The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Rachel Forster Hospital

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Rachel Forster Hospital

[media]The Rachel Forster Hospital was a general medical and surgical hospital that was run by women, for women, in Sydney. Doctors Harriett Eliza Biffin and Lucy Edith Gullett established it as an outpatient dispensary in 1922. The pioneering hospital, which became a public hospital in 1930, helped break down prejudice against women doctors by employing them and offering honorary positions and senior roles. In the second half of the twentieth century the hospital became a nurse training hospital and a centre for excellence in breast cancer treatment and orthopaedics.

The New South Wales Association of Registered Medical Women

In 1921 Sydney doctors Harriett Eliza Biffin and Lucy Edith Gullett, inspired by the Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital in Melbourne, planned to establish a women's hospital dedicated to women's health for Sydney. This had been a long-standing dream of other Sydney-based female physicians, such as the late Dr Dagmar Berne. [1]

Doctors Biffin, Gullett and Susannah (Susie) Hennessy O'Reilly organised a meeting to this end at the Women's Club at Beaumont House, 167 Elizabeth Street Sydney. In February 1921 they founded the New South Wales Association of Registered Medical Women, which by 1928 was known as the Medical Women's Society of New South Wales. The Association's first action was the establishment of a women-operated hospital for Sydney.

The New Hospital for Women and Children, Surry Hills

[media]With their own money, and funds from Biffin's mother Eliza and women doctors and their relatives, Biffin and Gullett purchased a small two-storey abandoned terrace house at 11 Lansdowne Street, Surry Hills for £1,000 on 3 January 1922. Their plans for a charitable outpatient dispensary for women and children were supported by established female doctors (Dame) Constance Elizabeth D'Arcy, Margaret Hilda Harper, Emma Buckley and Susannah (Susie) Hennessy O'Reilly. These doctors saw their university education as a means to improve working class women's health and living conditions.

It was an ideal time for the establishment of this type of hospital dispensary in Sydney, as infant and maternal welfare had become a subject of significant interest in Australia. The doctors also recognised that contemporary health care services neglected the needs of women who worked outside the home. Working class women at this time did not have adequate income to receive healthcare in their own homes, nor could they choose their own doctor. Many avoided seeking examination and treatment for general and gynaecological illness in public hospitals, because it meant consulting male doctors and male medical students. Surry Hills was the chosen location as numerous factories for working girls were nearby, it was close to Central Station, and it housed a crowded population living in sub-standard accommodation, including a large number of children urgently needing medical care.

The founding doctors repaired the terrace and named their primitive dispensary The New Hospital for Women and Children. Biffin was honorary treasurer of the committee and Gullett was honorary secretary. The New Hospital was founded with two aims – to serve poor women and children with general illness (excluding maternity issues), and to provide Sydney women medical students, graduates and specialists with the necessary professional clinical experience in medicine and surgery.

During the hospital's first year, 23 women doctors were appointed to honorary roles, and some senior male doctors attended in a medical and consultative capacity. The hospital provided two clinics each day – a venereal disease clinic and an eye clinic – and was open three evenings each week for women workers. The hospital focussed on preventive medicine.

The New Hospital gave working women a space where their medical needs and those of their children could be met together. Doctors made house calls in urgent situations. Patients paid sixpence per visit with funds raised through collection boxes, sales of bottles and a North Shore 'Shilling Drive.' Most of the furnishings and equipment were donated, with notable donations from the McIlrath, Pattinson and Gillespie families. [2]

During the hospital's annual general meeting for the year ended 1923, a committee of management appointed Biffin one of three vice-presidents. This autonomous committee of women met at the Women's Club and, from the very beginning, enjoyed full responsibility for administration and development of policy within the hospital.

The New Hospital for Women and Children was successful from its very first year with 7,596 patients treated in 1923, rising to 18,310 per year by 1926. [3]

Hospital experience for medical women

The New Hospital offered Sydney women medical students and physicians a workplace where they could receive general hospital experience. Here their medical training was valued and rewarded, and they could access specialist knowledge and work in honorary positions and senior roles that were critical to their career development. Such positions were difficult for women doctors to obtain, particularly after medical servicemen returned to Sydney after World War I.

