The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Manly

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Manly

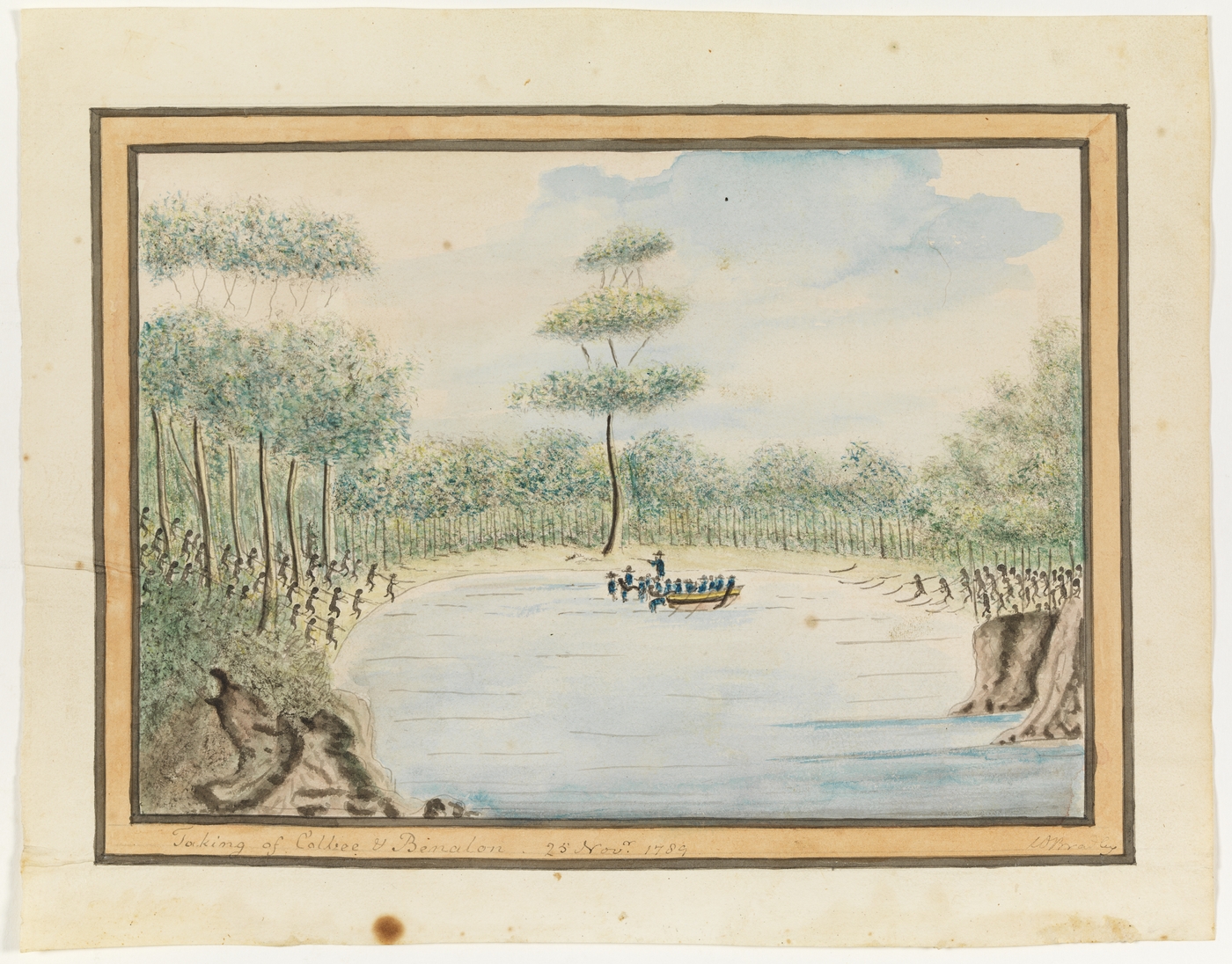

Manly was originally inhabited by the Cannalgal and Kayimai people.

[media]The first official dispatch in 1788 from Arthur Phillip, governor of the newly founded imperial outpost in New South Wales, noted the 'confidence and manly behaviour' of the Aboriginal people encountered on the northern side of the entrance to Sydney Harbour. Thus Manly derived its name. In 1868, however, their decimation was symbolised by the theatrical importation, reported in the Sydney Morning Herald on 13 March, of a 'troupe' of Aborigines to demonstrate 'war games' on Manly's ocean beach for the entertainment of European excursionists.

