The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Milsons Point

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Milsons Point

[media]Prior to the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, the waterways of the harbour linked north and south Sydney. Row boats and ferries crossed the harbour as a way of life, forever establishing the lower shores of North Sydney as a major transport hub.

The original inhabitants of these foreshores, rocky cliffs and points were known as the Cammeraygal. Their land covered most of the lower north shore and included the area of Milsons Point and Kirribilli. As early as the 1790s, soon after European settlement in Port Jackson, large land grants displaced the Cammeraygal, as did the land granted to James Milson for whom Milsons Point is named. Watkin Tench rightly observed 'that the Cammeraygal possessed the best fishing grounds in Port Jackson.' [1] Perhaps this accounts for its Aboriginal name, for the Cammeraygals knew this land as Kiarabilli or Kiarabilly, believed to translate into English as 'a good fishing spot.' [2]

[media]Milsons Point and Kirribilli form part of the bay and peninsula on the lower edge of North Sydney, located under the northern approaches of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Milsons Point is to the bridge's west and Kirribilli to its east. The point is located in North Sydney Council boundaries and, prior to 1890, it was within the boundaries of the Borough of East St Leonards.

Early landholders

James Milson senior arrived in Sydney in 1806. Although he was long associated with the Milsons Point area, it was not until Governor Thomas Brisbane's term of office (1821–25) that Milson was officially granted his 50 acres (20 hectares). This land was originally part of a larger grant given to Robert Ryan in 1800, and a subsequent ownership takeover by Robert Campbell, a prominent Sydney merchant and landholder.

The colony's growth saw the expansion of white settlement beyond the southern shores of Sydney Cove. James Milson made good use of his north shore land and skillfully utilised its best advantages: fresh water supplies and ballast for the shipping trade which dominated the waterways of Port Jackson. According to one contemporary observer,

Mr Milson, North Shore, has cut a cistern in the solid rock capable of containing 100 tons of water [which is] supplied from an excellent spring constructed so as to fill, by means of a leather hose conductor, ship's boats along the beach where the water is of sufficient depth to float a ship of the line. [3]

When Milson first arrived in Sydney he took up a position as a labourer on Kilpack's farm in the Castle Hill area. It was this experience which enabled him to work his rocky and unyielding land, to produce a variety of foods to sell to passing ships, as well as grazing cattle to furnish the township with milk. In 1826 a bushfire engulfed the whole of the north shore and Milson's land, his first home, Brisbane Cottage, and the Milk House were destroyed. Afterwards, Milson built two larger, more substantial homes further up the point. Brisbane House was a stone house with two storeys facing Lavender Bay, then commonly called Hulk Bay, after the convict hulks moored nearby. Grantham was a large bungalow-style sandstone home on a larger plot of land (now occupied by the Greenway Housing Commission flats). Both homes were demolished in 1925–26 to make way for the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Water supply

The location of Milsons Point ensured that it would play a significant role in the development of the lower north shore. Its proximity to the city meant it was the spot for the connection of the first water supply to the northern shores. This supply was piped from the closest southern point, Dawes Point, to Milsons Point in 1885. Before this, landowners and residents had to rely on springs, creeks and wells for their watering needs. Regular complaints about the quality of the water, combined with the establishment of the Metropolitan Water Sewerage and Drainage Board in 1888, resulted in a link from the Ryde pipeline in 1892 to the rapidly growing north shore. As population and demand increased, pipelines were extended well into the early twentieth century.