Biffin's own harrowing experiences as a medical student informed her treatment of new women medical practitioners, and she ensured work was given to young women starting their careers. She claimed in 1923 'This hospital was started to afford an opportunity for experience and further training of women doctors – no other hospital affords this.' [4]

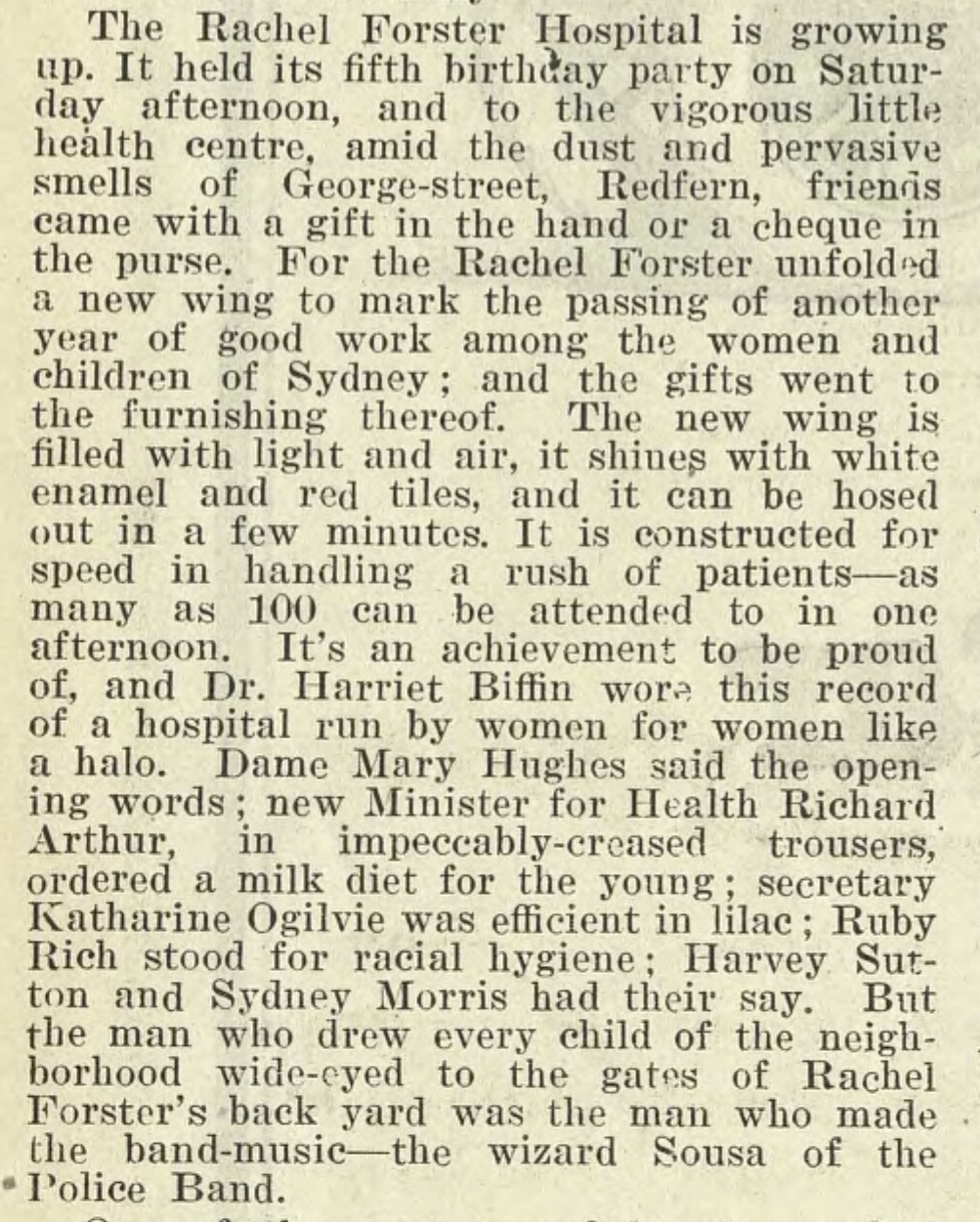

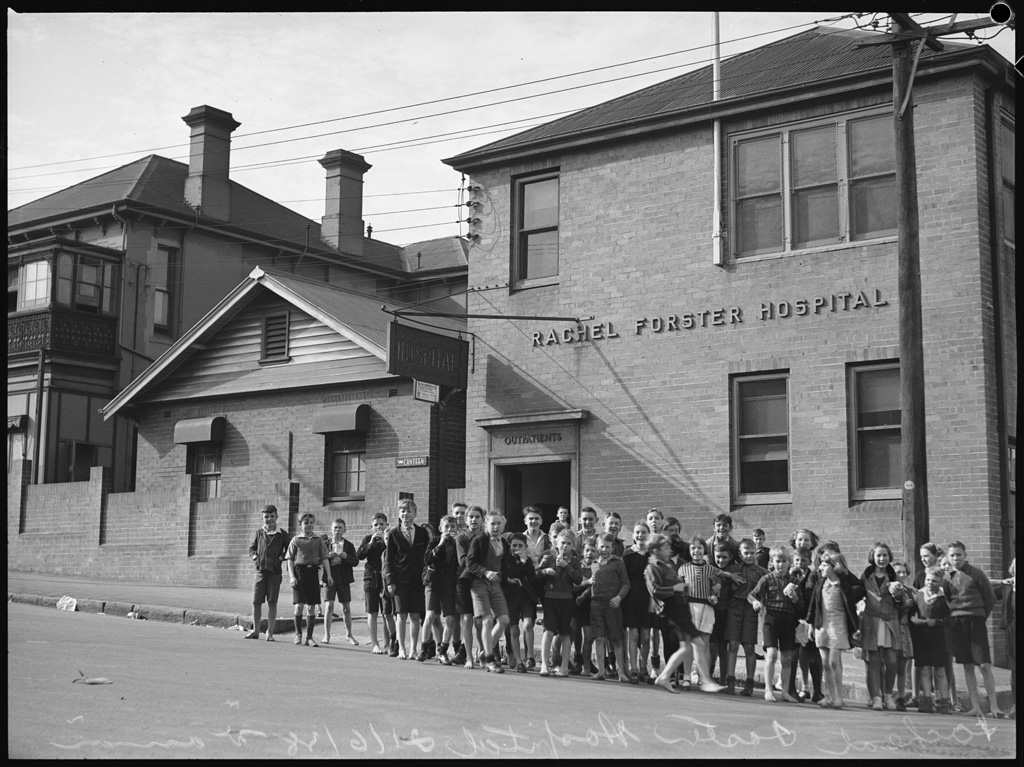

The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children, George Street Redfern

[media]The New Hospital for Women and Children became so popular with Sydney women that hopeful patients lined up in the street, waiting on the kerb or on suitcases. [5] It was clear that a larger site was needed. Biffin, Gullett and their philanthropists, mainly middle-class women, raised enough money to purchase a two-storey house with 13 rooms for £3,500 at 195 George Street, Redfern (Clyde House) in 1924. This was converted to a small inpatients' hospital with a single public ward, a dispensary and living quarters for staff. Rooms above the stables were converted into offices, and X-ray films were developed under the staircase in a cupboard dark room.

[media]Lady Rachel Forster, wife of the Governor General of Australia, officially opened the hospital on 22 August 1925 and to honour her, and her great interest in women's welfare, it was named 'The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children.' Dr Leonie Amphlett was the first resident medical officer and Mary Livingston was the first matron of the full-time resident nursing staff.

