The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Redfern Park

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Redfern Park

Redfern Park [media]is bounded by Elizabeth, Redfern, Chalmers and Phillip streets, Redfern. Before Redfern Council resumed the site in 1885, the land was a dangerous 'pestiferous' bog known locally as Boxley's Lagoon. [1] The area was given as a land grant to Edward Smith Hall, the notorious editor of the Sydney Monitor, in 1822. Hall later sold his grant to the wealthy emancipist and merchant Solomon Levey.

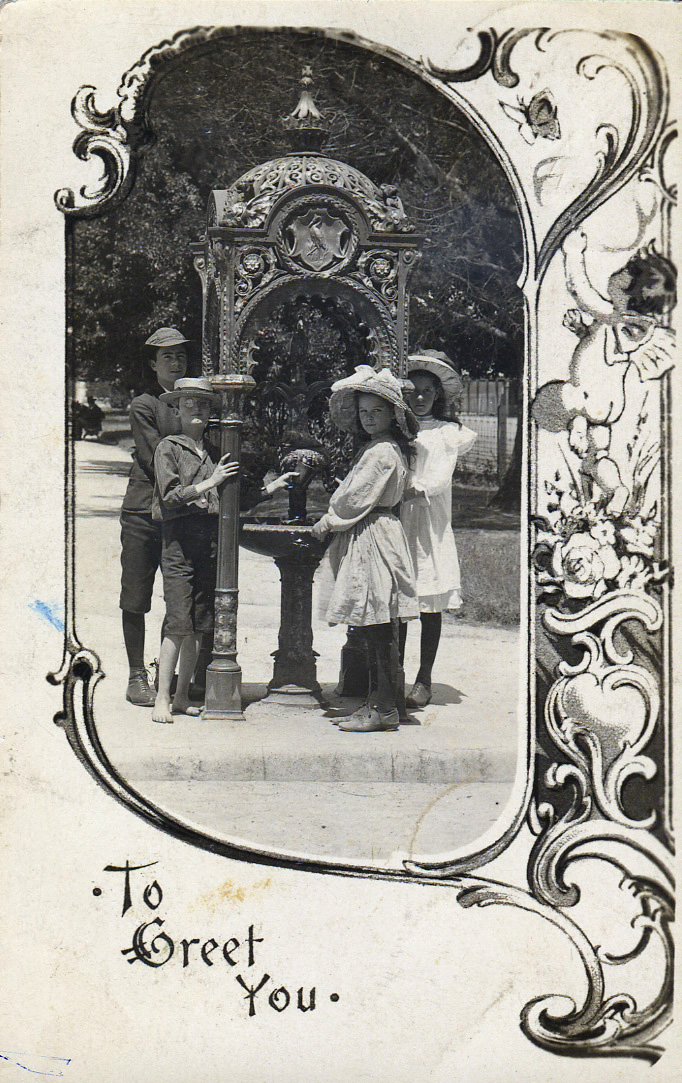

Due to the poor nature of the terrain little development took place in the next few decades. Yet the era of civic enhancement and municipal progress that prevailed in Sydney in the 1880s saw the site transformed and it was designed and constructed into a typical Victorian 'pleasure ground'. Ornamental gardens, exotic plants, fountains and walkways were established, together with cricket pitches, a bowling green and a bandstand. Redfern Oval was situated on the southern half of the park.

