The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Barangaroo and the Eora Fisherwomen

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Barangaroo and the Eora fisherwomen

Barangaroo was one of the powerful figures in Sydney's early history. She was a Cameragaleon, from the country around North Harbour and Manly. The Cameragal group was the largest and most influential group in the Sydney coastal region. [1]

Barangaroo [media]was very likely present at the first meeting between the white newcomers and Cameragal women at Manly in February 1788, an event captured in William Bradley's watercolour. [2] But she was probably also among the women who tried to lure white men ashore in North Harbour in November 1788 so that the Cameragal warriors could attack them. [3]

The officers finally met Barangaroo in late 1790. They found her very striking but also a little frightening. She had presence and authority. They estimated her age at about 40, and this is significant. She was older, more mature, and possessed wisdom, status and influence far beyond the much younger women the officers knew.

By the time they met Barangaroo, the Eora world had changed. Smallpox had swept through the population and killed a disproportionate number of women and old people. But Barangaroo had survived. She was one of a reduced number of women who had the knowledge of laws, teaching and women's rituals and she exercised this authority over younger women. She had lost a husband and two children to smallpox, and she now had new younger husband: the ambitious Bennelong. [4]

While other, younger, more biddable Eora women politely agreed to put on clothes, Barangaroo refused point blank. All she ever wore was a slim bone through her nose. When the whites invited her to watch a flogging, she became disgusted and furious, and tried to grab the whip out of the flogger's hands. [5]

She was clearly unhappy about Bennelong's consorting with the whites. She was so angry with him on the first occasion he went to visit Sydney that she broke his fishing spear. Every time he tried to visit Rose Hill (Parramatta) she refused to allow it, and he wasn't permitted to go on the excursion to the Nepean River in April 1791.

Barangaroo and Bennelong were both determined and short-tempered. When he hit her, she hit him back. The officers were perplexed at this, because the couple were obviously so fond of each other and clearly delighted in one another's company. [6]

But why was Barangaroo trying to stop Bennelong's politicking and movements? Was she just a 'difficult' woman? Was she different from all the other women? [7]

[media]The answer may lie in fish and fishing.

