The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Clint, Alfred

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Clint, Alfred

Alfred Clint came of an English artist family. His grandfather was portraitist George Clint ARA (1770–1839) and his father, marine painter and scenic artist Alfred Clint (1807–1883) was one of George's four artist sons. Among Alfred's achievements, he was briefly the President of the Incorporated Society of British Artists.

Sydney's Alfred Clint was one of Alfred Clint senior's five sons, born in London on 28 August 1842. There was a family connection with the Australian colonies, for another of George's sons, Raphael, an engraver, lithographer and miniature painter, had come to Western Australia in 1829. He died in Sydney in 1849, when his nephew was seven years old.

Alfred Clint came to Australia as a young man in the mid-1860s. He worked first as an assistant scene painter to John Hennings at the Theatre Royal in Melbourne. He contributed to a production of Anthony and Cleopatra, but his work was often in pantomime. In 1867 he painted settings for Tom Tom the piper's son: and Mary Mary Quite Contrary, which played during the Royal visit by Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh. Clint then worked briefly in Adelaide, before coming to Sydney in 1869 accompanying a production of Boucicault's After Dark.

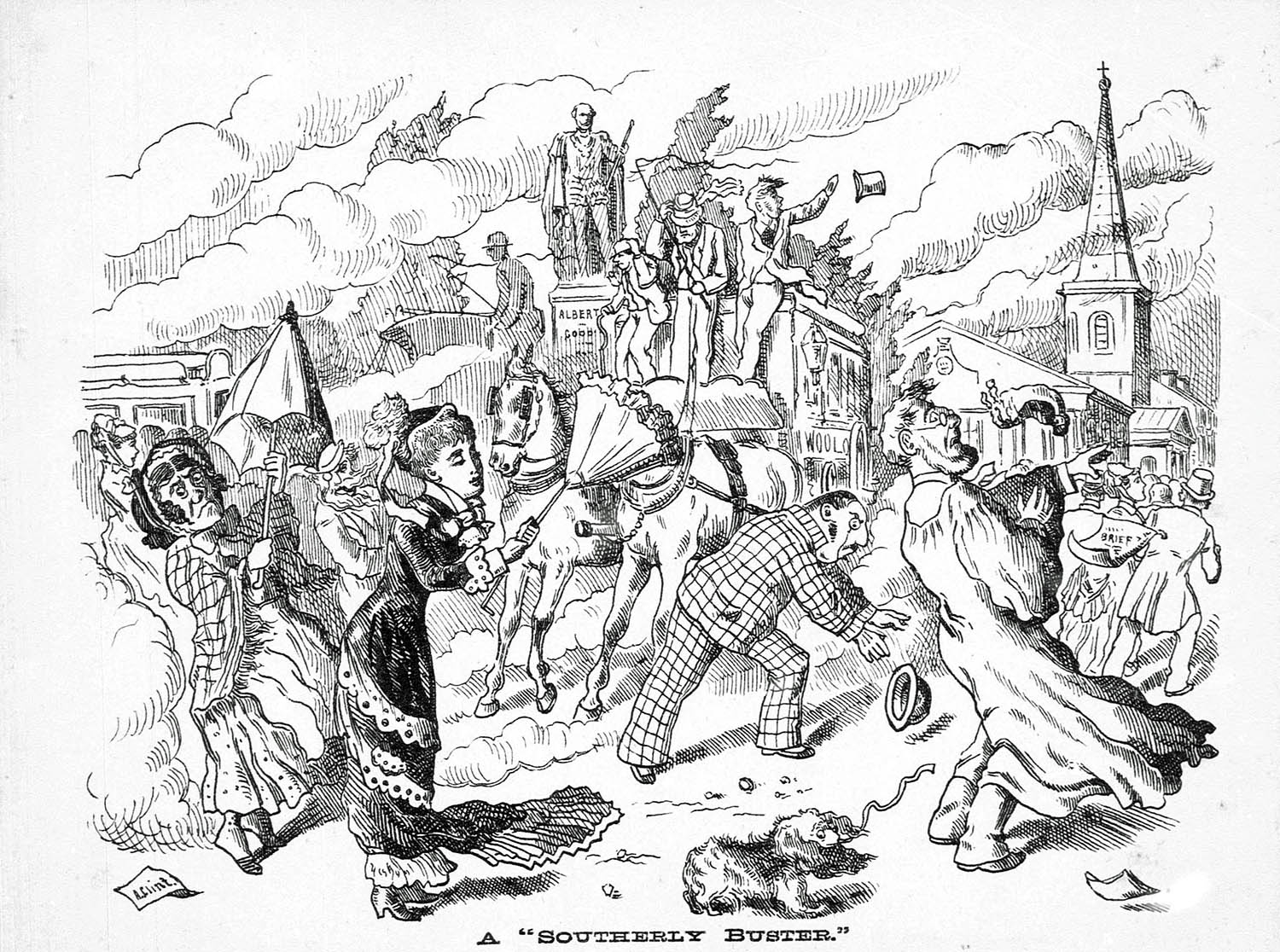

[media]Clint was a talented artist with a broad range. He was an original member in New South Wales of the Royal Art Society and one of the founders of the Sketch Club. He was a fine water colourist with a delicate touch. On arriving in Sydney in 1869 he also joined the staff of Sydney Punch as a cartoonist, working in black and white, and later worked on the early issues of the Bulletin. It was his theatre scene painting, however, which provided both his living and his reputation.

The art of the scene painter was a valued one in the nineteenth century, and the practitioner had a gruelling apprenticeship of seven to nine years in the theatre. These artists were expected by their audiences to fulfil a growing public desire for verisimilitude in theatrical representation in contrast to the stylistic images of previous theatre fashion. Victorian audiences wanted naturalistic stage action and enterprising local managers wanted local colour. Thus the scene painter provided a visual performance. The artists worked on site, often in hazardous conditions, using tall ladders and a bosun's chair to cover large hanging canvases. These giant pictures were for many viewers, particularly in colonial society, the only way to experience paintings first hand, before there was easy access to public art galleries.

On his arrival in Sydney, Alfred Clint was immediately appointed scenic artist at Sydney's Prince of Wales Theatre. For his first staging there, WH Hoskins' production of The Tempest, Clint designed and painted nine scenes, including two spectacular sea scenes. One was of waves moving on a rocky shore, and another featured Juno and the Graces. Clint also contributed a feature scene, that of the 'exterior of post office', Colonial Architect James Barnet's newly completed Sydney edifice, to the 1871 Christmas pantomime The House that Jack Built. This show, originally focussed on Melbourne, was a localised spectacular celebrating 'the foundation and progress of Australia'.

