The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Woollarawarre Bennelong

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Woollarawarre Bennelong

Woollarawarre Bennelong [media]was born about 1764 and grew up by the Parramatta river. At about the age of six weeks his parents named him after a fish. Before he could walk, his mother clasped him between her knees as she fished from her nawi, a canoe made of stringy-bark. He would have been about six years of age in April 1770 when Lieutenant James Cook and the botanist Joseph Banks spent a week at Botany Bay on the discovery ship, HMS Endeavour.

The Aboriginal boy was soon spearing wallumai (snapper) from the riverbank with his pronged fishing spear called a muting. One day he used a stone axe or mogo to cut a sheet of bark from a tree to build his own nawi. As a teenager he was initiated, when scars were raised on his chest and arms and his upper front tooth was knocked out to show that he was a man. He could now take a wife and hunt kangaroos and dingoes.

Woollarawarre Bennelong was a Wangal (Wanngal or Wahngal), a clan whose heartland on the Parramatta River logically centred on the shallow area of The Flats (now Homebush Bay) with its salt marsh, reed swamps and mudflats, a rich fishing ground and source of mud oysters, shellfish, crustaceans, ducks and other birds. Here Bennelong lived for the first half of his life. [1]

Wangal territory followed the south bank of the river eastward from The Flats to Memel (Goat Island), terminating at Gomora (Darling Harbour), where they bordered the harbour dwelling Cadigal. The Wallumedegal or Wallamattagal (Snapper Clan) occupied the north shore of the river, running east from near Burramatta (Parramatta) to the Lane Cove River. [2]

Bennelong was about 24 years old in January 1788 when a [media]convoy of British sailing ships brought some 1,000 men, women and children to Sydney Cove to establish the convict colony of New South Wales, an event that would change his life forever. In mid-1789, smallpox swept through the Indigenous population. Bennelong, who survived, said the epidemic killed half the Aboriginal people, including his first wife, whose name is not known. [3]

Two centuries have passed since Bennelong's death on 3 January 1813, in James Squire's orchard at Walumetta or Kissing Point, at Putney in the City of Ryde. [4]

After Arabanoo died from smallpox in May 1789, Governor Arthur Phillip sought once more to obtain information about the Aboriginal people, their country, life and language. He ordered First Lieutenant William Bradley of HMS Sirius to capture 'a Man or two'. [media]On 25 November 1789 at Kayeemy (Manly Cove) on the north side of Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour), two Aboriginal men, Bennelong and Colebee, were lured from a gathering on the beach by a gift of two big fish. Bradley, who painted a watercolour illustrating the abduction he supervised, wrote later:

They eagerly took the fish, they were dancing together when the Signal was given by me, and the two poor devils were seiz'd & handed into the boat in an instant…They were bound with ropes and taken by boat to Sydney Cove…It was by far the most unpleasant service I was ever ordered to Execute…all that could be said or done was not sufficient to remove the pang they naturally felt at being torn away from their friends; or to reconcile them to their situation. [5]

Thrust into history by his abduction, Bennelong would lead a tumultuous life, becoming the best known Aboriginal figure in the first decades of European settlement. More than a mediator and interpreter, he connects twenty-first century Australia with the social and spiritual Aboriginal world that existed before the English colony of New South Wales. His voice, filtered through accounts by First Fleet observers, speaks to us across the centuries and has been interpreted and misinterpreted in turn by historians, linguists and anthropologists. It reminds us that Sydney has an ancient Aboriginal past and for thousands of years belonged to the coastal clans who called themselves Eora ('People').

[media]He would sail 10,000 miles (16,093 kilometres) to England and back to his homeland, wear fashionable Georgian clothing such as jackets, breeches, hats and gloves while lodging in London and, like any tourist today, visit St Paul's Cathedral, the Tower of London and the Houses of Parliament at Westminster:

Bennelong resigned himself to his captivity when Colebee ran off after pulling the rope from his leg shackle on 12 December 1789. Captain John Hunter said he was 'much more cheerful after Co-al-by's absence, which confirmed our conjecture…that he was a man more distinguished in his tribe than Ba-na-lang'. [6]

