The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Manly Cove, Kai'ymay

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Manly Cove/Kai'ymay

Kai'ymay, or Manly Cove, a sandy cove on North Harbour on the western side of the Manly peninsula, is a key site of the earliest contacts between Aboriginal people, the Eora (this is the local word meaning 'people') and the British people who arrived on the First Fleet in 1788. It continued to be the place to which Governor Phillip and his officers returned in their attempts to open communications with Aboriginal people – sometimes by force. It was also where Aboriginal people took action against the newcomers in their land – Governor Phillip was speared here by an Aboriginal warrior in September 1790, an event that ultimately led to the first reconciliation between Aboriginal people and white settlers in Australian history. A number of the early Sydney paintings depict Manly Cove and these key moments in cross-cultural contact as they unfolded on the beach.

Aboriginal Kai'ymay

The name of the Aboriginal clan of Kai'ymay is not known for certain. It may have been Kai'ymaygal, or Gayamaygal, for in the Sydney language, the suffix 'gal' was usually added to the place name to indicate the people of that place. But these people may have been Cameragal, or closely associated with them. The Cameragal were the people of the north shore of Sydney Harbour, a dominant group, famous for their strength, authority and the skills of their karajdi (doctors). Certainly the admiring comments of the First Fleet officers on the physique of the Kai'ymay warriors suggest they may have been from the same clan. [1]

However, it is important to note that Aboriginal social structure and territorial boundaries were much more complex than simply groups of people with a single name 'belonging' to one specific, clearly bounded area. Aboriginal people had multiple identities, names and affiliations through ancestry, birth and marriage relationships. While each clan was associated with a particular area, the smaller family bands had access to different country through family and marriage connections. Paul Irish has identified much larger cycles of movement as well, which he calls the 'affiliated coastal zone', a series of interlinked areas reaching from Port Stephens in the north to Shoalhaven on the south coast. [2] Kai'ymay lay in this zone – in fact a well-marked pathway literally led from here north along the peninsula to Pittwater on Broken Bay. [3]