[media]To mark the hospital's first anniversary in 1926, Lady Sara Rachel Denison opened a new wing in Clyde House for six inpatient beds, further room for outpatients, and accommodation for the extra staff. New clinics for skin diseases, dental, antenatal, eye, physiotherapy, and ear, nose and throat were established. Twenty-eight women doctors now served in honorary roles, including surgery.

In 1927 the Board of Health added another wing for an outpatients venereal disease clinic for women and children, with Dr Elsie Dalyell appointed government medical officer a year later. The hospital became the main treatment site for venereal disease for women patients in New South Wales, and was serviced by medical officers appointed from the Department of Health.

Voluntary work and donations

[media]Women members of the public carried out a great deal of unpaid work during the early decades of the hospital. They volunteered as canteen clerks and the Girls' Secondary Schools Club served tea and biscuits to outpatients. Sydneysiders donated groceries, coal, flowers, linen, crockery and bottles for the dispensary, and women's sewing groups created baby clothes and completed mending. General egg appeals for patients were established with 'Egg Day' running over many years in Sydney schools.

During the 1920s and 1930s various Voluntary Hospital Centres were created in New South Wales to help raise the profile of the hospital through fundraising, and raised substantial amounts. The hospital walls, inside and out, filled with plaques and memorials that recognised this ongoing philanthropy, and wooden commemoration boards decorated the foyers. Wards and beds were frequently named after women doctors, in recognition of their work.

