The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Archibald Prize

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Controversy and delight all round

For years, sundry po-faced critics and pundits have declared the genteel art of portrait painting dead and redundant but, against all the odds, the art remains alive, well and flourishing in Australia thanks to the Archibald Prize. Nonetheless, it remains an art event that still attracts the opprobrium of critics who maintain a steadfast opposition to the Archibald Prize and a deep suspicion of its value to either Australian art or the community at large. I beg to differ on both counts. This prize – which now galvanizes public opinion and interest and attracts inevitable controversy across the country like no other art event – was established in 1919 in the will of the late Mr J F Archibald, an eccentric, indeed acerbic, individual who was born in Geelong in Victoria in 1856 and given the names John Feltham. [1]

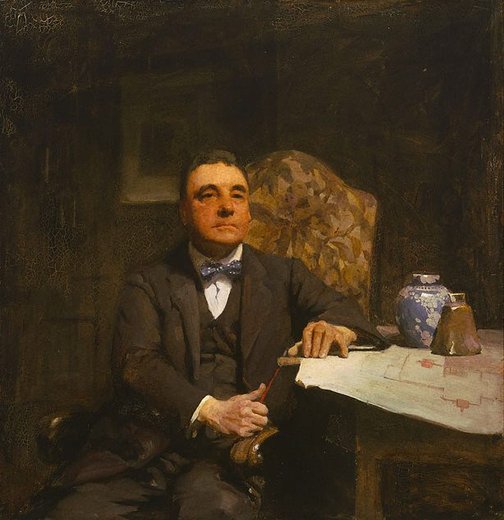

JF Archibald

[media]Life for Archibald was not all plain sailing. An ambitious, progressive, nationalistic and aspiring journalist, in 1880, he launched the weekly news journal, The Bulletin . Renowned for its strident patriotism, with writers like Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson, the journal struggled in its early years and ran into financial difficulties that resulted in Archibald's imprisonment for failing to pay damages after losing a libel case. After his release he travelled to England, returning to Sydney fired-up with enthusiasm for his republican ideals. The Bulletin then flourished and when Archibald died in 1919, he did so a relatively wealthy man.

Perhaps as a sign of his republican views, he left in his will a bequest to the trustees of the Art Gallery of New South Wales (then known as the National Art Gallery of New South Wales) of one-tenth of his estate for the establishment of an annual prize to be judged by the Trustees. [2] With regard to the prize, the relevant clause in his will reads:

…to the trustees of the New South Wales National Gallery to provide an annual prize to be styled The Archibald Prize for the best portrait preferentially of some man or woman distinguished in arts letters science or politics painted by any artist resident in Australia during the 12 months preceding the date fixed… [3]

Of our place and time

There are two crucial conditions in this clause in Archibald's will that have, I believe, ensured the prize's tenacious longevity and success. Firstly, that the prize was to be judged not by curators, art historians, critics or other such professionals but by the members of the Board of Trustees, that is, essentially lay men or women; and secondly, that the portrait had to be painted in the 12 months leading up to the award. The subjects, therefore, were always going to be people and personalities of our place and our time. The Archibald Prize has thus become not only a great slice of Australian art history but also a fascinating glimpse into Australian social history.

[media]In accord with Archibald's wishes, among the early winners of the prize were people of some note in the worlds of arts, letters and science. The first prize in 1921 was awarded to the artist William Beckwith (Billy) McInnes (who went on to win no less than seven times) for a portrait of the Melbourne architect Harold Desbrowe Annear. However, McInnes attracted some criticism in 1924 when he won with his portrait of a certain Miss Collins, the daughter of an employee of the Victorian State Parliament, because she was not, understandably, considered to be 'distinguished in art, letters, science or politics'. The whole genre of portraiture, at least on the evidence of the Archibald Prize, in the 1920's, 30's and 40's retained a generally conservative stylistic tradition and the subjects were also generally 'worthy' sitters.

I like to compare those early winners – architects, professors, occasional politicians and state governors, writers and judges – with the current crop of Archibald sitters: fellow artists, television personalities, celebrity chefs (for heaven's sake!), a jockey (the winning subject in 1974), actors and, on the whole, an overwhelming representation of subjects from the worlds of the arts, fashion and entertainment. The Archibald really is a barometer of social progress and process.

Controversy and legal battles

The year 1943 was a watershed year in the history of the Archibald. The trustees awarded the prize to William Dobell for his portrait of fellow artist Joshua Smith. Some of the members were of a mind to resign over the decision to give the award to what was widely described as a 'caricature'; it certainly was a painting that broke from the established norm. The sitter, Joshua Smith, looked as though he was made from rubber with his attenuated neck and tentacle like arms, but of course, Dobell was moving with the times and, like all contemporary art, he was arousing controversy.

