The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Lesbians

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Lesbians

Desire [media]and sexual encounters between women have been an integral aspect of life in Sydney for centuries. At times female homosexual activity has been an acknowledged form of sexual expression, while at others it has been the subject of intense social disapproval and taboo. Social attitudes toward, and understandings of, lesbian identity have also shifted over time, with eighteenth- and nineteenth-century religious notions of lesbianism giving way to medical models in the twentieth century and both being challenged by lesbian and gay political activists from the 1970s onwards.

[media]Although lesbianism has become an increased subject of public discussion in recent decades, a lack of social concern for women's experiences and widespread hostility toward lesbianism has meant that prior to the 1970s, few written sources relating to the subject exist. This absence of sources has inevitably shaped the picture we can construct of female same-sex desire in the past. Nevertheless, a number of detailed studies have been undertaken into lesbian history in Australia, including Lucy Chesser's work on cross-dressing and sexuality at the turn of the century and Ruth Ford's work on lesbian identity in the early twentieth century. [1] However, while a growing body of historical literature has explored Australian lesbian experience in the past, much of this work has taken a broadly national view and few local studies exist. [2]

This article considers the specificities of the local context and the ways in which the experience of lesbians in Sydney differed from those in rural New South Wales or other Australian cities.

Singing love magic songs

It is likely that sexual relationships between Aboriginal women constituted recognised forms of sexual behaviour which were included in ritual activities prior to European settlement. However, very few accounts of same-sex activity between women exist from this period and it is therefore extremely difficult to draw any firm conclusions for the Sydney region. Those accounts that are available in written form were produced by Europeans after settlement and can therefore only offer a limited and potentially inaccurate picture of female homosexual activity in Australia before 1788. German-born missionary, Carl Strehlow, who headed the Finke River Mission at Hermannsburg in Central Australia, between 1894 and 1922, provided the following account of sexual activity between Aboriginal women:

The unnatural vice of the women, woiatakerama (carried out using a little stick bound with string, called iminta, by two women, one of whom performs the role of the man), is practised by the eastern and western Aranda [and] occurs also among the western Loritja, the Yumu and Waiangara in the west, and among the Katitja, Ilpara, Warramunga etcs., who live north of the McDonnell Ranges. The Loritja call this vice: nambia pungani. [3]

Accounts drawn from the writings of white, male observers, such as Strehlow, are inevitably overlaid with European notions of same-sex activity as 'unnatural' and a 'vice' and such evidence is further problematised by the fact that European men would have enjoyed limited opportunities to record activities occurring in women's spaces. Nevertheless, an ilpindja or love magic song in which women show their labia to each other, was reported by Geza Roheim, an anthropologist working in Central Australia in the late 1920s, suggesting that Aboriginal oral literature may also have referred to female same-sex activity. [4]

Gendered customs practised within Aboriginal communities also point to a history of women's camps and sacred spaces in which women elders could live together away from the settlement and engage in women-centred activities. The concentrations of gendered essences or powers within these sites are dangerous to men without the appropriate protection and men therefore avoid the area. For women, these sites may have offered the space to build intimate relationships with each other over many centuries. [5]

Lesbianism and illicit sexuality amongst convict women

Sexual activity between women became an increased focus of social anxiety in the years after European settlement. Throughout the nineteenth century, religious notions of sexual activity between women as sinful and immoral dominated social attitudes towards the subject. Official records indicate that concerns regarding the behaviour and morality of convict women frequently centred on issues of sexual morality.

Female factories – [media]such as the one established at Parramatta in 1804 – quickly acquired a reputation as centres of moral disorder and contagion. As places in which large numbers of convict women were collected in one location, with freedom of movement and activity after completing their day's work, female factories were thought to act as breeding grounds for female vices, such as smoking, swearing and illicit sexual activity. [6] Lesbianism was believed to be widespread amongst female factory inmates and an Inquiry into Female Convict Prison Discipline in 1841 noted a recent case of two women who had been 'detected in the very act of exciting each others passions – on the Lord's Day in the house of God – and at the very time divine service was performing.' [7]

Dr WJ Irvine, superintendent of the Ross Female Depot in Tasmania, provided a detailed account of same-sex activity amongst female convicts in correspondence sent to the Comptroller-General of Convicts during the 1850s. Offering an analysis of homosexual behaviour, based on his own observation and the evidence of female inmates, Irvine argued that two types of women engaged in this activity: the 'pseudo-male' or 'man-woman' and the feminine woman who was attracted to the masculine type. He suggested that the feminine women were often amongst the youngest female convicts and noted:

These young girls are in the habit of decorating themselves scrupulously, & making themselves as attractive as they can, before resorting to the 'man-woman', if I may so style her, on whom they have bestowed their affections. [8]

Sexual activity of this kind between women, he argued, formed a central part of the structure and hierarchy of the subculture in female factories and was therefore also likely to be occurring in the Parramatta factory in this period.