Public hospital status

A group of nine women doctors, led by Biffin and Gullett, made repeated attempts during the 1920s to have the hospital officially recognised by the NSW Hospitals' Advisory Board, although Biffin and Gullett disagreed with each other about how the hospital should be funded. Biffin believed it should remain administered by women and rely on philanthropic subscriptions. She was opposed to state financial assistance, fearing it would enable male involvement in the hospital's governance, whereas Gullett wanted the hospital to be able to receive the government subsidies other public New South Wales hospitals enjoyed.

In 1930, after an eight year struggle, the Rachel Forster Hospital was gazetted as a Second Schedule Hospital under the Public Hospitals Act 1929. This meant it could remain public, incorporated and be governed by its own board. The registration was ultimately achieved because of Dr Elsie Dalyell's plan to implement a successful 'model' outpatient venereal disease clinic for women on the hospital's new site, fully funded by government, the first of its kind in New South Wales.

New clinics and further expansion

[media]As it expanded, the Rachel Forster Hospital developed an outstanding reputation, especially in the areas of gynaecology and paediatrics. 'The Rachel' served generations of Sydney women and children and patients travelled from all parts of New South Wales, including the wealthier suburbs of Sydney, to access its unique services. Patient numbers increased during times of high unemployment.

In 1932 the first child guidance clinic in New South Wales was created, with Dr Irene Sebire appointed honorary psychiatrist, heading a clinic of two psychologists, an occupational therapist and a speech therapist. The clinic was groundbreaking for its time. By 1933, 41 women doctors served in honorary roles. In 1934 an almoner (social work) department was established by Kate Ogilvie as a response to the needs of Sydney women living in poverty during the Depression. It was the second in New South Wales and was registered as a centre for almoner training by the New South Wales Institute of Hospital Almoners. In the same year an operating theatre and 20-bed ward unit opened in a new building in George Street Redfern, plus an outpatient department for 200 daily attendances.

In 1936 Dr Mary Bertram established a rheumatism clinic offering sophisticated rehabilitation treatment to children and adolescents, and an honorary occupational therapist and a speech therapist were also appointed. In the same year a pathology department was established, enabling onsite work in the venereal disease clinic, with Dr Marjory Little appointed honorary pathologist and Dr Marie Hamilton pathologist. In the 1940s Ruby Board, vice-president of the hospital, created the Diabetes Association.

The Rachel Forster Hospital by this time was the critical institution for nurturing the professional lives of women physicians. Historian Louella McCarthy notes

Of the 320 women registered to practice medicine in New South Wales before 1940, almost 40 per cent had some kind of professional connection with the Rachel Forster Hospital. For a significant number of these women the hospital was their life's work. For many others it provided the possibility of senior positions not readily available elsewhere. By the late 1930s, the all-women Rachel Forster Hospital provided more honorary positions in one year than were available to women at all the other hospitals combined. [6]

The Rachel Forster Hospital expands to Pitt Street Redfern

The newly-acquired public hospital status, exploding patient numbers, and ambitious new goals meant the Rachel Forster Hospital urgently needed to expand its facilities. The hospital board applied to the Hospitals Commission for assistance to buy land and construct a modern inpatient hospital. It was the first time the hospital needed to go into debt. True to form, the Rachel Forster Hospital began servicing the debt with a City Appeals Office, the 'Buy a Stamp and Add a Brick Scheme', a tearoom at the 1940 Royal Easter Show and appeals to individual donors.

[media]Land was purchased at what is now 134-150 Pitt Street Redfern, on part of the original 100 acre (40 hectare) grant commonly known as 'Redfern's Farm', which had been made to convict surgeon Dr William Redfern by Governor Lachlan Macquarie in 1816. Dr Redfern's single-storey stone cottage 'Redfern Lodge' was demolished to build the Rachel Forster Hospital, although his original sandstock convict-built well still stands in the hospital basement and the camphor laurel tree he is commonly believed to have planted remains in the front yard.

[media]Leighton Irwin were appointed architects in 1933 and the foundation stone was laid on 24 August 1940. The large 124-bed modern hospital opened in December 1941 at a cost of £140,000, [media]with Dr Mary Puckey appointed chief executive officer (later general superintendent), the first Australian woman doctor appointed to this role. The hospital housed an emergency air raid unit, theatre wards and treatment bays in its basement. Lady Wakehurst, wife of the Governor of New South Wales, opened the hospital in December 1941, but due to World War II patients were not admitted until February 1942. Outpatients remained at Clyde House.

