The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Barracluff's Ostrich Farm

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Barracluff's Ostrich Farm

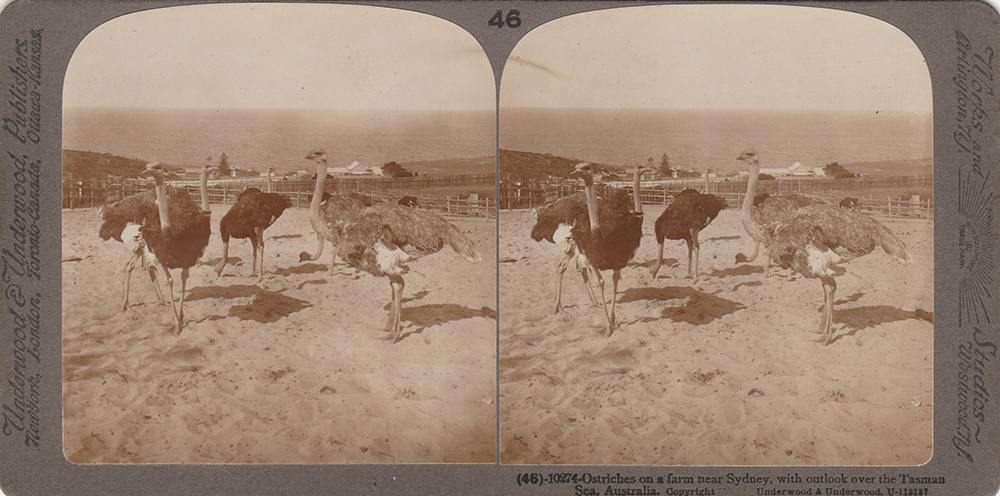

[media]In the late nineteenth century, Diamond Bay on South Head was a relatively remote area with few businesses. Peel's Dairy was situated there and from 1889 to 1918, Diamond Bay also housed Barracluff's ostrich farm.

Joseph Barracluff

Details of Joseph Thomas Barracluff's early life are hazy. His death notice states that he was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire, England in 1861. [1] Yet a florid family history written by Barracluff's granddaughter describes a romantic history of his birth in Southern Russia. [2]

Whatever the truth, it is agreed that Barracluff arrived in Sydney from England in 1884. At the age of 23 he began to sell feathers in a shop in Elizabeth Street, opposite the old Devonshire Street Cemetery (now Central Railway Station). [3]

In 1889 the enterprising Joseph and his wife Jane established an ostrich farm of eleven acres (4.45 hectares) at South Head. The property bordered Old South Head Road, Oceanview Avenue, Military Road and Kobada Road.

As the business grew, so too did the public profile of Joseph Barracluff. He became active in local life and he was an alderman of Waverley for 10 years. During 1914 and 1915 he was mayor.

Ostrich farming

[media]Commercial farming of ostriches had begun in South Africa in 1867 and was highly successful. [4] In 1873 ostriches were imported to Victoria and in 1881 others were brought to Gawler in South Australia. While Barracluff's farm is sometimes described as the first ostrich farm in Australia, that claim must go to the Officer Brothers station in Murray Downs, Victoria. [5] However Barracluff's does appear to be the first ostrich farm in New South Wales [6] and by 1902 the farm had a stock of 100 ostriches. The original ostriches came from Morocco and Egypt, each strain being pure. They were then crossed on the farm. [7]

The birds consumed a ton of food a day and Barracluff fed them with refuse from the railway depot at Darling Harbour as well as markets and large hotels. In exchange for the removal of the waste, Barracluff was permitted to have the leftovers for free. [8]

