The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Alexander

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Alexander

The Alexander was the largest and most notorious convict transport in the First Fleet. During its eight-month voyage to Botany Bay in 1787–88, under Master Duncan Sinclair, the 452-ton barque carried around 25–33 crew and 195 of 'ye worst of land-lubbers'. [1]

The greatest villains

[media]Before the convicts boarded, Arthur Phillip noted:

The sooner the crimes and behaviour of these people are known the better, as they may be divided, and the greatest villains particularly guarded against in one transport. [2]

In the end, Alexander was one of two all-male convict transports.

On 4 January 1787 the first of convicts arrived at the ship at Woolwich Docks, however, they were unable to board because most were too sick to move from the prison hulk to the ship. Two days later, Alexander loaded 184 prisoners from Newgate Prison, including the most notorious convicts in the fleet. Among them was John Powers, who later attempted to escape and John 'Black' Caesar, a well-built Malagasy who would later wound the Aboriginal warrior Pemulwuy, assault and steal in the new colony and become Australia's first bushranger. [3]

In the same month, authorities 'found the convicts to be very troublesome and could take their hands out of irons'. [4] First Lieutenant William Bradley ( HMS Sirius) reported they were:

…handcuff'd two together or had chains on, those that were handcuffed were never seperated [sic] but obliged to move together upon all occasions. Between decks, in which these People were confined was guarded by a strong Bulk head abaft with loop holes & filled with nails… [5]

During the five months they waited for departure, sixteen prisoners died from the effects of a piercing cold English winter and a lack of fresh air. [6]

The voyage

[media]The ship was delayed at Tenerife until May 13 when marine Richard Asky was found intoxicated at his post [7] and the crew refused to sail until their wages were paid. This incident and the fact that the crew and some of the convicts were busy victualling provided the distraction convict John Powers needed to make his escape. Surgeon White recounted:

During the night, while the people were busily employed in taking in water on board the Alexander…one of them, of the name of Powel [sic], found means to drop himself unperceived into a small boat that lay along-side; and under cover of the night to cast her off without discovery. [8]

After failing to join a Dutch ship, Powers rowed himself to a small island where he was found the following morning and returned to Alexander in irons, just in time for the fleet's departure.

[media]On 18 July, Surgeon White investigated reports of sickness on Alexander and concluded the cause was the bilge water. He found:

…the illness complained of was wholly occasioned by the bilge water, which had by some means or other risen to so great a height that the pannels of the cabin, and the buttons on the clothes of the officers, were turned nearly black by the noxious effluvia. When the hatches were taken off, the stench was so powerful that it was scarcely possible to stand over them. [9]

