The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

North Sydney

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

North Sydney

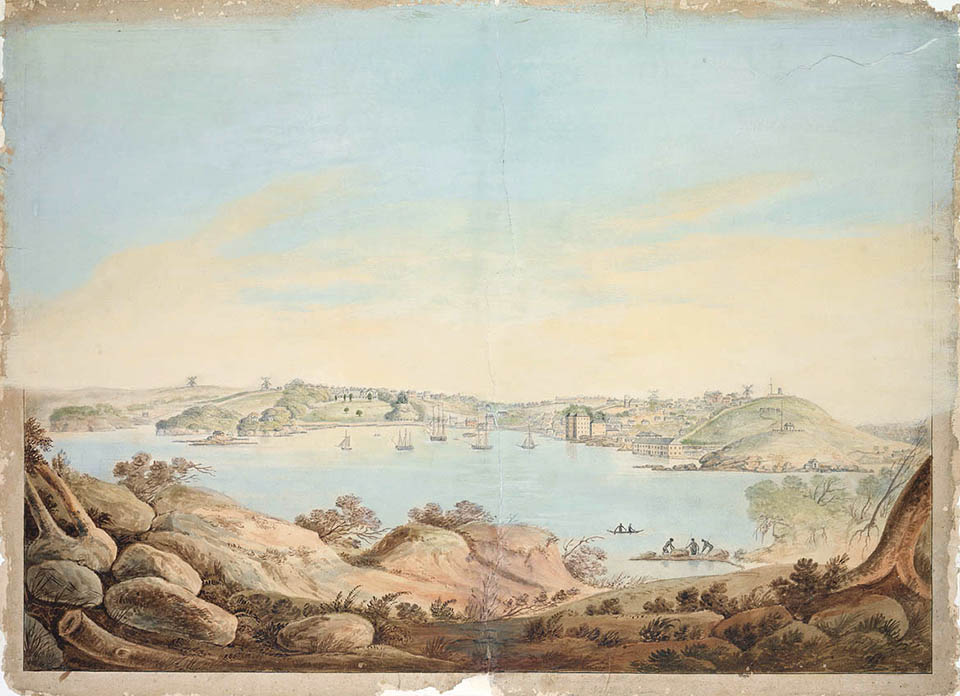

[media][media]North Sydney is on the traditional land of the Cammeraygal people. It is a mostly landlocked suburb located in the North Sydney local government area, bounded to the east by the Warringah Expressway, to the south by the suburb of Lavender Bay, on the south-east by Kirribilli and Milsons Point, and the suburbs of Crows Nest, Waverton and Cammeray share boundaries to the north and west. The suburb also extends to the harbour at Neutral Bay, inclusive of the High Street promontory. The North Sydney central business district, a major feature of the suburb, is one of Australia's largest commercial centres, serving both the local population and the Sydney region. Landmark buildings in the suburb include the Independent Theatre, the Don Bank Museum, Stanton Library, and prestigious schools such as Monte Sant' Angelo Mercy College, Sydney Church of England Grammar School (Shore) and Wenona.