Farm life

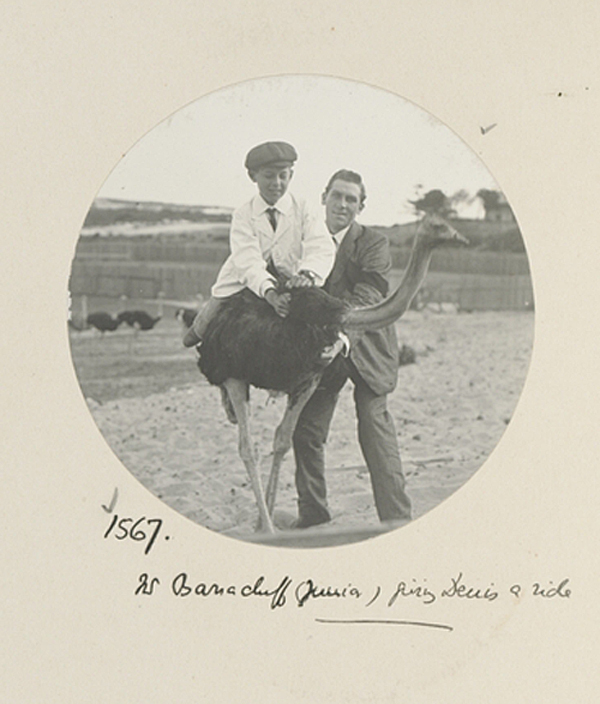

[media]Life could be exciting on the farm. In 1906 an 'Ostrich Chase at South Head' was reported when a male ostrich escaped from the farm. It knocked down a fence and bolted 'with men and boys and dogs in active pursuit'. Three and a half hours later it crossed the Royal Sydney Golf Course before collapsing alongside the tram line. It was eventually conveyed back to the farm a little bruised and battered but was assessed as likely to recover well. [9]

As access to South Head became increasingly easy, over the years the farm became a well-known tourist destination. In the 1890s a tramway terminus was situated at Rose Bay. By 1900 the tram service had been extended to Dover Road before being pushed out to Watsons Bay by 1909. [10] One travel writer of the time commented:

The farm is easily got to by train and bus, and no visitor to Sydney should fail to look up Mr Barracluff who is hospitality itself. [11]

Visiting the farm soon became a popular excursion and patrons could select feathers to be cut directly from the flock.

A royal visit

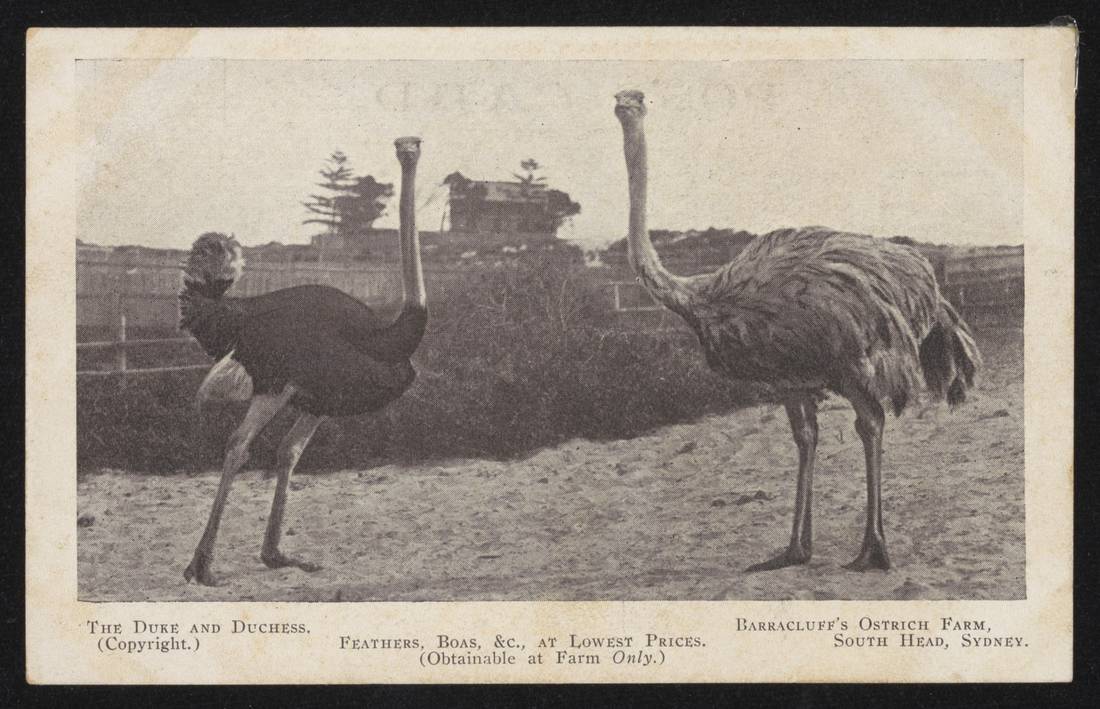

[media]The farm did well and developed a high profile among business circles. This culminated in 1901 with a visit by the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) and her Royal Highness, the Duchess of Cornwall and York (later Queen Mary). This royal tour was one of the most lavish undertaken by the monarchy at that time; its purpose was to open the first Federal Parliament in the Exhibition Buildings of Melbourne. During their visit to Australia, the Daily Telegraph described the royal couple in the following way:

The Duke is extremely pleasant faced and good natured but is apparently not a man of many words….The Duchess has simply captivated everybody. She is one of those women whose photographs don't do them justice. [12]