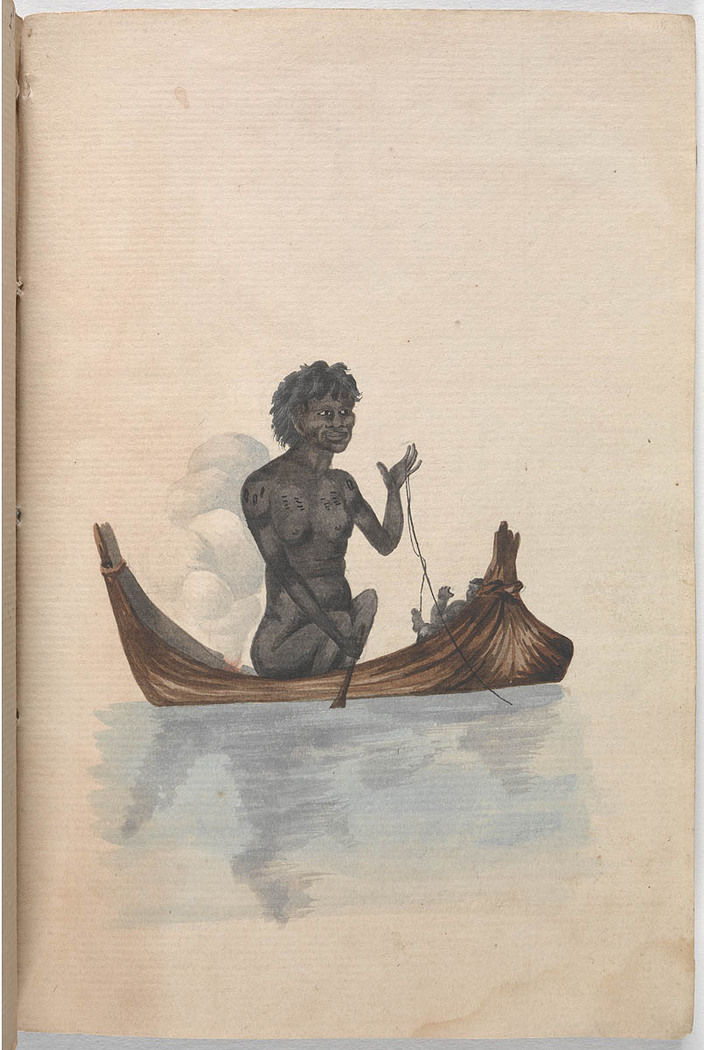

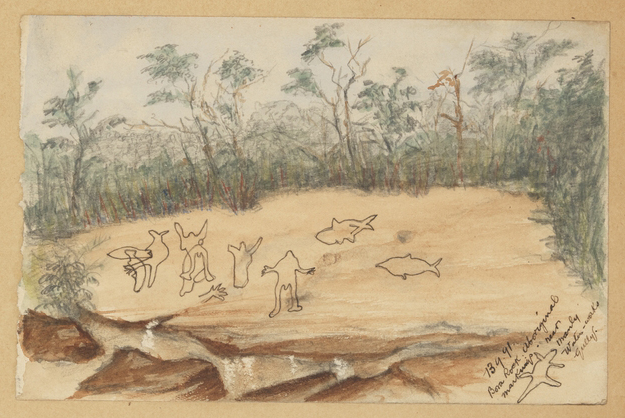

[media]Like the other coastal groups, the Cameragal were saltwater people, reliant on the sea and harbour for a diet of fish and shellfish, as well as seabirds. They were at home on the waters as well as on land. The women especially were skilled canoeists and fisherwomen, paddling and fishing from bark nowie with their children and babies, and a small fire on a clay pad to cook the catch. [4] The sandstone country of the Manly region provided rock platforms and walls for art works and is still richly endowed with rock carvings depicting people, implements, birds, animals and fish, as well as grinding grooves for making and sharpening axes and other tools. Sharp stone (basalt, silcrete) for weapons and tools was imported from inland quarries and rivers, while spears and fishgigs (callarr and mooting) were also tipped with shell. [5] As in other parts of Australia, the Cameragal used fire to keep the country clear, to attract animals to new grass and make root vegetables easier to find. The early officers witnessed these blazes, and observed that they were lit on windy days. [6] And here, as elsewhere, society was ordered by Aboriginal law, which revolved around payback: the guilty person stood trial by spear. In 2005, the remains of a warrior were found at nearby Narrabeen – the first archaeological evidence of death by spearing in Australia. This man died over 3,600 years ago from spear wounds – the stone barbs are still embedded in his spine – and an axe wound to his head. [7]

[media]The later nineteenth-century history of the Aboriginal people of the Manly area is not yet clear – there were reportedly camps in the area from the 1850s until at least 1881, when a number of Aboriginal people from Manly were persuaded by the Reverend Daniel Matthews to join his Aboriginal mission at Maloga. Given the slow rate of development in the area, it is likely that Aboriginal presence here was continuous at least until that time, and very likely longer. [8]

The British arrive

The settler name Manly Cove originated from the first encounter of the people of Kai'ymay with the British officers and sailors in January 1788. Disappointed and concerned by the lack of fresh water and exposure to the winds at Botany Bay, Governor Phillip took a boat to explore Port Jackson, a harbour to the north, seen by James Cook on his 1770 voyage. The boat nosed around the long headlands and into several coves, looking for building land and freshwater streams, and the strangers were struck by both the beauty and the utility of the harbour. When they approached Kai'ymay in the north arm, they saw a group of 20 strong men wading out towards their boat. These men took the gifts offered and were curious about the boats, inspecting them closely. Phillip and the officers were impressed. They expected Aboriginal people to be as Cook and Joseph Banks had described them – weak, timid, cowardly and 'incurious'. These men were just the opposite. Phillip later wrote that he named the place 'Manly' for their admirable manly qualities. [9]

[media]But the new name was not fixed – or not yet. Shortly after that first encounter, as well as other friendly encounters in the lower harbour area, Kai'ymay was the site of the first meeting with Aboriginal women. On most other occasions, the Eora warriors had kept the women and children well out of sight – the British thought this was probably another sign of their gallant 'manliness'. But they still asked constantly to meet the women, proffering gifts of beads and trinkets. On another visit to Manly Cove on January 29, they negotiated with an elder, and finally some of the younger women came forward. They stood by the boats trembling and laughing as the white men reached over to drape them with strings of buttons and beads. The English officers described them as 'naked beauties', who were 'perhaps, inseparable from the female character in its rudest state'. So they renamed Manly Cove: it became Eve's Cove. [10] But it seems that neither name was much used at first. People referred to the area more casually as 'down the harbour' or 'North Arm'. Manly Cove did not come into use until after the story of Phillip's renaming was published in The Voyage of Governor Arthur Phillip to Botany Bay in November 1789. [11]