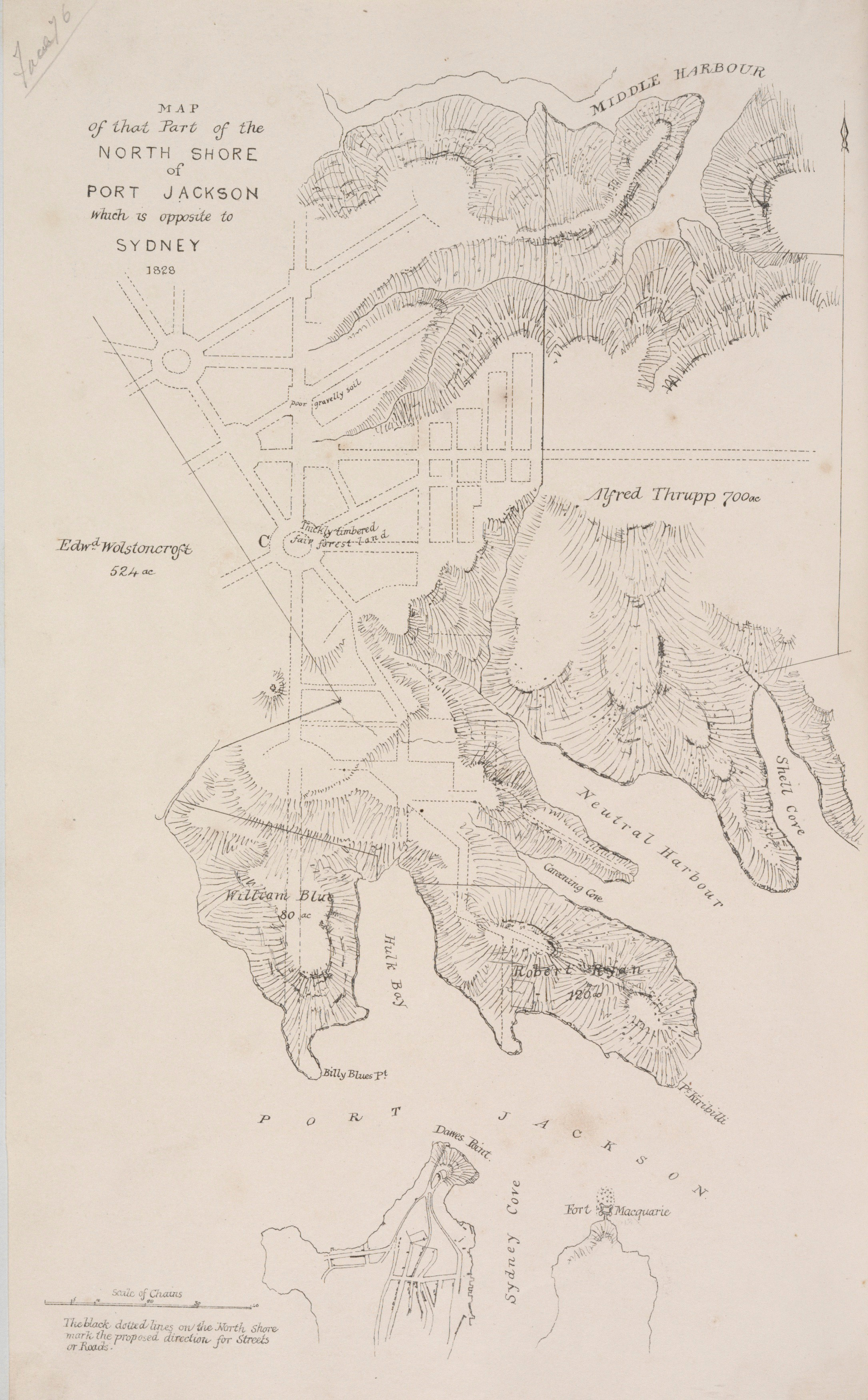

Early surveys

[media]As early as 1828, Sir Thomas Mitchell had been asked to provide a report on James Milson's claim for land on the north shore, after a fire destroyed deeds to his property. In preparing this report, Mitchell also identified an eligible site for a Township, land which to this point had not yet been disposed of in various land grants. The recommendations included in Mitchell's 1828 plan included suggestions for streets and subdivisions, a reserve and a great road towards the north of the colony and Broken Bay.

Mitchell's plan was discarded, and in 1836 the entire area was resurveyed in response to demands of several petitioners to purchase land in the area. By 1838 the basic road structure of the town centre was established on a traditional 10-chain grid, with Berry, Mount, Blue and Lavender streets running east-west and Miller and Walker streets running north-south. This initial site for the Township (nowadays the commercial centre of North Sydney) was a small rectangle of Crown land north of Hulk Bay (later named Lavender Bay). It was the southern tip of a reserve for the extension of Sydney. Initially, in 1838 48 half-acre building allotments in three sections were offered for purchase by application.