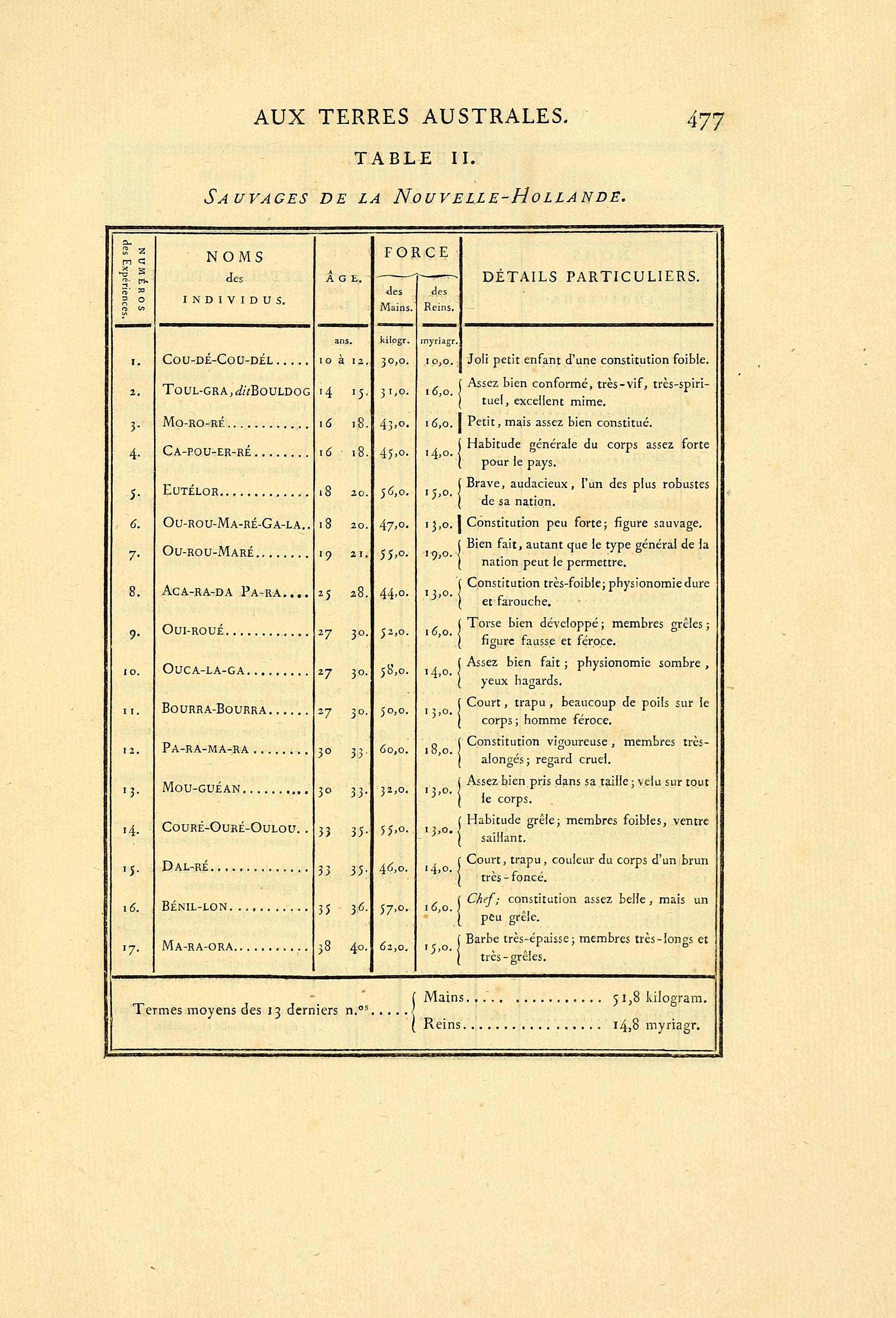

Watkin Tench judged Bennelong to be 'about twenty-six years old, of good stature, and stoutly made, with a bold intrepid countenance, which bespoke defiance and revenge'. A striking watercolour portrait of 'Ben-nel-long' by the unknown 'Port Jackson Painter' shows Bennelong 'when angry', with a flat nose and a mischievous twinkle in his dark eyes. [7] He was wiry and muscular, standing 5 feet 8 inches (170 centimetres) tall. Tench found that Bennelong measured 2 feet 10 inches (86 centimetres) around his chest and nine inches (23 centimetres) around his upper arm. [8]

The governor and his prisoner soon found ways to communicate and exchange information. Bennelong quickly learned simple English and adapted to European manners. He became a valuable informant, willingly providing information about Eora clans, language and customs. It was Bennelong who told Governor Phillip the names and locations of the Sydney clans and the Aboriginal name of Parramatta, which Phillip had at first called Rose Hill, but later renamed.

Bennelong's story has been plagued by myths: for example, that he 'collaborated' with the British, was 'taken to London to meet the king', was 'despised by his own people' and 'died in a street brawl'. These claims can be laid to rest from new research.

By nature Bennelong was mercurial: a joker and a mimic, quick to laughter or anger. He was also a canny politician who played a complex double game between his people and the governor. No collaborator, he was active in the resistance against the colonists before he agreed to 'come in' peacefully to the Sydney settlement in October 1790.