Cultural attitudes to lesbianism in the early twentieth century

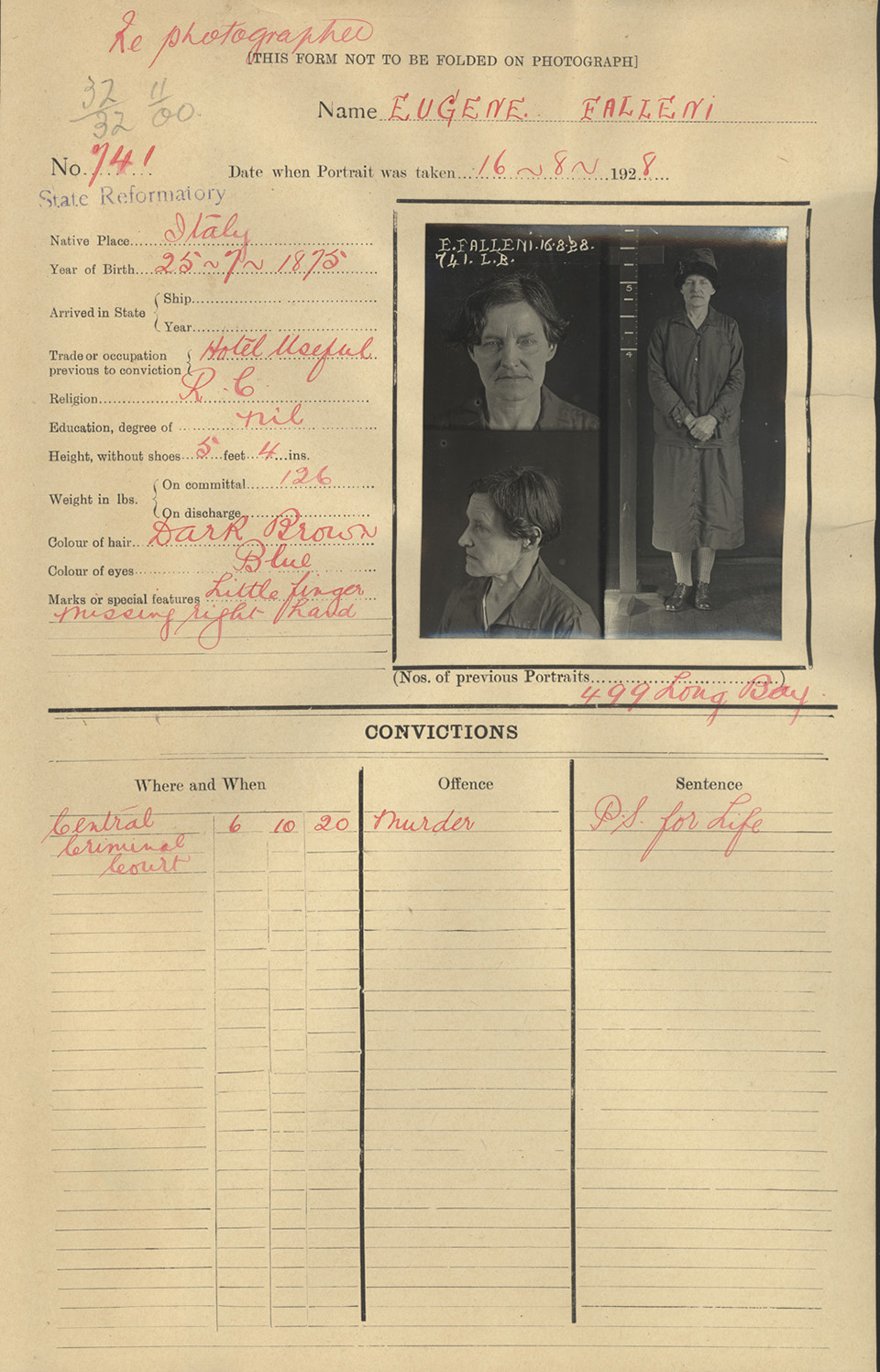

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, public discussion of lesbianism in Australia was sporadic and largely confined to the tabloid press. Sensationalist newspapers occasionally reported scandals involving female same-sex desire, such as the case of the 'man-woman', Eugenia Falleni, which emerged into the public arena in 1920.