American interior decorator Mary Worthen carried out design, and Sydney artist Rhona Olive 'Pixie' O'Harris painted murals for the children's ward depicting fairies, sea creatures and Australiana. Sydney writer Miles Franklin made visits to the hospital to sign verses she had written to accompany the murals.

Women-led philanthropic activities such as fetes, 'Hospital Saturday Button Day', 2UW Carols by Candlelight Festivals, and bequests helped to fund the hospital's continuing expansion over the next decades.

The Sydney community reached out to involve itself in the day-to-day operation of the Rachel Forster Hospital. At the end of World War II the hospital was given an ambulance formerly used by the National Emergency Services which was converted to serve as an ambulance and delivery van for the collection of eggs from schools and bottles from various Sydney suburbs.

Training School for Nurses and University of Sydney teaching hospital

From 1942 until 1980 Rachel Forster Hospital was registered as a training school for general nurses and, from 1946 to 1949, was recognised as a University of Sydney teaching hospital for general medical and surgical undergraduate students. It was the first hospital of its type in Australia to be appointed as a training site for clinical teaching of medical students. In 1945 a new 18-room Nurses' Home and Cafeteria were built.

Lucy Gullet House, Bexley

Rachel Forster Hospital continued to respond to the needs of women patients from low-socioeconomic backgrounds. In 1946 the Victorian mansion 'Wanslea' in Bexley, formerly a home run by the Women's Australian National Service hostel, opened as a 22-bed convalescent home for underprivileged patients recovering after release from the hospital. [7] It was known as 'Lucy' after Dr Lucy Gullett, and operated until 1971, when it was sold. The funds raised established the 'Special Purposes and Trust Fund', and were spent on the Rachel Forster Hospital.

New outpatients department, specialist clinics and Australia's first mammogram

[media]Growth continued in the 1950s and 60s. In 1953 the 'The McKell Outpatients Department' was established with modern patient cubicles. Specialist clinics included eye, dental, skin, diabetic, psychiatric, orthopaedic, and a venereal disease clinic for adolescent girls and middle-aged women. Urology, neurosurgery, paediatrics and the almoner's department were included in this expansion.

The Rachel Forster Hospital was notable for founding a comprehensive breast clinic in 1950 under Dr Kathleen Cuningham, who went on to pioneer surgical procedures for breast cancer treatment, and Dr Marjorie Dalgarno, who performed Australia's first mammogram at Rachel Forster and implemented groundbreaking diagnostic radiology treatment there in 1955. The Rachel Forster Hospital was one of the first hospitals to establish a cancer detection clinic in the 1960s.