Ferries

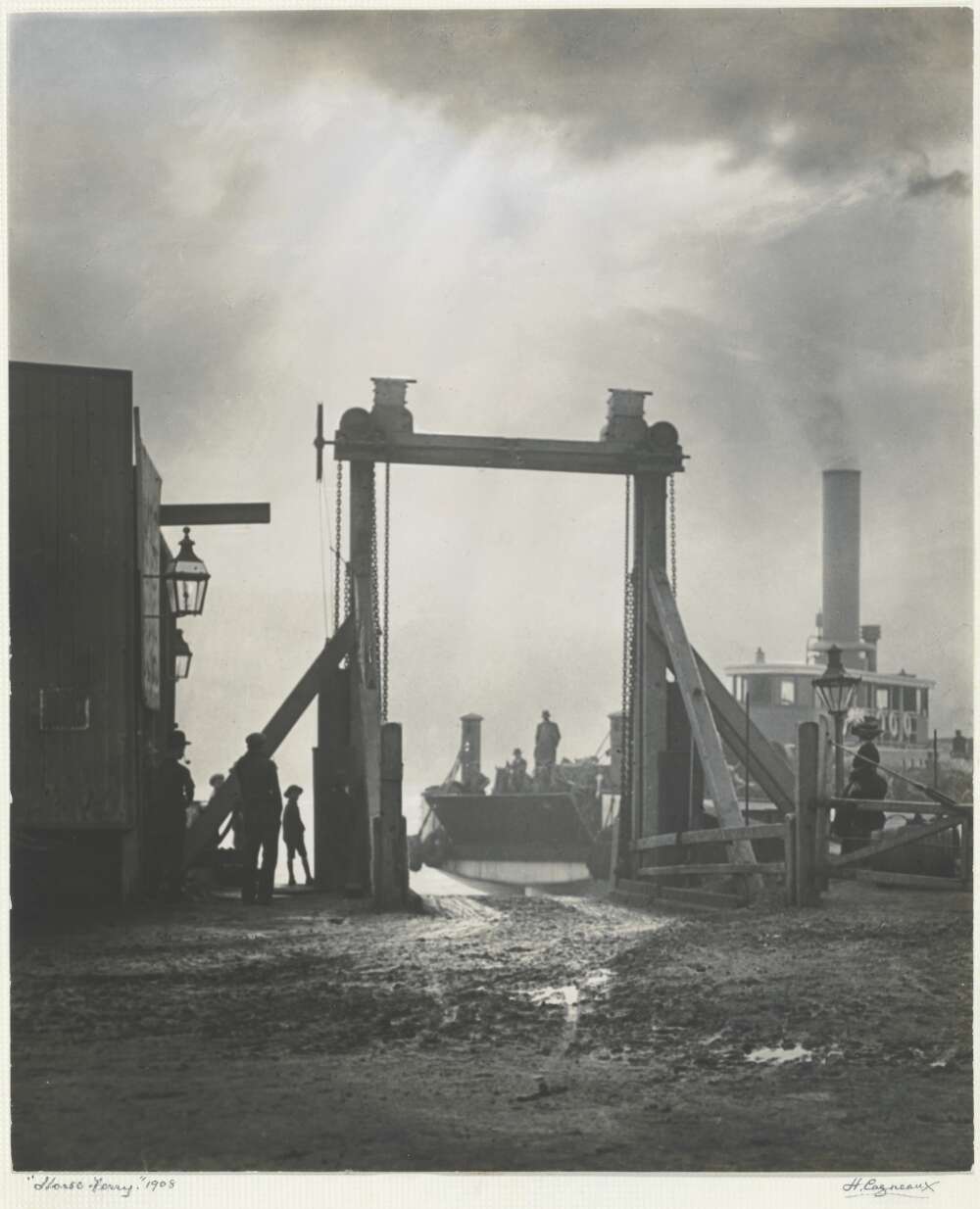

media]Water dominated the daily life of the lower north shore, and the dependency on water travel to and from the city sparked the development of the ferry trade. By the end of 1929 it was carrying over 40 million passengers per annum. This peak dramatically fell to a third by the time of the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, due to the scaling down of ferry services by Sydney Ferries Ltd. [4]

[media][The first ferry services had been offered by opportunistic resident settlers such as William (Billy) Blue, one of the first of the watermen who plied their trade from the north side of the harbour. Formalised and regular services were later introduced from McMahons and Blues Point, the peninsula immediately to the west of Milsons Point. Services increased dramatically between the 1830s and the1860s and included a vehicular ferry to carry horses and carts, as well as people across Port Jackson for business, shopping and pleasure. In the early 1860s, James Milson junior and several of his business colleagues banded together to form the North Shore Ferry Company, later known as Sydney Ferries Ltd. The ferry they introduced ran between Circular Quay and Milsons Point, and was licensed to carry 60 passengers.