The Brighton of the South Pacific

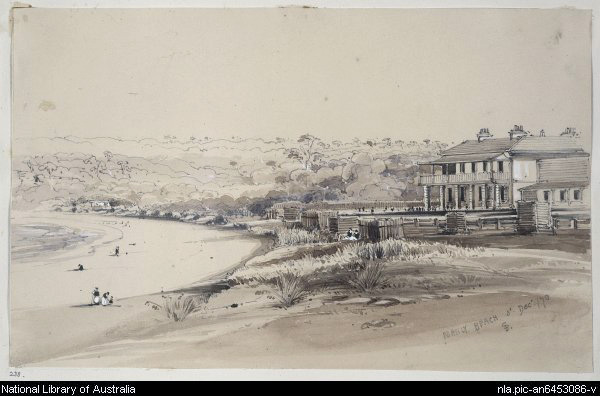

[media]Manly is one of Australia's oldest and most famed public 'watering places' and pleasure grounds. From the mid-1850s – when its handful of residents numbered around 70 – Henry Gilbert Smith became the first of many to market Manly as the Brighton of the South Pacific. On 5 January 1876, a number of Manly citizens gathered in public to discuss the formation of a municipality. As a result of this meeting, 63 signatures – thirteen more than were required under the Municipalities Act of 1867 – were appended to a petition seeking permissive incorporation.

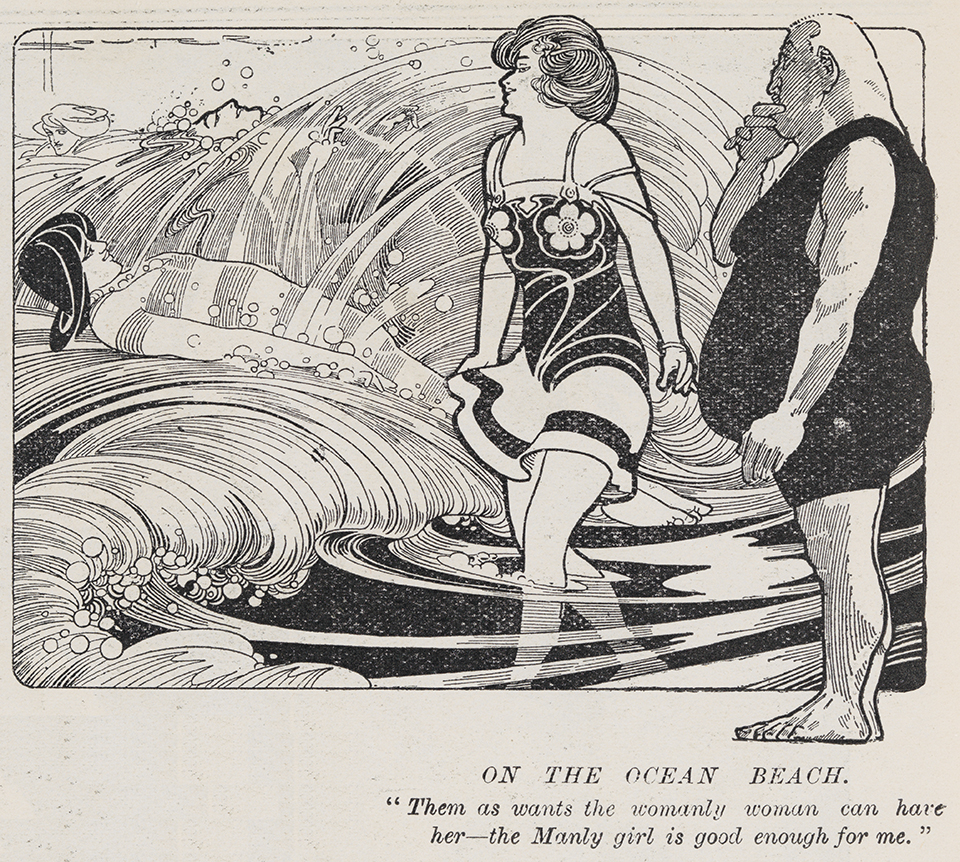

[media]The Municipalities Act also required applicants to delineate an area and give it a name. The petitioners sought a charter for 'Brighton' – shortly to be amended to 'Manly' – between the village of Manly and The Spit. The first chosen name reflected the sought-after Brighton-Eastbourne-Blackpool connection, an axis for the famous and the fashionable which epitomised the healthy seaside culture.