[media]Such cases were reported from across Australia, although it is likely that urban environments such as Sydney may have offered greater anonymity, enabling women to successfully pass as a man. A working-class Italian migrant, Falleni had been living in Drummoyne for some years as a man, Harry Crawford, and had been twice married, firstly to Annie Birkett and subsequently to Lizzie Allison. In 1920, when Annie Birkett's son, Harry, reported that his mother had been missing since 1917, the police determined that an unidentified female body found in the bush near Chatswood three years' earlier was that of Annie Birkett. Upon visiting Harry Crawford to interview him about his first wife's disappearance and presumed death, police were informed that Crawford was in fact a woman. The discovery of a dildo amongst Crawford's possessions confirmed the police in their suspicion that Falleni was an untrustworthy character and she was subsequently charged with murder.

Press coverage of the investigation and trial is illuminating of contemporary notions of cross-dressing and female same-sex desire. Much of the press discussion of the case focused on the issue of Falleni's masquerade and an article in the Truth newspaper was couched in such a way as to suggest that the charges Falleni was facing concerned her cross-dressing and marriages rather than the murder. [9] Concepts of homosexuality, although becoming available in Australia at this time, were not applied to Falleni in this case and she was presented instead as a monstrous figure, a 'man-woman' or hermaphrodite, whose cross-dressing was evidence of her deceitful character. [10]

During and after World War I, however, the emergence of the new scientific field of sexology was beginning to have an impact on Australian attitudes to lesbianism and medical discourses became increasingly influential in defining concepts of female same-sex desire. European and Australian sexologists had begun a process of categorising a range of sexual behaviours and identifying typical characteristics belonging to those individuals who practised them in the late nineteenth century.

The work of British sexologist, Havelock Ellis, who lived in Sydney and New South Wales between 1875 and 1879, was important in developing the concept of sexual inversion, which linked same-sex desire in women to masculine character traits and physical appearance. Ellis argued that sexual inversion in women and men was 'congenital' or inborn and these ideas were beginning to impact on wider social ideas about lesbianism in the 1920s. [11]

By the 1930s, however, the notion of sexual inversion was losing ground to the new psychoanalytic theories of sexual behaviour proposed by Sigmund Freud. Freud argued that all humans possessed bisexual potential at birth and underwent a process of sexual development during childhood and adolescence. This developmental journey, he suggested, led most adults from bisexuality to homosexuality and ultimately to heterosexuality, but in a number of unusual cases, sexual development could become arrested at an earlier stage, causing the individual to remain attracted to members of their own sex. Sydney psychiatrist, John McGeorge, applied psychoanalytic theories in his consideration of homosexuality amongst female hysterics in 1932 and by the 1950s, psychoanalytic explanations of homosexuality had come to dominate social attitudes to lesbianism in Sydney and across Australia. [12]

Unlike sexual activity between men, lesbianism was never directly penalised under Australian law. Nevertheless, lesbians in Sydney were subject to disapproval and occasional harassment from the police, using licensing laws and a range of other available legislation.

Sergeant Lillian Armfield, a detective with the New South Wales Police Force between 1915 and 1949, declared that 'the authorities should try to do something to stamp out the growing cult of lesbianism,' which was 'a menace too serious to be ignored just because it is such an ugly and unpleasant issue to drag out into the open.' [13] One figure who caused particular difficulties for Armfield and her colleagues in 1920s Darlinghurst was female gangster, Iris Webber, who became involved in two separate shooting affrays after she 'lured away a criminal's girlfriend to live with her.' [14]

In the mid-twentieth century, bars frequented by homosexual men and women were occasionally raided by police and as late as the 1970s, a lesbian couple were arrested in a Sydney park after police found one of the women lying with her head in the other woman's lap. [15]

Lesbian social networks

In response to this widespread social disapproval, many women hid their desire for other women, fearing the loss of employment or ostracism by family and friends. Identifying potential partners or lesbian friends was extremely difficult in the absence of public discussion of lesbianism, although the larger population and infrastructure provided by the urban environment in Sydney offered women greater opportunities than in rural areas. Oral history evidence suggests that many women did meet other lesbians at work or in social groups such as dance or sports clubs. [16]

Lesbian socialising in the mid-twentieth century largely focused on private friendship networks and women entertained friends at private house parties on weekends and public holidays. [17] From the 1960s onwards, however, a commercial bar scene began to develop in Kings Cross and elsewhere, catering to a 'camp' or homosexual clientele. Lesbians frequented the Chez Ivy wine bar on Oxford Street, which opened from Monday to Saturday until 10 o'clock at night. When Chez Ivy closed for the evening, women could continue their night at the Purple Onion drag club on Anzac Parade. [18] The camp scene in this period constituted a secretive and closed community, but by the 1970s, a larger number of venues across Sydney were drawing a lesbian clientele.