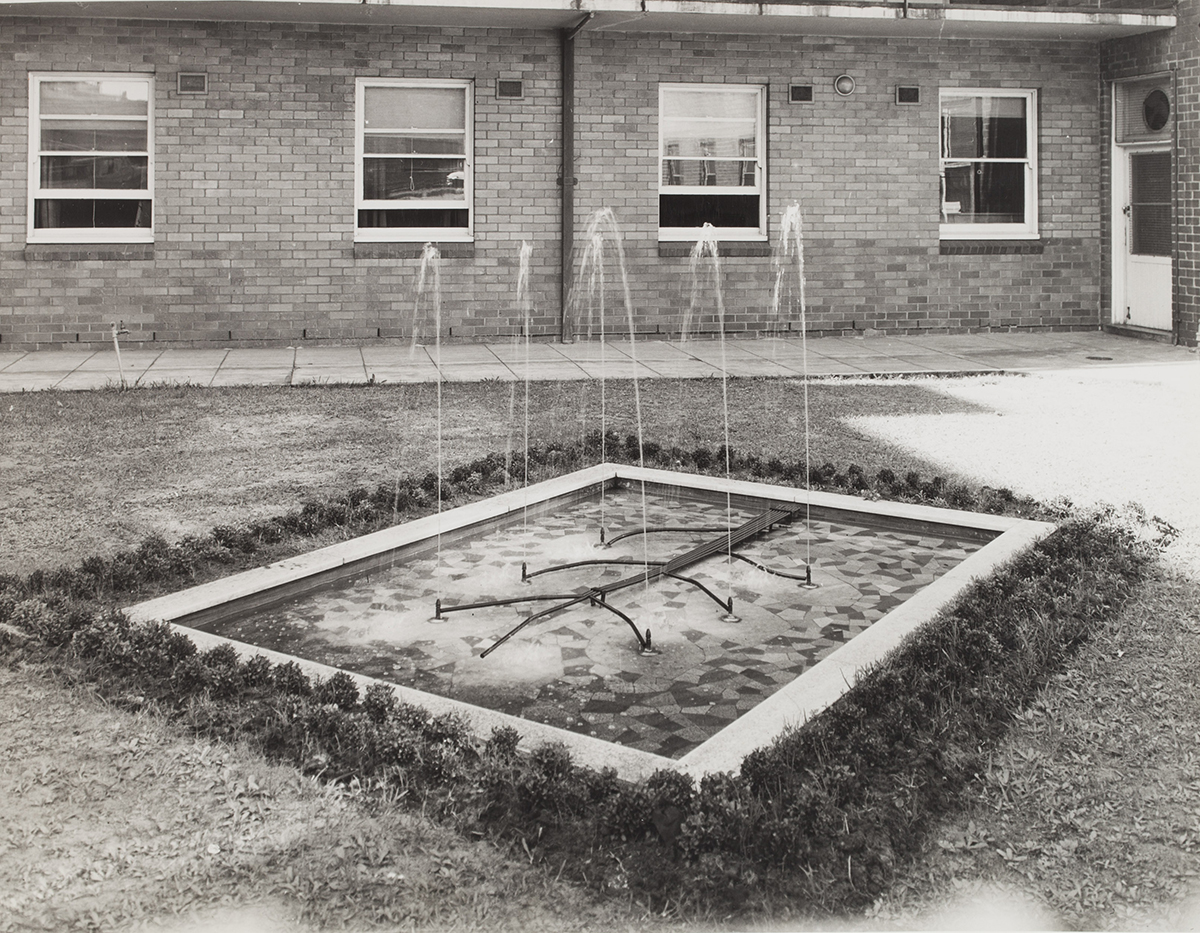

Pools of remembrance

[media]The Rachel Forster Hospital held a special place in the hearts of the Sydney community and this was recognised in the creation of outdoor memorials. In 1956 a fund was established to create a memorial garden and ornamental pool named the 'Pioneer's Memorial' in honour of the women doctors who founded the Rachel Forster. It was located at the back of the hospital. In the 1960s philanthropist and patient Nina Campbell donated another remembrance pool and fountain for the front garden named the 'Nina Campbell Pool of Reflection', in memory of her mother.

Male residents, patients and nurses

[media]For its four decades the Rachel Forster Hospital was founded, staffed and run by women for women. In 1962, when Lady Macarthur Onslow was appointed to the hospital Board, radical changes in policy began to take place. By 1965 women doctors found it easier to gain work as residents in Sydney hospitals and Rachel Forster was finding it difficult to recruit female honorary medical staff. This led to the appointment of its first male resident officers. In 1967 the hospital began admitting male patients into its first all-male ward in response to flats being built in the adjacent streets and a need for general hospital services for this community. Rachel Forster evolved into a small acute general hospital and in 1969 admitted its first male pupil nursing aide, and two years later enrolled male student nurses.

New developments

By the mid-1960s the hospital board decided a new focus was needed for the small hospital to ensure its survival and the hospital was remodelled as a centre of medical excellence serving its local ageing community.

Acute general services were retained. Innovative units such as The Kathleen Cuningham breast clinic continued to provide outpatient diagnostic and therapeutic services to women with benign mammary dysplasia and breast cancer. The Rachel Forster continued as a training hospital for women for its mastectomy rehabilitation service.

In 1965 a new pathology department opened and a year later the 'Ruby Board Clinic' was established for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes. In 1970 the cutting-edge 'Francis Gillespie Intensive Care Unit' opened.

In 1971 the Rachel Forster Hospital celebrated its 50 Year Jubilee. Resident medical officers from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital began to serve at Rachel Forster, and the University of Sydney requested consultants and honorary medical officers be shared between the two hospitals for its teaching program. In its Jubilee year a special 14-bed arthritis unit was transferred from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital to Rachel Forster, a partnership specialising in hip and bone replacement, and Dr John York was appointed head of the combined arthritis unit in 1974.