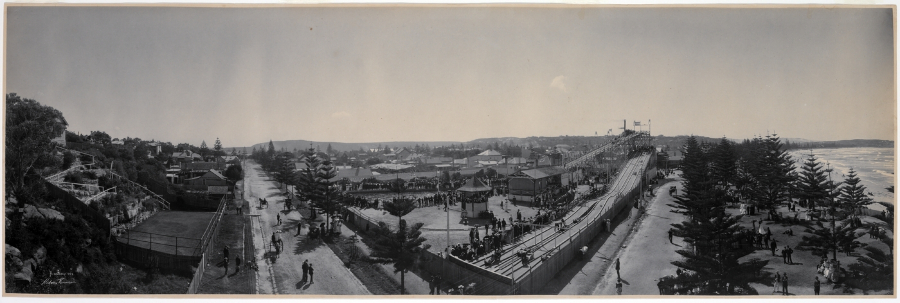

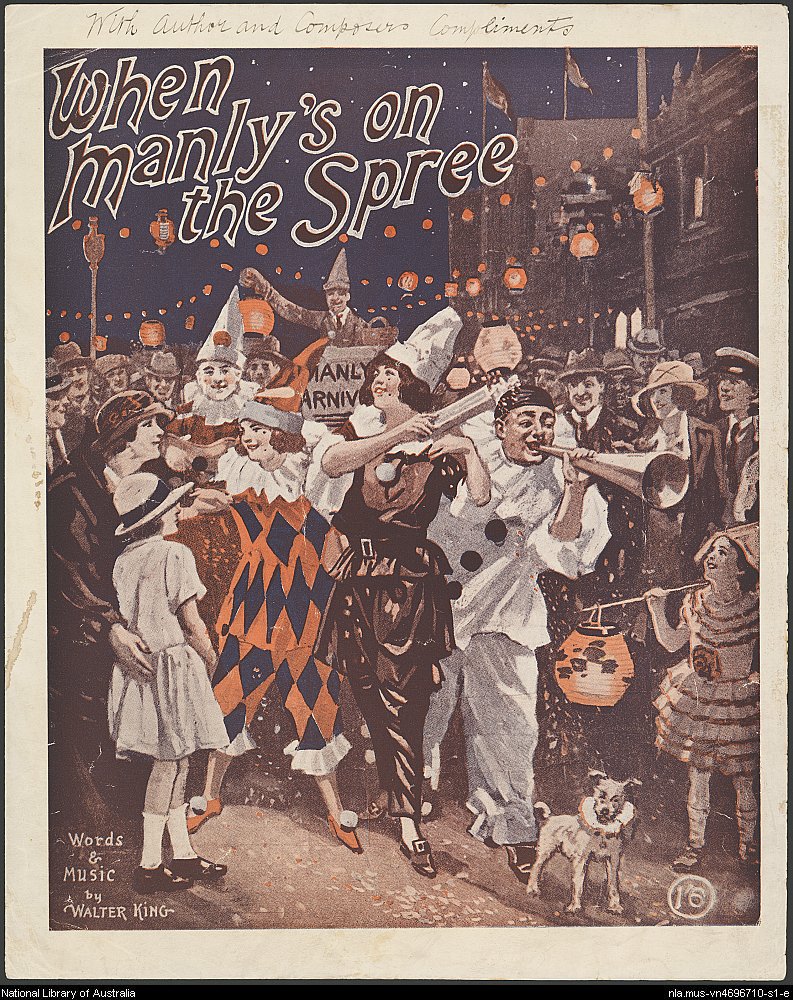

Manly was [media]resolutely promoted by developers, civic worthies, ferry companies, real estate agents and some medical practitioners who saw the place as a sanatorium. The British-style resort was to figure prominently in the rise of beach culture from the second half of the nineteenth century until the 1920s, when the myth of the beach fully emerged. Improved transport to and from the city of Sydney saw the population rise from 500 in 1871 to 1,327 in 1881, 3,236 in 1891 and 5,035 in 1901.