Names

Bennelong had five names, written with variations in spelling and order by the English journal keepers. For example, Phillip gave them as Wogultrowey, Wolarrabarrey, Baunellon, Boinba, Bundebunda; Philip Gidley King as Bannelon, Wollewarre, Boinba, Bunde-bunda, Wogletrowey; and David Collins as Ben-nil-long, Wo-lar-ra-bar-ray, Wo-gul-trow-e, Boinba and Bun-de-bun-da.

Bunde-bunda meant 'hawk', but the meanings of Bennelong's other names are obscure. 'Bennillong told me, his name was that of a large fish, but one that I never saw taken,' wrote David Collins. [9] According to Captain John Hunter, Vogle-troo-ye and Vo-la-ra-very 'were names by which some of his particular connections were distinguished, and which he had, upon their death, taken up.' [10]

Kin

Bennelong endeavoured to find a place for Governor Phillip and his officers in the binding kinship system of his people. Watkin Tench said Bennelong preferred the name Woollarawarre:

Although I call him only Bannelon, he had besides several appellations; and for a while he chose to be distinguished by that of Wo-lar-a-wàr-ee. Again, as a mark of affection and respect to the governor, he conferred on him the name of Wolarawaree, and sometimes called him Been-èn-a (father), adopting to himself the name of governor. This interchange of names, we found is a constant symbol of friendship among them. [11]

According to Atticus, writing in the Sydney Gazette in 1817, Bennelong's father Goorah-Goorah 'had separated from his mother Ga-gulh and was then living with Yahanua…' [12] In his second language notebook, Marine Lieutenant William Dawes noted the names of Bennelong and his sisters – Beneláng, Wariwéar, Karangárang, Wúrrgan and Munánguri. [13]

Bennelong forged political alliances with influential Aboriginal men through the marriages of his sisters Warreeweer (Wariwéar) and Carangarang (Karangárang). Warreeweer married Anganángan or Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan, who adopted the name of Collins from Phillip's aide David Collins.

Carangarang first married Yow-war-re or Yuwarry and they had a daughter named Kah-dier-rang and a son named Carangarany. Her second husband Harry was a younger man, identified by the French surgeon and pharmacist René-Primavère Lesson, who visited Sydney in 1824, as 'chef de la peuplade de Paramatta', that is, chief of the Parramatta people or clan. [14] Writing in 1828, the Reverend Charles Wilton said Harry was 'Chief of Parramatta'. [15]

On 3 February 1790, Governor Phillip took Bennelong by boat to the Look Out Post at Wollara (South Head) where, though hindered by his leg shackle, he threw a spear 90 metres against a strong wind 'with great force and exactness'. Returning, the boat stopped near Rose Bay, where Bennelong talked to an Aboriginal woman he was 'very fond of' called Barangaroo, who told him that Colebee was fishing on the other side of the hill. [16]

Escape

Bennelong's leg iron was taken off in April 1790 and he walked about freely with the governor, who gave him his short sword, which he buckled on and was 'not a little pleased at this mark of Confidence'. [17]

[media]He shared an upstairs room with a servant in Governor Phillip's house, built on the present site of the Museum of Sydney at the corner of Bridge and Phillip Streets. At two o'clock on the morning of 3 May 1790, Bennelong feigned illness and asked to go downstairs. Once outside, he stripped off his English clothes, jumped on an empty water butt and leapt the paling fence to freedom. [18]

Phillip notified Sir Joseph Banks:

Our Native has left us, & that at a time whe[n he] appeared to be happy & contented. This too is unlucky for we have all the ceremony to go over again with another, & I think that Mans leaving us proves that nothing will make these people amends for the loss of their liberty. The Girl (Boorong) who still remains said he went after a Woman, he had often mentioned & who I had as often told him to bring to live with him. [19]

Payback

On 7 September 1790, Bennelong and Colebee were among some 200 Aboriginal people feasting on a stranded whale on the beach at Kayeemy (Manly Cove), from which they had been seized. Bennelong promised to return to Sydney Cove if Governor Phillip, who was at South Head, would come to see him and sent Phillip a large chunk of blubber as a present.

When Phillip landed from his boat Bennelong shook his hand warmly and called him beanga (father) and made his accustomed toast to 'The King' when a bottle of wine was held up. What followed, recorded by the governor's aide Lieutenant Henry Waterhouse, who was an eyewitness, seems in retrospect to be a ritual spearing or 'payback' arranged by Bennelong and Colebee for the deprivation of their liberty.

Bennelong asked Waterhouse about an English woman 'from whom he had once ventured to snatch a kiss', then grasped him by the neck, laughed and kissed him, to show that he still remembered her. Phillip asked for a 'remarkably good' spear, but Bennelong, according to Waterhouse, 'either could not, or would not, understand him but took the Spear & laid it down in the grass'. Phillip described the spear as 'longer than common, and appeared to be a very curious one, being barbed and pointed with hardwood'.