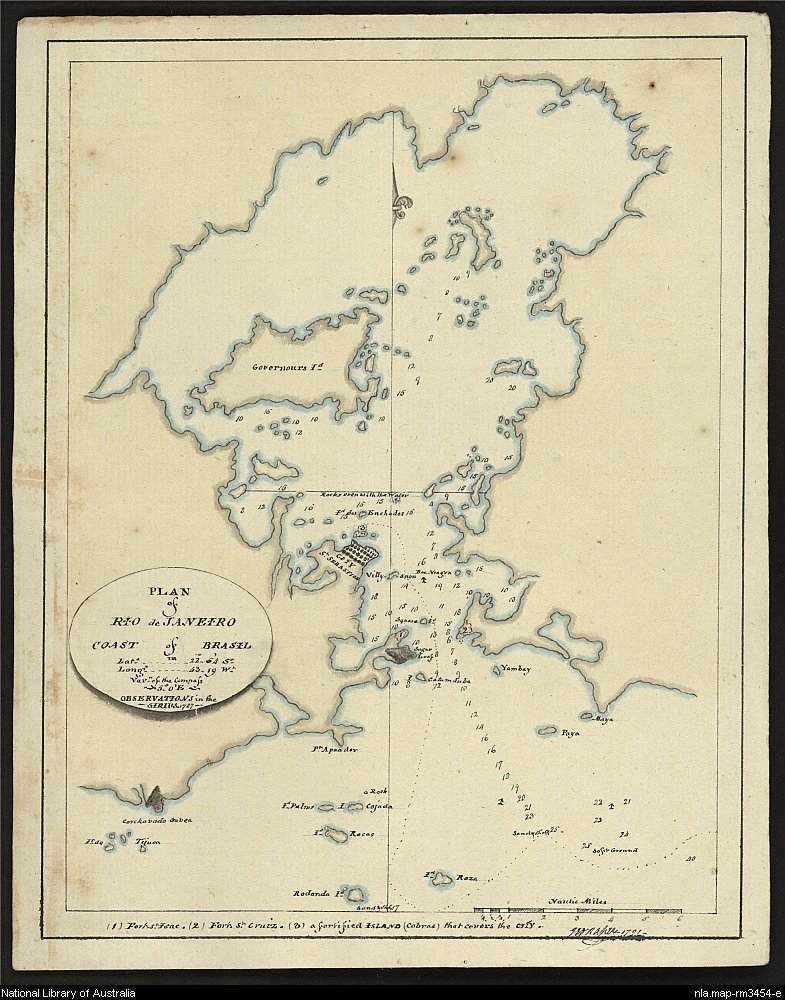

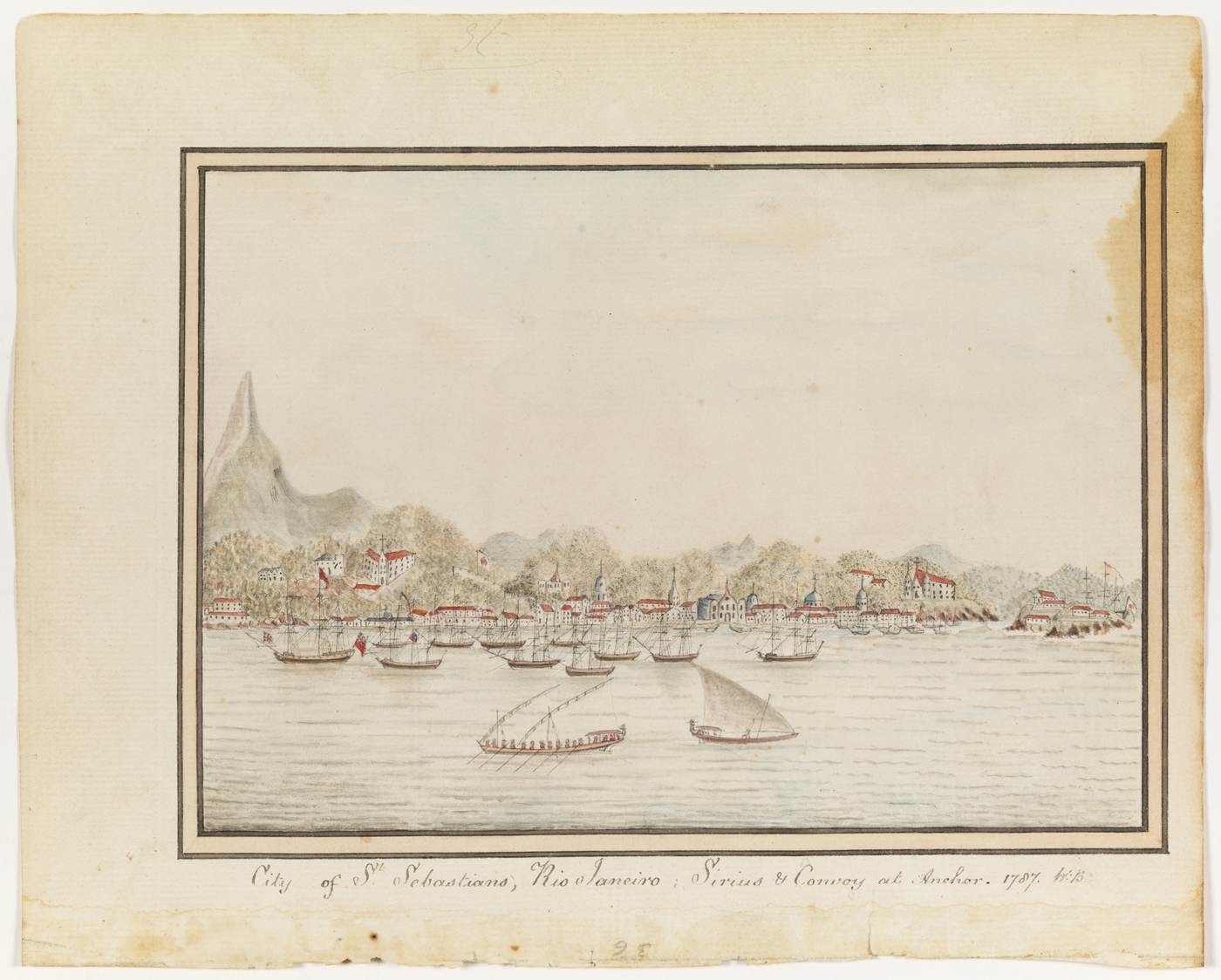

[media]Shortly before anchoring at Rio de Janeiro, Alexander lost a convict overboard after he fell from the spanker boom and could not be rescued. [10]

After Captain John Hunter and Major Robert Ross boarded Alexander to 'settle the convicts', the fleet left Rio on 4 September. On 6 October, convicts caused a disturbance on the ship. Bradley claimed the mischief was led by John Powers who, with the assistance of four of the crew and armed with knives, pistols and iron crows (crowbars), planned to escape at their next port of call. [11] One of their gang betrayed the plan to Sinclair who alerted the marines and signalled Sirius. [12] They were sent to Sirius, Powers put in irons and the four crew set to work under close watch. The fleet spent a month at Cape Town and set sail for the final leg of the voyage on 12 November. [13]