That year, in the midst of WWII, over 150,000 people flocked to see this 'caricature' posing as art. A court case ensued, initiated by fellow artists. The trustees won when, over a year later in October 1944, the presiding judge resolved that no court of law was empowered to set aside the decision of those legally appointed to judge the prize. Fair enough! That, however, was the start of the legal career of the Archibald!

Matters again came perilously close to a legal battle again in 1975 when the trustees decided to award the prize to John Bloomfield's portrait of the film maker, Tim Burstall. When pressed, the artist admitted he had made the painting from a photograph and the trustees quickly removed the prize from Bloomfield. This led to the inevitable and continuing debate about the rules, about the nature of a portrait 'from life', about the relevance of the Archibald etc. [4] However, it did not deter Bloomfield from launching a lawsuit against the trustees for the return of his prize – he lost!

The matter of interpretation cropped again in 2004 when the prize was awarded to Craig Ruddy's imposing portrait of the renowned Aboriginal dancer and actor David Gulpilil, painted, or drawn, in so-called 'mixed media'. One artist took exception, firmly claimed it was created in charcoal and graphite, was not a painting and therefore ineligible. He too went to court but he had public opinion against him for it was a popular choice and, in any event, by dint of some close observation and analysis we did in fact find just a little paint on the surface!

I must admit here that I too was sued in the cause of the Archibald prize. In 1988, a fairly large picture of the colourful stockbroker Rene Rivkin, famed for his Havana cigars and gold worry beads, was submitted. I happened to be looking at this rather overbearing painting with the sitter one day before the judging process and when asked what I thought of it replied, with abject honesty, that it bore more resemblance to a pile of chewing gum than it did to his good self. Unfortunately, that comment was overheard and appeared in the press the next day, whereupon the artist, Azerbaijan born Vladas Meskenas took, understandably I suppose, umbrage and decided to sue me.

Apparently, the sitter had agreed to buy the painting but following my observations, decided against the purchase. Eventually, we all went off to court and in spite of my considered, objective and legitimate criticism of the work in the courtroom – for example, Rene is depicted holding a cigar and, as I pointed out, nobody who smokes a Havana cigar holds it in the way shown – I was finally fined $100. Nobody has yet managed to explain the basis for this fine and I shall reserve my right to say pretty much what I think about a work of art but of course be very careful about the sitter!

During my years as director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales I have been painted for the Archibald around eight times but, with one exception, the trustees have taken one brief glance and said, firmly, 'Edmund, out'. Only once did I make it into the final exhibition, in the year 2006. I was painted by Adam Cullen who had won the prize in the year 2000 for his portrait of the actor David Wenham. The now late and lamented Adam painted me with his characteristic bravado and many would say that I ended up looking like a melting Dracula fashioned from gelato with a little tomato ketchup. I like the portrait but obviously not the trustees who favoured a most unlikely and rather macabre work titled The Paul Juraszek Monolith – After Marcus Gheeraerts (a sixteenth century Flemish illustrator and engraver) by the Melbourne artist Marcus Wills.

The Archibald Prize is an absolute institution in the Australian art calendar and an event keenly anticipated every year. It is the source of great debate, some wonderful controversies and above all an art exhibition that the public adores. Nor should we overlook that, for all the fun and widespread interest it generates, artists take it very seriously and the resources of passion, craft, imagination and talent that are invested in the hundreds of portraits submitted every year are testament to the current lively state of the art of portraiture in this country.

References

Peter Ross, Let’s Face It: The History of the Archibald Prize, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, revised edition 2005

Notes

[1] These he subsequently, at the age of 19, changed from John Feltham to Jules Francois and declared that he was the son of a French Jewish mother; all in the pursuit of providing himself with a more exotic and colourful heritage. Indeed 'born in Geelong’ changed to 'born in France’ according to his marriage certificate

[2] Incidentally, he left approximately half of his £90,000 estate to the Australian Journalists Benevolent Fund for 'the relief of distressed journalists’. There are times when I, perhaps like many others, think most journalists should be mostly distressed most of the time. His will also left funds for the commissioning, by a French sculptor, of the much-loved Archibald Fountain in Hyde Park. See Peter Ross, Let’s Face It: The History of the Archibald Prize, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, revised edition 2005, p 13

[3] "…to the Trustees of the New South Wales National Gallery to provide an annual prize to be styled "The Archibald Prize" for the best portrait of some man or woman distinguished in Art Letters Science or Politics painted by any artist resident in Australasia during the twelve months preceding the date fixed by the Trustees for sending in the Pictures…", excerpt from the will of JF Archibald, 'Last Will and Testament of Jules Francois Archibald’, 10 April 1940, archives of the library of the Art Gallery of New South Wales

[4] It all frothed up again in 1981 when a portrait of the splendid Rudy Komon by Eric Smith won and somebody mischievously found a photograph of the subject in precisely the same pose – with the ever-ebullient Rudy holding a glass of wine. However, Smith knew his sitter well

.