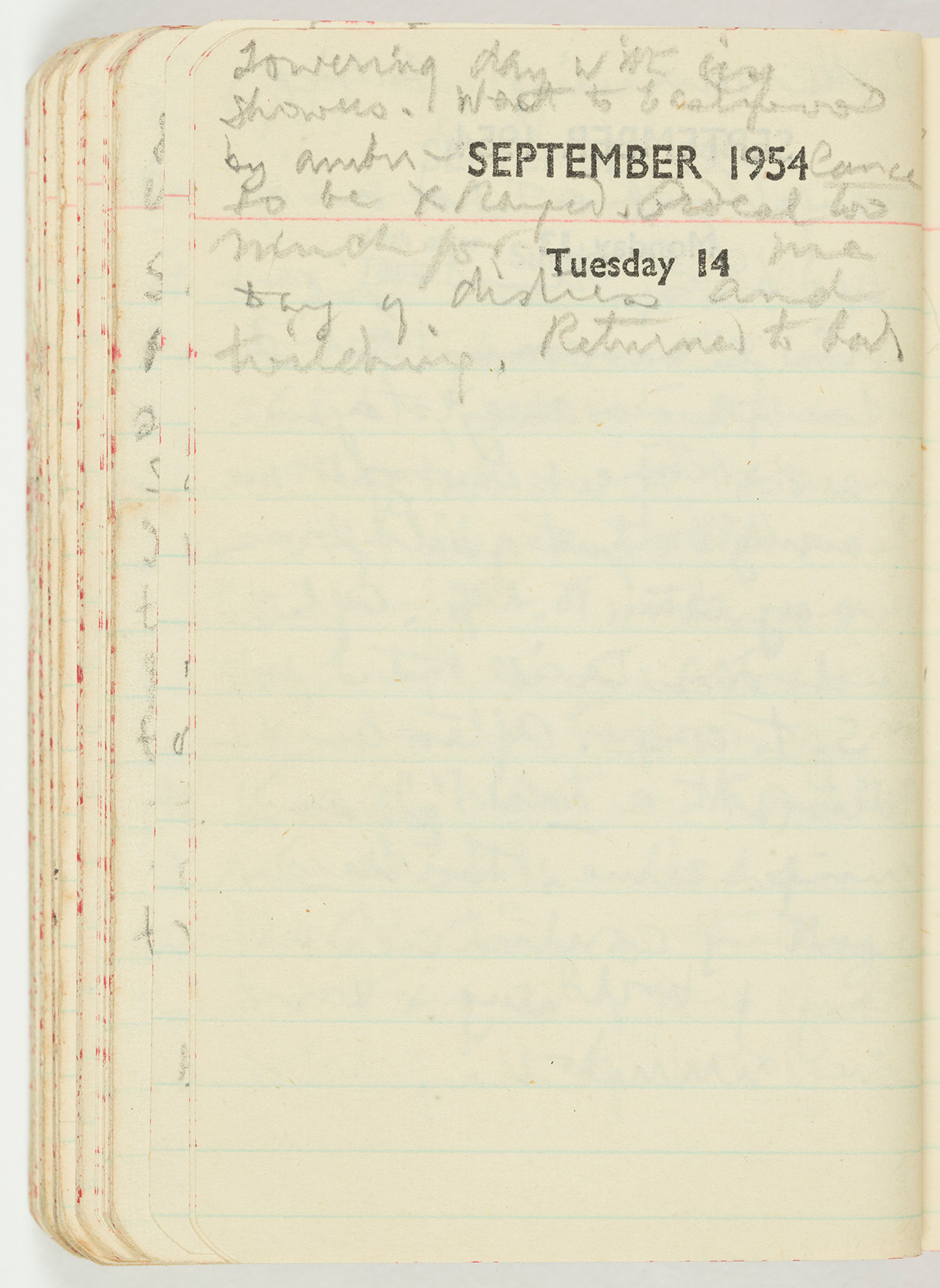

[media]Franklin suffered from poor health throughout much of her adult life and in 1954, her health declined rapidly. Shortly before her death, she moved in with her cousin Thelma Perryman who lived in the Sydney suburb of Beecroft.[15] Her pocket diaries, held with the very impressive collection of Franklin Papers at the State Library of New South Wales, give us great insights into this complicated woman. Franklin’s final diary entry, written on 14 September, reveals a heartbreaking end for a writer of so many great accomplishments: ‘Went to Eastwood by ambulance to be Xrayed’, she wrote ‘Ordeal too much for me. Day of distress & twitching. Returned to bed.’[16]

