The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Maroubra

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Maroubra

'Maroubra' [media]is an Aboriginal word for 'like thunder' and the area was so-called for the heavy and sometimes wild surf pounding against the rocky beach. [1] Before white settlement, the area was popular with the local Muru-ora-dial Aboriginal people as a camping ground and a place to fish. Evidence of their presence is recorded in rock carvings on the north headland at Maroubra. A remarkable stone workshop, with many Indigenous tools and implements, was discovered on the south end of Maroubra Beach in the early twentieth century. [2]

[media]For the first one hundred years of white settlement in New South Wales, the area was largely undeveloped. In a map of Sydney from 1892, it does not even feature a mention. [3] Dramatic shipwrecks along the coast in the late nineteenth century drew attention to this little visited area but it wasn't until the early twentieth century that development began in earnest, turning this once isolated beach area into a smart and substantial village. Today Maroubra is the largest suburb in the area governed by Randwick City Council.

Early settlement

[media]Early settlers such as Humphrey McKeon, who bought land here in 1861 and built the first house in the district, thought that the isolated site would be a suitable place for wool washing or scouring, [4] an industry that was a rather unpleasant, malodorous branch of what were then termed the 'noxious trades.' And so wool washing became a local industry around Maroubra in the 1870s. Located at the northern end of the bay, the wool scouring works drew more settlers to the area. [5] Despite this, much of the surrounding area remained isolated and undeveloped until the end of the nineteenth century. [6]

It was a spectacular disaster in the area that finally placed Maroubra on the cultural and social map of Sydney. In May 1898 wild storms hit the east coast of New South Wales. On 6 May the Maitland steamship was wrecked near Broken Bay with a heavy loss of life. The Glasgow built, 1,513 ton iron clipper, the Hereward, was also caught in the storm and driven ashore between two reefs of rock on the northern end of Maroubra beach. Despite the dramatic beaching of the vessel, fortunately there was no loss of life and the twenty-five crew members landed ashore safely. [7]

[media]The wreck of the Hereward remained on the beach for six months before salvage attempts were made. During this time thousands of inquisitive and curious Sydneysiders travelled by bicycle or horse to view the beached wreck. During another violent storm in December 1898 the Hereward broke into two and it wasn't until the middle of the twentieth century that attempts were made to clear the remains from the area. [8] Today the Hereward shipwreck is remembered in the street named after it within the area. [9]

Other impressive shipwrecks on Maroubra Beach involved the New Zealand steamship the Tekapo that ran aground in May 1899 and later, the coastal freighter the Belbowrie that crashed into rocks at Maroubra Point in January 1939 and broke up almost on impact. [10] In 1986 the anchor of the Tekapo was recovered and today hangs in the Maroubra Surf Life Saving Club as an enduring reminder of the enormous might and power of the sea. [11]

