The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Irish Famine Memorial, Hyde Park Barracks

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Irish Famine Memorial, Hyde Park Barracks

Henry George Grey entered the British parliament in 1826 and, in 1830, when his father became Prime Minister, he became Under-Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. He was a member of a group of colonial reformers, including Edward Gibbon Wakefield, who shared views on land and emigration, advocating that the colonies be governed for their own benefit and not the mother country. In 1846, during the Famine in Ireland (1845–1852), he was appointed Colonial Secretary. These positions gave him charge of Britain's colonial possessions, including Australia.

New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia wanted increased expenditure to assist immigration and reluctantly Grey permitted some borrowing. [1] At the same time the a select committee of the New South Wales Legislative Council recommended the introduction of labour, emphasising the need for female domestic servants and even acquiring some of them from 'female orphan institutions'. [2]

Caroline Chisholm, the 'emigrant's friend', philanthropist and protector of female emigrants declared herself in favour of such a scheme. It was Earl Grey's responsibility and came to be known as Earl Grey's pauper immigration scheme. With his approval, and with the cooperation of the Poor Law Guardians in Ireland, between October 1848 and August 1850 the Colonial Land and Emigration Commissioners brought 4,412 young women from the workhouses in Ireland to New South Wales, Port Phillip and Adelaide, 2,220 of whom arrived in Sydney. [3]

The workhouse women

[media]Post-Famine Irish immigration to Australia was very significant, with estimates that over 30,000 single Irish women arrived over a 15-year period between 1848 and 1863. In a male-dominated society, the Irish workhouse women altered the demographics of Australia in a very significant way with 11 shiploads arriving in a three-year period. On 6 October 1848 the Earl Grey was the first ship to arrive in Sydney with female orphans and was followed by the Panama, Thomas Arbuthnot, Inchinnan, Lady Peel, William & Mary, Lismoyne, Digby, John Knox, Maria and Tippoo Saib. After volunteering for emigration, all potential emigrants were carefully inspected by the Poor Law Guardians in Ireland, and their literacy, health and previous employment record examined before embarkation. This process was far more vigorous than for other applicants for assisted passage from Ireland.

[media]On arrival they were housed for protection in the Hyde Park Barracks, from where they were hired out. The process was supervised by the Sydney Orphan Immigration Committee, and legal employment indentures were drawn up between the Committee and each individual employer. [4] For example, Jane Ann (Aimie) Stewart was 17, a Presbyterian from Belfast who could read. She was employed by a veterinary surgeon in York Street, Sydney at £10 a year. When her employer moved his family to Keira Vale, near Wollongong, Jane Ann went with them. She married in the southern highlands, moved to Wauchope and eventually settled in the north coast of New South Wales. [5] Like Jane Ann Stewart, a large number of women on the Earl Grey, the first ship to Sydney, were initially employed in Sydney and then moved to the country or were sent to country immigration depots in Goulburn, Bathurst or other far-flung parts of the colonies such as Moreton Bay (Brisbane).

Some made their lifelong homes in Sydney, often after a time working in the country. Honora Hogan, was a 16-year-old Catholic house servant from Mitchellstown, County Cork. She was sent to Maitland as an invalid suitable only for general housework. By November 1852 she returned to Sydney where she married at St Philip's Church of England. Unable to have children, perhaps because of deprivations during her adolescent years in Ireland during the Famine, she and her husband raised an 'adopted' daughter who had 10 children in Sydney. Despite her inability to read or write, Honora, with the help and support of her husband, William Harvie Holmes, sponsored her mother and sisters as emigrants from Ireland to Sydney, rescuing them from the Famine. Her sister, Bridget arrived on the Glen Isla in July 1857, her mother and two other sisters arrived per Abyssinian in September 1859. Many families in Sydney can trace their families to Honora. [6]

While the memory of the Famine in Ireland may have long lingered in the psyche of the Irish people who survived it, it was little spoken of in Australia until the sesquicentenary approached in the 1990s, when visitors from the Commemoration Department of the Irish Government visited Australia.

Commemoration as a moral act

In March 1995, the President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, visited Sydney. Her left-of-centre politics, her strong commitment to human rights and her concern and compassion for victims of the Famine endeared her to many, particularly the Irish-Australian community. She called on this community to mark the memory of the Great Famine in some special way, just as she had done at Grosse -Ile, Quebec, in August 1994 when she said

The Great Irish Famine Commemoration is a moral act because it is a part of the shaping of us in our sense of Irishness. We are shaped with that dark time. [7]

In 1996 the Irish Government brought a 45-piece orchestra from Ireland to Australia to launch Dr Charles Lennon's composition 'Famine Suite'. Concerts were organised in Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne. The concerts ran simultaneously with conferences on the Famine and left a legacy of information about the Famine and those who immigrated to Australia as a result of An Ghorta Mor.

