The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

William Chidley at Speakers Corner

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

William Chidley at Speakers Corner

[media]In 1874, following violent clashes between social reformers and the Irish Catholic community over the Irish Home Rule Bill, the New South Wales Government closed Hyde Park as a venue for public speaking. Speakers Corner in the Sydney Domain began in 1878, when Pastor Daniel Allen of the Particular Baptist Church in Castlereagh Street Sydney spoke there expounding his Baptist social reform ideals. Soon it became a place where the working people of Sydney could find entertainment and amusement on a Sunday, a day officially reserved for church and prayer alone. Speakers spoke on a wide variety of topics and the social issues of the day. From temperance to socialism, Darwinism to anarchism, interested and often impassioned crowds were soon a common sight on the grassy slopes. [1]

In the following decade Speakers Corner continued to provide a lively and popular outdoor venue. On the 24 January 1888, the Centennial supplement of the Sydney Morning Herald published an article on the Domain, noting:

The outer Domain is occupied on a Sunday afternoon by a dozen assemblies of the most diverse schools of religious thought, from the narrowest Calvinism to the most comprehensive latitudinarianism. They preach, argue, and wrangle a little noisily, perhaps, but with the greatest good humour, until tea time, and then go decorously home satisfied with having begun the week well. [2]

Moving into the early twentieth century, Speakers Corner in the Domain continued to play a dynamic role in the free expression of public opinion. Between 1914 and 1918 anti-conscriptionists, communists and socialists railed against the war, which they deemed a trade war for markets and the profiteers of capitalism. During the turbulent conscription referendum debates of 1916 and 1917, the Domain was crowded with thousands of people every Sunday. Indeed, the largest crowd in the Domain occurred during World War I when the then Premier of Queensland, Mr TJ Ryan, addressed an anti-conscription rally of an estimated 100,000 people. [3]