Residential development

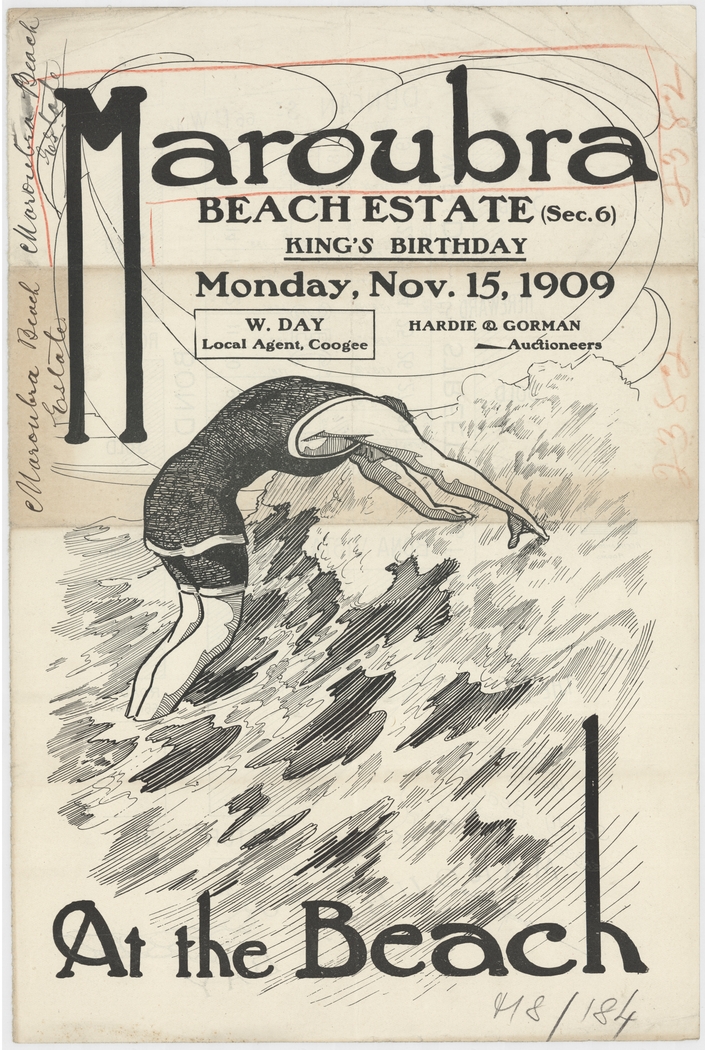

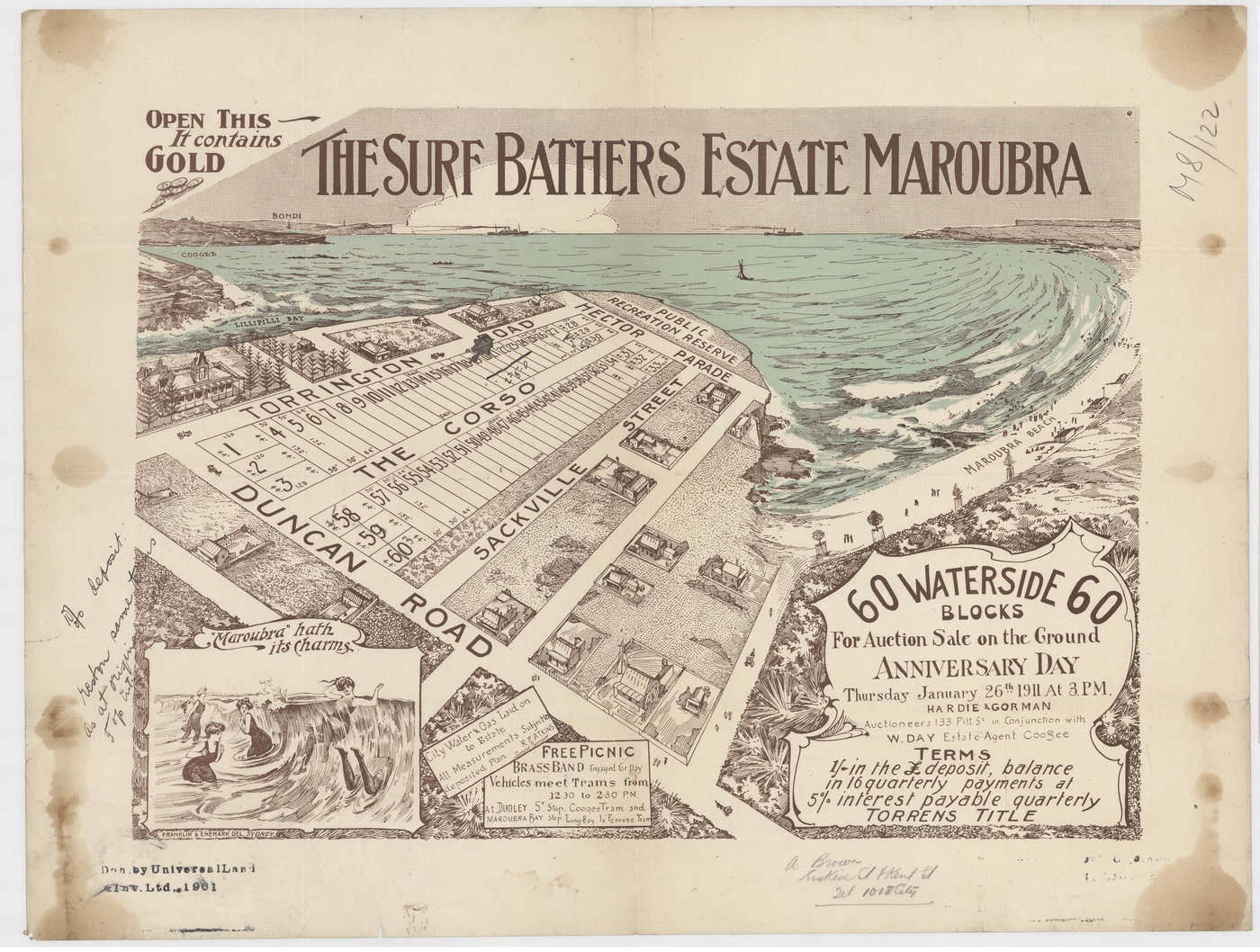

Maroubra's [media]residential development finally commenced in the second decade of the twentieth century. On Australia Day 1911, 60 waterside blocks situated along Torrington Road, the Corso and Sackville streets, were advertised to be auctioned as The Surf Bathers Estate Maroubra. [12] A free picnic and brass band provided suitable Sydney beachside entertainment for the grand occasion. By this date the seaside was no longer a place to just visit on the weekend; indeed the popularity of the idea of actually living near the beach was reflected in rising land values in the area. In September 1911, The Sydney Morning Herald reported that land values had risen from 5 shillings per foot to £5 and £6 per foot within the previous five years, which amounted to a twenty-fold increase. [13]

