The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Great Strike of 1917

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Great Strike of 1917

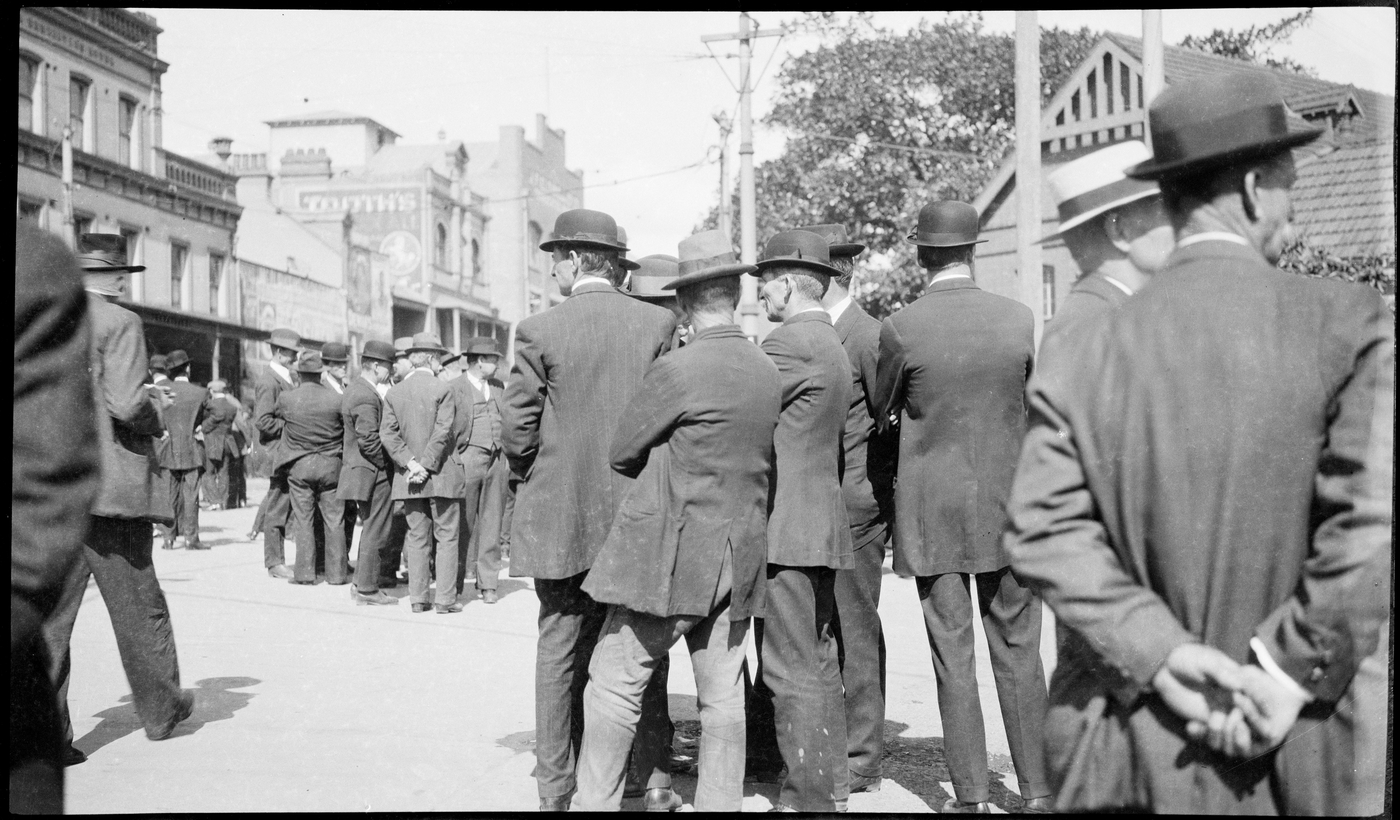

[media]The Great Strike of 1917 is regarded as one of Australia’s largest industrial conflicts. The strike erupted on the New South Wales railways and tramways in August 1917 in response to the introduction of a new way of monitoring worker productivity. Thousands of working people across a range of industries were mobilised as the strike spread throughout New South Wales and Australia. In Sydney, there were extraordinary street marches and demonstrations led by the strikers and their supporters. On the other side of the political and class divide, strikebreakers were recruited to keep transport and industry running. While the strike lasted for only six weeks, its consequences – political, social and cultural – lingered for decades, shaping the political consciousness of generations.

