The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

William H Bennett

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

William H Bennett

Being transported beyond the seas may well have been a blessing in disguise for William H Bennett. A labourer in his homeland, Bennett received what was then considered a light sentence of seven years transportation to New South Wales. There he progressed from being a convict in the 'town gang' at Parramatta to one of the town's eminent bakers, 'carrying on business on a large scale.' [1] He also became a full-fledged settler as legal titleholder of considerable land including well-situated adjoining allotments on O'Connell Street containing his home and business. His social circle was comprised of equally ambitious and high achieving emancipists such as the chief constable of Sydney as well as other notable characters. His colonial life exemplifies the opportunities that existed in the young colony for skilled or astute emancipists to make a better life for themselves than they may have had in their native lands.

Early life in England

Born circa 1786 in England, Bennett's native place was recorded on his certificate of freedom in 1824 as Bath, Somerset, in South West England. [2] Since no baptism record has been discovered to date, and Bennett had a very common name, his parentage is unclear. This is muddied further by the many alternate and/or inaccurate spellings of his second given name in official documents and newspapers, as well as his headstone at St John's Cemetery which reads 'Havvard.' However, in a memorandum on a land grant written by Governor Gipps, the governor himself appears to identify 'Harrard' as the correct spelling and ordered that the error be rectified on the legal grant. [3]

Gipps's fastidiousness may provide us with a significant piece of evidence of Bennett's origins, as it was a common practice in Britain to use the maternal maiden name as a second given name. This opens up the possibility that Bennett was the son of Hannah Harrard and William Bennett who married at St Giles, Camberwell in Southwark, London, on 14 August 1780 and were recorded as being 'of the parish.' [4] While this South East England location places Bennett's parents outside of his recorded birthplace of Bath, we know that in adulthood Bennett was in London, in the parish of Lambeth, Surrey – not far from where Harrard and Bennett wed at Camberwell. In Lambeth, at roughly thirty-one years of age in 1817, with dark brown hair, hazel eyes, a 'fair ruddy' complexion and standing at 5 feet 8 inches, [5] Bennett was employed as a labourer. [6] These scanty details of Bennett's pre-colonial existence and Bennett himself would have passed into obscurity had he not wound up in Surrey County Gaol.

Crime and punishment

On 20 October 1817, Bennett appeared before the magistrates RJ Chambers Esq and T Fish Esq at the Surrey Quarter Sessions at Newington charged with theft [7] upon the property of Charles Clark, a gentleman of Walcot Place, Lambeth. Clark accused Bennett and a second man, Charles Hall, also a labourer, 'with wilfully breaking open his dwelling house…no person being therein, and feloniously stealing therefrom, a lamp and other articles, his property.' [8] Bennett and Hall were tried together, both pleading not guilty. However, with four accusers [9] the men were found guilty of 'theft or intent to steal' and sentenced to seven years transportation. [10]

Though they shared an occupation, crime, trial, and conviction, henceforth Hall and Bennett appear to have lived separate lives in the colony. [11] Hall had a considerably easier journey from England; transported to New South Wales on the Isabella on 3 April 1818, he disembarked five months later on 14 September 1818 and was assigned to work as a labourer at Windsor, west of Sydney. [12] He was then sent (more than once) north to Newcastle on the Lady Nelson and the Elizabeth Henrietta before being assigned to a Sydney-based master. [13] Bennett, by contrast, was transported with 199 other male convicts on the Tottenham on Sunday 11 January 1818 from Sheerness, North Kent. Two false starts saw the Tottenham turn back and go to Spithead and Plymouth for repairs where more than thirty of the convicts on board opportunistically tried to 'effect their escape' by attempting to remove their leg irons.' [14] Following these setbacks, the Tottenham successfully departed with all prisoners accounted for on 17 April 1818 and arrived in New South Wales on 14 October 1818, less ten prisoners who had died of scurvy [15] during the very long voyage. [16]

Life on the chain gang

Four days after his arrival, and a year to the day after his conviction, Bennett and eleven of his fellow Tottenham prisoners were assigned to Richard Rouse's 'Town Gang' in Parramatta. [17] As a member of a government work gang, Bennett would have repaired town roads and buildings. One public building Bennett likely worked on was the Colonial Hospital, as Rouse was overseeing its construction in 1818. Bennett would have performed this hard labour in coarse clothing [18] and may have even been forced to work in leg irons. He certainly would have witnessed – and maybe even received – floggings, as town gangs laboured under close supervision and were reportedly 'very cruelly and tyrannically treated.' [19]