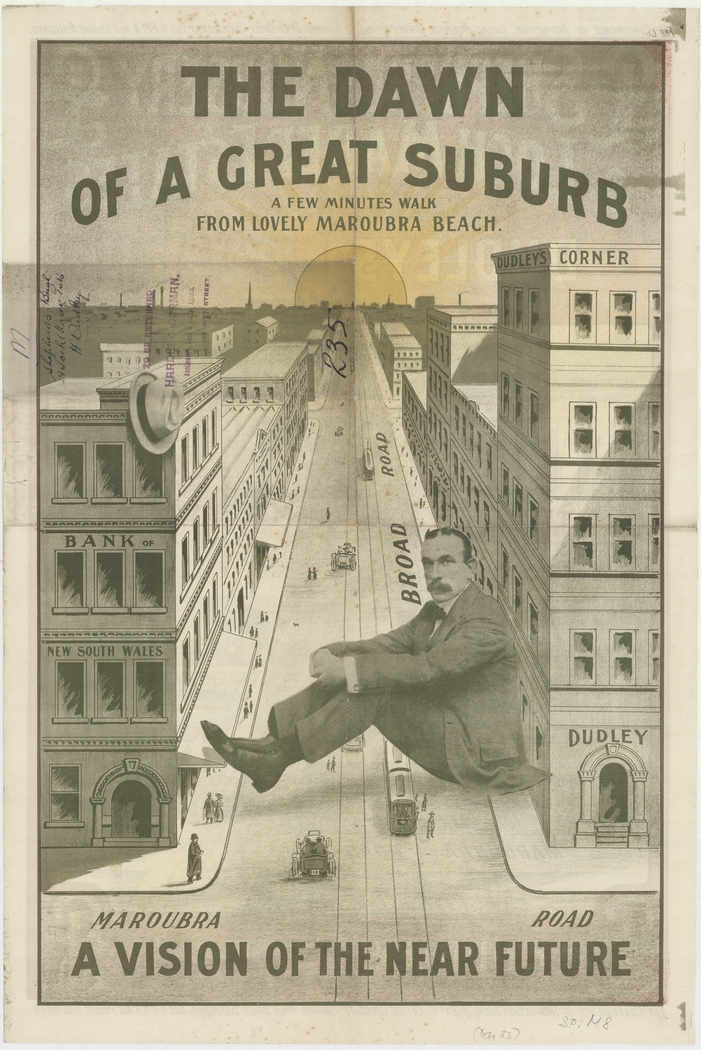

[media]One of the prime movers and shakers in the development of Maroubra was Herbert Dudley, a real estate developer with an entrepreneurial flourish and flair. Dudley actively oversaw the development of Maroubra from an isolated beach area into a smart and substantial village. Indeed, his famous bold slogan was 'Watch Maroubra Grow!' [14] [media]Mindful of the need for community services and facilities to ensure the growth and development of flourishing residential areas, Dudley built the magnificent Dudleys Emporium on the corner of Anzac Parade and Maroubra Road, Maroubra. [15] The Emporium, which opened in 1913, was a popular and substantial landmark; it had a hardware store, a grocery store, a drapery, a chemist, a butchery as well as a cinema where lively regular crowds gathered and also enjoyed the refreshment amenities available. Dudley also built the original Maroubra Junction Public School. [16]

Maroubra Junction[media] soon became a busy hub where a variety of shops and businesses served the local community well. By the 1920s Maroubra Junction was a flourishing and popular spot and the majestic Maroubra Junction Hotel opened its doors there in 1927. Much of this development was encouraged by the modernising forces of the transport revolution; indeed, the construction of a tramline to the beach commenced in 1920 and soon the trams began bringing enthusiastic crowds to the seaside on weekends and holidays. The tram departed from Anzac Parade with the terminus was located at Marine Parade. Buses and cars later become the favoured means of transport and the last tram to Maroubra made its final journey on Saturday 25 February 1961. [17]

Maroubra speedway

[media]In 1925 the Olympia Speedway Maroubra opened. It was built near the corner of Fitzgerald Avenue and Anzac Parade. This was Australia’s first major motor racing venue and it was greeted with great excitement and speculation. Indeed, its opening day attracted adoring crowds of over 67,000 enthusiastic motoring spectators. Here they watched bikes and speed cars zoom laps around the 1.6 kilometre long concrete track. Many of the drivers who participated at the Olympia Speedway went onto become household names; among them, Phil Garlick, Hope Bartlett, Charles East, Fred Barlow and Alan Cooper. Thrilling and innovative as this new sport must have been for Sydneysiders [media]in the 1920s, a series of fatalities involving both drivers and spectators led to its sombre moniker 'the killer track'. Indeed, the dangerousness of the venue, and the sport itself, led to the end of car racing there in 1928. Motorcycle racing continued into the following decade. However, in the middle of the Depression years, with crowd numbers dwindling as austerity measures reduced incomes and spare cash for leisure pursuits, the speedway closed in 1934. [18]

Maroubra Beach

[media]After daylight bathing was legalised in 1902, Maroubra beach became a popular place for swimming and body surfing. Indeed, within a few years of the lifting of the daylight hours swimming ban, Maroubra already had two surf lifesaving clubs, one at each end of the beach. At the northern point, the club was known as the North Maroubra Life Line Club and to the south, the South Maroubra Surf Club. The two would eventually merge to become Maroubra Surf Club. When the Surf Bathing Association of New South Wales was formed in 1907, Maroubra became one of its founding members. [19]

Maroubra Beach became highly significant in other ways during the Depression years of the 1930s. The sand hills and dunes of the beach became the site of numerous makeshift homes and camps for many Sydneysiders suffering the effects of unemployment and eviction from their rented homes in the inner city. [20] At Maroubra many people found sanctuary and a sense of community on the far-flung fringes of the city. Swapping unhealthy overcrowded tenements for the bracing open landscape of sea air and better health, many stayed in these camps until the close of the 1930s. [21] Interestingly, it was also during the 1930s that Maroubra surf club erected a substantial clubhouse and surf sheds, providing much needed employment and further amenities to attract people to visit the area.