A self-educated eccentric

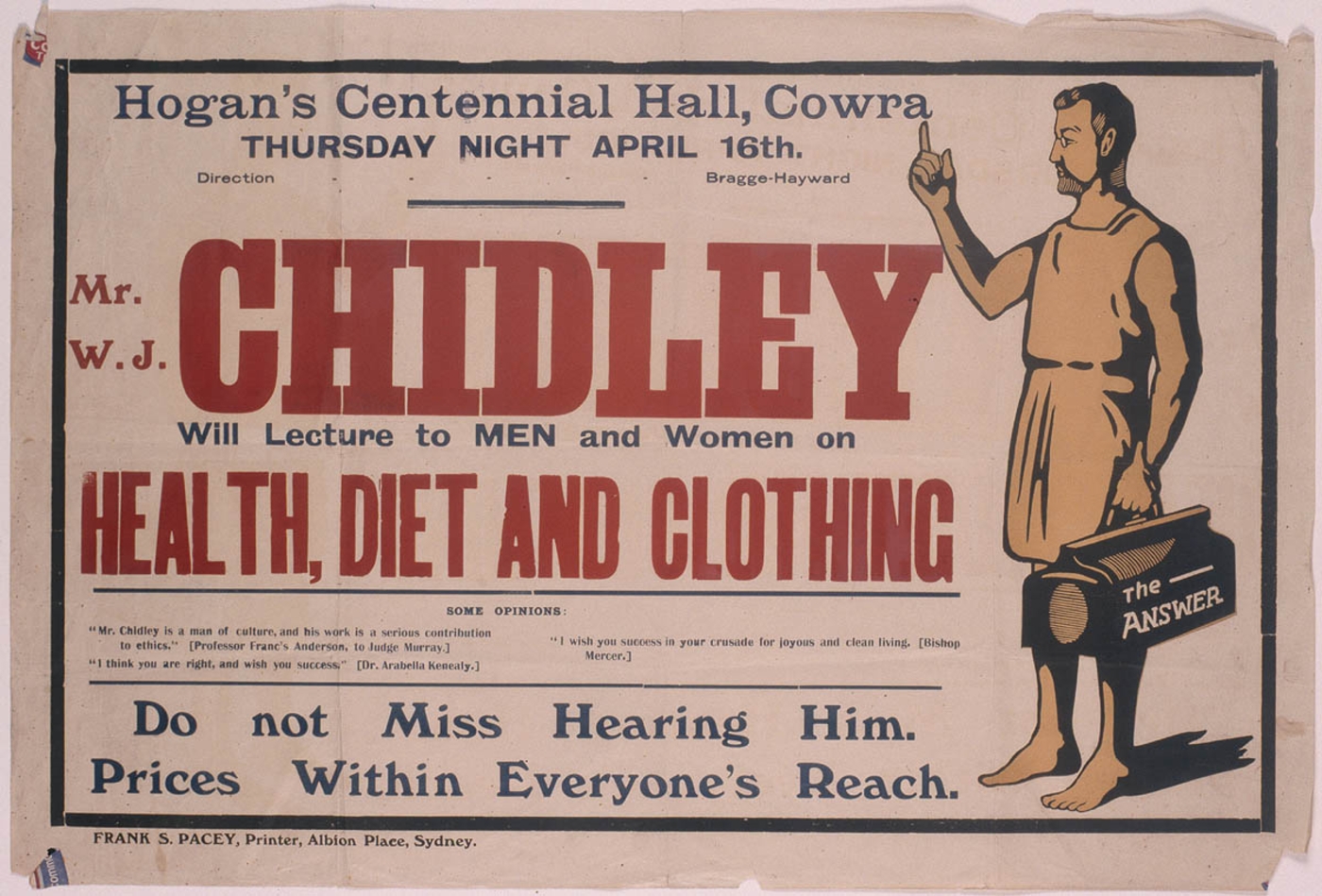

William James Chidley was one particular and regular speaker in the Domain during this time. A self-educated eccentric, Chidley – dressed in a simple tunic and sandals – preached a mantra of 'the simple life', advocating dress reform, a raw vegetarian diet and railing against modern day sexual relations and the subjection of women. For years he had been formulating a theory to deal with the inordinate amount of misery, illness, madness and degeneracy among people he knew. From his wide reading and an active but guilt-ridden sex life, Chidley developed the theory that there was something profoundly wrong with the way in which modern people had sex, saying it was unnatural. Sex, claimed Chidley, should only occur in the spring, outdoors in the sunshine, and only between two lovers. [4]

[media]Chidley believed that his scheme would someday save the world 'from all its misery, disease, crime and ugliness'. He also believed that it would save women from the pain and violence they all too often encountered during sexual relations. Indeed, his message constituted a radical critique of the prevailing sexual order, of the patriarchal conception of women's roles and duties in the provision of sexual services to men. And so, with a determined sense that his sexual theory was the answer to all the ills of mankind, he resolved to go on the active warpath and propagate it. By 1912, Chidley had become a familiar sight in the Domain, in the parks and on the streets of Sydney, lecturing on his theories and selling his pamphlet, The Answer. [5]

Chidley's scheme

In the early twentieth century, matters of a sexual nature were not mentioned in public or indeed in polite society. Rather, conventional morality demanded the sexual ignorance of women and children, while the state established public rituals (such as censorship) whereby it communicated an authorised version of public decency. These measures were publically justified as an effort to protect the working classes – especially women and children – from the threat of unspeakable depravity or corruption. Chidley's openness in espousing his sexual theories was seen as a threat to the social and civil moral order and 'his enemies detected in his ideas the ravings of a dangerous lunatic. But they also worried that the ignorant and impressionable might take them seriously.' [6] The frank discussion of sex and sexuality, all provoked an endless series of police prosecutions, gaol sentences and asylum incarcerations.

In Melbourne in 1911, booksellers distributing his pamphlet, The Answer, as well as Chidley himself, were prosecuted on the grounds that there were sections of the book which would 'tend to deprave and corrupt the morals of any person reading it'. [7] The court ordered the destruction of copies seized by police. This was not to be Chidley's last encounter with the establishment. Indeed, from his arrival in Sydney in 1911 until his untimely death in 1916, Chidley found his beliefs, behaviour and public speeches involved in a morality game of cat and mouse which involved his public followers, the police, the courts, the medical profession and the New South Wales Government itself.