A new life

After almost two years in the colony, Bennett began laying a foundation for a new life. His early efforts in this regard included choosing a wife – a challenge since men greatly outnumbered women and convicts were required to apply to the governor for permission to marry. On 3 July 1820, having found a suitable mate, Bennett sought approval to wed twenty-six year old Elizabeth Agnes Miller, a convict who had been in the colony a mere two months, having arrived on the convict ship the Janus on 3 May. [20] Miller's daughter, Rebecca, had likewise journeyed aboard the Janus as a free passenger at the tender age of six. [21] Undoubtedly, the need to provide shelter and security for young Rebecca was an incentive for Miller to make a speedy marriage. Bennett appears to have wholly embraced his role as a stepfather to Rebecca for, twelve years later, he brought a court case against a young publican who left his stepdaughter a jilted bride. [22] Bennett and wife Elizabeth went on to have at least two children together. [23] Elizabeth Ann was born in 1829 and William H Bennett Jnr, in 1831. Incidentally, Bennett Jnr inherited his father's second given name and its misspellings. [24]

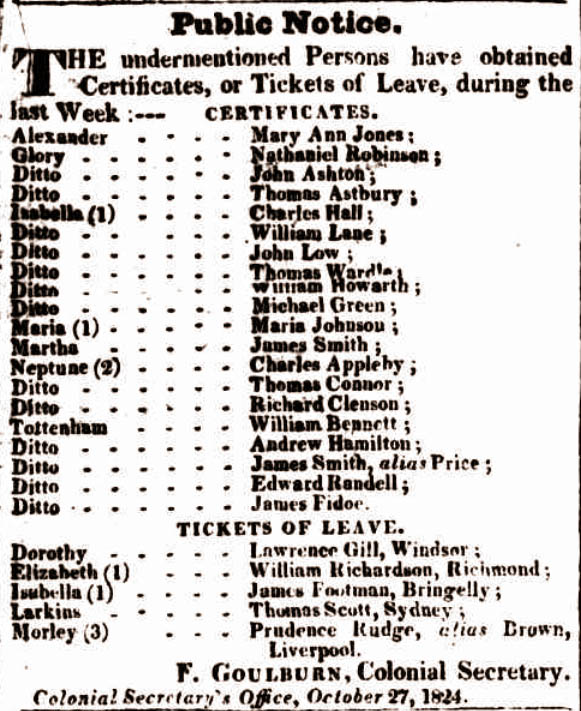

[media]Bennett received his ticket of leave in or before 1822 and with the extra freedom this afforded him – namely the ability to work for himself – Bennett commenced his new life as a baker. In September of 1824, Bennett showed his solidarity with other convicts by signing his name to recommend favourable consideration be given to fellow convict Daniel Jackson's petition for a ticket of leave. [25] The following month Bennett received his own certificate of freedom declaring his sentence had been served in full on 21 October 1824, seven years and one day after his conviction. [26]

The advertisement in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser for the sale of Mr Patrick Kirk's Parramatta property on the corner of O'Connell and Hunter streets in August and September of 1824 was therefore most opportune. The newly freed Bennett had presumably amassed funds since obtaining his ticket of leave a number of years earlier, enabling him to purchase this property. It boasted 'every requisite accommodation,' including 'a substantial dwelling house, replete with every convenience,...seven rooms, a four-stall stable, stock-yard, a well of good water, and an excellent garden, well stocked with fruit-trees, &c.' [27] It was at this location that Bennett established his successful bakery and family residence.

[media]Eventually Bennett held title for all the O'Connell Street land from Hunter to Macquarie streets which contained the three (now heritage-listed) Georgian cottages later known as the Travellers' Rest. [28] In 1828, with his business growing, Bennett began to build a larger purpose-built bakery on the corner of O’Connell and Macquarie streets and had two convicts, Charles Stephens and John Davis, privately assigned to work for him as bakers. By 1841, the number of convicts assigned to him rose to three. [29] In addition to his Parramatta property where he had three horses, the 1828 census reveals Bennett also had a farm in Windsor with three horses and two horned cattle. [30]