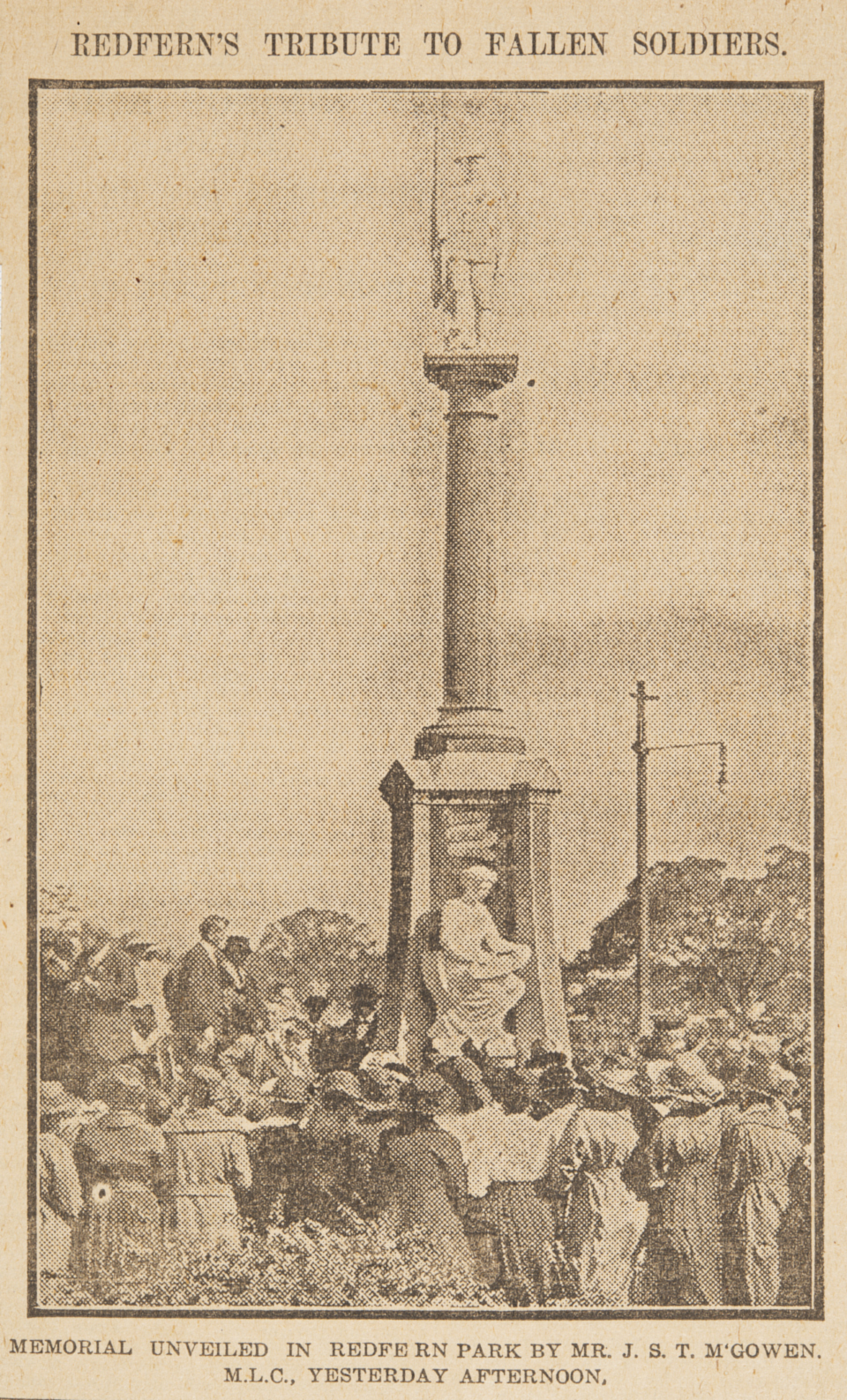

Local residents soon began to ask Redfern Council for permission to use the oval to play cricket and rugby union. [2] [media]A war memorial was erected in 1919 to commemorate the 137 local men who lost their lives during World War I. Today, Redfern Park is one of the most beautiful parks in inner Sydney, with fine mature trees including enormous fig trees and Canary Island palms, expanses of grass and historical monuments. It retains much of its Victorian character and provides a green oasis in Redfern. In 2014 Redfern Park was internationally recognised as one of the top parks in the world after receiving a prestigious Green Flag Award for recreation and relaxation. [3]

The site has particular significance for Aboriginal Sydneysiders.

