The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Maltese

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Maltese

Emigration has long acted as a safety valve for the overpopulated island-fortress of Malta. Consequently, the Maltese diaspora has expanded to lands far beyond the island's Mediterranean shores.

Before Malta became an industrialised, economically viable and independent nation in the mid-1960s, it could not sustain its high level of population, due to limited land space, a high birth rate and no natural resources. [media]Its main assets were its people – their skills, ingenuity, willingness to work hard, and thriftiness – qualities which emigrants quickly put to good use on arrival in Australia and elsewhere.

Today, many believe that Australians of Maltese birth and descent exceed the number of Maltese in the Maltese Islands themselves. The 2006 census for Maltese by ancestry in NSW stood at 61,528, of whom 49,169, or 80 per cent, reside in metropolitan Sydney. Today, among the top 30 languages spoken in NSW, Maltese ranks sixteenth. Second- and third-generation Australian Maltese are three times as numerous as the Malta-born population.

Early Maltese in Sydney

The Maltese community in Sydney is a long-established one, although little documentary research on the early colonial period exists. It is believed that the first convicts with distinctively Maltese names were two former private soldiers of the Royal Regiment of Malta, named Farrugia and Spiteri, who were convicted of desertion and transported to Sydney on the Admiral Gambier in 1811. However, the first definite evidence of a Maltese convict where the name and nationality are mentioned, found at the archives of St Mary's Cathedral in Sydney, refers to a 'Salvatore Diacono, of Maltese nationality', at Parramatta, west of Sydney, and dates back to 1821.

Within the colonial establishment, Rinaldo Sceberras was a Malta-born lieutenant in the British Army when he was sent to Sydney in 1837 with the 80th Foot Regiment. He was in charge of Wingello Stockade, some 50 miles (80 km) from Goulburn, which served as accommodation for the convicts constructing the Hume Highway, the main link between Sydney and Melbourne.

In 1882, a Maltese government official, Francesco DeCesare, on a fact-finding mission exploring subsidised migration to Australia and New Zealand, mentioned eight names in his report 'as a list of Maltese met at Sydney where they are settled since several years'.

Maltese settlement in the early twentieth century

Maltese settlement in Sydney grew around two precincts, namely Woolloomooloo and Pendle Hill. Woolloomooloo tended to attract those from urban areas in Malta, who found employment on the wharves, on fishing boats and in shops and restaurants close to the city centre. In the early years, immigrants from villages in Malta and Gozo tended to gravitate to the Parramatta area, particularly around Pendle Hill, which earned the name of 'Little Malta'.

In 1916–17, 208 British subjects from Malta were refused entry to Sydney after being subjected to a dictation test in Dutch, under the terms of the Immigration Act, which allowed potential immigrants to be tested in any European language. Caught up in the conscription and White Australia controversy of the time, the passengers on the Gange spent time in New Caledonia and on a hulk in Berrys Bay, Sydney, before eventually being allowed into Australia. The New South Wales Governor, Sir Gerald Strickland, himself Malta-born and later Prime Minister of Malta, worked behind the scenes for the men's release.

Postwar migration from Malta

The peak of Maltese migration to Australia in the post-WWII era occurred in the mid-1950s and 1960s. [media]The first postwar ship to reunite families who had been unable to return to Australia from Malta due to the outbreak of World War II was the Rangatiki, which arrived in February 1946. Carrying 64 Maltese passengers, it was a troopship not yet converted for carrying migrant families.

Two years later, in May 1948, an Assisted Passage Agreement was signed between the governments of Australia and Malta, which extended the benefit of subsidised travel costs to thousands of Maltese.

Later settlement took place in different parts of metropolitan Sydney, and Maltese are to be found in all municipalities, shires and cities of metropolitan Sydney. Today, the majority reside in western Sydney, where four local government areas (Blacktown, Holroyd, Parramatta and Baulkham Hills) contain one out of every four of the Maltese-by-ancestry. The present trend of Maltese distribution in Sydney shows a decline in inner city areas, with a growing presence in outer areas of Sydney, such as Penrith, the Hawkesbury region, Campbelltown, Camden and Wollondilly.

A similar pattern is revealed in the Illawarra region, where the Maltese are moving out of the City of Wollongong to suburbs in the Shellharbour, Shoalhaven and Kiama local government areas. One new phenomenon of Maltese distribution is their move to areas attractive to retirees, such as the Central Coast. For example, the number of Malta-born people in Gosford/Wyong in 1976 stood at 121; this had grown to 612 in 2006.