A social and moral menace

Although regularly arrested and prosecuted – sometimes simply for wearing his unconventional tunic but more often for 'behaving in an offensive manner in the Domain' – the willingness of his many friends and supporters to pay his fines meant that the police were unable to prevent the determined sex reformer from continuing his agitation. After a number of public lectures, police threatened to prosecute any owner of a hall who leased him their premises. Yet Chidley still wandered the streets of Sydney and the Domain and the Royal Botanic Gardens, wearing his tunic and carrying his pamphlets. Crowds in the hundreds often flocked to the Domain to hear him speak. In August 1912, having been further outraged by Chidley's plan for a lecture to 'Ladies Only' the authorities found obliging doctors and arranged for him to be certified as insane and compulsorily detained in the Callan Park Mental Hospital for the insane. [8]

This was clearly an abuse of the law by the authorities in order to deprive a man who they deemed a menace to morality of his liberty. Yet many Sydneysiders rallied to his cause; public outcry erupted, meetings were held and deputations were sent to the Premier. [9] The New South Wales Government itself was divided over the issue. In parliament, fierce and lively debates over Chidley and the use and abuse of the law were reported in the daily press. [10] At a public protest meeting held at the Sydney Town Hall in August, such large crowds had gathered that The Sydney Morning Herald noted:

It is probable that even those who convened the meeting at the Town Hall last evening to protest against the incarceration in Callan Park of WJ Chidley, for some time past a conspicuous figure in the streets of Sydney, had no idea that their invitation would meet with such response. The meeting was called for 8 o'clock in the vestibule of the Town Hall, and a few minutes after that time there was not a seat to be had, and a notice "house full" was posted outside, to the disappointment of a crowd of about a thousand persons, who were addressed by way of an overflow meeting outside. [11]

Nationwide fame and support

Popular agitation against this blatant abuse of the law eventually led to Childley's release from Callan Park Mental Hospital in October 1912. Released conditionally, Chidley was to dress in 'appropriate attire' and not perform any public speaking, either indoors or out. Yet he quickly broke undertakings to dress in ordinary costume and to refrain from addressing meetings in public places. And for the next four years Chidley's life was characterised by the cycle of arrest, charge, incarceration and release. His charge sheet during these years was an impressive one. The majority of charges laid against him were of using indecent language in outlining his theories but the police also booked him for offensive behaviour, breaches of the Domain by-laws (usually associated with the sale of The Answer), using insulting words, obstructing the footway, behaving in a riotous manner, loitering on the footpath and attracting crowds in a public place.

Yet in their endeavour to silence the man and remove him from the streetscapes of Sydney, the authorities merely increased the public's awareness of him. Moreover, this awareness stretched across Sydney and out into the country at large. The nationwide fame of this eccentric yet harmless man, who regularly spoke his message of the simple life and gentle love at Speakers Corner, was really quite remarkable. From The Albury Banner and Wodonga Express to The Tamworth Daily Observer in northern New South Wales, to The Brisbane Courier and The Townsville Daily Bulletin in Queensland; from The Adelaide Daily Herald in South Australia to The Argus and The Ballarat Courier in Victoria, to The Mercury in Hobart and The Launceston Examiner in Tasmania, WJ Chidley, his message and his brushes with the law, regularly featured in newspapers across the whole country.

Ironically, in the quest to uphold public morality in outdoor public spaces, it was precisely at these very public sites that Chidley's supporters would often gather to protest against his treatment. When, in December 1913, he was again arrested and charged with insanity his supporters showed their own public defiance against the authorities by meeting in the Domain. As The Sydney Morning Herald noted:

A very large meeting in the Sydney Domain on Sunday afternoon was addressed by a number of speakers, of both sexes, who pleaded the cause of the release of W. J. Chidley. Last week Chidley was again arrested, and charged with insanity. Speakers declared that he was being persecuted. A petition to the Premier, Mr. Holman, is being prepared for Chidley's release, which was yesterday signed by 1000 people. Money was also promised to enable Chidley to be represented by counsel in the legal inquiry into his mental condition. [12]

The 'arbiters of public morality had long ago judged his opinions unfit for public consideration.' [13] Society, they believed, should not hear his eccentric and odd theories that the answer to all its social ills was the wearing of tunics, eating only fruit and nuts and sex in the springtime. Indeed it was the public airing of his views that so concerned the establishment. He was repeatedly told that holding these views in private was fine but it was his proselytising in the public spaces of Sydney that constituted him a social and moral menace.