Eora fisherwomen

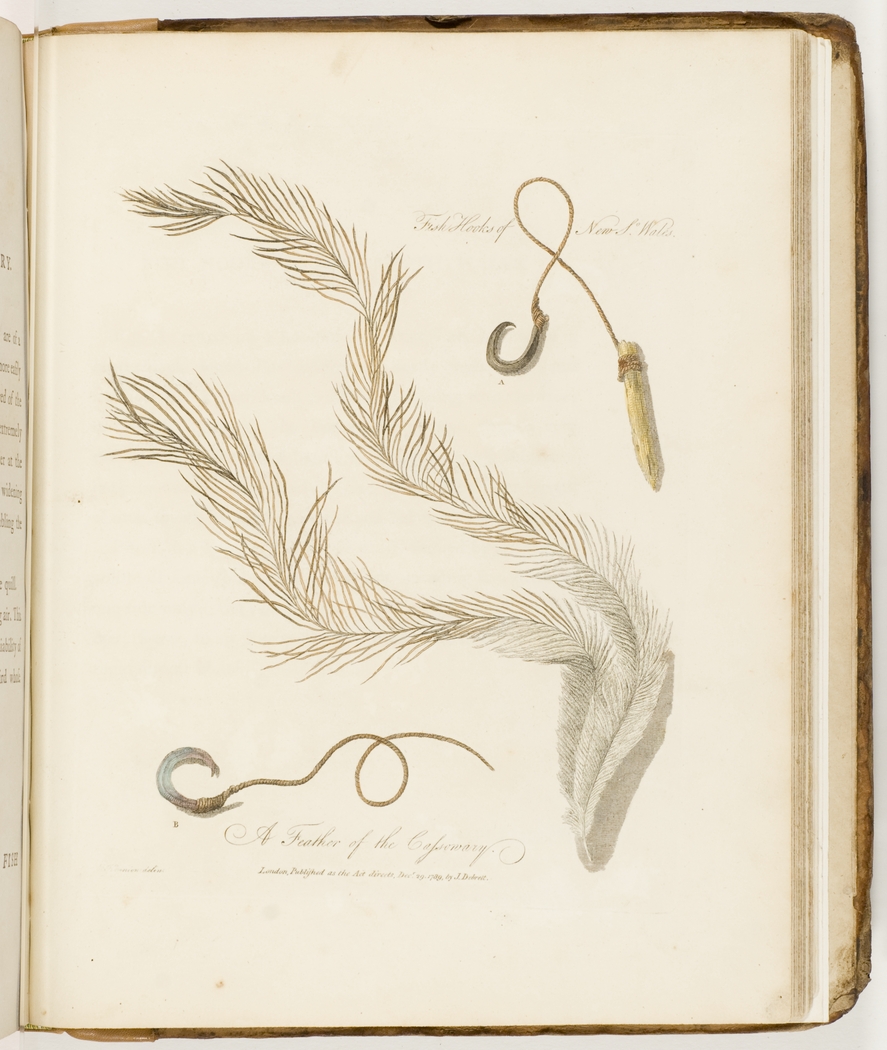

[media]Barangaroo was a fisherwoman. Eora women like her were the main food providers for their families, and the staple food source of the coastal people around Sydney was fish. Unlike men, who stood motionless in the shore and speared fish with multi-pronged spears, or fish-gigs ( callarr and mooting), the women fished from their bark canoes (nowie) with lines and hooks. They made their fishing lines (carr-e-jun) by twisting together two strands of fibre from kurrajong trees, cabbage trees or flax plants. Animal fur and grass 'nearly as fine as raw silk' were also used to make lines. One observer described them as 'nicely shredded and twisted very close and neatly'. The distinctively crescent-shaped fish hooks ( burra) were honed from the broadest part of the turban shell (Turbo torquata). [8]

[media]These hooks were beautiful, and the lines well-made – First Fleet Surgeon George Worgan thought that they showed 'the greatest ingenuity' of all the Eora implements. Sometimes the women wore them around their necks like a necklace. But they were not decorative objects. They were Eora women's working tools and implements, essential for survival, and closely associated with their identities and power. The British officers quickly learned to respect the value of women's fishing gear – these were not female frippery, 'trifling things in a fishing way', but serious and important, like men's spears and clubs. [media]The officers started collecting the hooks as well as spears and fish-gigs. Convicts caught stealing fishing tackle were severely punished. [9]