Waterhouse realised that some 'nineteen arm'd men' had closed in around Phillip, David Collins, a sailor and himself. As they were about to leave, Bennelong introduced Phillip to a short, sturdy older man he called 'my very intimate friend'. As a sign of peace, Phillip threw his short sword to the ground and held out his hands, at which, said Waterhouse, the stranger seemed frightened and

seiz'd the spear that Bennalon had laid down in the grass, and immediately threw it with great violence…the spear struck the Governor, entered the right shoulder, and went through about three inches just behind the shoulder blade close to the back bone and I immediately concluded that he was killed and supposed there was not a chance for any of us to escape.

'For God's sake haul out the spear,' Phillip begged Waterhouse, who broke off the shaft with some difficulty. At Sydney Cove, Surgeon William Balmain extracted the wooden point from Governor Phillip's shoulder. Aboriginal men at Manly Cove identified the spearman as a carradhy or 'clever man' named Willemering from the Carigal (Garigal), 'a tribe residing at Broken Bay'. [20]

Phillip quickly recovered from his wound and on 17 September 1790 went by boat to meet Bennelong in his camp opposite Sydney Cove. He gave Bennelong a metal hatchet and fishing lines and returned the red jacket that he used to wear, while Barangaroo received a petticoat and other gifts. On 8 October 1790, Bennelong and some friends 'came in' peacefully to the Sydney settlement.

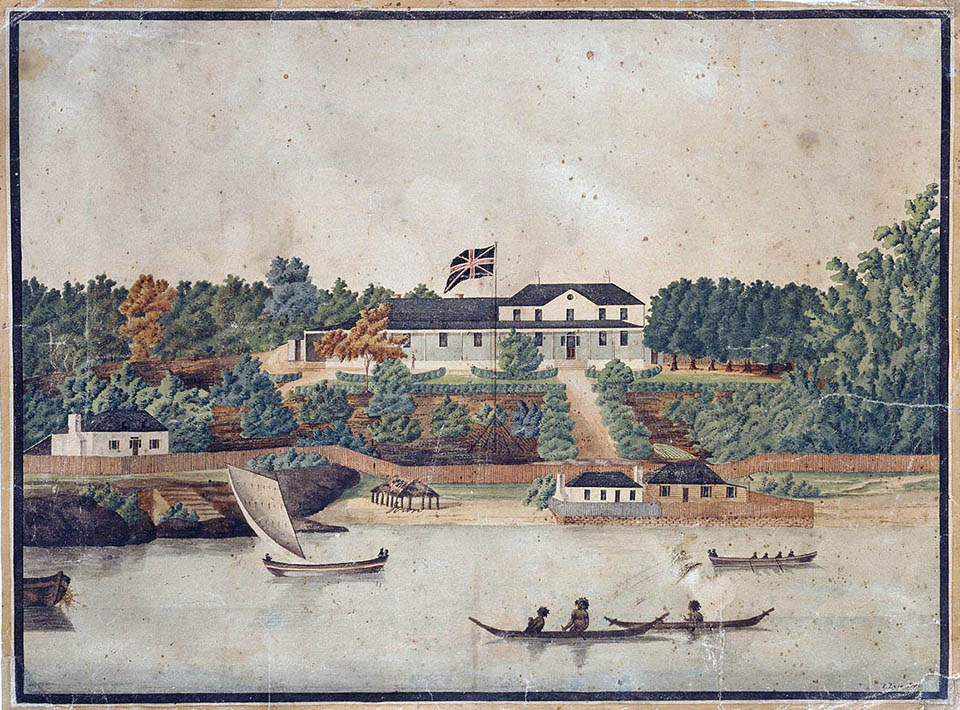

Bennelong and Colebee began to visit Governor Phillip regularly for dinner (a midday meal). At Bennelong's request, Phillip built him a brick hut 'on a point of land fixed upon by himself' on the headland at Tubowgulle, now Bennelong Point and the site of the Sydney Opera House. It was 12 feet (3.5 metres) square and had a tiled roof and an external fireplace. Phillip had a tin shield made for Bennelong, to ward off the spears of his enemies'. [21]

Wives

Shortly after his escape, Bennelong joined his second wife Barangaroo, the 'Woman, he had often mentioned' who, said David Collins, was 'of the tribe of Cam-mer-ray', the clan that occupied the north shore of Port Jackson. [22] Barangaroo was a widow, whose husband and two children had died. She gave birth to a baby girl named Dilboong (Bellbird), who lived for only a few months. [23] When Barangaroo died around the end of August 1791, Bennelong cremated her remains in Governor Phillip's garden adjoining Warrane (Sydney Cove). [24]