Furthermore, much hostility to Chidley among doctors and the judiciary arose from his status as a layman addressing a popular audience on matters that the overwhelmingly male medical profession regarded as its prerogative and which they saw as dangerous if unleashed on 'the mob'. To his supporters, however, the issue was one of personal liberty, of freedom of speech and thought. Indeed much pro-Chidley agitation was not an endorsement of his theories but rather about defending the public discussion of sex as well as opposing using the lunacy laws to silence what the authorities deemed a public nuisance. As Mr Meagher told the meeting at Town Hall in August 1912:

What annoys the doctor most is that Chidley should be absorbed by an idea. I always thought that the man who had a theory and stuck to it was a man to be admired. Chidley is an original thinker, and has, therefore, a right of the freedom of his thought. (Cheers.) Our position is to get him released as soon as possible. No man should be put in an asylum unless he is a danger to himself or to others. [14]

Many different sections of Sydney's population supported Chidley. In July and August 1913, Chidley was encouraged by the interest and support offered by the Free Speech League. This organisation actively sought the approval of the government for a revised edition of The Answer that would be guaranteed against prosecution. No such guarantee was obtained. The seizure of Chidley's books from his home by police in 1914 occasioned protests from writers, academics, book sellers and printers, who moved an action against the new mode of censorship implied by the government's harassment of the sex reformer. The NSW branch of the Australian Writers and Artists Union was one of the first organisations to call for an investigation of his confinement in Callan Park. Chidley also appeared to have little difficulty finding Sydney booksellers to stock The Answer, in spite of police prosecutions on a number of occasions. [15]

Prominent radicals and socialists also supported him. In New South Wales, the Australasian Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World through their paper Direct Action, and the leading labour paper, The Worker, all readily opposed the persecution of Chidley. He also found overwhelming support from many women, both leading feminists and ordinary housewives. Rose Scott and Annie Golding were prominent supporters and, under Golding's presidency, the Women's Progressive Association was moved to protest against his treatment to the government. At the time, the role of women in the defense of Chidley was seen as a challenge to those males in authority (from the Premier to the local policeman) who had judged Chidley's lectures unsuitable for the ears of women. The very presence of women among the defenders was certainly an affront to such upholders of the patriarchal order. [16]

Struggle for liberty

On 16 February 1916, Chidley was again found insane and committed to Kenmore Mental Hospital for the insane at Goulburn. Backed by the Chidley Defence Committee, in June he appealed in vain to the Supreme Court. Again, there was considerable popular agitation by the press and in parliament for his release. George Black, the colonial secretary, granted Chidley leave of absence from Kenmore on bond, with the usual conditions but, as he was unable to refrain from 'inculpating' himself, Black had him recommitted in September. In October 1916, as Sydney furiously tore itself apart over the issue of conscription, some of his supporters came up with the idea of the government paying for him to go to either the United States or Canada. When the Consulate General of the United States was consulted, however, he replied that his government would regard any such initiative as an 'un-neighbourly act'. [17] Chidley recovered from a suicide attempt on 12 October but died suddenly of arteriosclerosis at Callan Park Mental Hospital on 21 December 1916.

Confessions

Chidley's lasting reputation must rest on his autobiography, The Confessions of William James Chidley. Although he intended no one to read them until after his death, in 1899 he sent the manuscript to the sexologist Havelock Ellis in London who used extracts in his Studies in the Psychology of Sex. In 1935, Ellis sent this manuscript to the Mitchell Library in Sydney, remarking, 'Not only is it a document of much psychological interest, but as a picture of the intimate aspects of Australian life in the nineteenth century it is of the highest interest, and that value will go on increasing as time passes'. [18] The Confessions of William James Chidley was first published in Brisbane in 1977. During 1980, No Room for Dreamers, a play about his life, directed by George Hutchinson, had a successful run in Sydney.