The Maltese community

Today, there are a number of Maltese associations in Sydney, which cater for the recreational, sporting, religious, cultural and social needs of their members. A number are linked to the Maltese Community Council of NSW, an umbrella body which coordinates the activities of affiliated associations and acts as the community's advocate with the Maltese and Australian governments. The Maltese Community Council of NSW holds a number of functions of national or community significance.

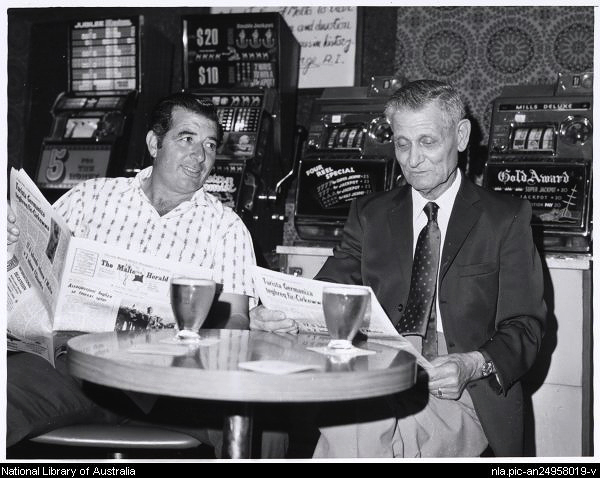

[media]Some pioneer Maltese associations in Sydney which were very active in the immediate postwar years include the Phoenician Club of Australia, which ceased to exist in 1998 but which, for many years, was the first and only Maltese licensed club in Sydney, and the Maltese Guild of Australia (NSW) founded in 1953 and now defunct: its focus was the inner suburbs of Sydney.

Being predominantly Catholic, the Maltese community has many members who are active in parish work, scripture teaching and charitable activities. The Capuchins, Carmelites, Dominicans and Salesians were among the early religious orders to service Maltese migrants. These were followed in postwar years by the Missionary Society of St Paul, Franciscan Conventual, a number of diocesan priests (particularly Father William Bonett in NSW) the Dominican Sisters of Malta, the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, the Augustinian Sisters and the Franciscan Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

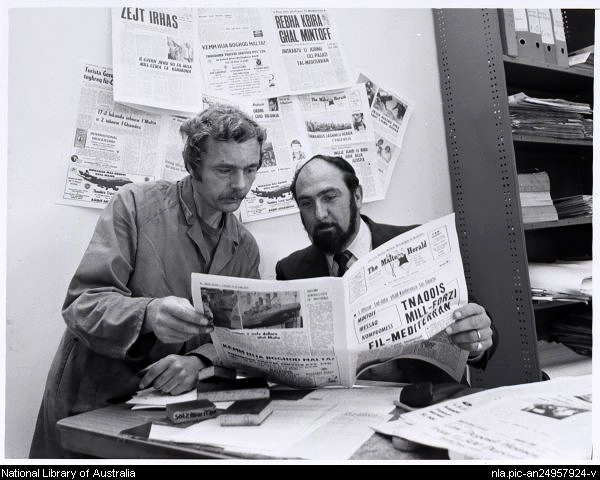

[media]The Maltese community has a national, weekly bilingual newspaper, The Maltese Herald , founded in 1961 and based at Merrylands, which provides the community with local and overseas news, and disseminates social and welfare information within the Maltese community in all states of Australia. It is the oldest continuous Maltese newspaper outside Malta.

Sport

Soccer attracts a huge following within the Maltese community. The main soccer club is the Parramatta Melita Eagles Sports Club Ltd, formed in 1956, which has its own home ground, Melita Stadium at South Granville. It participates in the NSW Super League and fields teams in the NSW Youth League and Granville District Soccer under the name PCYC Parramatta Eagles. The club is actively involved in the development of youth and junior soccer in the Parramatta region. Parramatta Melita Eagles holds regular social functions and has a Maltese restaurant and indoor sports facilities. A new development in Maltese sporting culture has been the formation by Australian-Maltese of the Maltese Rugby League Association in 2004.

Maltese-Australians enjoy strong links with their homeland, enhanced through reciprocal government agreements on social security, health, taxation, dual citizenship and working holidays. Many individuals of Maltese descent contribute to mainstream Australian society in diverse areas of business, primary production, politics, sports and elsewhere according to their expertise.

The Maltese community in NSW is old and established, with associations forming an infrastructure for activities and services. Its main concerns for the future relate to the ageing of its members and the maintenance of language and cultural heritage among the growing second- and third-generation Australian Maltese community.

References

Barry York, Maltese in Australia, Victoria University of Technology, Melbourne, 1998

Barry York, 'The Maltese Ship', National Centre for History Education, http://www.hyperhistory.org/index.php?option=displaypage&Itemid=731&op=page#art, accessed 21 January 2008