In November 1790, Bennelong was badly gashed on the forehead in a duel at Botany Bay with the Gweagal elder Mety, whose daughter Kurúbarabúla or Goroobarooboollo (Two Firesticks) he abducted and brought to Sydney. [25] William Dawes said she was about seventeen years old and the ngarángaliáng (younger sister) of Wárungin Wángubile Kólbi (Botany Bay Colebee), who had exchanged names with Colebee the Cadigal leader. [26] Phillip estimated her age at about fifteen. [27]

On 3 December 1791, Phillip wrote in a letter to Sir Joseph Banks in London:

I think my old acquaintance Bennillon will accompany me when ever I return to England, & from him when he understands English, much information may be attained, for he is very intelligent. [28]

Kurúbarabúla remained with Bennelong until he and his young kinsman Yemmerrawanne sailed to England aboard the convict transport HMS Atlantic with Governor Phillip on 10 December 1792. While Bennelong was away she became the companion of Caruey, a young Cadigal related to Colebee. [29]

London

Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne were [media]cared for in London by Henry Waterhouse's father, William Waterhouse (c1752–1822), a page to His Royal Highness, Prince Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland and a younger brother of King George III. [30] They lodged at Waterhouse's home at 125 Mount Street, Mayfair, close to both Grosvenor and Berkeley Squares. An ink sketch signed 'WW' (presumably William Waterhouse) now in the Mitchell Library, Sydney, shows Bennelong wearing the frock coat, ruffled shirt and spotted waistcoat tailored for him. [31]

Isadore Brodsky's statement in Bennelong Profile that on 24 May 1793 'Governor Phillip was presented at court together with Bennelong and Yemmerrawannie' cannot be substantiated. [32] Indeed, Brodsky reproduced a letter from Windsor Castle stating that 'there was no information about [Bennelong] in the Royal Archives'.

It is possible that Bennelong did meet King George informally on Monday 24 February 1794 when the royal family attended the double bill of The Tender Husband and Harlequin and Faustus at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden on the same night that Bennelong was there. The St James's Chronicle and other newspapers reported on 25 February:

London. Yesterday the Royal Family returned to town from Windsor, and in the evening honoured the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, with their presence.

Bennelong would at least have glimpsed the king in the Royal Box overlooking the stage.

Both Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne became ill at different times and were treated by Dr Gilbert Blane, a Royal Navy surgeon. In late September 1793, they were seen walking near Mount Street, frail, sick and dispirited, unable to walk 'without the support of sticks' and looking 'scarcely human'. One (Yemmerrawanne) appeared 'much emaciated', said the London Observer, which continued:

[T]hey seem constantly dejected, and every effort to make them laugh has been for many months ineffectual'. [33]

Nine days later on the 8 October 1793, Robert Jameson, a Scots naturalist aged nineteen, saw them at the Leverian or Parkinson's Museum in Southwalk and remarked in his journal that they had 'large mouths, thick lips and ill formed legs' and 'seemed to affect a kind of cheerfulness that was far from being real'. [34]

On 15 October 1793, Yemmerrawanne and Bennelong left Mayfair and were taken by stagecoach to the small village of Eltham in Kent, three miles south of Greenwich. They lodged there at the home of Edward Kent, employed by Viscount Sydney (Thomas Townshend, 1733–1800). On 16 April 1794, Yemmerrawanne, who had lain gravely ill for months at Eltham, somehow managed to regain sufficient strength to visit the Houses of Parliament with Bennelong. The Aboriginal voyagers caused quite a stir when they attended the debates in the House of Commons, according to the World (17 April 1794):

Two of the natives of Botany Bay were present yesterday at Mr. HASTINGS'S Trial. Their appearance excited much curiosity.

When introduced to the Speaker, Henry Addington (Viscount Sidmouth, later Prime Minister), 'They appeared to be highly pleased, and answered acutely several questions,' the Sun reported. The cost of their excursion, described as 'Expenses to Mr Hastings Trial', was six shillings. In 1788, Warren Hastings (1732–1818), first Governor General of India, was impeached by Edmund Burke (1729–97) in the House of Lords and the trial dragged on for years.

Bennelong's sense of humour had revived. A droll story he told about his Bulla Murree Deein ('two big women') was well received in Sydney in 1790. In London three years later he joked with the Oracle's reporter about having a trio:

One of them, a very merry fellow, says, he regrets nothing so much as the inconvenience he finds in the absence of his three wives, for whom he had not yet been able to find a substitute in this country.' [35]

[media]After a long illness, on 18 May 1794, Yemmerrawanne died of a lung ailment and was buried in the churchyard of St. John's in Eltham, now a suburb of South London. He was only nineteen.