[media]In 1886, cable trams began their run from the Milsons Point ferry terminus up to Ridge Street, North Sydney via Miller Street. This cemented Milsons Point as the transport hub for all of the lower north shore. To coincide with the cable tram, a ferry arcade was constructed as an interchange between trams and ferries. In 1893 the extension of the railway link to Milsons Point delivered even more passengers to this terminus. A stylish and notable structure, the Milsons Point Ferry Arcade dominated the landscape until its demolition in 1924 to make way for bridge works. In May 1887, the North Shore and Manly Times had described it as,

Consisting principally of two waiting rooms and decorated throughout in a highly satisfactory manner, the new structure will be surmounted by a domed tower having walls of 48 feet high and a total elevation over all of 64 feet … each room will be fully provided with all necessary conveniences whilst the dome itself, to be surmounted by a flagstaff, will serve as an excellent look-out … Leaving the waiting room and walking up the main street the pedestrian will pass beneath a very extensive arcade. [5]

The effect of the Bridge

The first railway station had opened in 1893 when the Hornsby to St Leonards line was extended through Wollstonecraft and Waverton, around Lavender Bay to Milsons Point. It was moved to a new site north of this in 1915, and then again in 1924, when the bridge work began and the site was acquired for the construction workshops of Dorman Long Co. To ensure ease of movement and transfer between the modal changes, the vehicular ferry service was moved east away from the construction works to a new wharf at Jeffrey Street, Kirribilli. The Milsons Point passenger terminal was moved back to its original position in Lavender Bay, and a modern innovation, the escalator, was installed to move people up and down the cliff face between the shores of the bay and Alfred Street. These new people-movers were designed to move 10,000 people per hour, and caused quite a stir amongst the first to ride them. According to the resident Victor Wills, the area at this time,

was densely populated… there were many terraced houses and they were two storey. They lined Alfred Street from Dind's Street where Dind's Hotel was where they had all the bohemian gatherings … I used to go down to Milsons Point to meet [my sister] when she came back from work … there were shops from the Milsons Point wharf right up till Fitzroy Street, a wide variety of shops, fish shops and cooked shops – what we would now call take away food shops – used to call them cooked shops in those days … there were so many houses cleared out of there. [6]

Hardship was a way of life for many local residents in the 1920s. The building of the bridge gave some people hope and employment, but others lost their homes and their livelihood without compensation and with nowhere to go. The Milsons Point Ferry Arcade, a local landmark and meeting place, soon disappeared, together with many shops, churches, terrace houses, workers' cottages, local businesses and hotels. The old colonial landmark homes, such as those once belonging to the Milson family and other gentry who had settled in the area, also disappeared.

The bridge opened up a new railway station on the western side of its northern approach, and ferries still operated to and from the local wharves, although with a much reduced level of service. Yet rebuilding the area did not proceed quickly. Decisions by the state and local governments had to be reached to allocate the land for private or public use. The area immediately under the new bridge was dedicated as a park and named in honour of the government engineer, JJC Bradfield. The foreshore land of the disused workshops and wharves became the subject of much debate for town planners, councillors and local members of parliament.

Luna Park

An approach from Luna Park in Glenelg to shift their amusement park from South Australia to the shores of Lavender Bay and onto the site of the Dorman Long workshops proved successful, and a lease was granted. Luna Park opened on 4 October 1935 to much fanfare and excitement. The park was a place of reprieve and a focal point for entertainment when World War II broke out in September 1939. It continued to attract visitors over the years, when it was properly maintained and run by experienced showmen, such as David Atkins and Harold Phillips. Ted Hopkins was a key figure in the construction of the park on the harbour foreshores and its main operator from 1935–70. Afterwards the amusement park was run by businessmen and neglect set in. A tragic fire in one of its major attractions, the Ghost Train, in 1979, resulted in its closure. Resuscitation by redevelopment and restoration occurred between the 1980s and 2000s, causing the park to open and close until its recent reopening in 2004.