Paul Keating's Redfern Address

Redfern Park [media]was the site of an important speech given by Prime Minister Paul Keating on 10 December 1992, to launch the United Nations' International Year of the World's Indigenous Peoples (1993). The Redfern Address, as it became known, was a defining moment in the nation's reconciliation with its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It was the first public acknowledgement by the Commonwealth Government of the dispossession of the first Australians. Keating spoke frankly and honestly of the land theft, dispossession, murder, violence and discrimination suffered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people in the course of modern Australia's creation. [media]As he stated:

The starting point might be to recognise that the problem starts with us, the non-Aboriginal Australians. It begins, I think, with an act of recognition. Recognition that it was we who did the dispossessing.

We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.

We brought the diseases and the alcohol.

We committed the murders.

We took the children from their mothers.

We practised discrimination and exclusion.

It was our ignorance and our prejudice.

And our failure to imagine these things could be done to us.

With some noble exceptions, we failed to make the most basic human response and enter into their hearts and minds.

We failed to ask – how would I feel if this was done to me?

As a consequence, we failed to see that what we were doing degraded us all. [4]

The choice of Redfern Park to deliver this speech was significant; Redfern had been the epicentre of Aboriginal (or more specifically, Koori) culture and activism, resistance and self-determination in Sydney for decades. As the Aboriginal activist Gary Williams had proclaimed 20 years previously in 1972, 'Redfern is the heart and Redfern is the community'. [5]

Keating's speech was delivered six months after the Australian High Court's historic and momentous Mabo decision, which confirmed that people living across the continent before the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 were indeed the traditional owners and occupiers of the land and that they had been for over 40,000 years. Mabo in effect dismantled and overturned the received understanding of land title predicated on the legal fiction of terra nullius.

Keating sought to reflect this important shift in official thinking. On that day at Redfern Park he spoke of a new partnership and the need for reconciliation. He acknowledged the remarkable contributions that Aboriginal Australians had long made to the nation's post-contact history; their central role in the frontier and exploration history of the continent, the dutiful part they had played as soldiers in the various overseas wars, and the enormous contributions they had long made to sport, art, literature and music. Yet Keating also spoke openly of the need for historians and history books to start acknowledging the resistance and resilience that the first Australians had shown throughout post-contact history. Later, Keating claimed that his speech was a 'fundamental act of recognition'. [6]

The Redfern address was a defining moment; ultimately it reflected a changing official interpretation of Australia's history. It put reconciliation firmly on the political, social and cultural agenda. It was also the first stepping stone for a later Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, to offer a formal apology to Indigenous Australians for past government practices and policies, which he delivered in Canberra in 2007. [7]

In 2011 ABC Radio National listeners voted Paul Keating's speech at Redfern Park as their third most 'unforgettable speech' of all time, behind Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream' speech and Jesus Christ's 'Sermon on the Mount'. Keating's speech was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia registry in 2010. [8]

Aboriginal art in the park

[media]Part of Keating's Redfern speech remains physically inscribed in the park today; an extract of the speech is included in Redfern Park's water sculpture Lotus Line by the acclaimed Aboriginal artist, sculptor, academic and activist Fiona Foley. In this sculpture, cast stainless steel and bronze lotus flowers stand beautifully strong, tall and proud, representing the strength of a colonised culture to survive. Foley created the sculpture specifically for children to run through.

Lotus Line forms part of a commission that Foley created for Redfern Park in 2008. Her subsequent installation Bibles and Bullets captured a sense of local Aboriginal history and culture and the enduring connections that remain with the land. Oversized seedpods are scattered among the ancient fig trees and provide play opportunities for young children. The fig traditionally played an important part in the Aboriginal diet. For older children, another component of Bibles and Bullets provides an intricate playscape telling the story of traditional possum hunting. [9] Poignant and yet educational, these sculptures attest to the importance of culture and land and the historical connections that lie within them. Today land, place and traditional culture remain of lasting and central significance for the Aboriginal community. Bibles and Bullets in Redfern Park is a symbolic and yet tangible acknowledgement of this connection. [10]