The Native Rose pub, near the University of Sydney, attracted lesbian students and feminists to hear women's bands, such as the Stray Dags, perform and the Sussex Hotel on Sussex Street also hosted a women's night. [19] Perhaps the most popular lesbian bar of this period was Dawn O'Donnell's Ruby Red's on Crown Street. Described by a regular as 'good fun' and 'fairly dykey', Ruby Red's was frequently crowded after ten o'clock at night, with women buying drinks from the bar and others on the dance floor:

It was disco in the early part of the disco era and the changing colours in the dance floor and the strobe lighting and the mirror balls and all of those sort of things, which now are retro and they laugh at them, but it was fun. [20]

Lesbian and gay social groups also began to form in Sydney in the 1960s and 1970s. Both men and women were members of the Chameleons and Pollynesians social clubs in the 1960s and, from 1972 onwards, Clover Businesswomen's Club in Drummoyne organised dinners, sporting events and other social activities for lesbians. [21] The development of these social spaces and networks enabled women to forge new models of lesbian identity such as butch/femme and to collectively resist the negative attitudes toward lesbianism prevailing in society.

Political awakening

The 1970s witnessed the emergence of lesbian political organisations in cities across Australia, which began to challenge longstanding religious and medical constructions of homosexuality. Sydney provided much of the impetus for this activism and, on 10 September 1970, the mixed lesbian and gay organisation, Campaign Against Moral Persecution Incorporated (CAMP Inc), was founded in North Sydney by John Ware and Christabel Poll. The group intended to form a body of informed people who could put the homosexual viewpoint across publicly and Poll argued:

as far as the wider society is concerned, we should concentrate on providing information, removing prejudice, ignorance and fear, stressing the ordinariness of homosexuality and generally reassuring and disarming those with hostile attitudes. Concerning homosexuals, we think a policy of development of confidence and lessening of feelings of isolation and guilt, where they exist, is vital. [22]

The first public meeting was held on 6 February 1971 in a church hall in Balmain and by the end of 1971, branches had been formed in capital cities and university campuses across Australia. CAMP New South Wales acted as an umbrella group with subgroups on law reform, married gays, religion and social activities doing most of the active political work. The organisation was reformist rather than revolutionary and was criticised by groups such as Sydney Gay Liberation as '"insular", "reformist", "conservative" [and] "bourgeois".' [23] Nevertheless CAMP New South Wales held a number of public demonstrations and its founders encouraged members to 'come out' and publicly acknowledge their sexuality as a political strategy in challenging social attitudes. [24]

Despite the role of a woman in co-founding the group, tensions emerged relatively quickly over the place of women in CAMP New South Wales. Some women members felt that the group prioritised political issues which were of primary importance to men, such as law reform, and an attempt to establish a separate women's meeting within CAMP failed amid opposition from some male members. [25] The apparently sexist attitudes of some men in the organisation caused further tension and a CAMP member, Margaret Jones, felt that

they treated the women very badly and saw us as being their coffee-makers, to clean up the clubrooms after their drunken parties and they were ... patronising and of course they were misogynist. [26]

In April 1972, Margaret called a meeting in her home to discuss the formation of a separate women's group, and the Camp Women's Association (CWA) was formed. Although ongoing tensions existed over the role of women in CAMP New South Wales, individual women continued to work within the group and to hold 'women's coffee evenings' throughout the 1970s. By the late 1970s, the group was moving away from political campaigning toward a support function and in 1981 changed its name to The Gay Counselling Service of New South Wales.