The struggle for Chidley's liberty was 'but a minor incident in the politics of New South Wales between 1912 and 1916'; [19] its significance rests ultimately in its exposure of the conflicts within that society over censorship and freedom of speech, morality, sexuality and the relations of the sexes. Furthermore, the singular story of Chidley, perhaps in microcosm illuminates the tensions that were produced by the public performance of free speech and times when freedom of speech was felt to be dangerous or subversive.

Throughout the twentieth century, Speakers Corner in the Domain would continue to be the site where these tensions were publically performed and enacted; where ideas of political conformity waged rhetorical war against political subversiveness; where religious orthodoxy battled polemically against anti-religious platforms, Rationalism and the early Free Thought Movement; and where notions of obscenity and immorality were measured by respectable ideals of decency and morality.

References

Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012

Willian James Chidley, The Answer, The Australasian Authors' Agency, Melbourne, 1911

Mark Finnane, 'The Popular Defence of Chidley', Labour History, no 41, November 1981

S Garton, Medicine and Madness: A Social History of Insanity in New South Wales 1880–1940, University of New South Wales Press, 1988

Bill Hornadge, Chidley's Answer to the Sex Problem: A Squint at the Life and Theories of William James Chidley and the Reactions of Society Towards His Unorthodox Views, Review Publications, NSW, 1971

Stephen Maxwell, The History of Soapbox Oratory, Standard Publishing House, NSW, 1994

S McInerney, The Confessions of William James Chidley, University of Queensland Press, 1977

Notes

[1] See Stephen Maxwell, The History of Soapbox Oratory, Standard Publishing House, NSW, 1994

[2] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 1888, p 2

[3] See Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War, Allen and Unwin, NSW, 2013; F Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia, Spectrum Publications, Melbourne, 1993; M McKernan and M Browne, (eds), Australia: Two Centuries of War and Peace, Australian War Memorial in association with Allen and Unwin, 1988

[4] Chidley thought the introduction of an erect penis into a vagina produced shocks to both men and women that led to their physical and mental deterioration. He believed that, under favourable conditions (outdoors, in Spring, between two lovers) the vagina would act as a vacuum and so draw the flaccid penis inside. As he explained in his 1911 pamphlet, The Answer, 'the crowbar has no place in physiology'. WJ Chidley, The Answer, The Australasian Authors' Agency, Melbourne, 1911

[5] See S McInerney, The Confessions of William James Chidley, University of Queensland Press, 1977; Bill Hornadge, Chidley's Answer to the Sex Problem: A Squint at the Life and Theories of William James Chidley and the Reactions of Society Towards His Unorthodox Views, Review Publications, NSW, 1971; Sally McInerney, 'Chidley, William James (1860–1916)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chidley-william-james-5579/text9519

[6] Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012, p 81

[7] Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012, p 81

[8] Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012, p 82

[9] See Mark Finnane, 'The Popular Defense of Chidley', Labour History, no 41, November 1981, pp 57–73

[10] Bill Hornadge, Chidley's Answer to the Sex Problem: A Squint at the Life and Theories of William James Chidley and the Reactions of Society Towards His Unorthodox Views, Review Publications, NSW, 1971, pp 60–65; S Garton, Medicine and Madness: A Social History of Insanity in New South Wales 1880–1940, University of New South Wales Press, 1988, p 63

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 August 1912, p 10

[12] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 December 1913, p 10

[13] Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012, p 149

[14] The Sydney Morning Herald, 20 August 1912, p 10

[15] Mark Finnane, 'The Popular Defense of Chidley', Labour History, no 41, November 1981, pp 63–64

[16] Mark Finnane, 'The Popular Defense of Chidley', Labour History, no 41, November 1981, pp 58–59

[17] Frank Bongiorno, The Sex Lives of Australians: A History, Black Inc, 2012, pp 149–50

[18] Quoted in S McInerney, 'Chidley, William James (1860–1916)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/chidley-william-james-5579/text9519, p xix

[19] Mark Finnane, 'The Popular Defense of Chidley', Labour History, no 41, November 1981, p 73

.