The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Hydro Majestic

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Hydro Majestic

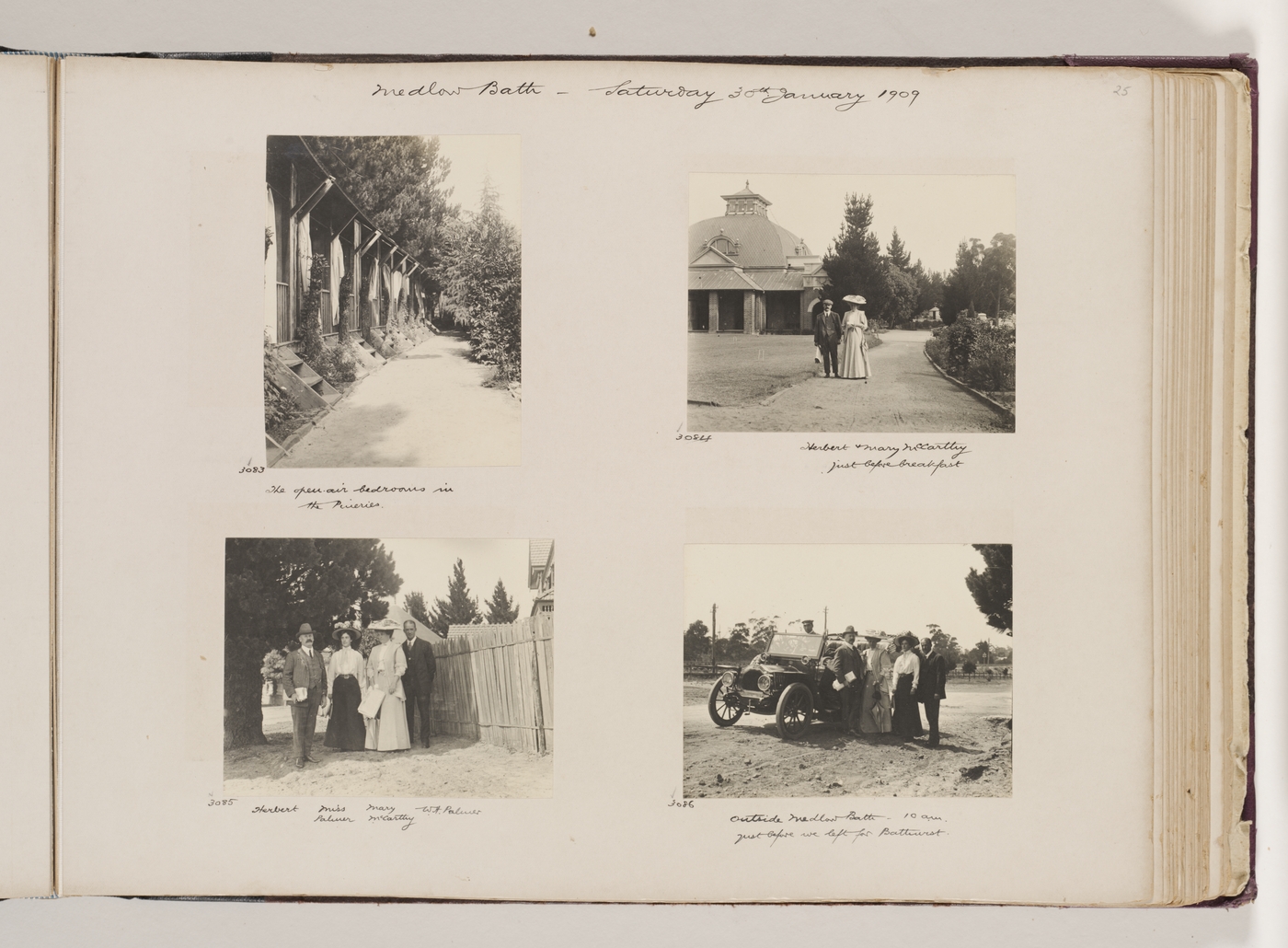

[media]As motorists head west through the small town of Medlow Bath, close to the highest point in the Blue Mountains, they encounter one of Australia's most unusual buildings. With its distinctive concert hall dome and eccentric jumble of architectural styles, the Hydro Majestic hotel snakes for over a kilometre along the escarpment overlooking the Megalong and Kanimbla valleys. Given its charismatic founder, generations of loyal guests and several reincarnations since its Edwardian 'golden age' origins, the hotel has acquired a nostalgic patina of celebrity and myth.