The implementation of Medibank by the Whitlam Labor government one year later led to closure of the Voluntary Hospital Centres, which had been developed to financially assist Rachel Forster. Their dedicated volunteers continued to work in an individual capacity within the hospital wards, outpatients, casualty and medical records.

By the late 1970s two housing commission blocks for aged residents were built next to the hospital to be close to its medical services.

The end of general nurse and nurse aide training

The Rachel Forster Hospital was a registered training school for general nurses and enrolled nurses aides and during the 1970s. Rachel Forster student nurses trained at additional hospitals including Royal Prince Alfred, Callan Park, Prince of Wales and Crown Street Women's Hospital. By 1980 the Rachel Forster was considered inadequate to meet the full range of nursing training needs and in that year general nurse training ended. This led to an increase in the employment of both registered nurses and enrolled nurse aides in the hospital. Later that year the hospital also ceased being a nurse aide training school. From 1985 the nursing department offered clinical experience for Sydney College of Advanced Education students.

Reduction of hospital beds

The 1970s and 80s were a time of immense change in the New South Wales public health care system and in 1978 the hospital board began to assess the future of Rachel Forster. A consultative committee chaired by Mrs WH Cullen sought viewpoints from the people of Redfern, South Sydney, departments and individuals within the hospital, local organisations and other hospitals about the future role of the hospital. Consultation through letters and constructive feedback gave the Board much-needed insight into patient and staff concerns, and led to changes in Board policy and improved relationships with the community.

The following year the Health Commission of New South Wales drastically cut services to public hospitals. The Rachel Forster Hospital lost 42 beds and a significant number of staff. The surgery of the gynaecological department was relocated to Crown Street Women's Hospital.

A specialist hospital for elective orthopaedics and Australia's first bone bank

The Health Commission of New South Wales continued to assess smaller metropolitan hospitals for their usefulness, and in response the Board decided that Rachel Forster should evolve into a specialist hospital for elective orthopaedics in 1979. Dr Harry Tyer headed the elective orthopaedic unit.

The orthopaedics and arthritis units greatly complemented each other and serviced the local community and the wider Sydney area. Elective orthopaedic surgery and medical staff were transferred from Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, which led to Rachel Forster becoming the largest tertiary referral centre for rheumatology and arthritis in the southern hemisphere. The occupational therapy department became vital to the hospital's new role.

The hydrotherapy pool opened to support these units in 1978. It cost $142,000, which was funded in full by the hospital Board and friends of the hospital. An onsite pool was vital to ensure the highest possible care for arthritic patients and meant they no longer needed to be transported to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital for hydrotherapy.

In 1984 Rachel Forster implemented Australia's first bone bank, under the supervision of Dr Harry Tyer.

Staff shortages and the New South Wales doctors' strike

During the 1980s Sydney public hospitals had difficulties attracting adequate numbers of registered nurses, resulting in a significantly increased workload for staff. Shortages were critical at Rachel Forster and throughout 1980-81 part-time registered nurses were employed to provide the necessary levels of patient care. The nursing division was notable for maintaining an exceptional reputation in the face of constant challenge and change.

Although the Rachel Forster had enjoyed long philanthropic support, funding was still a pressing issue. The New South Wales doctors' strike in 1984 illustrated growing frustration about ongoing cuts to hospital department staff and resources. In spite of this, the hospital's specialist units maintained their status, and continued to be known for their low infection rate in bone and joint surgery and hip replacements. Rachel Forster was the last public hospital specialising in bone and joint treatment in Sydney.

In its later years, 75 of the hospital's 89 beds were set aside for orthopaedic and arthritic conditions. By 1986, 36 beds were allocated to its Arthritis Unit, and 30 beds to its Orthopaedic Unit. The Rachel Forster maintained its character as a welcoming place, with arthritis patients in particular, who enjoyed the small hospital's personal approach and 'friendly warmth' during repeated visits. [8]

Although threatened with closure during the 1980s, a casualty service operated continuously with outpatient clinics in general surgery, podiatry, dietetics, urology, gastroenterology, ophthalmology, gynaecology and arthritis.

Community health services

The Rachel Forster Hospital enjoyed long and strong community support and effectively responded to changes taking place in the inner suburbs. During the 1970s Korean and Vietnamese migrants moved to the local community and the hospital provided interpreters as well as information classes about contraception and birth control for women from these communities.

