The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Liverpool Internment Camp during World War II

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Liverpool Internment Camp during World War II

[media]At the beginning of World War II, the army needed to set up a camp for Germans who were being interned. The camp that had been used at Holsworthy during World War I was not retained after the internees left. The buildings were mainly temporary, put up by amateur builders, mostly by the internees themselves, from local building materials. In December 1919, The Argus ran an advertisement for '…an extensive sale of building material removed from the Holsworthy [1] Concentration camp', being material from 'theatre, picture show, canteen, platoon etc' [2], which seems to indicate that the demolition of the site began even before the last prisoners were released.

The site chosen was the Anzac Rifle Range, described as being at Moorebank, near Liverpool. It needed to be set up in a hurry, so cottages and huts belonging to the rifle associations who used the range were commandeered for this purpose. A barbed wire fence was put up around the buildings on one side of the road to house the internees. The military guards and administration staff were housed on the other side of the road. [3] In his article for the Sydney Morning Herald in November 1946, JW Morris mentions that the internees in World War I built the huts for the rifle range and that these were subsequently remodeled to suit the needs of each compound. [4] Morris notes that the camp provided '…excellent living and recreational quarters for the inmates during their imprisonment'. [5]

[media]The camp at Moorebank commenced on 15 October 1939 under the direct control of the Australian Army Base at Victoria Barracks, Sydney. It was officially known as 'The Internment Camp, Liverpool'. In 1940 the camp was considered to be too small and was closed when larger camps were built at Orange and Hay. However, after eight months the camp was re-opened, as there was a need for a camp near Sydney for internees in transit to other states and as a holding camp for 'special internees.'

Special internees

[media]One group of these 'special' internees comprised members of the Australia First Movement, which was an organisation seen as anti-English, anti-Semitic, anti-United States and pro-Fascist, pro-Nazi and pro-Japanese. [6] This meant that its members were considered a security risk. In March 1942, under the authority of section 13 of the National Security Act, a bus collected 13 men from police stations around metropolitan Sydney and took them to the Liverpool internment camp. The National Security Act 'empowered any constable or Commonwealth officer or anyone authorised by the Minister for Defence to arrest without warrant anyone found committing an offence against the Act. [7]' However, another clause 'provided for the release of the suspected person within ten days of arrest if no charge was laid.'

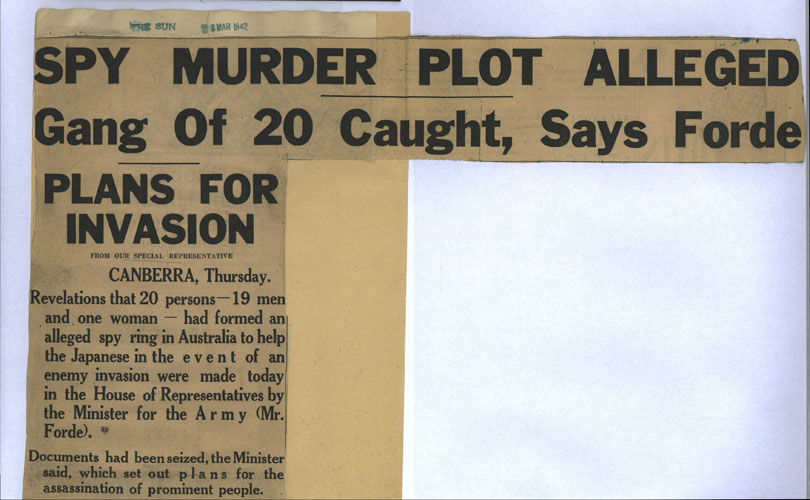

The men were detained and then on 25 March, five days after the legal limit for their detention, they became internees. Sydney's afternoon papers on 27 March gave the internees and their guards some idea of what was being held against them: 'Spy Murder Plot Alleged' was the banner headline in The Sun over a report which referred prominently to 'Treason at its worst' and 'Gang of 20 caught. [8]' Some were released early while others were later sent to Loveday in South Australia and not released till later in the year.