Redfern Oval

Redfern Oval adjoins Redfern Park. Here sport, politics, self-determination and a sense of cultural identity and community belonging have been entwined for Aboriginal people since the mid-twentieth century. The Aboriginal elder, Uncle Allan Madden, recalled how Redfern Oval on Saturday nights was 'a big meeting place' and 'full of blackfellers' during the 1960s and 1970s. [11] Here they would gather, sometimes to drink, sometimes to play an informal ball game, sometimes merely to continue the traditional practice of meeting together outside. It was a popular place for community leisure and a place to meet up. For other members of the Redfern Aboriginal community, however, Redfern Oval was where big plans for self-determination and Aboriginal autonomy were first discussed and made. It was here that an informal 'politics in the park' produced early ideas for the formation of the Aboriginal Medical Service and the Aboriginal Legal Service, which were both set up in Redfern in the early 1970s. [12]

Redfern All Blacks

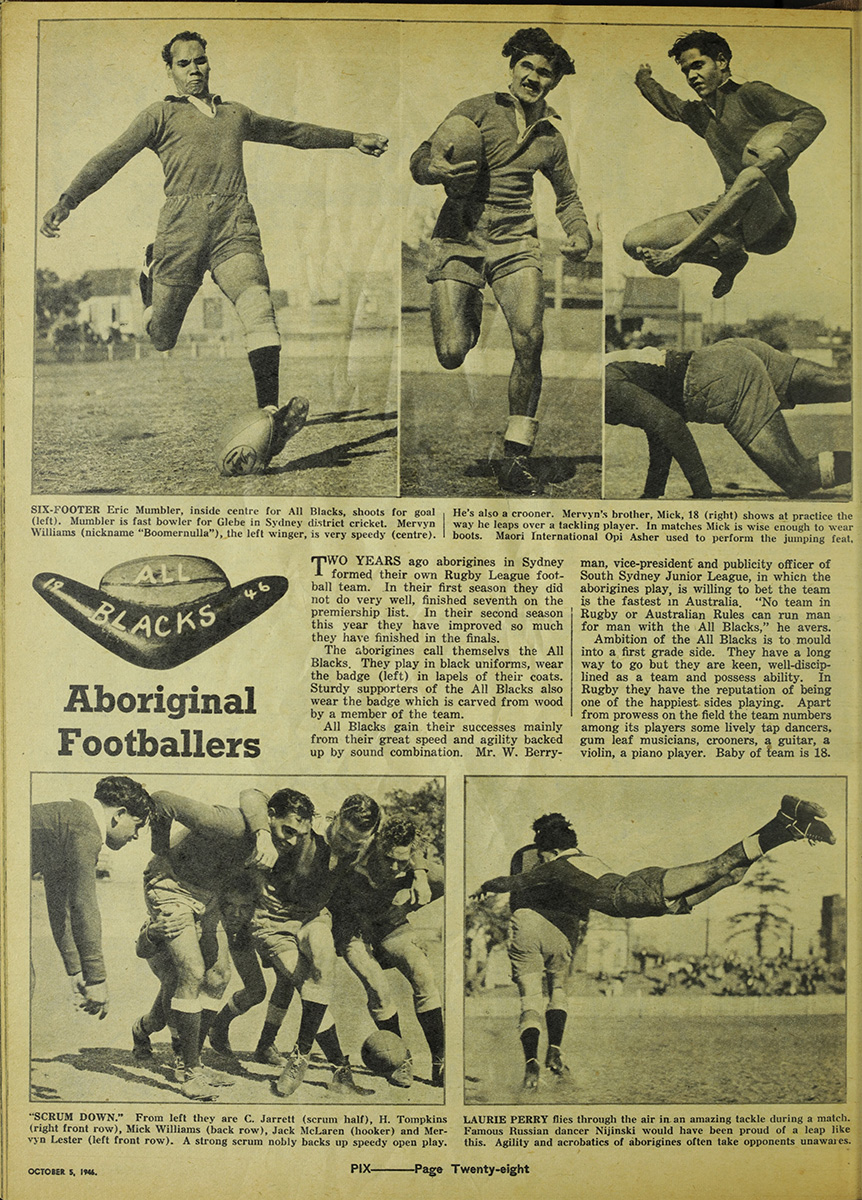

[media]Beyond politics however, Aboriginal sporting activities have a long history at Redfern Park. Cricket pitches and bowling greens were a feature of the original park in the 1880s; later, lawn tennis courts were introduced in the interwar years. Rugby League first arrived in 1911 and, in 1946, the South Sydney Rugby League Club adopted Redfern Oval as its home ground. The Redfern All Blacks team was officially formed in 1944 (some suggest it might have existed 'unofficially' for at least a decade before this) and it too trained at Redfern Oval. [13] The Redfern All Blacks is the oldest Aboriginal Rugby League club in Australia. From the very start, the team attracted talented Aboriginal players from around New South Wales, including Charles 'Chicka' Madden, Michael and Tony Mundine, Babs Vincent, Eric 'Nugget' Mumbler and Merv 'Boomanulla' Williams. Williams was one of the founding members of the Redfern All Blacks; 'Boomanulla' translates as 'speed and lightning', a trait the player was famous for on the rugby pitch. Indeed, the team provided many new role models and legends. [14]

[media]For Aboriginal people coming to Redfern after World War II, the Oval became a place where team sport and membership of the All Blacks provided a welcoming and inclusive place; a place that gave them a role, a sense of community and a positive sense of identity to help adjust to life in the city. Joining this all-Aboriginal club was, according to its secretary Ken Brindle, a clear 'expression of identity' and a means by which Aboriginal men could 'organise and manage their own affairs'. [15] During the 1960s and 1970s when Aboriginal self-determination without white interference was high on the agenda, the Redfern All Blacks played a prominent role. Rugby League continues to be important to the Aboriginal Redfern community today.