Bennett's achievements in business and as a settler allowed his children to be educated alongside individuals who became some of Old Parramatta's most distinguished residents, and also enabled them to 'marry well. [31] Although his convict history precluded him from ever being one of the 'Exclusives,' Bennett's new station in life as a highly respectable baker' [32] and landholder confirmed his place in a category of upwardly mobile emancipists who had managed to negotiate their way through the degradations of the convict system without losing sight of the opportunities the colony offered. And with his mixture of humble beginnings and high achievements, Bennett was comfortable fostering close ties with like-minded high-achieving former felons like the Chief Constable of Sydney, George Jilks, [33] and just as accepting of an eccentric street character dedicated to 'pedestrianism' called 'The Flying Pieman,' who was a regular guest for weeks at a time in Bennett Snr's abode on the corner of O'Connell and Hunter streets. [34]

Bennett [media]passed away 'June 3 1860, aged 74 years, at his O'Connell Street residence,' [35] thirteen years after the death of wife Elizabeth. [36] He was buried in the same plot as Elizabeth at St John's Cemetery, Parramatta, and just a few minutes' walk up the street from where he had lived and worked for almost half of his outstanding life. [37]

References

Ancestry.com

Ballyn, Susan. 'Brutality Versus Common Sense: The 'Mutiny Ships,' the Tottenham and the Chapman,' in Landscapes of Exile: Once Perilous, Now Safe, edited by Anna Haebich and Baden Offord. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2008, 31–42.

Convicts Transported. Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the United Kingdom. Class: HO 11, Piece 3.

Dunn, Judith. The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John's. Parramatta: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991.

Anna Haebich and Baden Offord. Eds. Landscapes of Exile: Once Perilous, Now Safe. Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2008.

Notes

[1] Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3.

[2] Bennett's certificate of freedom was issued 21 October 1824. Register of Certificates of Freedom (Certificates of Emancipation), 5 Feb 1810–26 Aug 1814 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series Number: NRS 12208; Archive Roll: 601

[3] Registers of Land Grants and Leases (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series Number: NRS 13836; Item: 7/481A; Reel: 2702

[4] Register of Marriages (Saint Giles, Camberwell: London Metropolitan Archives) P73/GIS, Item 013

[5] These particulars were recorded on his certificate of freedom, issued October 21, 1824. Register of Certificates of Freedom (Certificates of Emancipation), 5 Feb 1810–26 Aug 1814 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series Number: NRS 12208; Archive Roll: 601

[6] His occupation, parish and county were recorded in the transcript of his trial; Surrey Quarter Sessions, 1780–1820 (Surrey: Surrey History Trust, United Kingdom), Category: Institutions & Organisations: Record Collection: Courts & Legal, Trial Date: 20 October 1817

[7] Surrey Quarter Sessions, 1780–1820 (Surrey: Surrey History Trust, United Kingdom; Musters and Other Papers Relating to Convict Ships (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series: CGS 1155, Reels: 2417–2428s

[8] Surrey Quarter Sessions, 1780–1820 (Surrey: Surrey History Trust, United Kingdom), Category: Institutions & Organisations: Record Collection: Courts & Legal, Trial Date: October 20 1817

[9] Witnesses included Clark and his servant, Miss Sarah Fryer, two watchmen in Lambeth Walk known as William Speness and his employee John Simpson, and another two upstanding witnesses, Alexander Sheafe Burkitt of 8 Canterbury Place and constable William Wyld of the Bell public house–Bennett and Hall.

[10] Surrey Quarter Sessions, 1780–1820, (Surrey: Surrey History Trust, United Kingdom), Category: Institutions & Organisations: Record Collection: Courts & Legal, Trial Date: October 20 1817

[11] As noted later in this entry, Bennett did end up with a farm at Windsor, so it is possible that they would have interacted again, but at this stage there is not any direct evidence to support this.

