The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Women and World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Women and World War I

[media]Most historians have claimed that Australians unanimously supported the war on its outbreak in 1914. Certainly most people, politicians, the press and the pulpit felt great patriotic loyalty to England and the Empire and the first rush of 20,000 men to enlist was overwhelming. Many people thought the conflict would be over in a few short months. [media]For myriad reasons – a sense of duty, patriotism, loyalty, justice, or merely a desire for overseas adventure, many Australians did support involvement in the war. However, there were some Australians who opposed the war from the very start; politically active socialists, academics, Christian pacifists, Quakers, humanitarians and many leading feminists. Some lost their jobs, others their friends; some were assaulted and subject to violence for their views, others were sent to jail and then later deported. Women campaigning for peace and anti-conscription were not immune from violent and abusive behaviour. [1]

Female and feminist opposition to war

For some feminist women, militarism was just another version of the strong oppressing the weak and thus an emphatic form of patriarchy. For socialist feminists opposed to the war, it was both an issue of class and gender. Women played prominent roles in the anti-war, anti-conscription and peace movements that existed independently but sometimes overlapped between 1914 and 1918. They established women's organisations such as the Women's Peace Army and the Sisterhood of International Peace that later became the Australian chapter of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom and survives today. [2] They led and organised rallies, deputations and demonstrations and addressed outdoor meetings across the country.