The trigger

The Great Strike of 1917 began on 2 August when around 5,780 New South Wales railway and tramway employees downed tools to protest against the new job timecard system that had been introduced a few weeks before. Most were from the Eveleigh Railway Workshops and the Randwick Tramway Workshops.[1]

The timecard system added a new layer of management in the workshops, and was considered an affront to the skill and craftsmanship of rail and tram employees. There were three kinds of cards, coloured blue, white and red, representing different classifications of work: general, job and routine. The timecards were intended to be filled out by the sub-foremen as a way to record and monitor worker productivity on the state's railways and tramways.[2]

Almost two-thirds of railway and tramway employees in New South Wales went on strike. The workers saw the introduction of the card system as a ‘direct attack on collective work practices and trade union principles’.[3] For Edward Kavanagh, the Secretary of the New South Wales Trades and Labour Council, ‘one of the objections [to the timecards] was that it was the thin edge of the wedge of the first instalment of what is termed the Taylor Card System of America’.[4] Taylorism was a tool for monitoring industrial work practices and maximising worker efficiency that was influential in the development of Fordism, the theory and practice of assembly line mass production first used by Henry Ford to manufacture cars in America in the early 20th century.

The strike spreads

The strike spread to other industries in towns and cities across Australia through the imposition of ‘black bans’ and sympathy actions. A black ban was when trade unions and workers refused to distribute products handled by strikebreakers. Coal was ‘black’, which meant that many of the state’s collieries were idle, as were coal gas works across Sydney, which led to power blackouts. There were food shortages because staples like butter, meat and sugar were declared ‘black’, and because shipping was held up.

Sympathy actions mobilised workers across a range of industries, extending beyond the railways and tramways, including those in maritime trades, gas workers and coal miners. Overall, it is estimated that around 77,350 workers across New South Wales ‘went out’. Just under half of those striking were maritime workers and miners, while a quarter were rail and tram workers, showing the strength of support for the strike action from workers in unrelated industries.[5]

The strike disrupted the regularity of daily life and made day-to-day living harder. Because it had started on the railways and tramways, there was limited public transport in Sydney and across New South Wales. For Gwen Green, 17 years old at the time of the strike, it was ‘awful, everything stopped. I can’t describe how dreadful it was, because bread wasn’t being made, trams and trains ceased, living was impossible for those particularly who didn’t have any reserves … it really was a very bad time.’[6]

Social protest

One feature of the 1917 strike was the social protest that accompanied it, including frequent large-scale street processions and public meetings. Weekly gatherings in The Domain attracted upwards of 100,000 people, and not just the striking men, but women and children too. These orchestrated public gatherings at The Domain represented around one-seventh of the overall population of greater Sydney in 1917, equivalent to 650,700 people taking to the streets today. This social protest built on forms and traditions of public engagement dating from the 19th century.

[media]The strike action took up the public space with increasing intensity. Within a week, there were daily street processions. There were at least two defined routes through central Sydney. Strikers and their supporters met at Eddy Avenue near Central Station, close to a trio of buildings on the corner of George Street and Rawson Place considered the ‘nerve centre’ of the labour movement.[7] From there, the processions travelled north along George Street to Park Street, then north down College Street to reach The Domain. The alternative route went via Wentworth Avenue and Elizabeth Street.

Brass bands played marching songs, banners were held aloft, participants sang songs both popular and stirring, and there were calls to action. The processions were long, often taking around an hour to pass a certain point. Traffic was invariably held up.

Street processions were a type of public performance that was understood, accepted and tolerated across societal boundaries in the early 20th century. Violence was the exception rather than the rule, and indeed the decorum and order of the processions was often remarked on in the press.[8] The main complaints were about language and ‘hooting’, with the most potent term being ‘scab’.[9]

Yet occupancy of the street had both symbolic and real power. The ‘authorities’ considered the public protest as a ‘safety valve’, to give voice to the strikers and to channel their dissent and dissatisfaction. In early September, for example, the Inspector-General of Police ‘announced that it was not considered desirable that the strikers' procession on each day should be stopped, though it was causing some disturbance of regular traffic in the streets’.[10] There was reluctance to stop the street processions and mass-gatherings entirely.