The Oval underwent a major redevelopment between 2007 and 2008 to provide world-class, modern training facilities for the South Sydney Rabbitohs NRL Football Club, Souths Juniors and Redfern All Blacks. The upgrade guaranteed a professional-level training ground for the teams, together with facilities such as change rooms, a weights room, meeting room and storage. The redevelopment also provided sporting, athletic and recreational opportunities for a broad range of local community, school and sporting groups, together with a new kiosk and a room for club and community use. [16]

Redwater Markets

Held in Redfern Park on the third Saturday of the month from 2009 to 2014, Redwater Markets were a further testament to the determination of the local Aboriginal community to achieve self-improvement and autonomy. The market's mission was to 'use community spaces and bring community life into Redfern Park', and all stall fees were used to support local community groups and projects providing opportunities for skills development and training. Redfern Park's markets were another clear expression of self-help and community action, showing the central place that a public park can provide for the wider social, cultural and political life of its community.

Place and belonging

Community and a sense of place and belonging are important and integral parts of everyday life for Aboriginal people living in Redfern. They have a strong and significant relationship with 'place'. Redfern Park provides a place to gather, to picnic, to barbeque, to play, to shop at the markets, or to simply reflect and remember. At Redfern Oval, supporting or playing for the local rugby league football teams is also part of belonging and a strong community identity. Both Redfern Park and Redfern Oval have meaningful significance for, and connections to, the social, cultural, political and historical lives of Aboriginal people, in the past (Barani), today and in the future (Barrabuga.)

References

Anderson, Kay. 'Place Narratives and the Origins of Inner Sydney's Aboriginal Settlement, 1972-73', Journal of Historical Geography 19 (1993).

Burnley, Ian and Nigel Routh, 'Aboriginal Migration to Inner Sydney' in Living in Cities; Urbanism and Society in Metropolitan Australia, edited by Ian Burnley and James Forrest, 199–211. North Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1985.

Clouston Landscape Planners. Redfern Park Plan of Management, June 1996, 2 vols .

Foley, Fiona, ed. The Art of Politics, the Politics of Art: The Place of Indigenous Contemporary Art. Queensland: Keeaira Press, 2006.

Foley, Gary. 'Black Power in Redfern 1968–1972'. The Koori History Website, 2001, http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/essays/essay_1.html

Foley, Gary and Tim Anderson. 'Land Rights and Aboriginal Voices' Australian Journal of Human Rights 12 (2006).

Hinkson, Melinda and Alana Harris. Aboriginal Sydney; A Guide to Important Places of the Past and Present. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2001.