Return

Bennelong went on board the 304 ton HMS Reliance at Chatham on the River Medway in Kent on 30 July 1794. [36] 'Bannelong' appears in the ship's muster under 'Supernumeraries borne for Victuals only' with James Williamson and Danl Paine (master shipwright Daniel Paine) on 15 September 1794. [37]

Six months later, on 25 January 1795, Captain John Hunter, appointed second governor of New South Wales, said he feared that the 'Surviving Man (Banilong)' was so ill and 'broken in Spirit' that he might die. [38] After a further delay, the voyage began on 2 March and ended on 7 September 1795 when Reliance dropped anchor in Sydney Cove. Bennelong had been away for two years and 10 months, 18 months of which he spent on board ships, either at sea or in the docks. His brick house at Bennelong Point was demolished in November 1795, two months after his return to Sydney.

Bennelong [media]had no desire to return to Europe, as he declared on 29 August 1796 in a letter addressed to 'Mr. Phillips, Steward to Lord Sidney', but probably meant for Governor Phillip (as a steward) to pass on to Lord Sydney. 'Not me go to England no more. I am at home now.' [39]

John Washington Price, an Irish-born surgeon on the convict transport ship Minerva, saw Bennelong and wrote in his journal on 19 January 1800:

I visited the Governor [John Hunter], at whose house I saw Bennillong, who had been to England some years ago, he was after returning from the woods where he frequently goes among his native friends, & spends 14 or 16 days at a time; he speaks English tolerably well, admires the English customs, and is exceeding polite & agreeable. [40]

Fresh evidence refutes the repeated historical claim that in the second part of his life his own people despised Bennelong. In 1797, Bennelong officiated at an initiation ceremony on the north shore (as he had previously in 1790). Sometime after 1803, Bennelong left the Sydney settlement and re-established his authority as leader of a 100-strong Aboriginal group on the Parramatta River west of Ryde. [41] He continued to take part in frequent ritual revenge battles staged in the streets of Sydney and was often wounded.

About this time Bennelong remarried and had a son named Dicky or Dickey, who was adopted and baptized as Thomas Walter Coke, by the Reverend William Walker. [42] Before his death in 1823, the youth married an Aboriginal girl named Maria, later known as Maria Lock, but they had no children.

[media]It is obvious that Bennelong, who had seen at first-hand the best and worst of European civilization, chose to reject it. In 1802, when the French mariner Pierre Bernard Milius invited him to sail to France, Bennelong replied that 'there was no better country than his own and that he did not wish to leave it'. [43] In The Present Picture of New South Wales, David Dickinson Mann, who left Sydney in March 1809, said Bennelong had 'taken to the woods again, returned to his old habits, and now lives in the same manner as those who have never mixed with the civilized world…he prefers to taste the liberty amongst his native scenes…' [44]

Bennelong [media]spent his last years in the orchard of the friendly ex-convict brewer James Squire (c1755–1822) at Kissing Point. Squire was granted 30 acres (12 hectares) of land at the Eastern Farms in 1795 and by 1799 was brewing his own beer and owned the Malting Shovel public house.

Bennelong's obituary in the Sydney Gazette, the first printed reference to him for seven years, was scathing and patronizing:

Bennelong died on Sunday morning last at Kissing Point. Of this veteran champion of the native tribe little favourable can be said. His voyage to and benevolent treatment in Great Britain produced no change whatever in his manners and inclinations, which were naturally barbarous and ferocious.

The principal officers of Government had for many years endeavoured, by the kindest of usage, to wean him from his original habits and draw him into a relish for civilised life; but every effort was in vain exerted and for the last few years he has been but little noticed. His propensity for drunkenness was inordinate; and when in that state he was insolent, menacing and overbearing. In fact, he was a thorough savage, not to be warped from the form and character that nature gave him by all the efforts that mankind could use. [45]

The only dependable account of Bennelong's death was given in 1815 by Old Phillip, brother of Gnung-a Gnung-a Murremurgan 'Collins', to ship's surgeon Joseph Arnold, who wrote in his journal 'old Bennelong is dead, Phillip told me he died after a short illness about two years ago & that they buried him and his wife [Boorong] at Kissing point'. [46]

A traditional ritual revenge combat was fought in Sydney not long after Bennelong's death. It was not reported in the Sydney newspapers, but was witnessed by 'a free merchant of India', a passenger on the schooner Henrietta , who wrote a letter dated 'off Bass's Straits, 17th April, 1813', which was printed in the Caledonian Mercury in Edinburgh on 26 May 1814. The writer stated that:

Lately, in the vicinity of the town [Sydney], a battle took place, where about 200 were engaged, I believe in consequence of the death of the celebrated Bennelong, who visited England some years ago, and was taken great notice of. The spears flew very thick, and about thirty men were wounded. [47]

'Both Ben-ni-long & his Gin [wife] are interred in the Garden of this farm' wrote Royal Navy lieutenant Allen Francis Gardiner (1794–1851), of HMS Dauntless, who on 31 July 1821 attended a 'Corrobera' (corroborree) near Squire's Farm that preceded a ritual revenge battle.