Health

This imposing edifice is the grand vision of wealthy entrepreneur Mark Foy. His successful drapery business, opened with brother Francis in Sydney in 1885 and named in honour of their late father, expanded into one of the city's best known department stores.

As a regular guest at European and British spas, particularly Smedley's Hydropathic Establishment in Derbyshire, Foy was inspired to take his share of the family retail business to establish Australia's first major health resort in the Blue Mountains.

Foy began buying land at his chosen site at Medlow in 1901. In late 1902, he wrote to Francis from London with detailed sketches and costings for construction and operation of a 50-room sanatorium closely modelled on Smedley's. He confided that the opinions of family and friends were 'that it will be a huge failure…I myself don't expect it to pay more than 10% on my outlay for 3 or 4 years but yet one never knows.' [1]

Though later often described as a 'folly', Foy's gamble was a highly expensive but calculated one. In the 1880s and 1890s, the upper Blue Mountains had emerged as a popular tourism destination for the leisured class with several well-appointed hotels, notably the Carrington in Katoomba, numerous guest houses and a reputation for the romance and charm of its nature walks and waterfalls [2] and the health benefits of its ozone-laden air. [3]

Foy's creation

The Medlow resort was in every respect Mark Foy's creation, reflecting his personality and preoccupations. Based on Foy's own concept sketches, [4] long galleries were built to connect three pre-existing buildings on the escarpment, the Belgravia hotel and two cottages, as well as Foy's striking domed concert and dance hall (called a casino), reportedly prefabricated and shipped from the USA.

In November 1903 NSW Railways added 'Bath' to the town's name at Foy's request. The Medlow Bath Hydropathic Establishment's much publicised opening on 4 July 1904 saw a party of VIPs motored to the mountains in a raging snowstorm. They were greeted by the sight of the resort lit up with electricity four days before the City of Sydney was connected to electric lighting. A rotating searchlight on the casino dome shone like a beacon. There are several versions of this origin story with details such as the casino's heating failing and the first guest booking in for a year. [5]

The Sydney Mail and NSW Advertiser published photos and applauded 'the outcome of a patriotic desire on the part of a successful business man …to supply New South Wales with an institution equal to any of the famous hydropathic establishments of Europe.' [6] National pride would remain the tone of the many journalistic tributes to Foy and his venture, amplifying the superlatives of Foy's own marketing. [7]

The unique self-contained resort boasted its own electricity plant, boiler and ice houses, sewerage plant, library, hotel shop, billiard room, grand dining room, art gallery and a telephone in every guest room connected to each other and the Sydney exchange. 'Surely this is the very excess of luxury to be able to conduct one's business affairs from one's own bedroom,' enthused the press. [8]

[media]Lavish decorations and artworks and the employment of a Chinese chef and Turkish waiters reflected globe-trotter Foy's taste for the exotic. The grounds included gardens, orchards, and lawn bowls, croquet and tennis courts. There were extensive walking tracks [9] for guests to enjoy the views and the bush while down in the valley was a shooting box, golf course and horse racing track.

Thanks to Foy's love of cars guests were motored on local tours including to Jenolan Caves. A clifftop flying fox brought daily produce up from Foy's valley farm. [10]

The state-of-the-art hydropathic clinic offered water-cures and other rigorous treatments for a wide range of ailments, overseen by Dr Baur, a German therapist hired from a leading Swiss spa. [11] Foy had predicted 'if he cannot make it a success coupled with my own expenditure then I am sure such a place is not wanted in Australia.' [12]

By 1906, Foy had accepted hydropathy's lack of appeal, not helped by the fact that the local spring had dried up and the spa water, imported in copper tanks from Baden-Baden, tasted dreadful. [13]

