The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

First State funeral

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

First State funeral

The first 'State funeral' in colonial New South Wales was accorded to William Charles Wentworth. He died in England on 20 March 1872 and at his own behest, his remains were shipped back to Australia for burials, a fitting final gesture by the Australian 'patriot'.

The funeral and commemoration of William Charles Wentworth clearly demonstrates the historical associations between commemoration, public memory and national identity. Born in 1790, William Charles Wentworth was 'one of the firstborn of the first generation of natives'. [1] He had a distinguished public career, fighting for representative government in the colony and subsequently becaming a member of parliament in the legislative assembly. It was in this capacity, 'as the foremost champion of freedom in the day, a true leader of the people, [that] he won his chief glory'. [2] According to the Sydney Morning Herald, 'his eloquence was vehement and his invective terrible'. [3] The patriotic Empire reminded readers of Wentworth's contributions in 'early manhood' to the 'exploration of the interior' and, through his studies at Cambridge University, for proving to the British that the colony was producing worthy young men. Wentworth was later instrumental in founding the University of Sydney, seen as an important step in the development of the colony of New South Wales. [4]

[media]The colonial government unanimously voted for a State funeral and appointed three commissioners to make all necessary arrangements for this important public display of gratitude and respect. This was a momentous occasion for the colony. It not only paid tribute to a prominent 'native' Australian through various eulogies, ceremonies and public displays, it also helped to create and present an image of the colony as virtuous and civilized, and a fine young nation. The significance of the first public funeral was not lost on the commissioners, who published a book detailing the origin and progress of all the arrangements. [5] The funeral was covered extensively in the colonial press, allowing some insight into how the ceremony was viewed and how the general public responded to this significant event taking place in Sydney.

Burial of a 'patriot'

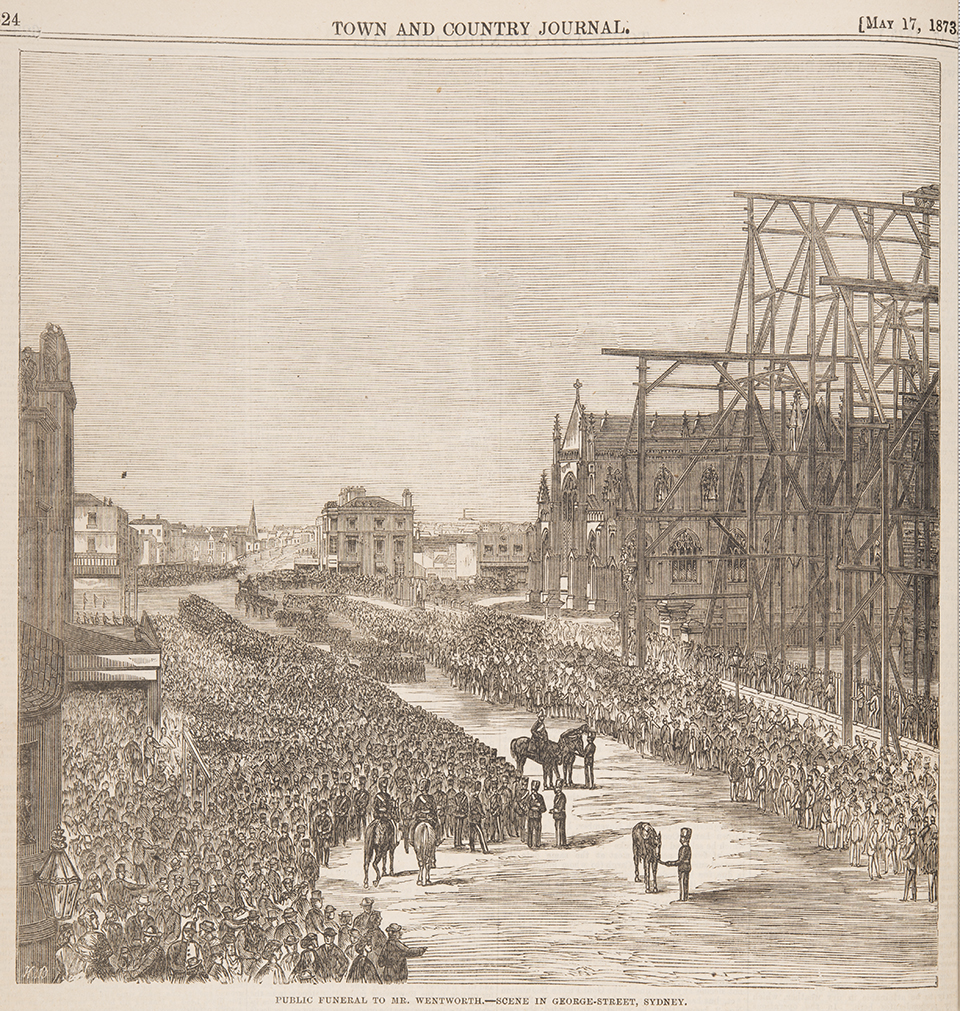

[media]The funeral took place on Tuesday 6 May, 1873 and the day was declared a public holiday by the governor. The memorial service was held in St Andrew's Cathedral where the interior was hung with festoons of black cloth. The corpse was housed in a handsome coffin of polished cedar with silver handles and a shield and covered in wreaths of funeral cypress including two over the lid made from plants indigenous to the Vaucluse area. Following the church service, the funeral cortege paced slowly along the streets to the vault on the Wentworth family estate at Vaucluse. In their detailed descriptions of the 'pageant', contemporary newspapers captured the excitement generated by the unprecedented large-scale display of pomp and ceremony. The order of the funeral cortege and its route were published in local newspapers to encourage public participation and viewing. [6]