Clint also worked at the Royal Victoria, Her Majesty's, the Opera House and the Criterion, where his history painting of the landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay formed the act drop at the theatre's opening.

Much of his work, however, from the early 1880s to the late 1890s, was for George Rignold's management, where he provided settings for WH Cooper's Sun and Shadow, George Darrell's production of Transported for Life and Luscombe Searelle's comic operas Bobadil and Isadora. In all these productions, his scenery was greatly admired.

Clint remained in Sydney for the rest of his life. In 1872 he married Mary Jane Lake, the daughter of Thomas and Mary Ann, and they settled in Balmain. The Clints had three sons, Alfred Thomas, born in Sydney 26 January 1879, George Edward, born 1884, Sydney Raphael, born 1893 and at least one daughter, Mary Ethel, born in 1881. The couple may have moved to Burwood later on in life, for Mary Jane Clint died there in 1918.

All three sons became artists and scene painters, apprenticed to their father. In 1919 they established Clint's Art Studios at 63 Grose Street, Camperdown. Alfred Clint, however, only lived four years more. He died aged 82 on 20 November 1923. He had moved earlier (perhaps after the death of his wife) to live with his eldest son, Alfred Thomas and his family in Fitzgerald Street, Windsor. Both father and son were well-known for their delicate landscape watercolours of the Hawkesbury district, and were frequent exhibitors at local art shows. Alfred Clint's funeral was held on Wednesday, 21 November 1923 at Rookwood Cemetery where he is buried in the Church of England section. [1]

At least two of his sons, Alfred Thomas and Sydney Raphael, carried on the business of Clint's Art Studios but it was increasingly unviable. The craft of the scene painter did not survive the coming of movies and the economic depression of the late 1920s. Both men died young, Sydney in 1930, aged only 37, and Alfred Thomas, suffering from Parkinson's disease, aged 57 in 1936. George Edward survived them until 1952. The scene painting business did not.

References

Anita Callaway, Visual Ephemera , University of New South Wales Press, Kensington NSW, 2000, pp 57, 165, 173

HJ Gibney and A Smith, A Biographical Register 1788–1939, 2 vols, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Canberra, 1987

Eric Irvin, Dictionary of the Australian Theatre 1788–1914, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1984, p 71

Brian Jones, The Art of Alfred T. Clint, Hawkesbury City Council, Windsor NSW, c 1998

Philip Parsons (gen ed) with Victoria Chance, Companion to Theatre in Australia (Currency Press in association with Cambridge University Press, Paddington, 1995, pp 150–1, 546–8

Notes

[1] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 November 1923, p 11; Adelaide Advertiser, 22 November 1923, p 12

.