Tom Power was [media]Chairman of the Tipperary Association in Sydney in the 1990s. A long-term resident of Australia, he was born in Clonmel, Tipperary, on the Waterford border. He was motivated by Mary Robinson's call and with the help of many Irish-born supporters he formed a committee to raise funds, and select a statue (as they thought at the time) and a place to erect it. Richard O'Brien, the Irish Ambassador to Australia at the time, was a passionate supporter. He was an eloquent and entertaining speaker whose understanding of commemorating the Great Famine differed from that of the rank and file in the Sydney Irish community. He said,

it is appropriate that Irish people and those of Irish descent everywhere should rescue the Famine dead from the oblivion of that awful time. [8]

Creating the monument

At a meeting of the Irish County associations in November 1995, Tom Power was elected chairman of a Committee to erect a monument. The project time was 12 months but it was almost four years before it was unveiled. After much work and with the cooperation of the Historic Houses Trust, particularly Mr Lynn Collins, Curator of the Hyde Park Barracks at the time, New South Wales Premier Bob Carr, the Irish Government, the Australian Government, the descendants of the workhouse orphans and interested members of the Irish and Australian community, fundraising began. It was often against some very strong public objection as certain sectors of the community objected to 'commemoration of Famine'. Tom Power recalled,

nasty phone calls from the public telling us 'leave Queen's Square alone and try our luck in the bush'. Another phone caller asked if this was an Irish joke, 'erecting a memorial to people who had died 150 years ago'. Others, including high profile members of our own Irish Community suggested that any money raised would be better spent on the living than the dead. [9]

After much deliberation three possible locations for the sculpture were suggested. One location was the forecourt of the Hyde Park Barracks and the second was the southern wall. In this debate there was a right and a left wing faction. The left was in favour of the forecourt while the right would not hear of it. Pressure was also mounting from some people in the Irish community who insisted the committee get on with the building as the project was taking up too much time. Finally, due to this and other outside influences including phone calls, the forecourt location was abandoned. It seemed that the sight of a Famine orphan would be too confronting to Queen Victoria on the opposite side and to others as well. After much discussion with City of Sydney Council employees and the Council's art advisor, it was agreed that artists would be invited to respond only to the southern wall.

Tenders were called for the design of a memorial, and from 160 requests for the tender brief, 41 serious tenders were submitted from all over the world. Finally, on 4 December 1997, the design of Hossein Valamamesh, himself an immigrant from Iran, and Angela Valamamesh, was chosen. By then the budget had risen to $200,000, though the final figure was closer to $350,000. There was still much work to be done, including securing council approval. The City of Sydney Council approved the development application in July 1998 and much politicking, and many discussions, support and objections followed, along with the construction.

The artists' vision of the Sydney's Famine monument

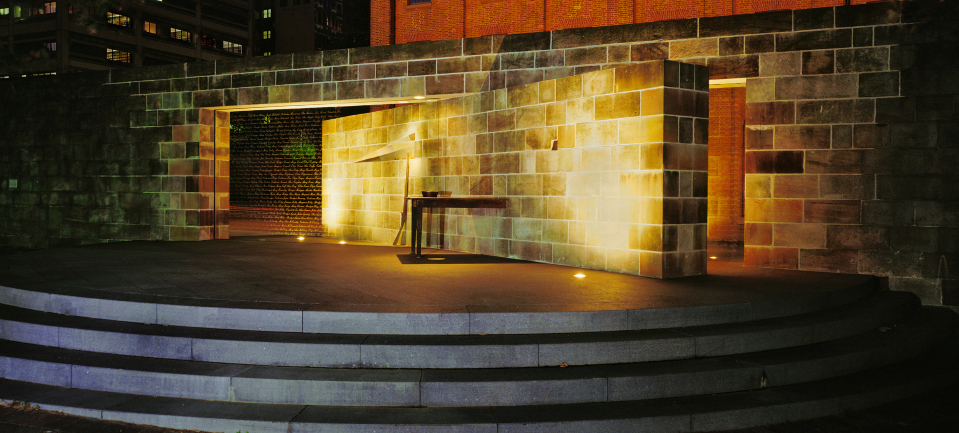

[media]The main focus of the sculpture design is the dislocation of the Barracks' southern sandstone wall. A section of this wall was dismantled and rebuilt on a rotated axis. In the space of the demolished wall two glass panels bearing sandblasted inscriptions of women's names are inscribed and a cast bronze table intersects the stone wall.