The streets were 'alive with excitement' as between 50,000 and 70,000 Sydneysiders flocked to various vantage points to view the funeral procession. By 10am, one hour before the start of the memorial service, 'thousands of well-dressed citizens were making to the various points of the city to view the funeral cortege', and soon 'every possible point of vantage was taken possession of'. 'The footpaths were literally blocked with people'. [7] Heads popped out of every house along the procession route, legs dangled over every shop awing and parapet. Boys perched in trees, atop of gateposts and drinking fountains. [8]

The 'noisy hum of conversation was immediately stilled upon the approach of the procession' [9]; the procession was headed by the volunteer band and behind them marched various institutions and societies, led by the mounted police. The hearse was drawn by four plumed horses, and the glass sides of the carriage allowed spectators a view of the coffin. Behind the hearse came a clatter of carriages: the family and relatives, the governor, the bishop and ministers, the parliament, the judges and the bar, officials from Sydney University, the city alderman, the suburban aldermen, heads of government departments, the clergy of various denominations, officials and other gentlemen. [10] The funeral cortege was extremely long and took several hours to pass. According to the Empire newspaper, when the first portion had reached the toll-bar at Rushcutters Bay, the last of the carriages had not left George Street'. [11]

The funeral was praised for being 'deeply impressive' and a fine 'spectacle'. [12] The procession finally reached Vaucluse at around 2 o'clock, by which time 'the patience of the beholders was well-nigh exhausted'. [13] There was some criticism of laughter, talking and pipe-smoking amongst the volunteer force during the procession, such behaviour being condemned as contrary to 'those feelings of quiet solemnity which such an occasion should inspire'. [14] However, overall there was general agreement that despite the large crowd and the lengthy procession, the behaviour of the spectators was decorous and orderly. [15] The newspapers unanimously agreed that the State funeral was a fitting tribute for Wentworth, 'the great Australian patriot', and that it was an important and defining moment in the development of the nation's collective memory and identity.

The Funeral Reform Movement

Given the success of the first State funeral, it is perhaps surprising, and certainly ironic, to learn that 18 months later the first manoeuvres to implement funeral reform were underway. The Funeral Reform Association of NSW was founded in Sydney on 27 October 1874, chaired by Thomas S Mort. The association aimed to do 'away with the absurd pomp and ceremony connected with the funerals of ordinary folk' and 'to bring about a system of simple and decent burial of the dead'. [16]

Members of the association agreed to adhere to and promote simple funeral customs. Their list of regulations provides a foil to the common accoutrements of a funeral in the 1870s:

- That the coffin be plain, and, so far as may be, free from adornment.

- That no pall be used; that neither scarfs nor hatbands be worn nor gloves be provided; neither shall there be mutes nor plume-bearers.

- That the hears or carriage in which the body is conveyed by plain and devoid of decoration; that the horses wear neither plumes nor trappings, and that in lieu of mourning coaches ordinary vehicles be employed.

- That the hearse and other vehicles be driven at a somewhat quicker pace than the ordinary walk.

- That there be no funeral procession; that mourners other than relatives or special friends meet at the Mortuary or burial ground only; and that no invitation to a funeral appear in the public prints.

- That mourning, after the present costly, inconvenient, and unhealthy fashion be avoided, and that the ordinary attire, both of men and women, with the addition of a black crape or cloth band or bands on the hat or left arm, be considered respectful and sufficient mourning. Sydney Morning Herald, 5 December 1874, p 1

The Funeral Reform Association aroused much debate amongst the upper class in Sydney. It gained supporters amongst religious ministers, parliamentarians, medical practitioners and society leaders. At one stage the Funeral Reform Association had 500 members. However, the association foundered after the death of Mort in 1878. The movement regained momentum in 1890 when it became associated with both cremation and sanitary reform. Together these three movements – the modern cremation movement, funerary reform and medical and sanitary improvement – gradually changed attitudes towards death in the twentieth century.

References

Lisa Murray, 'Cemeteries in Nineteenth-Century New South Wales: landscapes of memory and identity', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 2001

Notes

[1] Editorial, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 4

[2] Editorial, Empire, 6 May 1873, p 2

[3] Editorial, Sydney Morning Herald, 5 May 1873, p 4

[4] Editorial, Empire, 6 May 1873, p 2

[5] Public Funeral of the Late William Charles Wentworth. Tuesday, 6th May, 1873. Government Printer, Sydney, 1873

[6] Public notification of procession order and other arrangements, Empire, 5 May 1873, p 1

[7] Empire, 7 May 1873, pp 2 –3; Illustrated Sydney News, 13 May 1873, p 3

[8] Illustrated Sydney News, 13 June 1873, p 3

[9] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 5

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 5

[11] Empire, 7 May 1873, pp 2 –3

[12] Editorial, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 4

[13] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 5

[14] Illustrated Sydney News, 13 May 1873, p 3

[15] Editorial, Sydney Morning Herald, 7 May 1873, p 4; Illustrated Sydney News, 13 May 1873, p 3

[16] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1874, p 3

.