Manly Cove encounters

Phillip was instructed to treat 'the natives' with 'kindness', and to live with them in 'peace and amity'. [12] He took these instructions seriously. One reason he may have chosen the snug Sydney Cove – Warrane – for the settlement was that it was the one place in the harbour where there were no warriors shouting from the ridges or wading out to meet the boats, as at Manly Cove. But after the early meetings on the beaches, the Eora promptly shut down communication and avoided the strangers and their camp in Warrane/Sydney Cove altogether. In fact the British felt they were being quarantined there. Skirmishes increased when they ventured into the surrounding areas and, in May 1788, two convicts were killed by warriors. Eleven months after arriving, Phillip still had little clue of the Eora's numbers, or their intentions. After an Eora attack on the convict brickmakers at the Brickfields (near present-day Central Station), he resorted to kidnapping an Aboriginal man in the hope of forcing open a means of communication. His target area was Manly Cove. Phillip wanted one of the superior 'manly' warriors, someone from the group with whom they had established such good relations in those earliest days. The kidnapping from the beach was violent and distressing. The captive man remained silent, so they called him Manly, only later discovering his name: Arabanoo. [13]

Arabanoo was a dignified and gentle man who refused to play the role of cross-cultural envoy. He was kept a prisoner in Sydney, and after the outbreak of the terrible smallpox epidemic among the Eora in April 1789, he nursed his stricken countrymen in Sydney's hospital. He contracted the disease himself and died on 18 May 1789.