The arrival

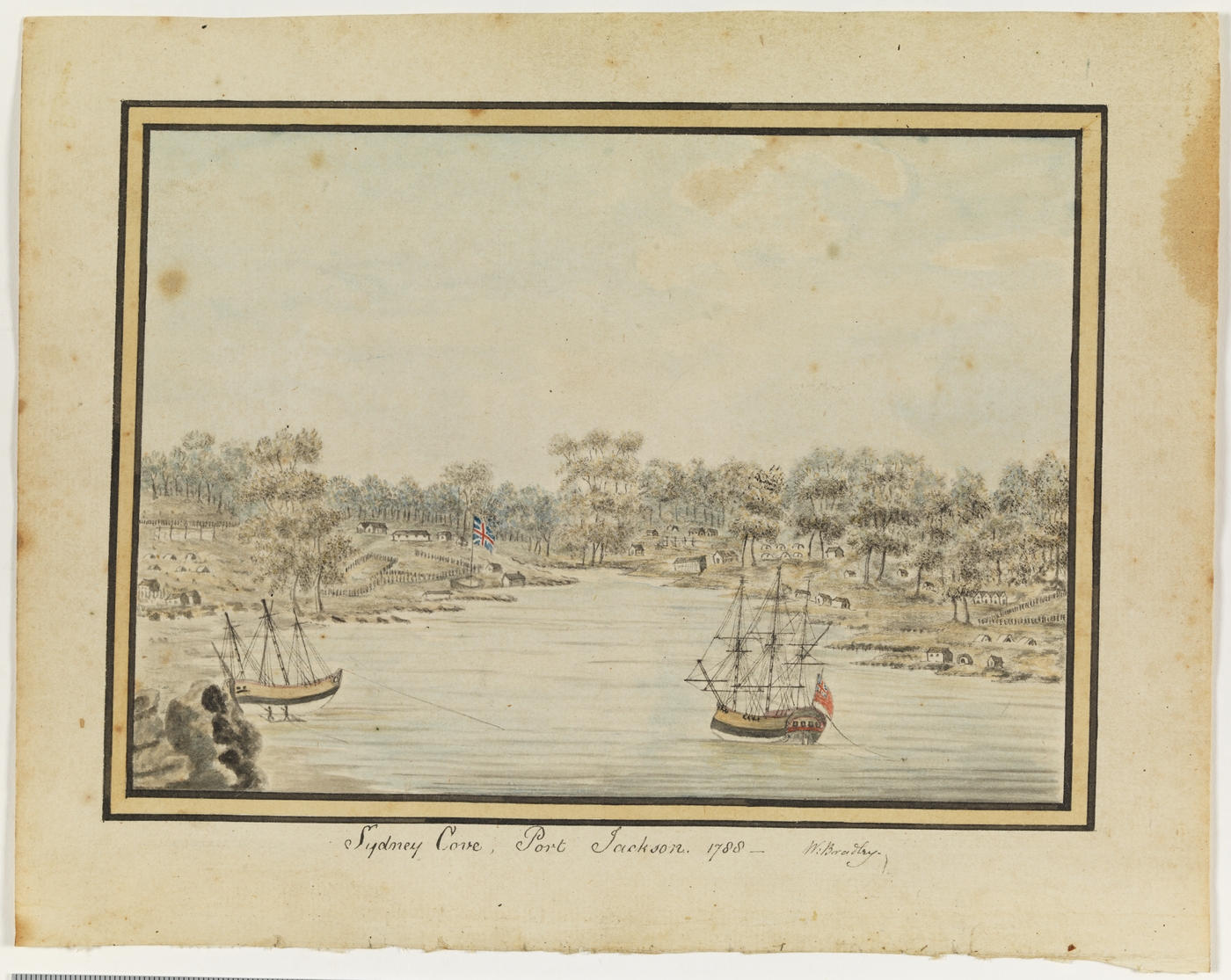

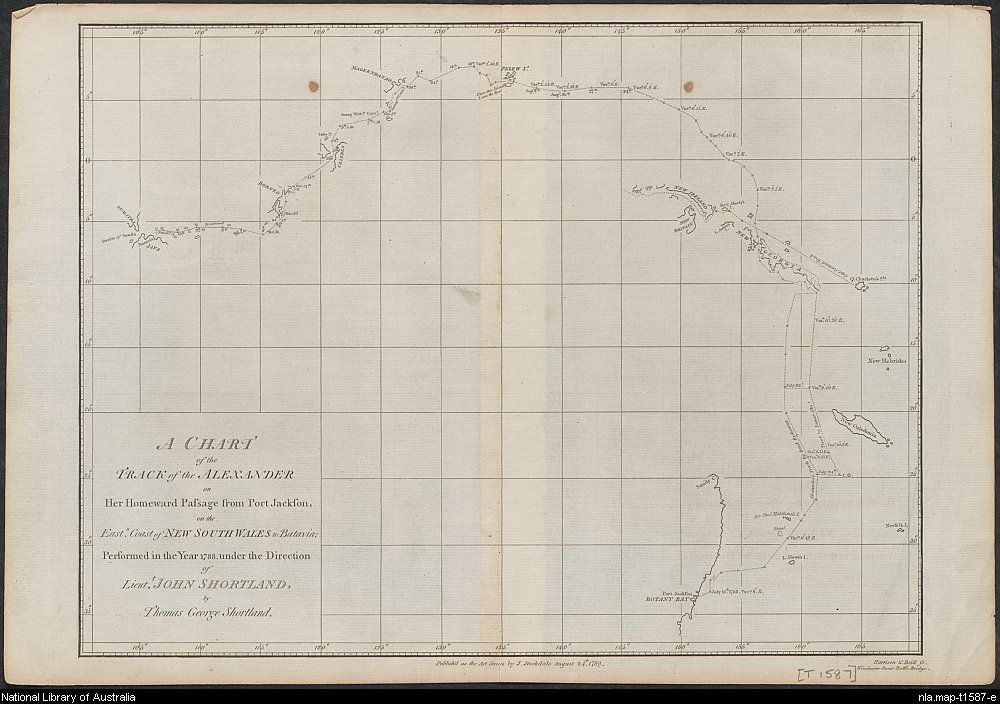

[media]During December the convoy battled severe storms and sustained damage and many on Alexander fell ill in the final dash to Botany Bay. The ship finally arrived on 19 January 1788 and Alexander's men were put to work ashore, cutting grass to feed their precious livestock. This work was interrupted, however, when the fleet were ordered to set sail again for more suitable land at Sydney Cove. The ship anchored in its final destination on 26 January, unloaded its prisoners and supplies and set sail for the return voyage within six months. On its return voyage, the ship lost 17 of its crew to scurvy as it approached the island of Borneo. [14] [media]After taking on board the crew of Friendship, also stricken with scurvy, the ship struggled to reach Batavia (Jakarta) as the crew were so sick only one man 'was able to go aloft'. [15] The ship arrived in England on 3 June 1789 and was chartered by the East India Company until the early 1800s before it disappeared from the Lloyd's Register in 1809.

References

Bradley, William. A Voyage to New South Wales. December 1786–May 1792. Mitchell Library. http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a138.html.

Chapman, Don. 1788: The People of the First Fleet. Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981.

Gillen, Mollie. The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet. Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1989.

Historical Records of New South Wales. Sydney: Charles Potter, Government Printer, 1892. Open Library. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL25518110M/Historical_records_of_New_South_Wales.

King, Jonathan. The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88. Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982.

White, John. Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales. London: J Debrett, 1790. Project Gutenberg Australia. http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0301531h.html.

Notes

[1] Quote from Ballad published in Whitehall Evening Post, London, 19 December 1786. See also Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32. Crew numbers in Mollie Gillen, The Founders of Australia: A Biographical Dictionary of the First Fleet (Sydney: Library of Australian History, 1989), 427

[2] 'Phillip's views on the conduct of the expedition and the treatment of convicts', 1787, 51, in Historical Records of New South Wales, 1892, available online at Open Library, https://openlibrary.org/books/OL25518110M/Historical_records_of_New_South_Wales, viewed 10 January 2015

[3] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32. Also in Don Chapman, 1788: The People of the First Fleet (Sydney: Cassell Australia, 1981), 64; Chris Cunneen and Mollie Gillen, 'John Black Caesar (1763–1796)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, 2005, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/caesar-john-black-12829, viewed 12 January 2015