[media]Women were on the frontline of social protest. They were workers too, and economic hardship caused by male workers going on strike affected whole family units. On 9 August 1917, within a week of the strike breaking out, thousands of women marched from the industrial suburbs of Marrickville, Newtown and Enmore, via Eddy Avenue, to Parliament House. A deputation of six women met with the then Assistant Premier, George Fuller. The deputation claimed to represent some 15,000 women: the wives of strikers, but also ‘women who entered the industrial field to earn their own living’.[11]

Political action and divided loyalties

These were heady days. The strike took place against the backdrop of World War 1, by then in its fourth year. There were heavy casualties at the front. The war exacerbated the impact of new technologies and changing social values.

Poverty was rife on the homefront. The cost of living had gone up during the war while wages stayed the same. There were government and community fears about a possible insurgency by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), nicknamed the ‘Wobblies’. The federal government had passed the Unlawful Associations Act in 1916, which effectively outlawed the IWW, and sent a message that the government would not accept dissent.[12] The workshops at Randwick were considered a hotbed for the ‘Wobblies’. Other world events that echoed the dissent of the times included the Irish Rebellion of 1916 and the Russian Revolutions of 1917. Locally, the conscription debates divided Australian society along class, gender and sectarian lines. Loyalties were tested.[13]

Breaking the strike

On the other side of the political and class divide, striking during wartime was considered unpatriotic and disloyal. Middle-class men and women, farmers, university students and teenage schoolboys attempted to break the strike by doing the jobs of the striking men. Depending on your allegiances, strikebreakers were known as loyal workers, volunteers, scabs or blacklegs.

Several hundred teenage boys from Sydney’s select private schools heeded the call, with many volunteering at Eveleigh Railway Workshops. Here, for over three weeks, they worked as cleaners and as ‘hands’ in the Machine and Erecting Shops; they cleaned locomotive engines in the Running Sheds; and worked as waiters on the ‘tucker brigade’ serving food to other volunteers. They were paid 9 shillings and 6 pence (approximately $44.78 in 2017)[14] a day. The first to join up were 160 boys from Sydney Grammar who arrived on 9 August 1917. They were soon joined by others from Newington and Shore.[15]

Thousands of women volunteered their services to help break the strike.[16] Among their number was Hazel Walker, studying teaching at Sydney University. She remembered the male engineering students ran the trains, while female students, including herself, worked in the railway refreshment rooms: ‘We as students thought it was great fun, doing something different.’ [17]

Strikebreakers from regional New South Wales were housed in camps at the Sydney Cricket Ground (nicknamed the ‘Scabs Collecting Ground’ by the strikers), Taronga Zoo and Dawes Point.

Scuffles, verbal abuse and some physical violence between strikers and strikebreakers were regular occurrences on the picket lines set up outside workplaces across the city, including the waterfront, the railway workshops at Eveleigh and tram depots. Arthur Emblem, a strikebreaker from Tamworth, later recalled ‘we had a lot of brushes with the wharf labourers’.[18]

There was one violent incident involving a strikebreaker from regional New South Wales and a striker that had wider social repercussions, exposing class warfare in Sydney a century ago. Reginald Wearne, a stock and station agent from Bingara (and the brother of Walter Wearne, MLA for Namoi) was in Sydney to break the strike. On 30 August 1917, Reginald Wearne shot dead a striking carter named Merv Flanagan during an altercation on Bridge Road, Camperdown. The murderer didn’t go to gaol; instead the victim’s brother and another striking carter named Harry Williams were tried and convicted of ‘using violence with intent to prevent Wearne from following his lawful occupation’.[19]

Impact

The strike officially ended when the Strike Defence Committee capitulated to the Railway Commissioners’ demands in mid-September 1917. But workers in maritime industries stayed out on principle, and it wasn’t until early October that industrial action and protest eventually wound up. At Sydney’s Eight-Hour Day procession in October 1917 the strongest turnout was from the ranks of the seamen, wharf labourers, and coal lumpers who ‘came in for a great deal of cheering at their display of solidarity’.[20]