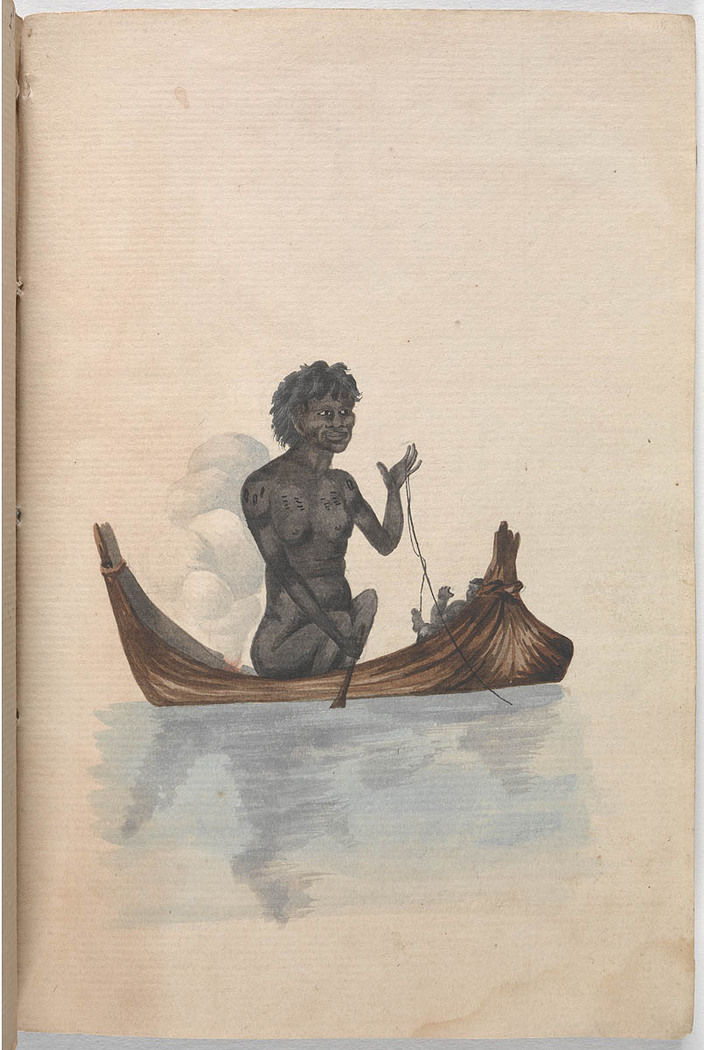

Eora women's [media]skills in fishing, swimming, diving and canoeing were extraordinary. The women skimmed the waters in their simple bark canoes with fires lit on clay pads for warmth and cooking. The officers were fascinated; they wondered how on earth the women could manage these 'contemptible skiffs', fishing tackle, onboard fire, small children and babies at the breast, in surf that would terrify their toughest sailors. [10]

[media]The women sang together as they fished and kept time with their paddles as they rowed. They were seen fishing all day, in all weathers, and at night too. Eora women dominated the waters of the harbours, coves and bays, and the coastlines in between. The men mostly only used canoes when they wanted to get from one cove to another. [11]

[media]Eora children grew up on the water from their youngest days, and the swell of the waves and rocking nowie must have been just as familiar to them as the solidity of the earth or their mothers' heartbeat. The girls learned to line-fish as they grew – learning the fishing places and songs, how to burley with chewed cockle, how to lure and snag a fish, how to hone their burra from the cheek of a turban shell.

Eora women's control of the food supply would have been essential to their status and self-esteem, as well as their power in society. So, what may have triggered Barangaroo's anger on first meeting the whites was fish. This meeting, on the north shore at Kirribilli in November 1790, coincided with a massive catch of 4,000 Australian salmon, hauled up in two nets. Forty fish of five pounds (0.5 kilos) each were sent as a present over to Bennelong's group. [12]

Two hundred pounds (91 kilos) of fish may well have been far more than the small group could eat – an extravagant, wasteful gift, given from men to men. As an Eora fisherwoman, winning fish one-by-one through skill and patience, Barangaroo may have felt insulted.

There were ominous implications too: future alliances with these food-bearing whites meant that women would lose their control over the food supply. Barangaroo must have observed the way the whites dealt with Eora men, not women. Living with them, relying on their food, plainly meant dependence on men, white and black. [13]

Yet Bennelong's group did come in to Sydney at the end of 1790. Governor Phillip and the officers were relieved and delighted – though they remained wary and a bit scared of Barangaroo. [14]

Barangaroo had a baby girl in 1791. Bennelong pressured her to give birth at government house – the child would then belong to this new country, Sydney. But Barangaroo refused. She gave birth alone, somewhere in the bush on the edge of the town. David Collins came quietly to see her afterwards and was astonished to see her 'walking about alone, picking up sticks to mend her fire', the tiny reddish infant lying on soft bark on the ground.