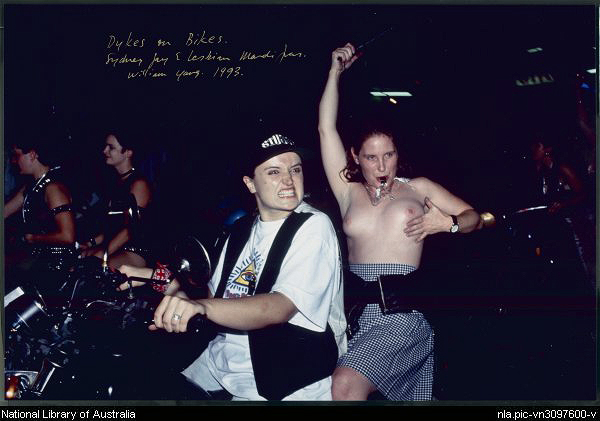

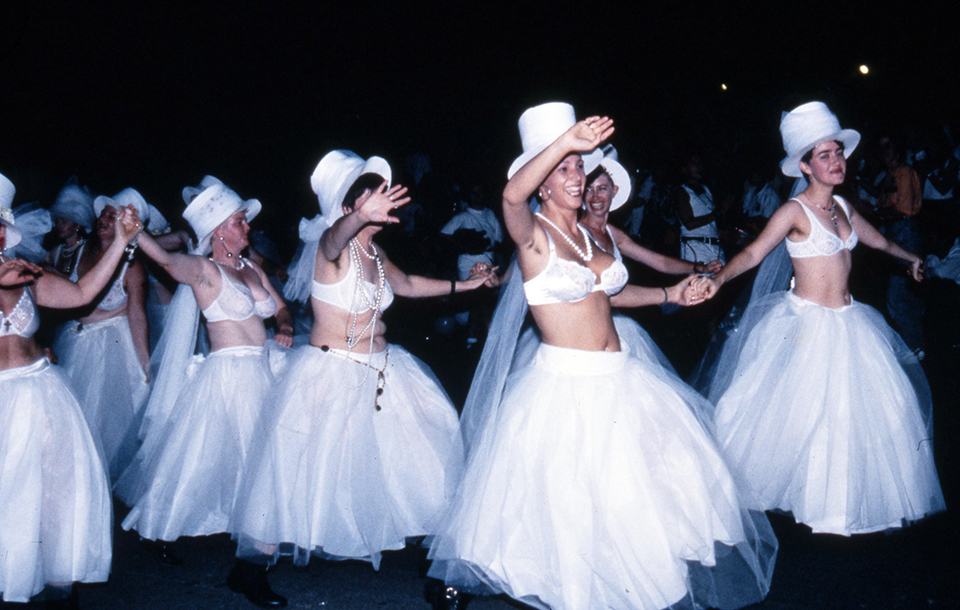

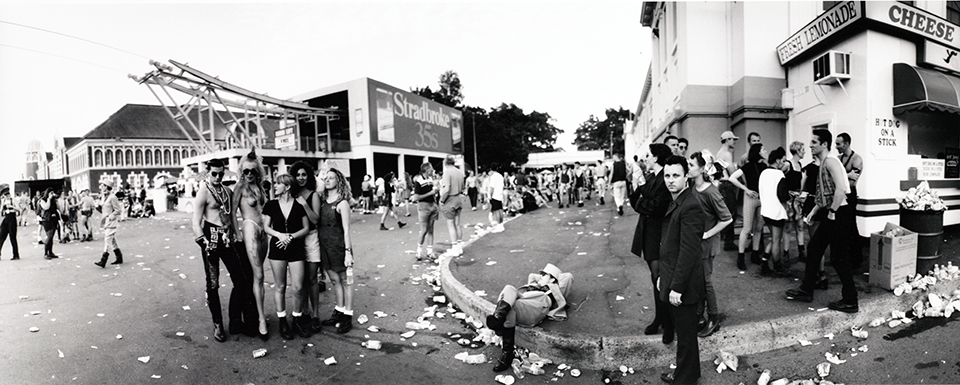

[media]The first Sydney Mardi Gras, held on 24 June 1978, was also a joint action involving lesbians and gay men. Originally intended as a street party to encourage non-political lesbians and gay men out of the bars and onto the streets, the night-time event ended in confrontation with the police and a number of arrests. A second Mardi Gras was held the following June to mark the continuing battle against police persecution and the Mardi Gras soon became a regular event. In 1981 Mardi Gras was moved to the summer and continues to represent an important international statement of lesbian and gay culture and politics in Sydney. [27]

Women's Liberation

Women's Liberation provided an alternative forum in which many Sydney women explored their sexuality in the 1970s and 80s, independently of gay men. Although some members of the women's movement were initially reluctant to embrace lesbian issues in the early 1970s, fearing that public awareness of lesbianism in the movement would discredit the broader political message of women's rights, lesbians nevertheless had a strong presence in Women's Liberation from the outset.