Sacrifices were immense. It was estimated at the time that strikers lost around £1.8 million in wages (around $159.2 million today) and that the total economic loss to the community was between £3.4 million to £9 million (around $304 million and $805 million in today’s currency, based on the consumer price index).[21]

Ultimately, the strike failed. In its dying days and immediately afterwards, with no income coming in, destitute strikers and their families either did without, or relied on relief doled out by the Women’s Relief Fund at Sydney Trades Hall, and a fund set up by Sydney’s Lord Mayor. Women and children were hit especially hard.[22]

Legacies

The strike had long reaching impacts on conditions for working people, and the formation of political consciousness. Many railway and tramway employees never got their jobs back. Those who were rehired found their jobs had been downgraded. The strike highlighted the split in the labour movement between ‘rank and file’ trade union members and officials. More than 20 unions were deregistered, some never reinstated. In the years that followed, many strikers felt they had been victimised, which in turn created working lives riven with conflict.[23]

Bernie Johnston was a young boy living in Surry Hills in 1917. When interviewed 70 years later, Bernie remembered the strike as ‘a bitter thing because it divided the working class completely’. Likewise Bill White, a tram driver based at Rozelle Depot in the 1920s, recalled the strike and its aftermath as ‘a terrible time of victimisation and abuse and hatred, jingoism and patriotism…’[24]

[media]But the strike and its aftermath politicised a core group. One of these men, engine driver Ben Chifley, was a ‘Lilywhite’, meaning he stayed out for the duration of the strike. He went on to become Prime Minister from 1945-49. Labor stalwarts and former Eveleigh employees Joe Cahill and Eddie Ward both entered politics after their involvement in the strike. Cahill was a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly from 1925-59 and elected Premier in 1952, while Ward was a member of the federal House of Representatives for East Sydney 1932-60.

The nationwide strike lasted just six weeks, but its consequences endured for those involved. The event divided loyalties, shaped political consciousness, and created a highly politicised workforce from which a generation of politicians would later emerge, including a premier and a prime minister. Despite these legacies, the Great Strike of 1917 has not been widely remembered. Many considered the strike to be a defeat for the labour movement, and the action was subsequently overshadowed by the memory of war and the conscription debates, but the centenary anniversary of the strike in 2017 provided an opportunity to reassess this watershed moment in Australia’s history and to consider how its legacy resonates today.

A version of this essay was first published in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition 1917: The Great Strike at Carriageworks, in association with the City of Sydney, Sydney, 2017

References

Laila Ellmoos, Nina Miall, 1917: The Great Strike, Carriageworks in association with the City of Sydney, Sydney, 2017

Robert Bollard, In the shadow of Gallipoli: The hidden history of Australia in World War I, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2013

Robert Bollard, The Active Chorus: The mass strike of 1917 in eastern Australia. Unpublished PhD thesis, Victoria University, Melbourne, 2007 http://vuir.vu.edu.au/1472/1/bollard.pdf

Dan Coward, The impact of war on New South Wales: some aspects of social and political history 1914-1917. Unpublished PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, 1974 http://hdl.handle.net/1885/9267

Lucy Taksa, 'Merv Flanagan, Labour Martyr. The Mortuary Station Regent Street', in Irving T, & Cahill R. Radical Sydney: places, portraits and unruly episodes. UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 136-43

Lucy Taksa, ‘Defence Not Defiance. Social Protest and the NSW General Strike of 1917’, in Labour History, No. 60, May 1998, pp 16-33

Lucy Taksa, ‘All a Matter of Timing. Managerial Innovation and Workplace Culture in the NSW Railways and Tramways Department prior to 1921’, in Australian Historical Studies, No. 110, April 1998, pp 1-26

Lucy Taksa, ‘The 1917 Strike. A Case Study in Working Class Community Networks’, in Oral History Association of Australia Journal, No. 10, 1988, pp 22-38

Notes

[1] The New South Wales strike crisis, 1917: report prepared by direction of the Hon. the Minister for Labour and Industry by the Industrial Commissioner of the State, NSW Department of Labour and Industry, Sydney, 1918, p. 8a.