But she did not live long after the birth. The officers were silent on why she died. She was cremated, with her fishing gear beside her, in a small ceremony. Bennelong buried her ashes carefully in the garden of Government House. [15]

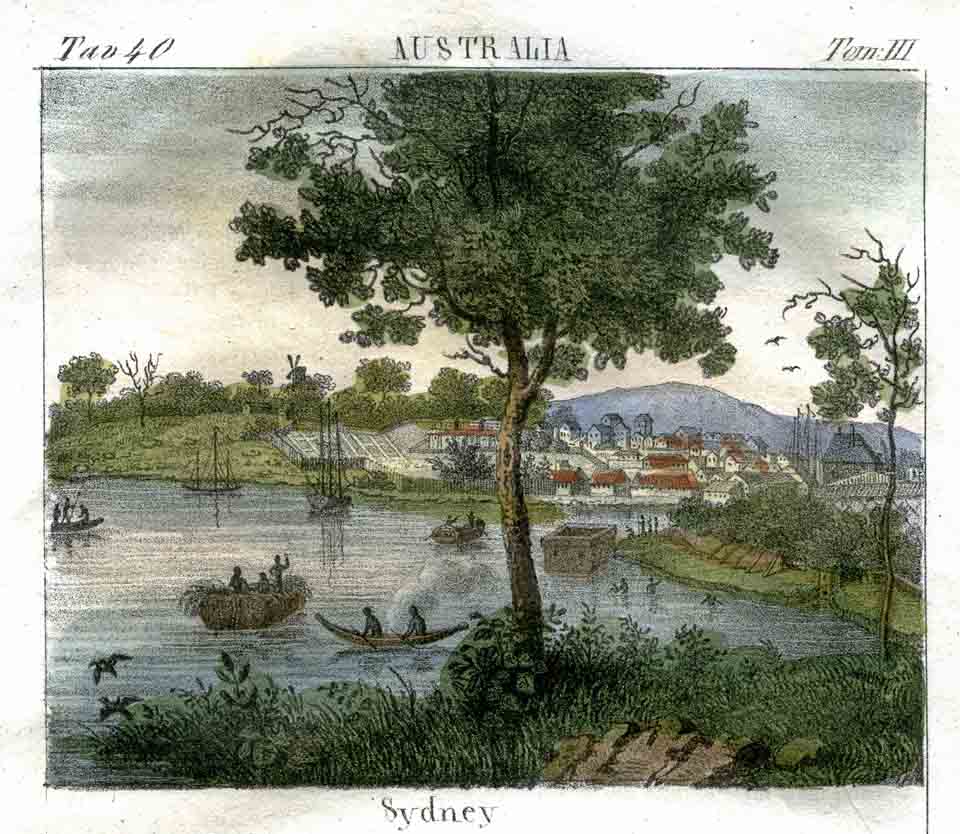

[media]Aboriginal women continued fishing the waters of Sydney Harbour at least until the late 1820s. Forty years after the First Fleet arrived, you could still see their canoes skimming the waves, little plumes of smoke rising from the onboard fires. [16]

We celebrate our harbours and coastlines in poetry, prose and art, in sculptures by the sea. But where in Sydney Harbour, our paradise of waters, are the great Eora fisherwomen remembered?

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigation the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010

Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010

Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, facsimile edition, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 558; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 22–28

[2] William Bradley, 'First interview with the Native Women at Port Jackson New South Wales', drawings from his journal, A Voyage to New South Wales, Dec 1786–May 1792; compiled 1802, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, A3461011, Safe 1/14

[3] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010, pp 53, 402–03

[4] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010, pp 377–8; Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, pp 183–4; John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea, 1787–1792, With Further Accounts by Governor Arthur Phillip, Lieutenant PG King and Lieutenant HL Ball, John Bach (ed), Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1968, pp 310–12

[5] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp 136, 189, 219–29

[6] Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, pp 188, 190, 291; John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea, 1787–1792, With Further Accounts by Governor Arthur Phillip, Lieutenant PG King and Lieutenant HL Ball, John Bach (ed), Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1968, pp 313, 319, 323