[4] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 32. Also in William Bradley, 'Journal titled A Voyage to New South Wales', original ms in State Library of NSW, transcript available online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a138.html, 19 January 1787, viewed 12 January 2015

[5] William Bradley, Journal titled A Voyage to New South Wales, original ms in State Library of NSW, transcript available online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a138.html, viewed 12 January 2015

[6] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 16

[7] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 54

[8] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (London: J Debrett, 1790), available online at Project Gutenberg Australia, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0301531h.html, viewed 10 January 2015

[9] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (London: J Debrett, 1790), available online at Project Gutenberg Australia, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0301531h.html, viewed 10 January 2015

[10] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (London: J Debrett, 1790), available online at Project Gutenberg Australia, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks03/0301531h.html, viewed 10 January 2015. Also in Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88, (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 69

[11] Several accounts reference the incident including: William Bradley, Journal titled A Voyage to New South Wales, original ms in State Library of NSW, transcript available online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a138.html, viewed 12 January 2015; David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 1, 1798, Project Gutenberg Australia, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm, viewed 10 January 2015, Philip Gidley King, The Journal of Philip Gidley King, 1786–1790, original ms in State Library of NSW, transcript available online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a1519.html#a1519009, viewed 12 January 2015

[12] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 88

[13] Jonathan King, The First Fleet: The Convict Voyage That Founded Australia, 1787–88 (Melbourne: Macmillan, 1982), 98. Also in William Bradley, Journal titled A Voyage to New South Wales, original ms in State Library of NSW, transcript available online at http://acms.sl.nsw.gov.au/_transcript/2007/D00007/a138.html, viewed 12 January 2015

[14] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 1, 1798, Project Gutenberg Australia, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm, viewed 10 January 2015

[15] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, vol 1, 1798, Project Gutenberg Australia, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/12565/12565-h/12565-h.htm, viewed 10 January 2015