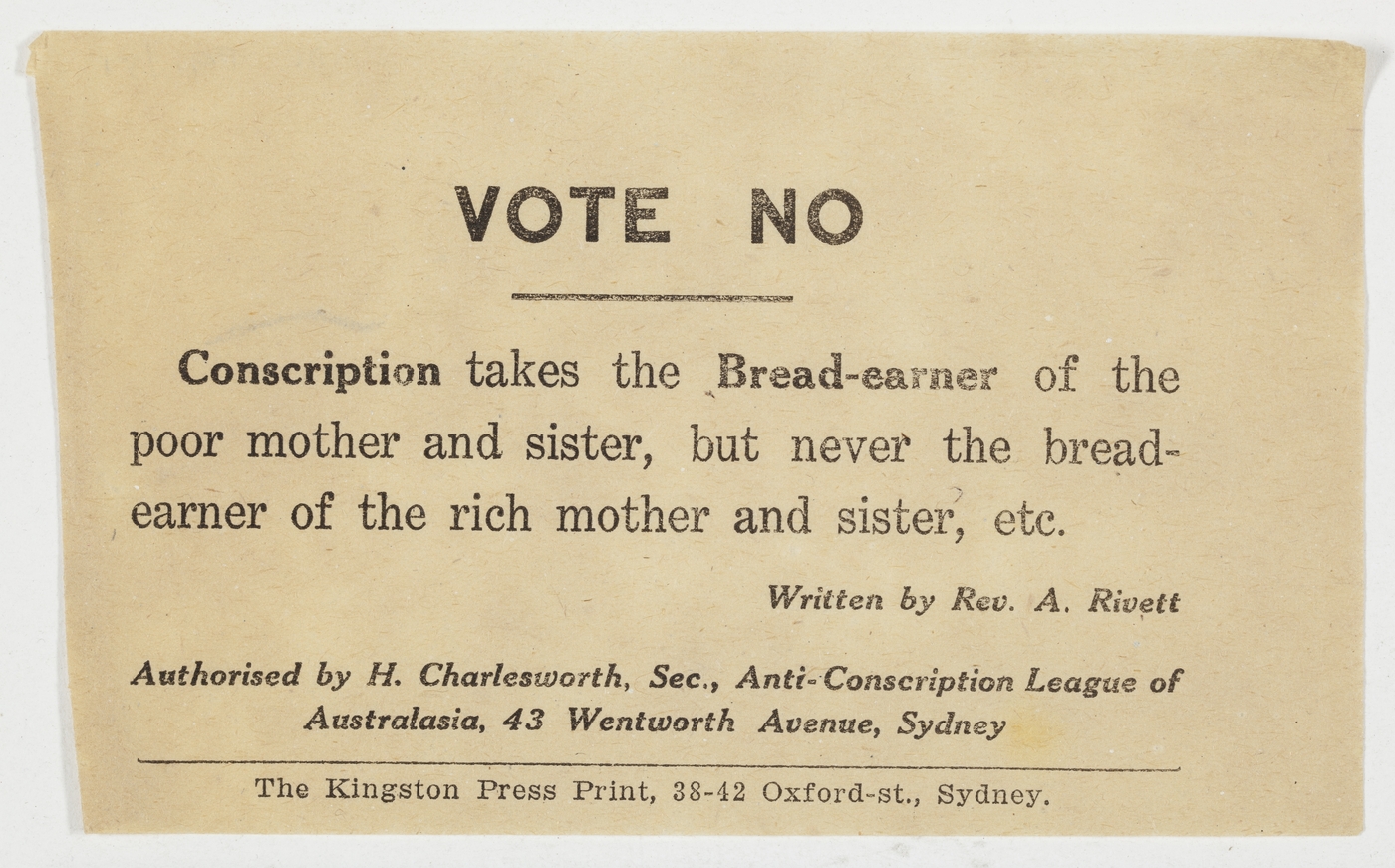

[media]Women who were members of socialist organisations naturally took a leading role in the anti-conscription campaigns and the anti-war movement. Jessie Lorimer was a member of the Socialist Democratic League of New South Wales and she regularly spoke in the Sydney Domain. From 1915 she agitated on behalf of the Anti-Conscription League of New South Wales, which was established in September that year. [3] Jennie Scott-Griffiths was an American who moved to Sydney in 1913. [4] She soon became a prominent figure in feminist, pacifist, labour and socialist organizations. From 1913 she was the editor of the Australian Women's Weekly and made regular contributions to The Worker. In March 1916 she wrote that women needed to challenge the political, social and economic conditions that male dominance in the public sphere had created – a world in which nations slaughtered the sons, lovers and husbands of women. [5] The same year she sat on the Women's Anti-Conscription Committee and joined with Vida Goldstein in the Women's Peace Army when a branch was formed in Sydney. [6] Their slogan was 'We War Against War'. [7] Like many others, Scott-Griffiths's anti-war and anti-conscription public lobbying cost her the editorial role at the Australian Women's Weekly and she was sacked in 1916. [8]