Naming the town

The Township of St Leonards was formally gazetted in 1838. It is thought to have been named after St Leonards (near Hastings in Britain) by Major Mitchell when he surveyed the district in 1828. An alternative, though less probable explanation, is that the district was named for the British statesman, Thomas Townshend, Baron Sydney of Chislehurst, whose name was given to Sydney Cove by Governor Phillip in 1788, and who was created Viscount Sydney of St Leonards on his retirement from politics in 1789.

However the name St Leonards was arrived at, the present name of North Sydney was adopted by the alderman of the newly consolidated borough in 1890. Although there was a strong sentiment attached to the name St Leonards, Alderman Clark proposed the name North Sydney, arguing that it would give the new borough more prestige if they wanted to borrow more money. At this vote, North Sydney won the day. [1]

Subdivision and development

After 1843 there were occasional sales of Crown lots, with substantial sales, especially to the north and north-east of the St Leonards Reserve: in total 35 sections were sold during the 1850s, enlarging the developing St Leonards township. Subdivisions in the late 1850s and 1860s anticipated a boom period and provided allotments of various sizes, encouraging the building of cottages and terraces as well as villas and mansions.

St Leonards Park was envisioned by Mitchell in his original 1828 township plan, but it was Alderman William Tunks who planned and designed the gardens and layout. He fought the Carlow Street Enclosure Bill which would have allowed Carlow Street to cut the park in half in the 1880s. The area bordering the park, south from Ridge Street to Berry Street between Miller and Alfred streets, developed as an upper-middle-class neighbourhood. Here prominent businessmen, parliamentarians and doctors built grand Victorian and Federation houses on large blocks. Sadly, many of these homes were demolished for high-rise residential or commercial buildings from the 1960s onwards. There are however a few outstanding surviving examples at the northern end of Walker Street and in Ridge Street overlooking St Leonards Park, whilst others are located in the grounds of schools including Monte Sant' Angelo Mercy College and Wenona.

Local government began in the area with the formation of the Borough of St Leonards (1869) to administer the township, beginning the provision of utilities such as gas, water, roads, garbage collection, sewerage and sanitation. The three local boroughs (East St Leonards, St Leonards and Victoria) amalgamated to form the present council in 1890.