[media]During World War II Maroubra Beach was taken over by the army and barbed wire was strung from the north to the south end of the beach. Later the beach was used for target practise when American troops arrived to train in the area. [22] Invasion anxieties pervaded the Australian consciousness during these years. Despite this, at Maroubra and elsewhere, Sydneysiders continued to go to the beach and enjoy the surf even in the midst of war.

Today, surviving photographs of the war years attest to the beach as a place to escape to during these anxious, uncertain years. After the war, The NSW Housing Commission, perhaps mindful of the plight of many living near or on the beach in the depressed 1930s, established itself in the Maroubra area. The housing commission appropriated the site of the long abandoned Maroubra Speedway in 1947 and rezoned it as a residential area. [23] Later, in 1951 the construction of the Coral Sea Housing Estate began and it was finally opened in 1961. [24]

In 2006, Maroubra Beach was honoured by becoming the second only Australian beach to be declared a national surfing reserve, the first being the famous, wild and spectacular Bells Beach in Victoria. Maroubra Beach was formally dedicated on Sunday 19 March 2006. [25] In 2007, this intimate connection was documented in Bra Boys: Blood is Thicker than Wate r. Featuring Russell Crowe as narrator, the film depicted the cultural evolution of the Sydney beach side suburb and the social struggles faced by its youths – the notorious surf gang known as the Bra Boys.

And so, almost one hundred years since the Bathing Association of New South Wales was first established, with Maroubra as one of its founding members, the long and enduring history of beach culture and surfing at Maroubra, and its place in both the local and national consciousness, was firmly cemented.

Further reading

Ford, Caroline. Sydney Beaches A History. Kensington: New South Publishing, UNSW Press, 2014.

Pollen, Frances. The Book of Sydney Suburbs. North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1988.

Scott, Mark and Tony Nolan. Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra. Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014.

Randwick Municipal Council. The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide. Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990.

Notes

[1] Since 1907 the Maroubra Surf Life Saving Club flag and uniform have honoured this connection

[2] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 4

[3] Frances Pollon, The Book of Sydney Suburbs (North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, NSW, 1988), 64

[4] Scouring involved cleaning the pelts of dead sheep with water and toxic chemicals.

[5] [wool scouring works location]

[6] Frances Pollon, The Book of Sydney Suburbs (North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1988), 164

[7] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 45

[8] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 45

[9] Frances Pollon, The Book of Sydney Suburbs (North Ryde, NSW: Angus & Robertson, 1988), 164

[10] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 45–46

[11] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 7

[12] There is a fantastic poster advertising this auction. See Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 9

[13] Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches A History, New South Publishing (Kensington: UNSW Press, 2014) 77

[14] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 51

[15] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 51

[16] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 8

[17] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 48–49

[18] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 15

[19] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 12–13

[20] For the camps that proliferated along Maroubra and indeed many of Sydney's beaches during the Depression years see Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches A History (Kensington: New South Publishing, UNSW Press, 2014), 90–96

[21] Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches A History (Kensington: New South Publishing, UNSW Press, 2014), 90–96

[22] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 26–27

[23] Randwick Municipal Council, The Bicentennial Commemorative Plaques of Randwick Municipality A Guide (Randwick, NSW: Randwick Municipal Council, 1990), 52

[24] Mark Scott and Tony Nolan, Maroubra: Golden Age of the Bra (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 2014), 11

[25] By 2010, Cronulla, North Narrabeen and Manly had also been formally gazetted as national surfing reserves Caroline Ford, Sydney Beaches A History (Kensington, NSW: New South Publishing, UNSW Press, 2014), 224

.