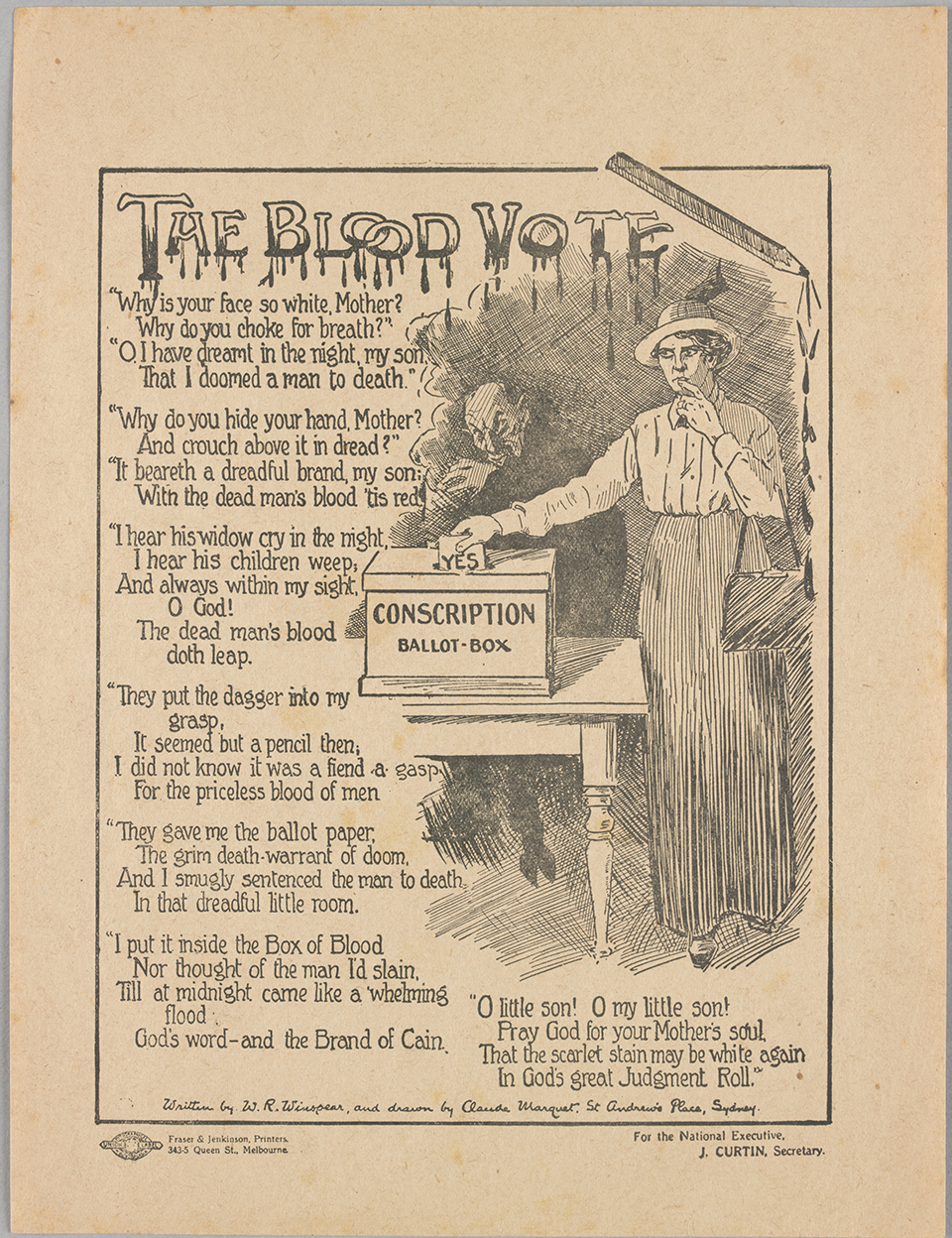

[media]Many women were strongly against conscription and opposed the war effort on the grounds that women, as mothers and the creators of life, had a moral obligation to preserve it. The anti-conscription pamphlet produced by the Women's Peace Army called 'The Blood Vote' appealed to the mothers of Australia to resist sending their sons to kill other mothers' boys. [9] This was a powerful poem and was hauntingly illustrated with a cartoon by Claude Marquet, the anti-war staff cartoonist at The Worker. [10] Marquet produced a prolific portfolio of political satire and protest but it was this sketch in particular that 'became the most famous effort of the campaign, which contained a veritable flood of cartoons and pamphlets.' [11] Vida Goldstein extended this appeal to mothers when she called upon women 'of all nations' to 'show their common bond of motherhood'. [12] The emphasis on a woman's motherly love, nurturing temperament and protection was encapsulated in the most common song that was sung at anti-conscription rallies, 'I didn't raise my son to be a soldier:'

I didn't raise my son to be a soldier,

I brought him up to be my pride and joy,

Who dares to put a musket on his shoulder,

To kill some other mother's soldier boy?

The nations ought to arbitrate their quarrels,

It's time to put the sword and gun away… [13]