Wealth

A keen yachtsman, [14] Foy deftly changed tack. Rebranded as the Hydro Majestic, his exclusive luxury hotel was marketed from 1906 to the wealthy and fashionable for its opulence, fine food, entertainments and diverse recreational activities. In 'How I Saw The Bush' supposedly written by an unidentified British tourist, the hotel is extolled as 'Monte Carlo, whirled across twelve thousand miles of sea…with a slice of the Louvre and the Tuilleries (sic) thrown in.' [15]

Foy was adept at exploiting publicity. In 1908 Foy entertained officers and crew of the visiting US fleet and did so again in 1925. [16] The same year, the hotel hosted Canadian boxer Tommy Burns in preparation for the controversial 26 December heavy weight title match with Jack Johnson at the Sydney Stadium in Rushcutters Bay. [17]

[media]The hotel was renowned for its exuberant fancy dress balls, expressing Foy's own theatrical streak and quirky humour. He enjoyed dressing up – as Napoleon, for example, at a 'plain and fancy dress ball' in March 1908. [18] A 1909 photo shows Foy in his wife's ball gown and hat for the annual St Patrick's servants' ball and dinner where guests swapped places with hotel staff for the evening. [19]

Foy entertained members of his own social circle such as actor and later JC Williamson's managing director, Hugh Ward, and the hotel itself attracted its share of high society and celebrity guests. In 1915 the Rajah of Pudukkotai courted Melbourne socialite Molly Fink, the beginning of their scandalous inter-racial marriage. [20]

Australia's first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, died of heart failure while a guest in 1920. During his global lecture tour on Spiritualism in 1921, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle stayed with his family, praising Medlow Bath as a 'little earthly paradise' and the hotel as 'an Arabian Nights palace'. [21]

That same year film director Raymond Longford and his co-director Lottie Lyell shot scenes for their high society murder thriller The Blue Mountains Mystery at the Hydro Majestic and the Carrington. [22]

Other famous names have entered the trove of stories around the hotel. They include German armaments heiress Bertha Krupp who supposedly donated a grand piano and Dame Nellie Melba who performed in the casino. While these stories are difficult to substantiate from archival sources, they survive as legends of the hotel's glamorous past.

On Foy's travels abroad he collected crowd-pleasing curiosities, none more so than the 'Medlow Mermaid'. Advertised in the local paper in 1913, the seven foot long 'mermaid' and eight and half foot 'merman', reportedly purchased in Libya, could be viewed for the price of a shilling. [23]

Family

With plans to live abroad, Foy decided in 1913 to lease the Hydro Majestic to his commercial rival James Joynton-Smith, owner of the Carrington and Imperial hotels. For extended periods, Joynton-Smith closed the Hydro for maintenance and renovations. On 18 August 1922 a catastrophic fire broke out and destroyed the Belgravia hotel, the Belgravia Wing and the art gallery with its entire collection. [24]

Smith's lease was not renewed and Foy returned to rebuild and manage the hotel, reinventing it as a family resort for a less exclusive market. The tariff was cut to ₤2 12 s 6d a week and newspaper advertisements promised 'good plain and plenty eats…open for just Ordinary Folk, without the fad of dressing for dinner'. [25]

Post-war, the Blue Mountains became a favoured destination for honeymooners and the Hydro was no exception. [26] The Depression saw working class families offered cheap rail fares and wealthier families sell or close up their homes in Sydney and take up residence at the hotel. [27]

On 2 January 1932 the Hydro hosted a beauty parade and competition in front of a reported audience of 3,000. [28] In its new guise, the hotel was changed too. Cinema décor artist, Arnold Zimmerman, redecorated the casino in art deco style in 1925 and again with dramatic hunting scene paintings in 1935 while the new streamlined Belgravia Wing and Bellvue (sic) Lounge Bar [29] opened in the late 1930s. Foy floated the family-owned hotel as a public company in 1936 but kept control over its management.