However the vast majority of internees who passed through the camp were from overseas. The nationalities of those listed in an official army list were: German, Austrian, Italian, Finnish, Portuguese, Spanish, Norwegian, Vichy French, Greek, Danish, Czechoslovakian, Hungarian, Romanian, Russian, Japanese, Thai, Javanese, Chinese, Solomon Islanders and Indonesian. The internees included two Rhodes scholars, doctors of medicine, a retired bank manager, engineers, business executives, master mariners, soldiers and sailors. [9] The 'most troublesome' were said to be the Germans and Japanese. Morris mentions that while generally behaving in a docile manner, the Japanese internees objected to their status as prisoners and one man asked an officer to shoot him and put him out of his misery. This was part of the Japanese culture that believed death was honourable, but capture brought dishonour.

The Javanese and Chinese internees were mainly seamen who refused to go back to sea with their ships because of the risks involved. One group of Chinese detainees who had refused to sail with their ship had been put to work in the garden. When they finally agreed to rejoin their ship they asked to stay for an extra two weeks as they claimed '…they were having the best holiday they had enjoyed for some time.' [10]

Guards

The guards at the camp were enlisted personnel and the first guard duty was the responsibility of the 1st Garrison Guard, then later the 15th Garrison Battalion, and by 1944, the 21st Garrison Company, [11] with the garrison strength varying from 80 to 120 personnel. Morris recalls that the officers were '…seasoned soldiers of World War I, who understood human nature thoroughly.' [12] As the camp was used as a staging camp, there were sometimes women sent there, so there were also two wardresses to care for and escort female detainees who were kept in a separate compound within the camp.

Labour and leisure

[media]Under international law, work within the camp was compulsory for prisoners of war but not for civilian internees. They did, of course, take part in the everyday work in the camp such as cooking, cleaning up and collecting firewood. Other work in which the internees could take part included cabinet-making, carpentry, blacksmithing, tent-making, wood-cutting and gardening. The latter was a popular occupation and the five-acre (approximately 2 hectare) garden produced many tons of fresh vegetables which not only served the camp's needs but also those of the nearby Holsworthy Barracks. It was also possible to engage in a number of hobbies, with weaving being particularly popular.

Internees could receive visitors once a week, usually on Sunday afternoons in a special hut that had wide tables down the centre with internees on one side and visitors on the other, separated by a wire-netting grid to stop physical contact.

Internees provided most of their own entertainment but the YMCA also provided some. Groups often sang folk songs during the evening. On one occasion 29 Nazi seamen were brought in from the German raider Kormoran. They sang a 'particularly beautiful song' and the next morning the adjutant asked the interpreter what it was about. 'He was politely informed that it was a hymn of hate on the subject of the sinking of HMAS Sydney!' [13]

Generally life in the camp was as good as it could be, considering the internees did not have their freedom and the problem of monotony that affected some internees. One article commented that '…some said their period of internment was the best rest they ever had in their lives,' [14]

Escape

There is only one mention of escape from the camp and that was in 1940. This was presumably Alfred Fritz Yackels (alias Joseph Alfred Schmidt) who was described as having a criminal record that went back several years so he had been interned as an enemy alien living in Australia. It was believed that Yackels concealed himself in a sanitary van that had called at the camp on 10 February. [15] He was captured in Balmain on 23 February. A woman named Marie Smith was also arrested with him. [16] One paper reported that she had attacked the detectives who arrested Yackels. [17]

By late November 1946 the camp closed and, according to Morris, returned to the Metropolitan and State Rifle Associations '… in far better condition than when they were taken over.' [18]

References

JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946

Notes

[1] Holsworthy was often spelt this way in the early twentieth century

[2] Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers' Advocate, 13 December 1919, p 13

[3] Special correspondent, 'Behind Barbed Wire at Liverpool', Sydney Morning Herald, 23 February 1954, p 8

[4] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946, p 8

[5] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946, p 8

[6] 'Australia First Movement: Opening of Inquiry', Kalgoorlie Miner, 20 June 1944, p 2

[7] National Security Act became law on 9 September 1939

[8] In Bruce Muirden, The Puzzled Patriots: The Story of the Australia First Movement, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria, 1968

[9] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946

[10] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946

[11] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946, p 8

[12] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946

[13] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946

[14] Special correspondent, 'Behind Barbed Wire at Liverpool', Sydney Morning Herald, 23 February 1954,

[15] 'Internee at Large', Sydney Morning Herald, 12 February 1940, p 13

[16] 'Internment Camp Escapee', Sydney Morning Herald, 4 March 1940, p 12

[17] 'It happened on…', Nambour Chronicle and North Coast Advertiser, 1 March 1940, p 4

[18] JW Morris, 'Rifle clubs return to Anzac Rifle Range', Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 23 November, 1946, p 8

.