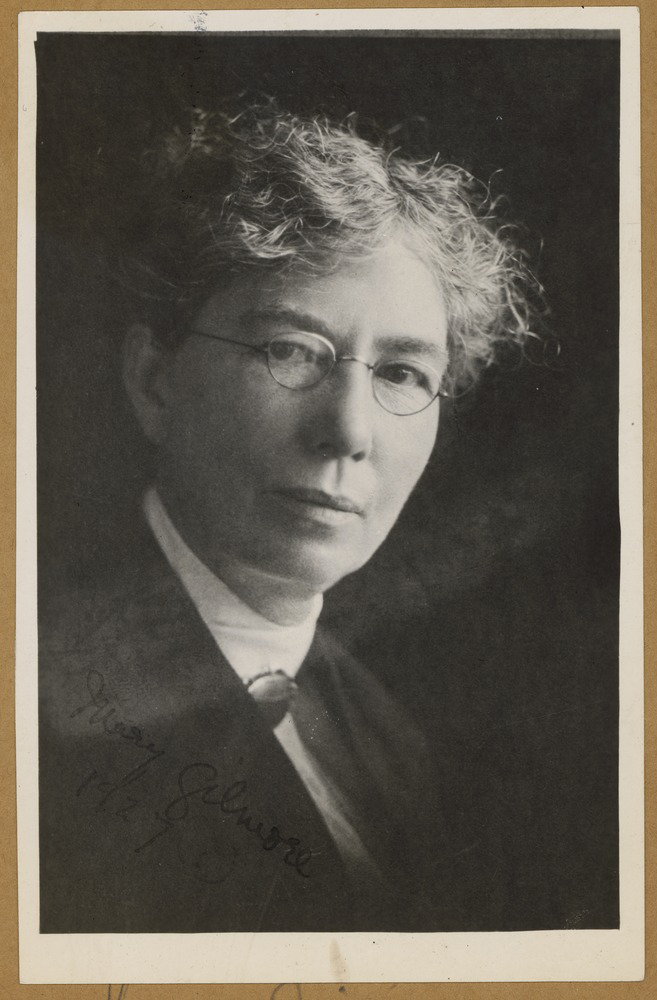

[media]Some women in their opposition to conscription and war were motivated by humane principles; reverence for all life and abhorrence at the violent destructiveness of war. Mary Gilmore's second volume of poetry The Passionate Heart written and published in Sydney in 1918 reflected her horrified reaction to World War I. These poems continued the 'women as mother' theme by contrasting the sorrow and heartache of war with the joys of motherhood. In 'The Measure' she passionately protested against the continuance of the slaughter and hatred engendered by war, the poem ending with the image of the mother suckling the child as the true measure of fundamental values. Likewise in 'These Fellowing Men', Gilmore laments the loss of so many splendid young men and again employs the mother analogy:

But oh they were so young, so young! Shine sun upon them where they lie, And storm and winter pass them by; And darkness, pleading to the earth for light, Lean over them – as mothers might, Lean over them and say Good-night! Goodnight! Dead are the young, the splendid young. [14]

After the war ended, Gilmore gave the royalties of this book to blinded soldiers and she also campaigned for land grants for returned servicemen. [15]

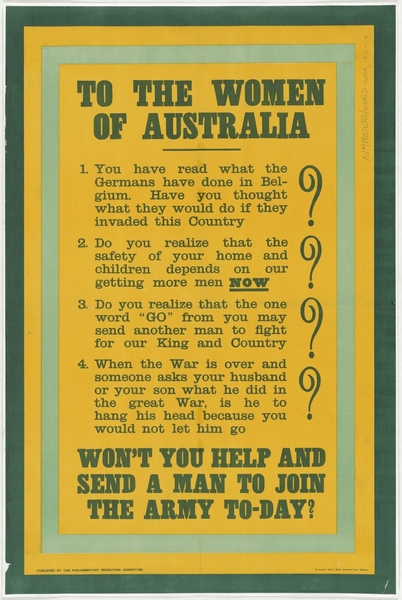

[media]Many women then opposed the war because they were the mothers, sisters and wives of young men facing near certain death on the battlefield. Yet women were also defined, and appealed to, because of their roles and relationships. The idea that it was a woman's duty to be prepared to sacrifice her male relatives was deemed by many Australians to be the height of womanly patriotism; it was also the best means by which women could greatly help the war effort. During the 1916 conscription referendum campaign, the Prime Minister, William Morris 'Billy' Hughes was convinced of the need for a steady supply of fresh reinforcements at the front. As volunteerism was not producing enough willing men he turned his appeal to the women of Australia. [media]He specifically issued a Manifesto to the Women of Australia in September 1916 in which he asked women as:

…mothers, wives, sisters of free men, what is your answer to the boys at the front? Are you going to leave them to die?...Now is your hour of trial and opportunity. Will you be the proud mothers of a nation of hero's, or stand dishonoured as the mothers of a race of degenerates? Prove that you are worthy to be the mothers and wives of free men. [16]

[media]Both pro and anti-voices then, used the politics of gender in their views, pitching the maternal, protecting and peace-loving woman against the loyal, patriotic and self-sacrificing mothers of heroes. The dichotomy was both stark and yet subtle. Today we have the diaries, poems and correspondence of prominent women of the period, both pacifists and war supporters, to shed light on what some women thought. It is, however, more problematic to imagine what most women felt or believed at this time. Many, it might be argued, found themselves stuck somewhere in the middle of two similar, and yet conflicting portraits of womanhood.