Hartley, Jackie. 'Black, White …and Red? The Redfern All Blacks Rugby League Club in the Early 1960s' Labour History 83 (2002).

Kohen, Jim. 'First and Last People: Aboriginal Sydney' Sydney: The Emergence of a World City, edited by John Connell, 76–95. Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Plater, Diana, ed. Other Boundaries: Inner City Aboriginal Stories. Sydney: Jumbunna Aboriginal Education Centre, UTS and Leichhardt Municipal Council, 1993.

Read, Peter. '"The Evidence of Our Own Past has been Torn Asunder": Putting Place Back Into Urban Aboriginal History' in Exploring Urban Identities and Histories, edited by Christine Hansen and Kathleen Butler, 91–100. Canberra: AIATSIS National Indigenous Studies Conference, 2009.

Notes

[1] 'Redfern Park', City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/sydneys-history/people-and-places/park-histories/redfern-park, viewed 15 January 2015

[2] 'Redfern Park', City of Sydney website, http://www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/learn/sydneys-history/people-and-places/park-histories/redfern-park, viewed 15 January 2015

[3] 'Redfern Park flagged as first class', City of Sydney Media Centre website, 24 January 2014, http://www.sydneymedia.com.au/redfern-park-flagged-as-first-class/, viewed 15 January 2015

[4] Paul Keating's speech was delivered in Redfern Park on 10 December 1992 in the International Year for the World's Indigenous People. See 'Keating Speech: The Redfern Address', Australian Screen Online website, http://aso.gov.au/titles/spoken-word/keating-speech-redfern-address, viewed 11 January 2015

[5] Gary Williams (August 1972), cited in Kay Anderson, 'Place Narratives and the Origins of Inner Sydney's Aboriginal Settlement, 1972–73', Journal of Historical Geography 19 (1993): 320

[6] See Tom Clark, 'Paul Keating's Redfern Park speech and its rhetorical legacy', Overland, 213, 2013,, (https://overland.org.au/previous-issues/issue-213/feature-tom-clarke/, viewed 15 January 2015

[7] At the time, however, many Aboriginal activists were sceptical of the difference that the Redfern Park speech would actually make. See Gary Foley, 'Black Power in Redfern 1968–1972,' The Koori History Website, 2001, http://www.kooriweb.org/ foley/essays/essay_1.html, viewed 13 January 2015

[8] See Tom Clark, 'Paul Keating's Redfern Park Speech and its Rhetorical legacy', Overland, 213, 2013, (https://overland.org.au/previous-issues/issue-213/feature-tom-clarke/, viewed 15 January 2015

[9] 'Bibles and Bullets', CityArt, City of Sydney website, http://www.cityartsydney.com.au/artwork/bibles-and-bullets, viewed 15 January 2015

[10] For more on Fiona Foley's work see Louise Martin-Chew, 'Fiona Foley: Public and Political' in Artlink, 31, 2011, 62–65; Fiona Foley (ed) The Art of Politics, the Politics of Art: The Place of Indigenous Contemporary Art, (Queensland: Keeaira Press, 2006)

[11] Allan Madden, 'Redfern Oval was full of Blackfellers', interview on A History of Aboriginal Sydney website, http://www.historyofaboriginalsydney.edu.au/central/redfern-oval-was-full-blackfellers-allan-madden, viewed 13 January 2015

[12] Melinda Hinkson and Alana Harris, Aboriginal Sydney; A Guide to Important Places of the Past and Present (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2001), 84

[13] See Jackie Hartley, 'Black, White…and Red? The Redfern All Blacks Rugby League Club in the Early 1960s in Labour History, no 83, November, 2002, 151–52

[14] 'Redfern All Blacks', Sport and Leisure, Barani: Sydney's Aboriginal History website, http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/sites/redfern-all-blacks/, viewed 11 January 2015

[15] Ken Brindle, 'The Redfern All Blacks; A Club to be Proud of', New Dawn, June 1970, 2

[16] 'Redfern Park', City of Sydney website, www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/vision/better-infrastucture/completed-projects/redfern-park, viewed 15 January 2015

.