The rotated sandstone wall represents disruption and dislocation. Its rotation results in a gap which provides the viewer with a degree of visual accessibility to both sides of the art work. The effect of the observer being unable to walk through or view the work in its totality is maintained. The viewer is obliged to rely on memory in order to complete the image and make it whole.

The table, split in two, has on one end a simple bowl with a void in its base that continues through the table. At the other end is a simple institutional table setting with utensils, also cast in bronze. Although the table is divided and even dislocated by the stone wall it represents an element of continuity and a link between the two sides of both the sculpture and the lives of those who emigrated. The table and the more intimate spaces created within the rotated wall evoke the domestic nature of life and work for the majority of Irish women migrants while their simplicity and sparseness allude to the subject of Famine.

The glass walls with finely sandblasted names of women gradually fading from one side to the other indicates their large numbers and adds an ethereal quality or lightness. The faint and fading quality of the text on the glass panels also indicates the frail and inconstant nature of memory.

The other element of the work is a soundscape created by Paul Carter which is located within the courtyard's solitary lillipilli tree. Carter, a Melbourne artist and writer, noted that the soundscape was called 'Out of their feeling', indicating that as the list of the dead increased, the living were 'out of their feeling'. This meant that at a certain point the suffering had gone beyond speech. Carter and the Valamaneshes decided to locate the soundscape work in the lillipilli tree in the precincts of Hyde Park Barracks because it looks very isolated and orphaned. Carter said he 'wanted to have that small tree become as it were, a pool of silence amid all the clamour of the city traffic'. [10]

Sydney's Famine memorial opening and continuing legacy

Following a commemorative Mass at St Mary's Cathedral which was packed to overflowing, the memorial was unveiled by Sir William Deane, Governor-General of Australia, on 28 August 1999, in the presence of an estimated 2,500 people, including 800 Famine orphan descendants.

Since then, an event has been held each year on the last Sunday of August, the time of the unveiling, to keep the memory of these Famine orphan immigrants alive , to remember the million or more who died during the Famine period and, in the spirit of Mary Robinson's first call, to remember those who are victims of Famine today. These 4,412 were the survivors and the monument also recognises their contribution to the building of this country.

With the help of Irish Government's Emigrant Support Program, a website has been established to make the history of this significant emigrant event, and the stories of the Famine workhouse immigrant women, available to anyone, whether they are descendants of these women or historians in Australia, Ireland or elsewhere in the modern global Irish community.

References

Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine orphans in Australia, Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc, Melbourne, 1991 and vol 2 2001

Richard Reid, Farewell my children: Irish assisted emigration to Australia, 1848-1870, Anchor Books Australia, Spit Junction, 2011, especially chapter 6, 'The removal of mendacity from one soil to another', pp 140–71

Irish Famine Memorial Sydney website, www.irishfaminememorial.org, viewed 28 November 2012

Notes

[1] John M Ward, 'Grey, Henry George (1802–1894)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 1, 1966, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/grey-henry-george-2126/text2693, viewed 28 November 2012

[2] Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine orphans in Australia, The Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc, Melbourne, 1991, p 4

[3] Trevor McClaughlin, Barefoot and Pregnant? Irish Famine orphans in Australia, The Genealogical Society of Victoria Inc, Melbourne, 1991, p 1; Richard Reid, Farewell my children: Irish assisted emigration to Australia, 1848-1870, Anchor Books Australia, Spit Junction, 2011, p 102

[4] Richard Reid, Farewell my children: Irish assisted emigration to Australia, 1848-1870, Anchor Books Australia, Spit Junction, 2011, pp 143–48

[5] Details from R Hughes, descendant, in 2009

[6] Correspondence with descendant, Kay Sherring, 2012, see Irish Famine Memorial Sydney website, www.irishFaminememorial.org.au, under Honora Hogan from Mitchellstown, County Cork, per John Knox

[7] From notes of lecture by Tom Power, Galong Conference, 5 October 2008

[8] Ambassador Richard O'Brien, speech supporting proposal to erect the Memorial, 10 March 1998, from notes of lecture by Tom Power, Galong Conference, 5 October 2008

[9] Reminiscences and notes of lecture by Tom Power, Galong Conference, 5 October 2008

[10] Vision of the artists, Hossein and Angela Valmanesh, tender document June 1998

.