Rachel Forster always cared for the Redfern Aboriginal community, and nurtured strong connections particularly in the late 1970s and 80s. Casualty and outpatients ran inpatient services for patients referred by the Aboriginal Medical Service as well as a clinic run by a Rachel Forster Hospital dietician. The Health Commission's Community Health Service for Aborigines also operated in Rachel Forster's George Street building. A training scheme was implemented to train Aboriginal welfare workers at the hospital and in 1978 one of three Aboriginal health workers in New South Wales was appointed to the hospital's social work department.

In 1983 the independent body Redfern House transferred its local community services to the hospital. These were utilised by Alcoholics Anonymous and the Redfern Community Health Care Centre, which provided psychiatric help, baby and school health services, counselling and home nursing. An alcoholism counsellor was appointed to the hospital to help with problems connected with alcoholism in Redfern. Social workers continued to play a vital role within the hospital's specialist units.

The hospital worked closely with students and offered them work experience. It mentored medical assistants from the Aboriginal Medical Centre, hosted Sydney College of Advanced Education nurses for practicums, and was used as a teaching space for the Dental Hospital's theatre sessions.

Rachel Forster administered by Royal Prince Alfred Hospital

The Board of the Rachel Forster Hospital was legislatively removed in 1986. Royal Prince Alfred Hospital and Area Health Service then administered the hospital. The Rachel Forster Hospital was threatened with closure during the 1990s and the 'Friends of Rachel Forster' created in 1992.

The closure of the Rachel Forster Hospital

[media]The Rachel Forster Hospital closed on 7 September 2000 and its inpatient and clinic facilities were transferred to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital. In 2007 the Redfern Waterloo Authority sold the hospital to Kaymet Corporation and commissioned Lippmann Partnership to prepare a plan for redevelopment of the 6923m² site into high-density residential apartments. The proposed redevelopment involves demolition of hospital buildings, some refurbishment of existing buildings, and maintenance of some façades with heritage significance. [9]

Historian Louella McCarthy notes

The hospital was a place of work and healing, but also a site of memory: a place to commemorate earlier practitioners, to celebrate contemporaries and to create a tangible sign of women's legitimate place in medicine. [10]

Yet in 2014 the Rachel Forster Hospital is at grave risk of demolition by neglect. It is covered in graffiti, and much of its interior is vandalised. Local residents and Sydneysiders continue to protest the destruction of this site of considerable historical significance.

References

Lysbeth Cohen. Rachel Forster Hospital: The First Fifty Years. Redfern: The Wentworth Press, 1984

Rachel Forster Hospital Sydney. Rachel Forster Hospital 1972-1986. nd

Notes

[1] The Brisbane Courier, 5 January 1898, 2

[2] Lysbeth Cohen, Rachel Forster Hospital: The First Fifty Years (Redfern: The Wentworth Press, 1984), 17

[3] Louella McCarthy, 'Idealists or Pragmatists? Progressives and Separatists Among Australian Medical Women, 1900-1940', Social History of Medicine, 16 no 2 (August 2003), 269

[4] State Records NSW, Department of Public Health, 10/43027, Correspondence Case Files 1928-42, Harriett Biffin to Dr Robert Dick, Director General of Public Health, 9 December 1923 cited in Louella McCarthy 'Idealists or Pragmatists? Progressives and Separatists Among Australian Medical Women, 1900-1940', Social History of Medicine, 16 no 2 (August 2003), 266

[5] The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children, Eighteenth Annual Report 1940 (Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Co., Ltd, 1940)

[6] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939, PhD Thesis, Department of History, University of New South Wales, 2001, 194

[7] 'Wanslea (1945 - 1950?)', Find & Connect Web Resource Project for the Commonwealth of Australia, Find & Connect web resource, http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/biogs/NE01205b.htm, viewed TIME \@ "d MMMM yyyy" 11 February 2015

[8] Rachel Forster Hospital Sydney, Rachel Forster Hospital 1972-1986, nd, 14

[9] Planning NSW Government website, Redevelopment of the Former Rachel Forster Hospital Site Preliminary Environmental Assessment, Lippmann Associates on behalf of the Redfern Waterloo Authority, http://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/asp/pdf/07_0029_rachelfoster_prelimasst.pdf and Appendices, Preliminary Heritage Assessment – Weir & Phillips, Lippmann Associates on behalf of the Redfern Waterloo Authority, http://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/asp/pdf/07_0029_rachelfoster_prelimasst_appendices.pdf, viewed 14 February 2013

[10] Louella McCarthy, Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939, PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2001, 194

.