References

John Barrett, Falling In: Australians and 'Boy Conscription' 1911–1915 (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1979)

Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 2013)

James Bennett, Rats and Revolutionaries: The Labour Movement in Australia and New Zealand 1890–1940 (Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press, 2004)

Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (eds), Staining the Wattle: A People's History of Australia since 1788 (Fitzroy, Vic: McPhee Gribble, 1988)

Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993)

Charles Manning Hope Clark, New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, vol 6, A History of Australia (London; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

Joy Damousi and Marilyn Lake (eds) Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, UK; New York; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Eric Fry (ed), Rebels and Radicals (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1983)

Mrs Septimus Harwood, 'The Peace Society: Its Origins, Work, Difficulties and Mistakes' (paper read at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Peace Society, NSW Branch, Royal Society Hall, Elizabeth Street, Sydney December 13, 1921)

John F Hill, 'Vigour', Child Conscription, Our Country's Shame (Adelaide: Burmeister and Co, 1912)

Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968)

Marilyn Lake, Mark McKenna and Henry Reynolds, What's Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010)

Michael McKernan, Australian Churches at War: Attitudes and Activities of the Major Churches 1914–1918 (Sydney and Canberra: Catholic Theological Faculty and Australian War Memorial, 1980)

Michael McKernan, The Australian People and the Great War (Sydney: Collins, 1980)

Eleanor M Moore, The Quest for Peace: As I Have Known It In Australia (Melbourne: Wilke and Co Ltd, 1948–49)

The Peace Society, Pax: The Monthly Organ of the Peace Society

Australian Workers' Union, The Worker

Sydney Labour History Group, What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History (North Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1982)

Notes

[1] For a more detailed discussion of this see Joy Damousi, 'Socialist Women and Gendered Space: Anti-conscription and Anti-war Campaigns 1914–18' in Joy Damousi and Marilyn Lake (eds) Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, UK; New York; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 254–73. For an example of women who physically attacked other women who held opposing views of war, peace and conscription during this time see Raymond Evans, 'All the passion of our womanhood: Margaret Thorp and the Battle of the Brisbane School of Arts' in Joy Damousi and Marilyn Lake (eds) Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, UK; New York; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 239–53

[2] For the establishment of an Australian branch of the Sisterhood of International Peace, see Pax: The Monthly Organ of the Peace Society 32 (15 April, 1915): 7–9. The aims of the Sisterhood were 'to promote mutual knowledge of each other by the women of different nations, good will and friendship; to study the causes, economic and moral, of war, and by every means in their power to bring the humanising influence of women to bear on the abolition of war, and the substitution of international justice and arbitration for irrational methods of violence,' cited in Eleanor Moore, The Quest for Peace, As I Have Known it in Australia (Melbourne: Wilke and Co, 1948), 39

[3] The Anti-Conscription League of New South Wales was formed by trade union members and other socialist and left leaning groups to oppose conscription. Members were not necessarily anti-war (although many were) but they were opposed to compulsory enlistment. They were active in organising mass meetings in the Sydney Domain and illegally leafleting their cause. See Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 137–38

[4] TH Irving, 'Scott Griffiths, Jennie (1875–1951),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/scott-griffiths-jennie-11641/text20793, published in hardcopy 2002, viewed 27 February 2014

[5] Australian Worker (25 March 1916): 1

[6] Vida Jane Goldstein (1869–1949) was a well-known feminist, pacifist and socialist activist based in Melbourne. During the war her activities were closely monitored and her writings were censored See J Mulraney, 'Vida Goldstein' in Heather Radi (ed), Two Hundred Australian Women: A Redress Anthology (NSW: Women' s Redress Press Inc, 1988), 85–86

[7] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 105–06

[8] TH Irving, 'Scott Griffiths, Jennie (1875–1951),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/scott-griffiths-jennie-11641/text20793, published in hardcopy 2002, viewed 27 February 2014

[9] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 203–204. See Joe Harris, The Bitter Fight: A Pictorial History of the Australian Labor Movement (Brisbane: Queensland University Press, 1970), 239

[10] Vane Lindesay, 'Marquet, Claude Arthur (1869–1920),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/marquet-claude-arthur-7495/text13065, published in hardcopy 1986, viewed 27 February 2014

[11] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 203–04

[12] Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2013) 19–20

[13] Socialist (24 December, 1915): 1. The lyrics to this protest song were banned under the wide-sweeping powers of the War Precautions Act of 1915, however, this did not deter the women who would continue to sing it. Joe Harris, The Bitter Fight: A Pictorial History of the Australian Labor Movement (Brisbane: Queensland University Press, 1970), 236

[14] Mary Gilmore, The Passionate Heart (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1918), 3

[15] WH Wilde, 'Gilmore, Dame Mary Jean (1865–1962)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/gilmore-dame-mary-jean-6391/text10923, published in hardcopy 1983, viewed 27 February 2014

[16] William Morris Hughes, 'To the Women of Australia, Why They Should Vote Yes: Manifesto by Mr. Hughes,' The Mercury, 25 October, 1916

.