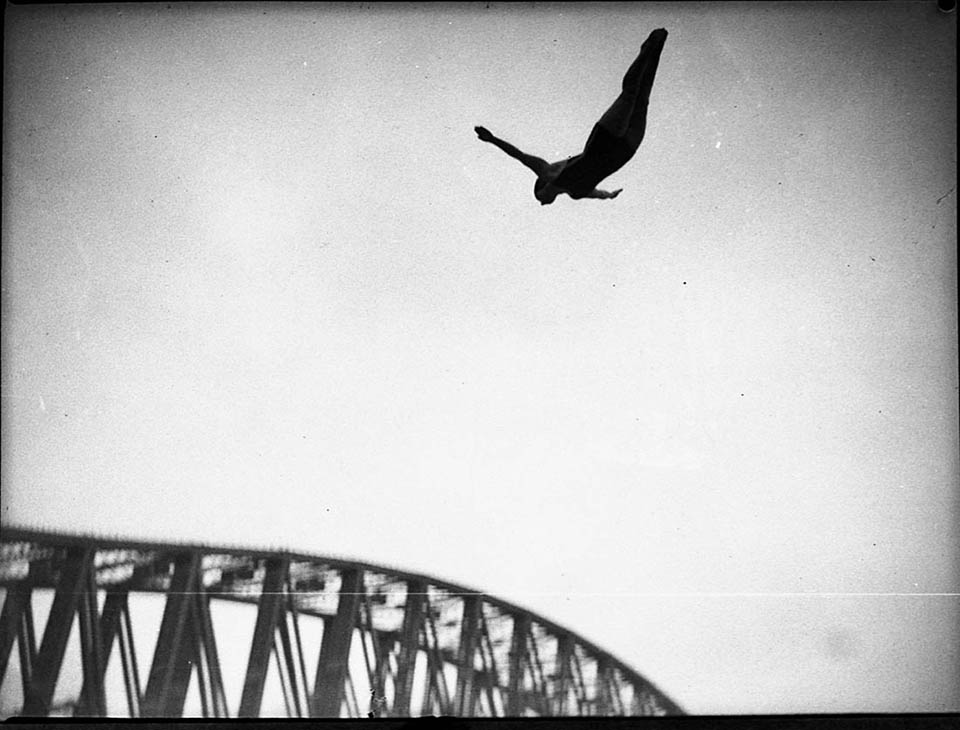

North Sydney Olympic Pool

The Dorman Long workshops also provided space for a large and safe harbourside pool at North Sydney. The North Sydney Olympic Pool opened its doors on 4 April 1936, emblazoned with art deco designs and brickwork. Its modern water filtration system provided a healthier swimming environment and it was nicknamed 'the wonder pool'. When Sydney hosted the 1938 Empire Games, the Milsons Point pool, already an established fixture for swimming competitions and even used as a film set, was the [media]stage for the Games' swimming and diving programs. As its use increased and changed from the 1930s to the 1980s the pool acquired a bubble cover to ensure its place as a year-round attraction. While Luna Park remained in private leasehold, the pool's operation was controlled by the local council. An additional heated pool and refurbishment, negating the need for the bubble cover during the winter, was added in 2000. These landmarks have ensured that Milsons Point remains a popular northside location.

A new skyline

The building boom of the second half of the twentieth century dramatically altered the Point's views and vistas. High-rise buildings replaced the low-scale housing which had dominated the point throughout the first half of the century. Developers grabbed opportunities to bundle sites together and demolish the old for the new. This was permitted prior to any substantial heritage conservation legislation or local environment plans. The redevelopment of the remaining western side of Alfred Street with its vantage points over the harbour escalated unchecked and the landscape irrevocably changed.

To gain a glimpse into the past of the point, visit the northern end of Bradfield Park adjacent to Milsons Point Station. Here, the local council has erected interpretive signage noting the buildings which once lined the eastern side of Alfred Street.

References

Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2003

Mackay Godden, North Sydney Heritage Study Review, North Sydney Council, North Sydney, 1993

Lianne Hall, Down the Bay: the Changing Foreshores of North Sydney, North Sydney Council, North Sydney, 1997

Michael Jones, North Sydney 1788–1988, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1988

Joan Lawrence, Lavender Bay to the Spit, Kingsclear Books, Sydney, 1999

Margaret Park, Naming North Sydney, 2nd edition, North Sydney Council, 1996

Margaret Park, Designs on a Landscape: A Planning History of North Sydney, Halstead Press, 2003

Eric Russell, The Opposite Shore: North Sydney and Its People, John Ferguson with North Shore Historical Society and North Sydney Council, 1990

Catherine Warne, Pictorial History: Lower North Shore, Kingsclear Books, Sydney, 2005

Notes

[1] Ian Hoskins, Aboriginal North Sydney: An Outline of Indigenous History, North Sydney, North Sydney Council, 2007, p13

[2] Val Attenbrow, Sydney's Aboriginal Past, University of New South Wales Press, Kensington, 2003, p 9; Margaret Park, Naming North Sydney, 2nd edition, North Sydney Council, 1996, p 74

[3] Scott Milson, The Earth Brought Forth: the Milsons of Milsons Point, 4SQ publishing, Bondi Beach, 2006, p 33

[4] Len A Clarke, North of the Harbour: a Brief History of Transport to and on the North Shore, Newey and Beath, Sydney, 1976, p 27

[5] North Shore and Manly Times, May 1887 in David Earle, Local Studies Collection, North Sydney Heritage Centre

[6] Victor Wills quoted in Margaret Park, Building a Bridge for Sydney: the North Sydney Connection, North Sydney Council, North Sydney, 2000, p 13

.