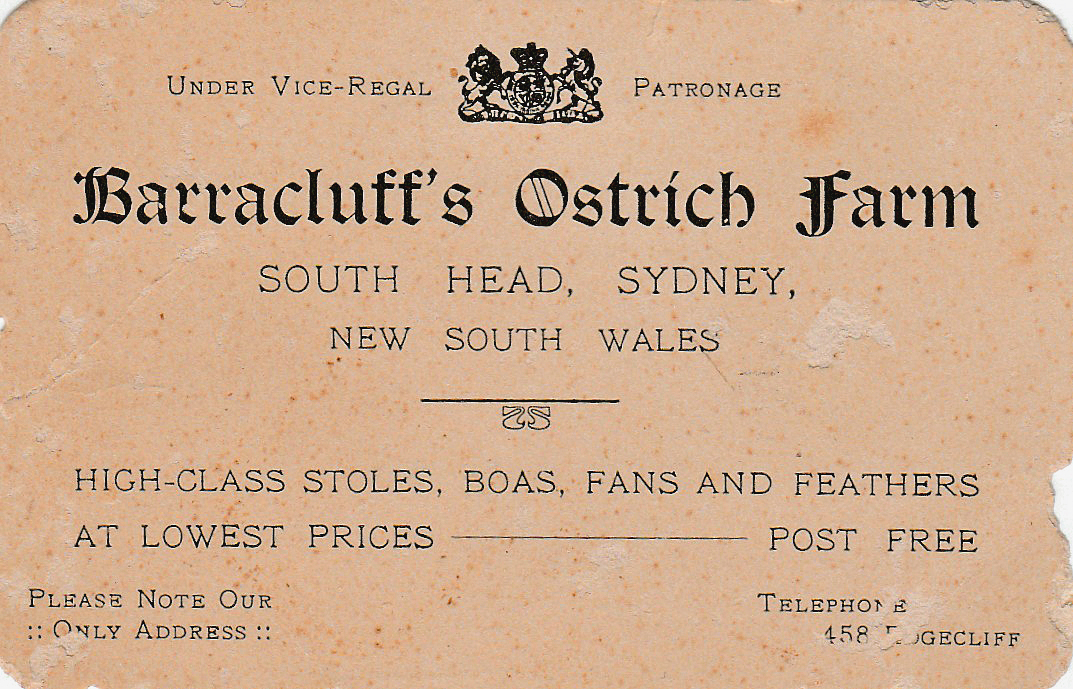

Prominent women of Sydney were pleased to present the duchess with a gold frame and a fan embellished with tortoiseshell and Barracluff's feathers. [13] After the visit the farm was permitted to use the words 'Under Royal Patronage'. In honour of the visit, two birds were renamed 'Duke' and 'Duchess'.

'Fine feathers for fine ladies'

[media]The plumes of ostriches have been used for decorative purposes since ancient Egypt. [14] The farm was commercially successful catering to the high demand for feathers for ladies' hats, boas and fans:

The plume which waves on the head of a strutting beauty has undergone several processes and has been carefully manipulated to fit it for its proud position. It has been dried, then washed in soapy water, in which it has lain in soak for a week. It has then been dried and sorted from its fellows and graded, and finally 'dressed'. [15]

A small number of female staff were engaged to work at the farm under Jane Barracluff to create the products. Ostrich eggs, because of their size and beauty, were prized as ornaments and were finely carved.

Decline

[media]By 1914 with the outbreak of World War I, the demand for ostrich feathers fell almost overnight. [16] Such decoration was viewed as frivolous and unnecessary as changes in ladies fashion took place. There also developed a social stigma associated with wearing feathers and groups of bird protection organisations began to be established.