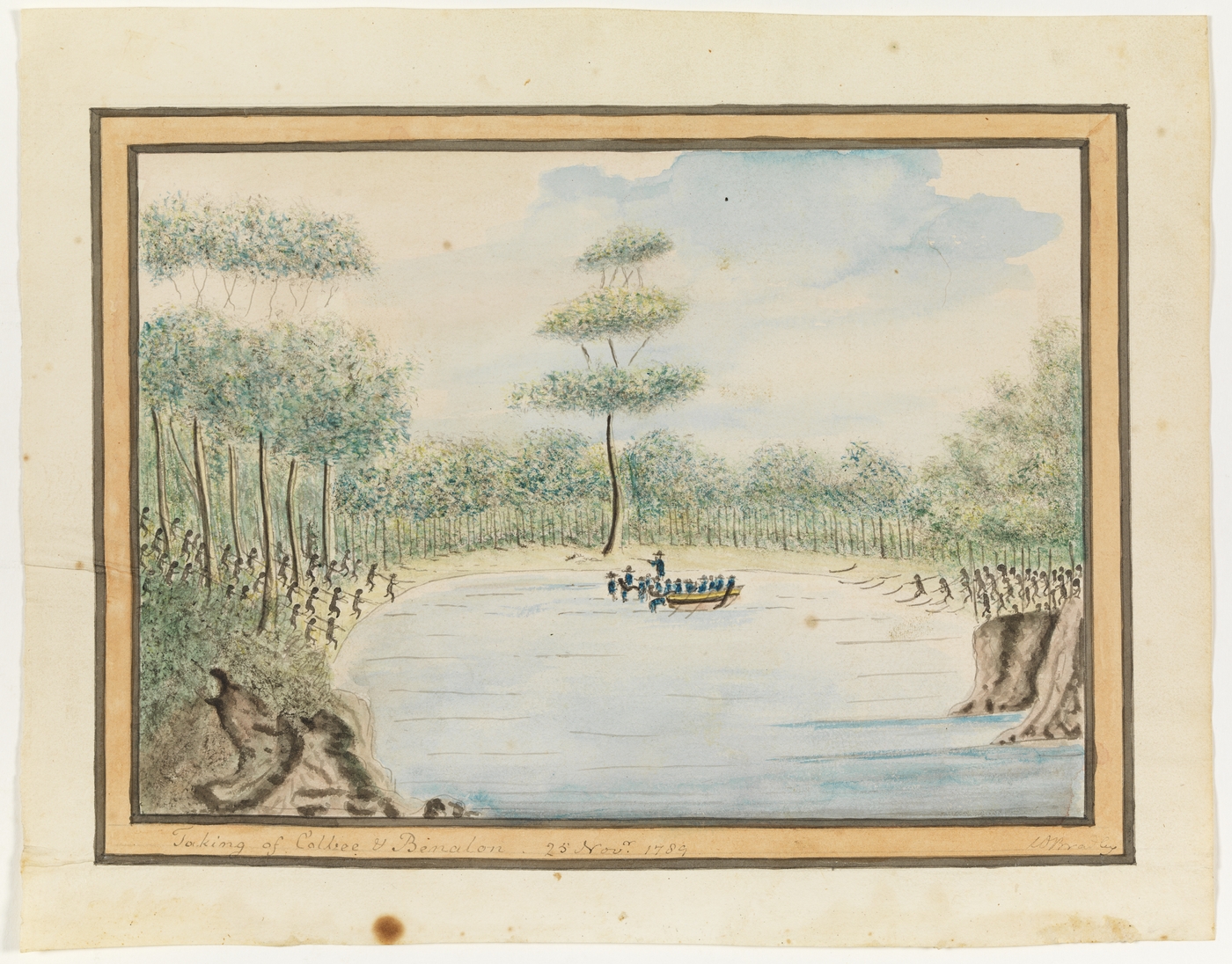

Cross-cultural [media]relations soon deteriorated and in November Phillip once more sent the boats out to kidnap warriors. Again they rowed down the harbour to the beach at Manly Cove, violently abducting two men. This time they returned with Coleby, a Cadigal man from the south shore of Sydney Harbour, and Woollarawarre Bennelong, of the Wangal of the south shore of Parramatta River. Ironically neither was from the 'manly' clan of Kia'ymay as Phillip had clearly intended. Coleby soon escaped from Sydney, but Bennelong remained, and proved enthusiastically receptive to learning all about the British, their language, resources and intentions. He and Phillip became friends and often walked out together, but after seven months, Bennelong escaped too. Phillip and the officers were devastated – another hopeful cross-cultural experiment had failed. They rowed up and down the harbour, calling Bennelong's name. The Eora fisherwomen mimicked them in their higher voices. [14]

Four months later, in September 1790, a whale washed up on the beach at Manly Cove and a large number of Eora gathered for a great whale feast. Bennelong summoned Phillip to attend by sending him a packet of whale meat, and an invitation, and Phillip hurried over in a boat to meet his old friend. It was a happy reunion there on the sand of the cove, with gift giving and conversation, Bennelong asking after his old Sydney friends and toasting 'the King' with a glass of wine, as he had done during his time at Government House. But suddenly Bennelong disappeared and a circle of warriors began to close in on Phillip. A stranger, a man named Willemering, seemed agitated and when Phillip began to approach him in his customary way, slowly, hands outspread, Willemering picked up a barbed wooden spear and hurled it at the governor with such force that it passed through his shoulder. Panic broke out. Phillip was unable to run because the spear was so long it hit the ground. A frantic Lieutenant Waterhouse eventually broke the tough spear shaft, whereupon they bundled the governor down the beach and into the boat and rowed as fast as they could back to Sydney. There the surgeons extracted the spear and pronounced the wound non-lethal. Phillip was up and about only ten days after his ordeal. [15]

Historians have long puzzled over the meaning of this dramatic event but in recent decades several have suggested that what Phillip experienced was a payback ritual. [16] In Aboriginal law the guilty must stand trial for their crimes and the crimes of their people. The encircling warriors and the spearman's actions that day on the beach at Manly Cove echo the way traditional Aboriginal law was imposed. Kai'ymay was, after all, Aboriginal land; the whites were in Aboriginal country and subject to their laws. Perhaps Phillip sensed something of this: much to his officers' confusion and frustration, he refused to retaliate.