[12] Hall's distribution in Windsor; see Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 58, Series: NRS 937, Item: 4/3499, Reels 6004–6016

[13] Hall's transportation to Newcastle 1 February 1819 see Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 295, Series: NRS 937, Item: 4/3499, Reels 6004 and again on July 11 1821, see Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 149, Series: NRS 937, Item: 4/3504, Reels 6004-6016; Hall's assignment to Sydney master, David Reid, on 5 January 1824, see Special Bundles, 1794–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 57, Series: NRS 898, Reels: 6020–6040, 6070, Fiche 3260–3312

[14] One of these aspiring escapees succeeded and swam 'from Barnpool to Mount Edgecumbe,' The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany, Volume 5, January to June 1818 (London: Black, Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen, 1818), 517–8

[15] See Tottenham's surgeon Robert Armstrong's medical journal, cited in Susan Ballyn, 'Brutality Versus Common Sense: The 'Mutiny Ships,' the Tottenham and the Chapman,' in Anna Haebich and Baden Offord, (eds), Landscapes of Exile: Once Perilous, Now Safe (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2008), 40

[16] In addition to 42 cases of scurvy recorded on the voyage, there had been 22 cases of catarrh and 28 of diarrhoea while 32 suffered from fever and 26 battled with pneumonia, among other things. See Tottenham's surgeon Robert Armstrong's medical journal, cited in Susan Ballyn, 'Brutality Versus Common Sense: The 'Mutiny Ships,' the Tottenham and the Chapman,' in Anna Haebich and Baden Offord, (eds), Landscapes of Exile: Once Perilous, Now Safe (Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2008), 40–1

[17] Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 110, Series: NRS 937, Item: 4/3499, Reels 6004–6016

[18] The exact characteristics of convict clothing are difficult to determine for the period in which Bennett served his seven-year sentence. Information regarding convict dress is contradictory in the late 1810s and early 1820s chiefly because it was when more distinctive clothing was being made but was only haphazardly introduced in early attempts to create order and control in an ever-increasing convict population. See Margaret Maynard, Fashioned from Penury: Dress as Cultural Practice in Colonial Australia (Cambridge, Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 14–21

[19] 'The Good Old Days,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 17 December 1904, 11

[20] Copies of Letters Sent Within the Colony, 1814–1825 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia: State Records Authority of New South Wales), 107, Series: NRS 937, Item: 4/3502; Convicts Transported (Kew, Surrey, England: The National Archives of the United Kingdom), Class: HO 11, Piece 3

[21] 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), 65, Parramatta Series: NRS 1273, Reel: 2507

[22] 'Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3

[23] There may have been more than two, but this is the number the author has been able to verify to date.

[24] Alternate spellings for Bennett Jnr. include Howard and Harvard.

[25] Petitions to the Governor from Convicts for Mitigations of Sentences (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), 61b, Series: NRS 900, Item: 4/1872

[26] Register of Certificates of Freedom (Certificates of Emancipation), 5 Feb 1810–26 Aug 1814 (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), Series Number: NRS 12208; Archive Roll: 601. See also the listing of William Bennett as recipient of his certificate of freedom in 'Public Notice,' The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 28 October 1824, 1

[27] 'Advertising: To be SOLD,' The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 12 August 1824,1

[28] 'Travellers Rest Inn Group,' State Heritage Register, NSW Environment & Heritage website, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/heritageapp/ViewHeritageItemDetails.aspx?ID=5051404, viewed 5 June 2014

[29] 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), 65, Parramatta Series: NRS 1273, Reel: 2507; 1841 Census: Householders' Returns and Affidavit Forms (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), 45, CGS 1281, Reels 2508–2509

[30] 1828 Census: Householders' Returns (Kingswood, New South Wales, Australia, State Records Authority of New South Wales), 66, Parramatta Series: NRS 1273, Reel: 2507

[31] 'An Old Parramatta Native. Born in 1831,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 31 March 1906, 8; 'Obituary: Mr. W. H. Bennett,' Molong Express and Western District Advertiser, Saturday 6 July 1907, 9

[32] Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3

[33] Supreme Court: Breach of Promise of Marriage: Miller V. Brett,' Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thursday 21 June 1832, 3

[34] 'An Old Parramatta Native. Born in 1831,' Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, Saturday 31 March 1906, 8

[35] 'Family Notices: DEATHS,' Empire, Monday 4 June 1860, 1; 'Family Notices: FUNERAL,' Empire, Monday 4 June 1860, 8

[36] 'Family Notices: DIED,' The Sydney Morning Herald, Wednesday 20 October 1847, 3

[37] Buried in Section 2, Row F of St. John's Cemetery, Parramatta. Judith Dunn, The Parramatta Cemeteries: St. John's (Parramatta: Parramatta and District Historical Society, 1991), 109; Michael Brookhouse, Photograph of Bennett and Bennett's sandstone altar with inscription, Australian Cemeteries Index, http://austcemindex.com/inscription.php?id=8629750, viewed 18 August 2014