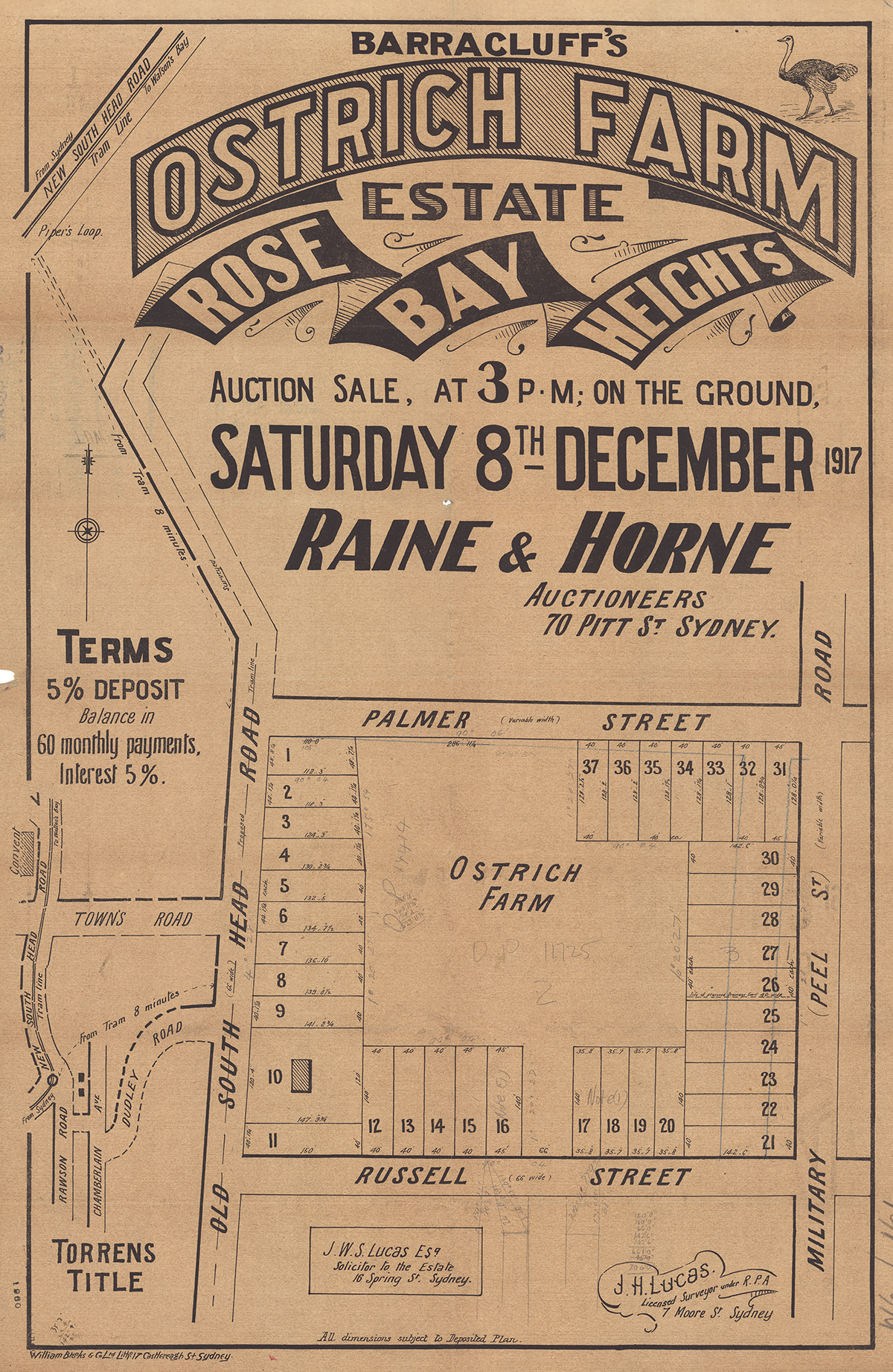

[media]Joseph Barracluff died suddenly at his ostrich farm in 1918 aged 57 years. [17] Soon after his death, the farm folded. Although a partial subdivision of the land commenced in 1917, it was not until 1925 that the farm was completely subdivided. Today, a street and park bear his name.

Further reading

Waverley Library Local History source material. Barracluff's Ostrich Farm, 2008.

Notes

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 1918, 8

[2] Olive Kelly, The Years Between (NSW: Vineyard, 1996)

[3] The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 1918, 8

[4] In 1865 in South Africa, there were 80 tame birds noted. By 1875 numbers had increased to 32,247. MY Hastings, 'A history of ostrich farming – its potential in Australian agriculture,' in Recent Advances in Animal Nutrition in Australia, edited by DJ Farrell, (Armidale: University of New England, 1991), 292–297

[5] The Brisbane Courier, 15 June 1881, 6

[6] The Evening News, 13 March 1902, 2

[7] EJ Banfield, The Gentle Art of Beachcombing: A Collection of Writings, edited by Michael Noonan (University of Queensland Press, 1989), 109

[8] EJ Banfield, The Gentle Art of Beachcombing: A Collection of Writings, edited by Michael Noonan (University of Queensland Press, 1989), 112

[9] The Goulbourn Herald, 2 April 1906, 2

[10] The Sydney Morning Herald, 23 September 1901, 3

[11] The Carcoar Chronicle, 30 March 1900, 6

[12] The Daily Telegraph, 9 May 1901, 5

[13] The Sydney Morning Herald, 7 June 1901, 6

[14] Kenneth V Mathews, 'Ostrich farming in New South Wales', Illawarra Historical Society Bulletin, May 1981, 20–21

[15] EJ Banfield, The Gentle Art of Beachcombing: A Collection of Writings, edited by Michael Noonan (University of Queensland Press, 1989), 112

[16] W Beinart, The Rise of Conservation in South Africa: Settlers, Livestock and the Environment 1770–1950, (Oxford University Press, 2003) 15

[17] The Sydney Morning Herald, 25 November 1918, 8

.