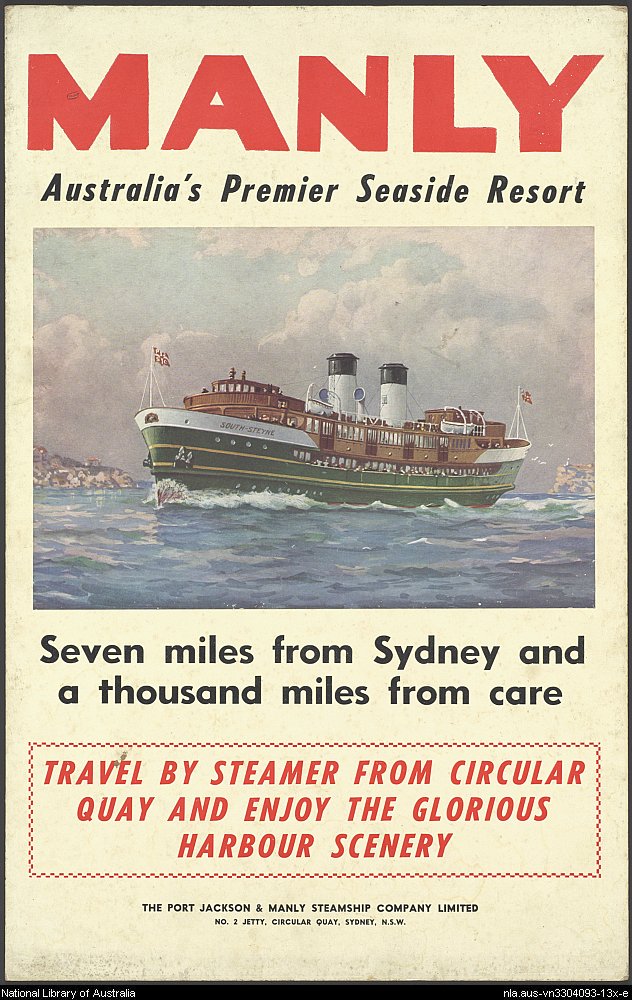

Seven miles from Sydney and a thousand miles from care

As [media]the Manly and Port Jackson Steamship Company's popular slogan trumpeted, the place was 'Seven miles from Sydney and a thousand miles from care'. For most of the nineteenth century, however, Manly, for the majority of people, might as well have been a thousand miles from Sydney. Until bridges and roads connected the municipality directly with the city, Manly remained largely the haunt of the wealthy – including politician and orator WB Dalley, timber merchant WH Rolfe and shipowner William Spier – and their servants and providers. The remnants of Dalley's 'Castle' can be seen today in the form of sandstone walls and carvings on the southern side of Sydney Road opposite Ivanhoe Park.

Later, less eminent residents, like the throngs of tourists, were drawn by the appeal of sun, sand, surf and sea. Such attractions were heightened after World War I following the liberalisation of local bathing by-laws in 1903 and the introduction of surfboard riding in 1915.

The [media]development of flats after the World War I added a further enticement, as it did in other fashionable seaside locales. Offering a chic and casual lifestyle for singles, young couples and retirees – too casual for some conservative social commentators – a huge wave of flat and bungalow development washed across the municipality, burying the Victorian village under a 1920s red- and brown-brick suburb. During that decade, around 400 flats were built in Manly. Of all new flat construction in Sydney municipalities, Manly's was the sixth highest in this period. A similar number were built in the following decade. Many remain.

Manly's geographical [media]isolation engendered the development of an independent, self-contented community. But it was, and continues to be, dependent on tourism. The area's function as a resort has also meant that, from the 1920s on, around half of Manly's population has been semi- or non-permanent. Both tourism and the area's population were stimulated by the construction of the Spit Bridge in 1924 which replaced a punt that had been operating from the nineteenth century. The introduction of government buses from 1932 also facilitated access to Manly.

[media]After World War II, however, aged and deteriorating facilities, combined with changes to the tourist market, led to a significant decline in stopover visitors. This became acute by the early 1960s. The rise of both the car and the backyard swimming pool also undermined harbourside resorts as people flocked to surf beaches or swam at home. A burst from the mid-1970s of civic rejuvenation and successful local protest which reversed the decline of ferry services contributed to a period of urban gentrification which continues in the twenty-first century.

Manly's politics

Despite its easygoing reputation, Manly has historically been a conservative place. It was a safe seat for the Australian Liberal Party until the 1990s, when it was won by an independent and held for four terms, until being reclaimed by the Liberal Party. It has also captured the imagination of creative Australians. Manly has been depicted in paintings and photographs, such as David Moore's 1964 iconic image of a surf lifesaving carnival on Manly Beach, as well as books such as John O'Grady's The y're a Weird Mob (1957) and Roger Millis's autobiographical novel Serpent's Tooth (1984), and films such as Fred Schepisi's The Devil's Playground (1976).

References

Paul Ashton, 'Thematic History', vol 2, Kate Blackmore and associated consultants, Manly Heritage Study, Kate Blackmore, Sydney, 1986

Paul Ashton, 'Inventing Manly', in Max Kelly (ed), Sydney: City of Suburbs, University of New South Wales Press in association with the Sydney History Group, Sydney, 1987, pp 149–171

Pauline Curby, Seven Miles from Sydney: A History of Manly, Manly Council, Manly NSW, 2001

PW Gledhill, Manly and Pittwater: its Beauty and Progress, Manly, Warringah and Pittswater Historical Society and Robert Dey, Son & Co, Sydney, 1948

F Myers, Beautiful Manly: illustrated views of Eastbourne in the marine suburb, Manly and the favorite watering place of New South Wales, Anglo-Australian Investment, Finance & Land Company, Sydney, 1885

Charles Swancott, Manly 1788 to 1968, DS Ford, Sydney, 1968