[2] ‘The cards’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 3 August 1917, p 8 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15739344.

[3] Lucy Taksa in Terry Irving & Rowan Cahill, Radical Sydney: places, portraits and unruly episodes, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010, pp 136-43

[4] NSW Legislative Assembly, Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Effects of the Workings of the System known as the Job and Time Cards System introduced into the Tramway and Railway Workshops of the Railway Commissioners in the State of New South Wales : together with minutes of evidence and exhibits. W A Gullick, Government Printer, Sydney, 1918

[5] Year book, Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 1918

[6] NSW Council on the Ageing and Oral History Association of Australia NSW Branch, Gwen Green interviewed by Brenda Factor in the NSW Bicentennial oral history collection, NSW Bicentennial Oral History Project, 1987 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-216224664

[7] Terry Irving & Rowan Cahill, Radical Sydney: places, portraits and unruly episodes, UNSW Press, Sydney, 2010 pp 144-50

[8] Sydney Mail 15 August 1917, p 14 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page16903651.

[9] 'Hooting loyalists', The Maitland Weekly Mercury, 8 September 1917, p 10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article128050006.

[10] ‘Strikers’ Procession’, The Bathurst Times 5 September 1917, p 2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article111557034

[11] Sydney Mail, 15 August 1917, p 10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article160628739

[12] Parliament and the war, To our last shilling: the Australian Parliament and World War I, https://tols.peo.gov.au/parliament-and-the-war/unlawful-associations-act-1916, viewed 21 Mar 2018; Unlawful Associations Act 1916, Federal Register of Legislation, https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C1916A00041, viewed 21 Mar 2018

[13] Robert Bollard, In the shadow of Gallipoli: The hidden history of Australia in World War I, NewSouth Publishing, Sydney, 2013

[14] Pre-Decimal Inflation Calculator, Reserve Bank of Australia website https://www.rba.gov.au/calculator/annualPreDecimal.html viewed 10 April 2018

[15] The Sydneian, September 1917, pp 21, 26-28 http://www.sydgram.nsw.edu.au/files/the-sydneian/1910-1919/233_The_Sydneian_SEP_1917.pdf; 'Volunteers at Eveleigh Yards', The Sun, 13 August 1917, p 2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article221400119[16] ’Topical Talk’, The Australian Worker, 13 September 1917, p 10 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article145811546 ; 'Loyal Service Bureau', The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 September 1917, p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15758313

[17] Hazel Walker interviewed by Judy Wing in the NSW Bicentennial oral history collection, NSW Council on the Ageing and Oral History Association of Australia NSW Branch, 1987, National Library of Australia, ORAL TRC 2301/165, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-216331484

[18] Arthur Emblem interviewed by Gwen McGregor in the NSW Bicentennial oral history collection, NSW Council on the Ageing and Oral History Association of Australia NSW Branch, 1988, National Library of Australia, ORAL TRC 2301/186, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-216354019

[19] Richmond River Herald, 4 September 1917, p 3 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article125927675.

[20] ‘Eight-hour day in Sydney’, The Australian Worker, 4 October 1917, p 6 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article145807466

[21] Year book, Australia, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Canberra, Australia, 1918

[22] ‘Hunger and suffering’, Sunday Times, 14 October 1917, p 15 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122797764 ; Railway Strike, 1917: report, balance sheet and statement of receipts and disbursements, defence and relief fund, to December 1917, Labor Council of New South Wales, Sydney, 1918

[23] W Jurkiewicz, Conspiracy aspects of the 1917 strike, Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) thesis, University of Wollongong, 1977 http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/885

[24] Bernie Johnston interviewed by Catherine Johnson in the NSW Bicentennial oral history collection, NSW Council on the Ageing and Oral History Association of Australia NSW Branch, 1987, National Library of Australia, ORAL TRC 2301/115, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-216268371; Richard Raxworthy, 'Australians at Work', interviews with retired tram and bus workers from Sydney and Newcastle, Bill White interviewed by Richard Raxworthy in the Australians at Work oral history collection, Marrickville, NSW 1982. Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, MLOH 2, http://archival.sl.nsw.gov.au/Details/archive/110055968