War and peace

During World War II, the Hydro fulfilled its patriotic duty, requisitioned as a base for the US Army's 118th General Hospital. With a formal handover ceremony on 19 July 1942, Foy and his nephew and hotel manager, 'Bud' Macken, arranged a staff photo with a placard 'Closed for the Duration'. [30]

The American doctor in charge of the hospital conversion recalled extensive work needed on 'a nice middle class rather dowdy, rundown hotel'. He refuted later claims by Foy's grand-daughter (and family historian), Mary Shaw, of acts of vandalism by bored patients such as shooting out light bulbs and killing prize goats. [31] The Hydro was handed back in February, 1943 and reopened six months later.

With its characteristic informal humour, the Hydro's special Victory Pacific dinner menu on 16th August, 1945 started with 'Curtin Soup (threw everything in)'. [32] Peace meant business as usual. Naturalist 'Mel' Ward, son of Foy's friend Hugh Ward, opened his idiosyncratic natural history museum (including some 25,000 crabs) on the hotel grounds in 1943 and drew big crowds.

Compensated by the Australian government for the American occupation, Foy undertook a last major addition to the hotel before his death in November, 1950.

Defying the general post-war decline of Blue Mountains tourism, the Hydro Majestic remained an attractive destination, updating its décor and amenities to suit changing tastes. In 1956 Cinesound recorded a well-attended negligee and swimsuit fashion parade around the hotel's swimming pool. [33]

The 'grand old lady'

By the 1970s, however, despite the loyalty of generations of guests, particularly honeymooners celebrating their anniversaries, the Hydro Majestic struggled with maintenance costs and declining occupancy rates and profits.

In 1984 the hotel was sold to Sydney barrister John North who undertook major renovations. Marketing metaphors of 'a total facelift' for a 'grand old lady' echoed the hotel's long association with feminine beauty. [34] That same year, the NSW State Heritage Register recognised 'her' unique status and features.

In late 1996 the hotel changed hands again and its new owners, the Mah family, declared their intention 'to make the Hydro Majestic what it was before.' [35] Marketing material referred to 'an Edwardian folly with a touch of Art Deco' now 'restored…to its former glory': [36] the romantic allure of the hotel's past had become a key ingredient for its commercial future.

In 1997, the Hydro, 'as turreted and turbaned as an elephant house' and 'a vast Brighton dance hall on a pier pillared with rock' [37] became a memorable backdrop for Delia Falconer's acclaimed poetic novel The Service of Clouds set in Katoomba between 1907 and 1922.

The property was managed by hotel companies Peppers (1998-99) and later Accor (2001-2006) with further renovations and refurbishments by each of the owners. In December 2002, the hotel attracted widespread media attention, narrowly surviving a fierce onslaught by bushfire though still faced with declining occupancy.

The 'grand old lady' was sold to the Escarpment Group in 2008 and closed for a $30 million redevelopment designed to include a dedicated history display. [38] The revitalised hotel opened for business in October 2014, the latest incarnation of Mark Foy's inspired vision.

Further reading

Silvey, Gwen. Happy Days: Blue Mountains Guest Houses Remembered. Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1996.

Low, John. Pictorial Memories: Blue Mountains. Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, imprint of Atrand, 1991.

Prince, Perri. The Jewel of the Mountains. Documentary (47 mins), narrated by Lorraine Bayly. Turning Point Films, broadcast Foxtel History Channel, 4 July 2015.

Notes

[1] Letter from Mark to Francis Foy, 14 November, 1902, Paul Innes collection, copied with permission from grand-daughter Mary Shaw's Foy collection

[2] Julia Horne, The Pursuit of Wonder: How Australia's Landscape was Explored, Nature Discovered and Tourism Unleashed (Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 2005), 100–139

[3] John Low, Pictorial Memories: Blue Mountains (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, imprint of Atrand, 1991), 36–43 and 74–76

[4] Letter from Mark to Francis Foy, 14 November, 1902 and letter from Mark Foy to Mr Richardson 17 December 1902, Paul Innes collection, copied from Mary Shaw's Foy collection

[5] 'Social Items', Sunday Times, 10 July 1904; see also Mary Shaw, interviewed by Maryanne Quinn, Speaking of The Past Oral History program, 19 September 1984, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[6] Sydney Mail and NSW Advertiser, 20 July 1904

[7] 'Australia's Foremost Holiday Resort' in Trips around Sydney, New South Wales, NSW Government Tourist Bureau, Sydney, 1909, 52