She died just a few days later, in the Seacombe Private Hospital at Drummoyne, on 19 September 1954.[17]

Having spent over two decades in Sydney, Franklin finally returned to the beautiful bush setting where she had been born. Her ashes were scattered, as was her wish, in Jounama Creek, Talbingo.[18]

The scale and scope of Franklin’s influence on her family and friends, fellow writers and the generations of Australians who have read her work, is extraordinary. Today, she is most commonly associated with the prestigious prize that bears her name: the Miles Franklin Literary Award, facilitated by a generous gift in Franklin’s will and first presented in 1957.[19] Franklin’s life was dominated by frustrations, but ‘hers was a very brilliant career.’[20]

References

Miles Franklin, My Brilliant Career, Edinburgh: William Blackwood & Sons, 1901

Miles Franklin, Childhood at Brindabella: My First Ten Years, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1963

Miles Franklin, Pocket Diaries, Unpublished, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Call no.: MLMSS 364 / Box 2 / Items 1-47, 1909–1954

Miles Franklin, Laughter, Not for a Cage: Notes on Australian Writing with Biographical Emphasis on the Struggles, Function, and Achievements of the Novel in Three Half-centuries, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1956

Rachel Franks, ‘Home at Last: Miles Franklin’s Missing Diary has Finally Joined her Collection’ in SL Magazine, Winter, 2018, pp12–13

Rachel Franks, ‘Miles Franklin’ in Stories, Sydney: State Library of New South Wales, 2018, online https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/miles-franklin

Jill Roe, My Congenials: Miles Franklin and Friends in Letters, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, [21] 2010

Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008

Notes

[1] Rachel Franks, ‘Home at Last: Miles Franklin’s Missing Diary has Finally Joined her Collection’ in SL Magazine, Winter, 2018, pp12–13

[2] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp7, 2

[3] Miles Franklin, Childhood at Brindabella: My First Ten Years, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1963; Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp27–29

[4] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p88

[5] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp128, 190; Jill Roe, My Congenials: Miles Franklin and Friends in Letters, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, [21] 2010

[6] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp197–220

[7] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp224, 285; Jill Roe, ‘Franklin, Stella Maria Sarah Miles (1879–1954)’ in National Dictionary of Biography, 1981, online

[8] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p185

[9] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, pp319, 382–83

[10] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p383

[11] Joseph Furphy in James Wieland, Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, 2nd Ed, Eugene Benson and L.W. Conolly (Eds), London: Routledge, [1994]2005, p557

[12] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p482

[13] Rachel Franks, ‘Miles Franklin’ in Stories, Sydney: State Library of New South Wales, 2018, online; Miles Franklin, Waratah Cup and Saucer, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Call no.: SAFE / R230(a-b), c.1923; Miles Franklin, The Book of the Waratah Cup, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Call no.: SAFE / R230c, 1902–1908, 1944–1954

[14] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p336

[15] Rachel Franks, ‘Home at Last: Miles Franklin’s Missing Diary has Finally Joined her Collection’ in SL Magazine, Winter, 2018, pp12–13

[16] Miles Franklin, Pocket Diaries, Unpublished, Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, Call no.: MLMSS 364 / Box 2 / Items 1-47, 1909–1954

[17] Jill Roe, Stella Miles Franklin: A Biography, Sydney: Fourth Estate, 2008, p555

[18] Rachel Franks, ‘Miles Franklin’ in Stories, Sydney: State Library of New South Wales website, 2018, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/miles-franklin viewed 2 April 2020

[19] The first recipient of the Miles Franklin Literary Award was Patrick White for his novel Voss (1957)

[20] Rachel Franks, ‘Miles Franklin’ in Stories, Sydney: State Library of New South Wales website, 2018, https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/stories/miles-franklin viewed 2 April 2020