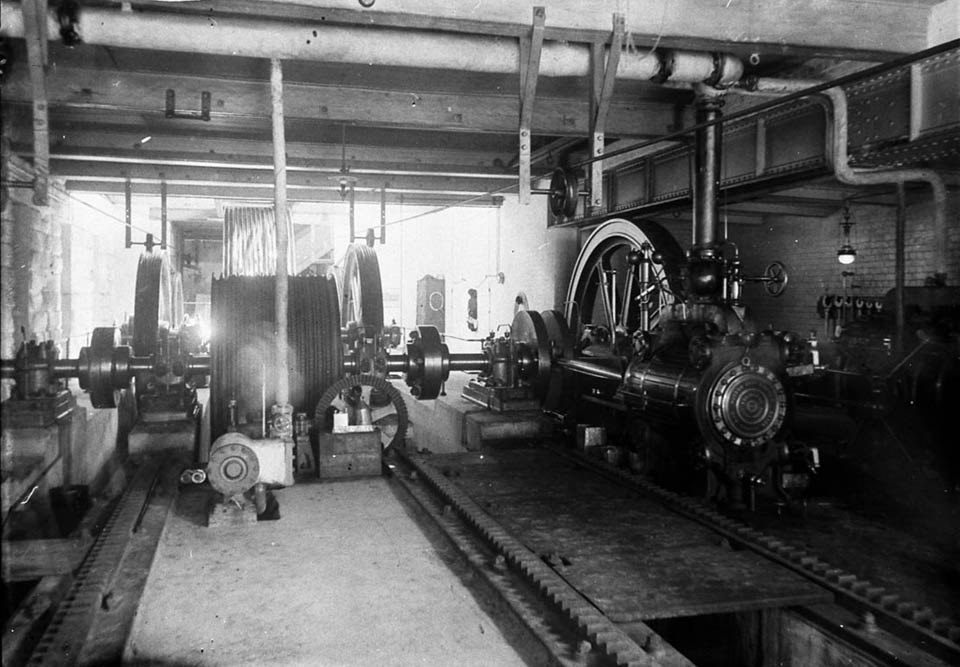

[media]In the mid-1880s, the intersection of Miller and Mount streets and Lane Cove Road (present day Victoria Cross) was the commercial and civic centre of the township. The development of a town centre was boosted by the construction of the cable tramway from Ridge Street to the ferry wharf at Milsons Point, via Miller and Alfred Streets. The foundation stones of the Post Office/Court House/Police Station complex, designed by government architect James Barnet, were laid in 1885 and the buildings opened in 1886. Opposite this complex was the former School of Arts, and nearby the Masonic (now Central) Hall, owned by the Wesleyan church. The former water hole and quarry at the corner of Blue and Miller streets, and practically the whole of Walker Street, were being developed. Business flourished in this area and banks, public buildings and shops were built in Miller, Mount and Walker streets.

Over the next 30 years, the population that settled in the township was a conglomerate of professional and commercial people, skilled tradesmen and labourers. The middle class built grand homes on the heights of North Sydney in the vicinity of the St Leonards Reserve. The medical fraternity established itself in and around Miller Street between Berry and Ridge streets, and this area became known as the 'Macquarie Street of the North Shore'.

The families of the township were also well served by educational establishments. The North Sydney Superior Public School (later the Greenwood Hotel) was erected in Miller and Blue streets in 1878, and expanded over time to serve a rapidly growing local population, eventually spawning North Sydney Girls' and North Sydney Boys' High Schools (1914 and 1912 respectively) and the North Sydney Demonstration School (1932). Religious schools for girls and boys were also established in the area before the end of the nineteenth century, and included Monte Sant' Angelo Convent (Miller Street), SCEGS Shore (Blue Street) and Wenona School (Walker Street).

Churches came to the township in the 1840s and 1850s. The Anglicans built the first St Thomas's in 1843 (the present grand Gothic church was erected in 1884), and the Jesuits established St Mary's in 1856. A church was built by the Methodists in 1863, and Presbyterians erected St Peter's in 1844 (rebuilt 1866). Entertainment venues included the Coliseum Theatre, built on the site of the cable tram winding sheds in Miller and Ridge streets in about 1912. It was later subdivided to become the Hoyts Union De Luxe Cinema and Independent Theatre in the 1930s.

Early twentieth century changes

In the wake of the Depression and the building of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932, building activity stalled, especially in the shopping centre in the heart of North Sydney. Land values dropped and population levels remained static. In 1926 the town hall was relocated to the heart of middle-class suburban North Sydney, taking over Dr Capper's Federation house at the corner of Miller and McLaren streets. The Lane Cove Road was extended to the Bradfield Highway and the newly constructed Sydney Harbour Bridge, resulting in the resumption and demolition of an entire street (Junction Street) and the North Sydney Methodist church on the Blue Street intersection. The road was also widened and renamed the Pacific Highway in 1932, at which time the present Victoria Cross intersection was formed. Council chose this name from a public competition held in 1939.

Development after the Depression mainly consisted of rebuilding. New Art Deco style hotels (Albert, Federal and Union Hotels rebuilt in the late 1930s), garages and public buildings replaced earlier buildings. Large Federation and Victorian houses were converted into boarding houses, with verandahs and balconies enclosed to provide additional bed-sitting accommodation and servants' quarters turned into flats. Despite this, the population declined across the suburb and municipality after World War II.

Postwar development

Low land prices (by comparison with the Sydney central business district) led several companies to build large headquarters in North Sydney. The headquarters of the Mutual Life and Citizens Assurance Company (MLC Limited) was built in Miller Street, opening in 1957, and the AMP built a substantial office block in Miller Street at the Blue Street corner. The MLC building was the first high-rise office block in North Sydney and the largest for a number of years after its construction: it was a pioneer building which influenced subsequent high-rise design in Sydney.