As a result, instead of the outbreak of violence and war the officers feared, peace was made between the two groups. Good relations were re-established through meetings, gifting and dancing, and Bennelong finally agreed to come into Sydney with his wife Barangaroo and their friends in November 1790. The officers were delighted. Finally, a lasting peace with the Eora had been achieved. [17]

Manly Cove today

Today most of Manly Cove has been developed. Every half-hour, the ferries at the big wharf release shoals of tourists and day-trippers, to wander along the broad concrete esplanade, the Corso lined with busy shops and pubs, the high rise beyond. A stone monument erected in 1928 stands above the cove, commemorating the arrival of 'the first white man', Arthur Phillip, in 1788. A second plaque corrects the first, admitting that Phillip didn't actually set foot in Manly Cove on that first occasion. A third, added in 2006, remembers Phillip's spearing by Willemering, and a fourth celebrates the Olympians and Paralympians of the Sydney 2000 Games. Apart from Willemering, no mention is made of Aboriginal people. But the beach still arcs round the cove and looking southwest from the sand you can still see the bush-clad slopes of Dobroyd Head. When the First Fleet people first saw Manly Cove, that is what it looked like too. This was the site for first encounters between people from opposite sides of the globe, the site of greeting, gift-giving and dancing, of goodwill and curiosity, as well as betrayal, violence, justice and retribution. From a world history perspective, it was also the site where the two great waves of migration from Europe to Asia and Australia, separated by over 90,000 years, were reconnected. [18]

References

Attenbrow, Val. Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2002.

Curby, Pauline. Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly. Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001.

Karskens, Grace. The Colony: A History of Early Sydney. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009.

Vincent Smith, Keith. Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792. Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001.

Notes

[1] Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 11; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2002), 22–28, esp 25; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony of New South Wales, facs ed, vol 1 (Adelaide: Adelaide Libraries Board of South Australia, 1971), 558; Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, published as Sydney's First Four Years, ed LF Fitzhardinge (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1979), 285

[2] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2002), 22–28, esp 25; Paul Irish, 'Hidden in Plain View: Nineteenth Century Aboriginal People and Places in Coastal Sydney', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 2014, pp. 57-59

[3] See Alan M Dash, 'Phillip's Exploration of the Hawkesbury River', in Hawkesbury River History: Governor Phillip, Exploration and Early Settlement, eds Jocelyn Powell and Lorraine Banks (Sydney: Dharug and Lower Hawkesbury Historical Society, 2000), 11–30. See also 'A Map of the hitherto explored country, contiguous to Port Jackson, laid down from actual survey', J Walker, engraver, 1791 or 1792, reproduced in Paul Ashton and Duncan Waterson, Sydney Takes Shape: A History in Maps (Brisbane: Hema Maps Pty Ltd, 2000), 11

[4] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 38–40, 401–21

[5] Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 11; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records (Sydney: University of New South Wales Press, 2002), 120–4; and see Peter Stanbury and John Clegg, A Field Guide to Aboriginal Rock Engravings (Sydney: Sydney University Press, 1990). A fishgig is a multi-pronged spear used for spearing fish.

[6] See George Worgan and John Hunter, 1788, cited in Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 15–16 and notes 282

[7] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 443–6; Josephine J McDonald, Denise Donlon, Judith H Field, Richard LK Fullagar, Joan Brenner Coltrain, Peter Mitchell and Mark Rawson, 'The First Archaeological Evidence for Death by Spearing in Australia', Antiquity, 81 (2007): 877–85

[8] Paul Irish, 'Hidden in Plain View: Nineteenth Century Aboriginal People and Places in Coastal Sydney', PhD thesis, University of New South Wales, 2014, 194, 198, 207, 222–23

[9] Arthur Phillip, cited in Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 9–10; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 52

[10] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 52–4. Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 20. Eve's Cove was inscribed on the earliest known map of Port Jackson, an anonymous copy of John Hunter's Chart of Port Jackson, New South Wales, Survey'd Feby 1788 (Watling Collection, Natural History Museum, LS3), see Art of the First Fleet and Other Early Australian Drawings, eds Bernard Smith and Alwyne Wheeler (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 73

[11] Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly (Manly: Headland Press/Manly Council, 2001), 10

[12] Governor Phillip's Instructions, 17 April 1787, Historical Records of Australia, series 1, 1:13–14

[13] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001), 23–38; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 351–78

[14] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001), 39–48; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 378–83

[15] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001), 51–9; Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 383–5; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2003), 110–32

[16] See Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2003), 110–32; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001), 51–9; William Stanner, 'The History of Indifference Thus Begins', Aboriginal History, 1 (1977): 2–26

[17] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 386–92; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers (Melbourne: Text Publishing, 2003), 133–40; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (Sydney: Kangaroo Press, 2001), 60–71

[18] Tom Griffiths, 'Ecology and Empire: Towards an Australian History of the World', in Ecology and Empire: Environmental History of Settler Societies, eds Tom Griffiths and Libby Robin (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1997), pp. 3-4