[8] The Mountaineer, 24 June 1904

[9] Foy employed Murdo McLennan to construct an additional five kilometres of tracks to the existing 18 kms in the area, Jim Smith, 'Hydro Majestic Hotel Walking Tracks', Locality 10, no 2 (1999): 13–17

[10] Gwen Silvey, Happy Days: Blue Mountains Guest Houses Remembered (Crows Nest, NSW: Kingsclear Books, 1996), 42–43

[11] Indication of Medlow Bath Hydropathic Establishment handbook, 1904, in Hydro Majestic files, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[12] Letter Mark Foy to Mr Flaig, 15 January, 1903, Paul Innes collection, copied from Mary Shaw's Foy collection

[13] Mary Shaw, interviewed by Maryanne Quinn, 19 September 1984, Speaking of The Past Oral History program, Local Studies, Blue Mountains City Library

[14] GP Walsh, 'Foy, Mark (1865–1950)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/foy-mark-6367, viewed 20 November 2015

[15] 'How I Saw the Bush: By a British Globe-Trotter', The Bulletin Poster Press, 19, 6. Available online at State Library of Victoria, http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/82015, viewed 23 November, 2015

[16] The Evening News, 25 August 1908, 9,

[17] The Argus, 2 November 1908, 8

[18] Queensland Figaro, 26 March 1908

[19] 'Staff Ball, Hydro Majestic', Local Studies Image Library, Blue Mountains City Library File: 000\000830

[20] Edward Duyker and Coralie Younger, 'Fink, Esme Mary Sorrett (Molly) (1894–1967)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/fink-esme-mary-sorrett-molly-10182, viewed 23 November, 2015

[21] Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Wanderings of a Spiritualist (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1921), 255

[22] Macken, Bud and Macken, Estelle: interviewed by Graham Shirley: Oral History, 20 February 1979, National Film and Sound Archives, Title No: 376529; The Blue Mountains Mystery: Documentation: Lottie Lyell and Raymond Longford (centre) directing a scene, Marjorie Osborne (Mrs Tracey), Arthur Higgins (cameraman), 1921, National Film and Sound Archive, Title No: 357882

[23] The Blue Mountain Echo, 15 August 1913

[24] The Blue Mountain Echo, 18 August 1922, 5

[25] The Record of the Blue Mountains, 1 February, 1924, 50; tariff also shown in Hydro Majestic:Medlow Bath: Blue Mountains advertisement, 1923, National Film and Sound Archives, Title No: 1248695

[26] John Low, Pictorial Memories: Blue Mountains (Alexandria, NSW: Kingsclear Books, imprint of Atrand, 1991), 52

[27] Mary Shaw, interviewed by Maryanne Quinn, Speaking of The Past Oral History program, 19 September 1984, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[28] Clipping from The World Pictorial, 4 January, 1932, in Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[29] Blue Mountains Daily, 24 March, 1939, 2

[30] Paul Innes collection, copy in Hydro Majestic Hotel files, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[31] Dr F Tremaine Billings Jnr quoted in Brian Madden, Hernia Bay: Sydney's Wartime Hospitals at Riverwood (Canterbury, NSW: Canterbury District Historical Society, 2001) 37; Mary Shaw, interviewed by Maryanne Quinn, Speaking of The Past Oral History program, 19 September 1984, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[32] Paul Innes collection

[33] Negligees and Swimsuits: Fashion Show In the Great Outdoor’, Cinesound newsreel, 1956, National Film and Sound Archives, Title No: 84673

[34] Marketing brochure, c1987 in Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[35] The Blue Mountains Gazette, 23 October 1996

[36] Marketing brochure, c1994, Local Studies collection, Blue Mountains City Library

[37] Delia Falconer, The Service of Clouds (Australia: Pan Macmillan, 1997), 101

[38] Video interview with interior designer Peter Reeves, 'Grand design to restore icon to its Majestic heyday,' Sydney Morning Herald, 15 June 2013, http://www.smh.com.au/nsw/grand-design-to-restore-icon-to-its-majestic-heyday-20130614-2o98j.html viewed on 19 November 2015

.