[7] Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp 228–29

[8] George Bouchier Worgan, letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12–18 June 1788, includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788–11, July 1788, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/114, p 11; William Bradley, Journal, A Voyage to New South Wales, Dec 1786–May 1792; compiled 1802, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/14, p 133; Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, p 284; Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 886–7; for photographs of the hooks and how they were made, see Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past: Investigating the Archaeological and Historical Records, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 98, 118

[9] George Bouchier Worgan, letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12–18 June 1788, includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788–11, July 1788, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/114, p 11; Daniel Southwell, Diary, 1787–91, in John Thomas Bigge, Appendix to the Report of the Commissioner of Inquiry into the State of the Colony of New South Wales, House of Commons, Parliament of Great Britain, 1822, Bonwick Transcripts, Mitchel Library manuscripts collection, State Library of New South Wales, BT Box 57, pp 244–85; William Dawes, Vocabulary of the Language of N.S. Wales, in the Neighbourhood of Sydney (Native and English), 1790–99, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, Marsden Manuscript Collection, 41645A, 41645b, FM4/3431; Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, pp 189, 221, 283, 286; William Bradley, Journal, A Voyage to New South Wales, December 1786–May 1792; compiled 1802, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/14, p 133; John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1790, published in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society by Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1962, p 159

[10] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, facsimile edition, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, pp 557, 592–93; John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1790, published in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society by Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1962; George Bouchier Worgan, letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12–18 June 1788, includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788–11 July 1788, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/114, pp 9, 23; Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, p 48

[11] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, facsimile edition, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 557; John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, 1790, published in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society by Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1962, p 149; George Bouchier Worgan, letter written to his brother Richard Worgan, 12–18 June 1788, includes journal fragment kept by George on a voyage to New South Wales with the First Fleet on board HMS Sirius, 20 January 1788–11 July 1788, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/114, p 10; Watkin Tench, Sydney's First Four Years, 1793, LF Fitzhardinge (ed), Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979, p 286

[12] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, facsimile edition, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, p 136

[13] Ian Walters, 'Fish Hooks: Evidence for Dual Social Systems in Southeastern Australia?', Australian Archaeology, issue 27, Dec 1988, 98–114; Sandra Bowdler, 'Hook, Line and Dilly Bag: An Interpretation of an Australian Coastal Shell Midden,' Mankind, vol 10, no 4, December 1976, pp 248–57; Val Attenbrow, 'Aboriginal Fishing in Port Jackson and the Introduction of Shell Fish-hooks to Coastal New South Wales, Australia,' in The Natural History of Sydney, Daniel Lunney, Pat Hutchings and Dieter Hochuli (eds), Royal Zoological Society of NSW, Sydney, 2010, pp 16–34

[14] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 2010, pp 386–7; Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove, 1788–1792, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 2001, ch 9

[15] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of Events at Sydney and at Sea, 1787–1792, With Further Accounts by Governor Arthur Phillip, Lieutenant PG King and Lieutenant HL Ball, John Bach (ed), Angus and Robertson in association with the Royal Australian Historical Society, Sydney, 1968, p 360; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol 1, 1798, facsimile edition, Libraries Board of South Australia, Adelaide, 1971, pp 561–62; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers, Text Publishing, Melbourne, 2003, pp 226–27

[16] Jane Maria Cox, ‘Reminiscences, 1813–1880’, in Cox Family Papers, Mitchell manuscripts collection, State Library of New South Wales, A1603; Joseph Holt, A Rum Story: The Adventures of Joseph Holt Thirteen Years in New South Wales 1800–1812, Peter O'Shaughnessy (ed), Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1988, p 69; Hyacinthe de Bougainville, The Governor's Noble Guest: Hyacinthe de Bougainville's Account of Port Jackson, 1825, Marc Serge Riviere (ed and trans), The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Publishing, Melbourne, 1999, pp 70, 173–4; FG Bellingshausen, Journal, March–April 1820 and IM Simonov, Journal, April–May, September–November 1820 in Glynn Barratt (ed), The Russians in Port Jackson 1814–1822, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1981, pp 39, 42, 48

.