It is likely that Colebee's nephew Nanbarry, who died on 12 August 1821, was wounded in the ensuing combat. [48] Nanbarry was buried at his own request in the same grave as Bennelong and Boorong. There could be no greater mark of respect. [49]

References

William Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales: The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969

John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island: With the Discoveries Which Have Been Made in New South Wales and in The Southern Ocean Since The Publication Of Phillip's Voyage, Compiled From The Official Papers, John Stockdale, London, 1793

Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, Including an Accurate Description of the Colony; of the Natives; and of Its Natural Productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793

David Collins, An account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country, vol. 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798

Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora, Sydney Cove 1788–1792, Kangaroo Press/Simon & Schuster, East Roseville, 2001

Keith Vincent Smith, 'Bennelong Among His People', Aboriginal History 33, Australian National University ePress, 2009

Notes

[1] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, p 560

[2] Bennelong, quoted in Arthur Phillip to Lord Sydney, 13 February 1790, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, p 308

[3] Bennelong, quoted in Arthur Phillip to Lord Sydney, 13 February 1790, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol 2, p 308

[4] The Sydney Gazette, 9 January 1813

[5] William Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales: The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the Public Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, pp 181 et seq; William Bradley, Taking of Colbee and Benalon, 25 Nov.r1789, watercolour, Mitchell Library collection, State Library of New South Wales, ML safe 1/14

[6] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island: with the Discoveries Which Have Been Made in New South Wales and in the Southern Ocean since the Publication of Phillip's Voyage, Compiled from the Official Papers, John Stockdale, London, 1793, pp 168–9

[7] Port Jackson Painter, Native name Ben-nel-long, as painted when angry after Botany Bay Colebee was wounded, c 1790, watercolour, no 41, Watling Collection, Natural History Museum, London

[8] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, Including an Accurate Description of the Colony; of the Natives; and of Its Natural Productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, p178

[9] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, p 562

[10] John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island: with the Discoveries Which Have Been Made in New South Wales and in the Southern Ocean since the Publication of Phillip's Voyage, Compiled from the Official Papers, John Stockdale, London, 1793, p 168

[11] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, Including an Accurate Description of the Colony; of the Natives; and of Its Natural Productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, p 35

[12] The Sydney Gazette, 29 March, 1817

[13] William Dawes, ‘Vocabulary of the language of N.S. Wales in the neighbourhood of Sydney…, Notebook B, 1791, Marsden Collection, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, p 9.4, MS 41655 (b); Dawes's notebooks are online at http://www.williamdawes.org

[14] René Primavere Lesson, Voyage Autour du Monde, sur la Corvette La Coquille, P Pournat Freres, Paris, 1838, p 277

[15] Reverend CPN Wilton, Australian Quarterly Journal of Theology, Literature and Science, Sydney, 1828, p 233

[16] William Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales: The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, pp 187–8

[17] Philip Gidley King, '9 April 1790', Journal of PG King, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, MS C115

[18] Daniel Southwell to his uncle Reverend Weeden Butler, 27 July 1790, Southwell Papers, British Library, London, MSS 16388

[19] Arthur Phillip to Sir Joseph Banks, '26 July 1790', Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 37: Letters, with related papers and journal extract, received by Banks from Arthur Phillip, 1787–1792, 1794–1796, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MS A81

[20] Based on Henry Waterhouse in William Bradley, A Voyage to New South Wales: The Journal of Lieutenant William Bradley RN of HMS Sirius, 1786–1792, facsimile reprint, Trustees of the State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, 1969, pp 225–30; and Henry Waterhouse in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island: with the Discoveries Which Have Been Made in New South Wales and in the Southern Ocean since the Publication of Phillip's Voyage, Compiled from the Official Papers, John Stockdale, London, 1793, pp 459–65

[21] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson, in New South Wales, Including an Accurate Description of the Colony; of the Natives; and of Its Natural Productions, G Nicol and J Sewell, London, 1793, p 83

[22] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, p 560

[23] 'The melancholy cry of the bellbird (dil boong, after which Bennillong named his infant child)', John Hunter in David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, reprinted by Reed in Association with the Royal Historical Society, Sydney, 1975, p 120