[media]Sydney lesbians were actively involved in the establishment and running of Sydney Rape Crisis Centre and Elsie Women's Refuge and participated in a wide range of political campaigns and demonstrations, often marching under banners which read 'Lesbians are Lovely.' Consciousness-raising groups at Women's Liberation House on Alberta Street, and elsewhere across Sydney, offered some women a space in which to explore their sexuality and a lesbian consciousness-raising group was formed in 1976. [28]

Many lesbians entered a vibrant social scene through feminism, socialising at women's dances and living in collective houses such as 'Canterbury Castle' and 'Crystal Street.' [29] As lesbians gained a more influential voice in Australian feminism in the mid-1970s, the phenomenon of political lesbianism emerged, with some women arguing that lesbianism represented a feminist political statement of withdrawing emotional and sexual energies from men. Some lesbians embraced a separatist way of life, living and socialising only with women, and a small number moved out of the city to found women-only communities on women's lands in rural areas of New South Wales. [30]

Lesbian culture

The 1970s and 1980s witnessed a boom in lesbian culture, with a range of novels, television programmes and films representing sexual desire between women. Australia's first lesbian novel, All That False Instruction, by Sydney lesbian Kerryn Higgs, was published in 1975 under the pseudonym Elizabeth Riley. In February 1979, the highly popular television series, Prisoner, went to air on Channel Ten and ran for a further eight years. Set in 'Wentworth' women's prison, the series was modelled on the experiences of female prisoners in Sydney's Mulawa and Melbourne's Fairlea prisons, and included a lesbian character, Frankie.

Lesbian magazines began to be produced by and for lesbians in the 1980s, with the national quarterly, Lesbian Network, appearing in 1984 and the Sydney-based national monthly magazine, Lesbians on the Loose, bringing out its first issue in December 1989. [media]These publications provided an invaluable source of information on the lesbian scene and community, in addition to providing a forum in which lesbian issues could be debated.

A number of lesbian short films and documentaries have been made in the decades since the 1970s and, in May 2001, Samantha Lang's Sydney-based lesbian thriller, The Monkey's Mask, was released, adapting Dorothy Porter's poetic story of the same name. Novels have also provided influential representations of lesbian identity and Claire McNab's Detective Inspector Carole Ashton novels have contributed to the lesbian crime genre against a Sydney backdrop.

New lesbian voices

The 1980s and 1990s witnessed increased recognition of the diversity of lesbian identities in Sydney and a range of new voices were heard within the lesbian communities. Debates about lesbian sexuality became increasingly heated and in 1984, Sexually Outrageous Women (SOW), a lesbian sex radical group, was formed in Sydney which challenged lesbian feminist notions of female sexuality. The production of Australia's first lesbian sex magazine, Wicked Women, in 1988 led to the development of a lesbian sexual underground in Sydney in the 1990s, centred on dance parties and SM and bondage performances. [31]

[media]At the same time, many lesbians were working alongside gay men in support and educational programs aimed at addressing the AIDS crisis. The question of exactly who should be included within the identity category 'lesbian' was also widely debated in the 1990s. In 1994, the Lesbian Space Project, a community project aimed at purchasing a building in Sydney in order to establish a 'lesbian space,' became mired in a bitter dispute about whether lesbian-identified transsexuals constituted 'lesbians' and should be entitled to use the space. [32]

Aboriginal lesbians have been increasingly vocal in the 1990s in challenging Anglo-Australian notions of lesbian identity and reshaping attitudes toward the relationship between race and sexuality. [33] [media]Meanwhile, political lobbying for lesbian and gay rights has continued and begun to have an impact in gaining greater legal recognition of lesbians. The Gay and Lesbian Rights Lobby has been campaigning since 1988 on a range of lesbian issues, including same-sex partnership legislation and gay and lesbian parenting rights. In June 2008 the New South Wales Parliament passed the Miscellaneous Acts Amendment (Same Sex Relationships) Act 2008, providing equal parenting rights to co-mothers of children born through donor insemination. Lobbying for same-sex partnerships legislation is ongoing at both the state and federal levels.

Sydney lesbians have been at the centre of much of the political activism and cultural production which has developed in Australia since the 1970s. The city's large population has historically provided sufficient anonymity for individual women to express or act upon a lesbian identity and, more recently, has afforded a vibrant lesbian community from which a social and political scene could develop. Nevertheless, Sydney's lesbians have also been affected by the moral and medical approaches which have shaped broader national attitudes, so that the experiences of Sydney lesbians have been both unique and typical of the wider Australian experience.