During the building boom of the 1960s, North Sydney was aggressively promoted as the 'Twin City' to Sydney. Cheap rents encouraged smaller firms to lease office space in the commercial centre. Between 1968 and 1973, 138 million dollars worth of office and bank building was commenced in North Sydney, causing the State Planning Commission to move to limit further growth in 1973. These developments had attracted insurance, advertising, computing and banking businesses to North Sydney.

Progress boomed again in the early 1980s. Companies were encouraged to build office towers in the formerly low-rise Victorian and Federation shopping centre, extending as far north as McLaren Street, and companies such as Philips, Sabemo, NRMA, Transfield and Ampol were attracted.

Directly to the east of this burgeoning commercial district, the Warringah Expressway was built. Opening in 1968, construction involved the demolition of nearly 500 houses and shops. North Sydney was split in half and many long-time residents forced out of the area. The completion of the expressway coincided with intense development in the central business district. With this, North Sydney came to resemble a 'Twin-City' rather than a suburban locality with a local shopping centre.

The building boom resulted in the wholesale demolition of the nineteenth-century township – Victorian and Federation shops, terraces, houses and public buildings disappeared from the streetscape. The residents of North Sydney began to object to the extent of development and the destruction of amenity and heritage, and a number of resident action groups were formed, including the North Sydney Civic Group. Dissatisfaction with the council in the late 1970s, particularly over plans for a new civic centre development to replace the existing council chambers, led to a rout of the existing council in the 1980 elections, with two-thirds of councillors replaced and Ted Mack elected Mayor.

There followed a period of reassessment of planning controls in North Sydney, to take into account the needs of residents living in adjoining streets and within the central business district and the large labour force working in the suburb. North Sydney Council, led by Mayor Mack, focused on reviving a sense of community, humanising and bringing a civic heart back to the suburb. A community identity that was to be distinctly North Sydney was fostered, via new street signs, bus shelters, colour schemes of public buildings, paving and street furniture, and rebuilding public facilities such as North Sydney Oval and Stanton Library. The pioneering North Sydney Heritage Study was released in 1982, a Precinct Committee system for citizen participation was implemented, and in 1989 the new Local Environmental Plan was gazetted.

The development pressure continues. However, in more recent times there has been a push to balance commercial development with conserving the environmental quality of the central business district and surrounding residential areas. In 2009 there are about 690 dwellings in the business district accommodating about 1,300 people. Future residential development will be in mixed-use buildings outside the commercial core, encroaching into the residential neighbourhoods. North Sydney had, in 2009, about 700,000 square metres of commercial floor space in the CBD, accommodating an estimated 35,000 workers (at a rate of 20 square metres per worker). It is expected that commercial space will grow by 250,000 square metres in the next 10 to 15 years, accommodating an additional 12,500 workers.

References

Rosemary Broomham, 'North Sydney, Another Brooklyn? Aspects of development during the boom period 1861 to 1891', History III Australian Urban History, 1980

John Griffin, North Sydney Diamond Jubilee Souvenir & Programme, North Sydney Municipal Council, North Sydney, 1928

Michael Jones, North Sydney 1788–1988, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards NSW, 1988

GVF Mann, North Sydney 1788–1938, North Sydney Municipal Council, North Sydney, 1938

Margaret Park, Designs on a Landscape: A History of Planning in North Sydney, Halstead Press and North Sydney Council, North Sydney, 2002

John Pert, 'The Foundation of St Leonards', The Push from the Bush: A Bulletin of Social History, September 1980, pp 37–50

Eric Russell, The Opposite Shore: North Sydney and its people, North Shore Historical Society and North Sydney Municipal Council, North Sydney, 1990

Notes

[1] John Griffin, North Sydney Diamond Jubilee Souvenir & Programme, North Sydney Municipal Council, North Sydney, 1928, p 33

.