[24] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, p 506–07

[25] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, pp 605–07

[26] William Dawes, ‘Vocabulary of the language of N.S. Wales in the neighbourhood of Sydney…, Notebook B, 1791, Marsden Collection, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, pp 9.1–2; 45.5, MS 41655 (b); Dawes's notebooks are online at http://www.williamdawes.org

[27] Arthur Phillip in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island: with the Discoveries Which Have Been Made in New South Wales and in the Southern Ocean since the Publication of Phillip's Voyage, Compiled from the Official Papers, 1793, p 486

[28] Arthur Phillip to Sir Joseph Banks, '3 December 1791', Papers of Sir Joseph Banks, Series 37: Letters, with related papers and journal extract, received by Banks from Arthur Phillip, 1787–1792, 1794–1796, pp 34–44, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MS A81

[29] John Hunter in David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales: With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners, &c. of the Native Inhabitants of That Country, vol 1, T Cadell and W Davies, In the Strand, London, 1798, reprinted by Reed in Association with the Royal Historical Society, Sydney, 1975, vol 2, p 16

[30] William Thomas Parke, Musical Memoirs: Comprising an Account of the General State of Music in England, New Burlington Street, London, 1830, p 120

[31] William Waterhouse 'WW', Banalong, [Bennelobg], c1793, pen and ink wash, Dixson Library collection, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, DGB 10, f.13

[32] Isadore Brodsky, Bennelong Profile, University Cooperative Bookshop, Broadway, Sydney, 1973, p 64; This claim is repeated online in Barani: An Introduction to the Aboriginal History of the City of Sydney website http://www.sydneybarani.com.au/main.html

[33] London Observer, 29 September 1793

[34] Robert Jameson, 'Journey of a Voyage from Leith to London 1793', quoted in Jessie M Sweet, 'Robert Jameson in London 1793', Annals of Science, no 23, London, 1963, p 102; information provided by Richard Neville, Mitchell Librarian, State Library of New South Wales

[35] The Oracle and Public Advertiser, London, 19 April 1794, in James Bonwick, Bonwick Transcripts, 1641–1892, Being a Collection of Transcripts from Material Mainly in the Public Records Office, London, and From Other Sources Relating to New South Wales and Australia, Transcribed by James Bonwick and Assistants, 1887–1902, Mitchell Library collection, State Library of New South Wales, BT 59, p 114

[36] Letter from John Hunter to John King at the Admiralty, 5 August 1794, Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies, The National Archives, Kew, London, CO201/pt 2, pp 77–8

[37] HMS Reliance Muster 1794, 'Royal Navy Ships' Musters (Series I)', Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies, The National Archives, Kew, London, PRO 7006, ADM 36/10891

[38] Letter from John Hunter to John King at the Admiralty, 25 January 1795, Records of the Admiralty, Naval Forces, Royal Marines, Coastguard, and related bodies, The National Archives, Kew, London, PRO C0201/12:3

[39] 'Bannolong' in Franz Xaver von Zach (ed), Correspondenz zur Beförderung der Erd- und Himmels-Kunde [Monthly Correspondence for the Promotion of Geography and Astronomy], im Verlag der Beckerischen Buckhhandlung, Gotha, Germany, 1801, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MRB137, pp 373–5; see also KV Smith, 'Bennelong's Letter', The Australian, 29 December 2012

[40] JW Price, The Minerva Journal of John Washington Price, MUP Press, Melbourne, 2000, p 146

[41] Joseph Holt, Holt, Joseph – Life and adventures of Joseph Holt, Known By the Title of General Holt in the Irish Rebellion, 1798–1814, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MS A2024; see also Joseph Holt in Peter O'Shaunessy (ed), A Rum Story – The Adventures of Joseph Holt, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1988, pp 68–72

[42] The Sydney Gazette, 6 February 1823

[43] Nicolas Baudin, Mon Voyage aux Terres Australes: Journal Personnel du Commandant Baudin / Texte Établi par Jacqueline Bonnemains avec la Collaboration de Jean-Marc Argentin et Martine Marin, Imprimerie Nationale Editions, Paris, 2000, p 49

[44] DD Mann, The Present Picture of New South Wales, John Booth, London, 1811, pp 46–7

[45] The Sydney Gazette, 9 January 1813

[46] Joseph Arnold, 18 July 1815, Joseph Arnold Journals, 1810–1815, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MS C720, p 401

[47] 'New South Wales', Caledonian Mercury, 26 May 1814

[48] Allen Francis Gardiner to his father Samuel Gardiner, Sydney Cove, '1 August 1821', Letters from The South Seas Written During the Years 1821–1822, Mitchell Library manuscript collection, State Library of New South Wales, MSS 8112, p 49

[49] The Sydney Gazette, 8 September 1821

.