References

Lucy Chesser, Parting with my sex: Cross-dressing, inversion and sexuality in Australian cultural life, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2008

Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997

Pride History Group, Out and About: Sydney's lesbian social scene, 1960s–80s, Pride History Group, Sydney, 2009

Denise Thompson, Flaws in the Social Fabric: Homosexuals and society in Sydney, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985

Graham Carbery, A History of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, ALGA, Melbourne, 1995

Graham Willett, Living Out Loud: A history of gay and lesbian activism in Australia, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards New South Wales, 2000

Notes

[1] Lucy Chesser, Parting with my sex: Cross-dressing, inversion and sexuality in Australian cultural life, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2008; Ruth Ford, 'Contested Desires: Narratives of Passionate Friends, Married Masqueraders and Lesbian Love in Australia, 1918–1945', unpublished PhD thesis, La Trobe University, 2000; Ruth Ford, 'Disciplined, Punished and Resisting Bodies: Lesbian Women and the Australian Armed Services, 1950s–60s', Lilith 9, 1996; Ruth Ford, 'Lady-Friends and Deviationists: Lesbians and the Law in Australia 1920s–1950s', in Diane Kirkby (ed), Sex, Power and Justice: Historical Perspectives on the Law in Australia, 1788–1990, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1995, pp 33–49; Ruth Ford, 'Lesbians and Loose Women: Female Sexuality and the Women's Services During World War II,' in Joy Damousi and Marilyn Lake (eds), Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1995, pp 81–104; Ruth Ford, 'Speculating on Scrapbooks, Sex and Desire: Issues in Lesbian History', Australian Historical Studies 106, 1996, pp 111–26; Ruth Ford, '"The Man-Woman Murderer": Sex Fraud, Sexual Inversion and the Unmentionable "Article" in 1920s Australia', Gender and History vol 12, no 1, 2000, pp 158–96

[2] Garry Wotherspoon, City of the Plain: History of a Gay Sub-Culture, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991 describes the gay subculture in Sydney, but focuses entirely on gay men. Also predominantly male-focussed is Clive Moore, Sunshine and Rainbows: The Development of Gay and Lesbian Culture in Queensland, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia Qld, 2001

[3] Carl Strehlow, Die Aranda- und Loritja-Stamme in Zentral-Australien, Frankfurt a/M, 1907–1920, vol IV, part 1, p 98, cited in Gays and Lesbians Aboriginal Alliance, 'Peopling the Empty Mirror: The Prospects for Lesbian and Gay Aboriginal History,' in Robert Aldrich (ed), Gay Perspectives II. More Essays in Australian Gay Culture, Department of Economic History, University of Sydney, 1994, p 40

[4] Geza Roheim, Children of the Desert: The Western Tribes of Central Australia, New York, 1974, pp 183–4, cited in Gays and Lesbians Aboriginal Alliance, 'Peopling the Empty Mirror: The Prospects for Lesbian and Gay Aboriginal History,' in Robert Aldrich (ed), Gay Perspectives II. More Essays in Australian Gay Culture, Department of Economic History, University of Sydney, 1994, p 42

[5] Zohl de Ishtar, Holding Yawulyu: White Culture and Black Women's Law, Spinifex Press, North Melbourne, 2005, pp 30–33

[6] Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997; Kay Daniels, Convict Women, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards, New South Wales, 1998

[7] Joy Damousi, Depraved and Disorderly: Female Convicts, Sexuality and Gender in Colonial Australia, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997, pp 69–70

[8] WJ Irvine to Comptroller-General, Tasmanian Papers, no 107, f.13859, FM4/8515, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library

[9] Truth, 11 July 1920, p 9

[10] Ruth Ford, '"The Man-Woman Murderer": Sex Fraud, Sexual Inversion and the Unmentionable "Article" in 1920s Australia', Gender and History, vol 12 no 1, 2000, pp 158–96. There were a number of other cases involving cross-dressed women in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Australia: see Lucy Chesser, 'A woman who married three wives': Management of disruptive knowledge in the 1879 Australian case of Edward De Lacy Evans,' Journal of Women's History, vol 9 no 4, January 1998, pp 53-77; Lucy Chesser, '"When two loving hearts beat as one": Same-sex marriage, subjectivity and self-representation in the Australian case of Marion-Bill-Edwards, 1906–1916', Women's History Review, vol 17, no 5, 2008, pp 721–742; Lucy Chesser, Parting with my sex: Cross-dressing, inversion and sexuality in Australian cultural life, Sydney University Press, Sydney, 2008

[11] KJ Cable, 'Ellis, Henry Havelock (1859-1939)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 4, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972, pp 137–38; Havelock Ellis, Sexual Inversion, vol 2, Studies in the Psychology of Sex, FA Davis Company, Philadelphia, 1901. See also Sydney doctor, Robert V Storer, A Survey of Sexual Life in Adolescence and Marriage, Science Publishing Co, Melbourne, 1932

[12] JA McGeorge, 'Environment and Hysteria', Medical Journal of Australia, 26 November 1932, pp 656–58; Joy Damousi, Freud in the Antipodes: A cultural history of psychoanalysis in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 2005

[13] Lillian Armfield quoted in Vince Kelly, Rugged Angel: The Amazing Career of Policewoman Lillian Armfield, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, pp 80, 82

[14] Vince Kelly, Rugged Angel: The Amazing Career of Policewoman Lillian Armfield, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1961, p 78

[15] Melbourne Women's Liberation Newsletter, December 1978, p 8

[16] Interview with Margaret Jones, 12 September 2007; Interview with Virginia Binning and Ruth Ritchie by Sandra Mackay and Rebecca Jennings, 7 April 2007, Pride History Group Collection; Interview with Diana Nelson, 23 April 2008

[17] Interview with Beverley and Georgina, 22 December 2008; Interview with Margaret Jones by Michelle Holden, 10 November 2003, Leichhardt Local Library, Local History Collection; Interview with Margaret Jones, 12 September 2007; Jon Rose, At the Cross, Andre Deutsch, London, 1961, pp 16–17. See also, L, "We Were All Terrified in Those Days", in 'Filling Some Gaps: Lesbian History Excerpts from the "Hunter Pride" Exhibition', compiled by Lyndall Coan, in Jim Wafer, Erica Southgate and Lyndall Coan (eds), Out in the Valley: Hunter gay and lesbian histories, Newcastle Region Library, Newcastle New South Wales, 2000, p 205; Con Anemogiannis, The Hidden History of Homosexual Australia, Special Broadcasting Service Corporation, 2005

[18] Interview with Ivy Richter by John Witte, 22 May 2006, Pride History Group Collection; Carolyn Bloye, Unpublished talk given at launch of Pride History Group, Out and About: Sydney's lesbian social scene, 1960s–80s, Pride History Group, Sydney, 2009, 28 February 2009. See also Pride History Group, Camp Nites: Sydney's emerging drag scene in the '60s, Pride History Group, Sydney, 2006, pp 11–15, 17

[19] Interview with Robyn Plaister, 20 December 2007

[20] Interview with Diana Nelson, 23 April 2008

[21] Interview with Jan McInnies and Margaret Cummins by Sandra Mackay and Rebecca Jennings, Pride History Group Collection; 'A History of Clover', Clover Businesswomen's Club, 1987, Pride History Group Collection. See also Pride History Group, Camp as a Row of Tents: The life and times of Sydney's camp social clubs, The Pride History Group, Sydney, 2007, pp 18–21, 23

[22] Christabel Poll, 'Gay Liberation', The Old Mole 7, Sydney University, 26 October 1970, p 5

[23] Denise Thompson, Flaws in the Social Fabric: Homosexuals and society in Sydney, George Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1985, p 10

[24] Camp Ink, vol 2, no 2/3, December 1971/ January 1972

[25] 'CAMP women's association newsletters', Folder 25, Gays Counselling Service of New South Wales Papers, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, MSS 5836; See also Sue Wills, 'Inside the CWA – The Other One', Journal of Australian Lesbian Feminist Studies 4, June 1994, pp 6–22

[26] Interview with Margaret Jones, 18 September 2007

[27] See Pride History Group, New Day Dawning: The early years of Sydney's gay and lesbian Mardi Gras, Pride History Group, Sydney, 2008; Graham Carbery, A History of the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras, ALGA, Melbourne, 1995; Graham Willett, Living Out Loud: A history of gay and lesbian activism in Australia, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards New South Wales, 2000, pp 138–39

[28] Interview with Sandra Mackay, 2 July 2007; Interview with Robyn Plaister, 20 December 2007

[29] 'A Radicalesbian Lifestyle', Refractory Girl Lesbian Issue, Summer 1974, pp 12–15

[30] Judith Ion, 'Degrees of separation: lesbian separatist communities in northern New South Wales, 1974–95', in Jill Julius Matthews (ed), Sex in Public: Australian Sexual Cultures, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards New South Wales, 1997, pp 97–113

[31] Kimberley O'Sullivan, 'Dangerous desire: lesbianism as sex or politics', in Jill Julius Matthews (ed), Sex in Public: Australian Sexual Cultures, Allen and Unwin, St Leonards New South Wales, 1997, pp 120–23

[32] Affrica Taylor, 'Lesbian space: more than one imagined territory', in Rosa Ainley (ed), New Frontiers of Space, Bodies and Gender, Routledge, London, 1998, pp 129–41

[33] Abby Duruz, 'Sister Outsider, or "Just Another Thing I Am": Intersections of Cultural and Sexual Identities in Australia', in Peter A Jackson and Gerard Sullivan (eds), Multicultural Queer: Australian Narratives, Harrington Park Press, Binghampton, New York, 1999, pp 169–82

.