The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Māori

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Māori

Non-Indigenous written history claims there was no contact between Māori and Koori. [1] Despite this, Indigenous lore in Australia tells of contact between the two. In the early days of the colony, trans-Tasman travel was fluid between Sydney and New Zealand for Māori and non-Indigenous people alike.

An eighteenth-century [media]map by Daniel Djurberg shows an alternative name for New Holland as 'Ulimaroa'. This was widely believed to be a Māori word for Australia; however there is no L in the Māori alphabet. This may mean it was a Polynesian word, perhaps Hawaiian or Samoan, however it does not explain how the name came into Djurberg's possession.

From 1788 to 1840 the colony of New South Wales included New Zealand. The head of state was the monarch, represented by the governor of New South Wales. British sovereignty over New Zealand was not established until 1840, when the Treaty of Waitangi recognised that New Zealand had been an independent territory until then. The Declaration of Independence signed in 1835 by a number of Māori chiefs and formally recognised by the British government indicated that British sovereignty did not extend to New Zealand. This meant the British in Sydney had no option than to deal with Māori, who were still in control of their own land.

The history of Māori in Sydney and the critical role they played in the success of the town has been minimised by historians. Indeed most Sydneysiders today think that Māori contact, enterprise and migration is a relatively new phenomenon.

Early Māori visitors

During 1788–1840, [media]Māori were often described as 'New Zealanders' [2] – the white inhabitants of Sydney called themselves 'British'. Māori were a familiar and common sight in Sydney.

The Polynesian protégés of Parson Marsden became a familiar sight in the streets of the little colonial town. The residents of Parramatta were so accustomed to their presence in subsequent years that Māoris occasioned considerably less comment than would a party of them today. [3]

The early European inhabitants of Sydney Town had to deal with Māori, however fearsome, tattooed, brown-skinned and different, if they wished their colony to survive.

The first written history of Māori in Poihakena (Port Jackson) dates back to1793 when Lieutenant-Governor King had Tuki Tahua and Ngahuruhuru (also known as Huru) kidnapped from the Bay of Islands. They were taken to Norfolk Island to teach female convicts how to weave flax into garments but this was not men's work. In marked contrast to their earlier criminal treatment, they were returned to the Bay of Islands after a stay in Sydney as King's guests. [4]

Prior to their return, Tuki drew a map for King of the far north of his island, but omitted the mighty Hokianga harbour. Tuki described to King the 'pine trees of an immense size' that grew there. These trees would become the basis for the New South Wales timber and flax trade. This trade facilitated hundreds of Māori coming to Sydney. [5]

King's careful courting of Tuki meant he now had knowledge of rich resources, all of which would eventually contribute to the colony. King sent Tuki back with gifts, which had been meticulously and deliberately chosen. These included wheat, maize, peas, sows and boars, as well as hand axes, carpenters' tools, scissors, razors, spades and seeds. King was deliberately introducing items for which a demand would grow. [6]

Te Pahi and his family

In 1805, [media]largely as a result of Tuki and Huru's accounts of Sydney, Te Pahi, a chief of Te Hikutu (north-west of Bay of Islands), travelled to Sydney with his four sons. They arrived on the HMS Buffalo via Norfolk Island and stayed for nearly three months at Government House with King. The visit was recorded in the Sydney Gazette. [7]

During this time, Te Pahi met with John Macarthur, spending three days at Parramatta where the process of working wool and making cloth was explained. Te Pahi also spent time at the Criminal Court where he was exceedingly critical of the death sentence given to three convicts who had been accused of stealing pork. Te Pahi attempted to have them transported to New Zealand, where stealing food was not a crime. [8]

Te Pahi left Sydney on 24 February 1806 after being given a silver medal inscribed:

Presented by Governor King to Tip-a-he during his visit to Port Jackson in January 1806. [9]

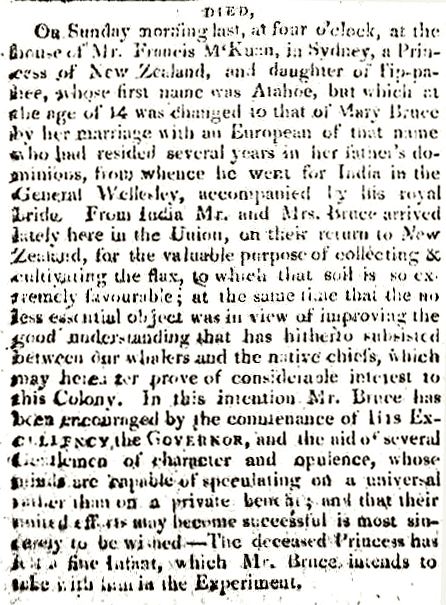

On Saturday 3 March 1810 [media]an article appeared in the Sydney Gazette referring to the death of a 'Mary Bruce' at the house of Mr Francis McKuen. She was described as

a Princess of New Zealand, and daughter of Tip-pa-hee, whose first name was Atahoe, but at the age of 14 changed her name to that of Mary Bruce by her marriage with an European of that name. [10]

Te Atahoe was the daughter of Te Pahi. She married George Bruce, a former convict from Sydney who, depending on which account is read, variously escaped, fled or went to New Zealand. By one account, he nursed Te Pahi, who had fallen ill during the trip back from Sydney. The less flattering accounts of Bruce may have arisen from missionary morals, as many frowned upon white men who married Māori, and living as a 'Pakeha-Māori', complete with ta moko (facial tattoos), made it even worse. Such men were commonplace in the colony, often visiting with their Māori wives and children.

Te Atahoe and Bruce arrived in the colony via India in January 1810. [11] They had been kidnapped by a Captain Dalrymple and taken to Malaysia and India. In late 1808, Te Pahi and three of his sons travelled to Sydney to meet with Governor Bligh about his daughter's kidnap. Bruce and Te Atahoe missed her father and brothers, who had been unable to see Bligh.

Her death came one month after giving birth to her daughter. [12] She was 18 years old.

Te Atahoe was buried at the Old Sydney Burial Ground which is now the site of Sydney Town Hall. When construction began on the Town Hall, she was exhumed and taken to Haslams Creek, which became Rookwood Necropolis. [13]

Te Pahi was falsely accused of orchestrating a massacre on the ship the Boyd, at the Bay of Islands. It is probable that this massacre was conducted by a neighbouring tribe keen to monopolise the trade with Europeans. The repercussions were considerable and many chiefs, including Ruatara (Duaerra), Hongi Hika and Korokoro, visited Poihakena over the next few years. The most significant visit was that of Ruatara.

Ruatara

Ruatara (Te Hikutu) travelled to Sydney and beyond many times, first in 1805. He was brought to Parramatta by Samuel Marsden and when he returned to New Zealand he laid the foundations for Marsden's proselytising.

Samuel Marsden, known as the flogging parson and a member of the London Missionary Society (LMS), was the parson at St John's church in Parramatta. He had travelled to England with the view of setting up a mission in New Zealand. He did not only have the 'spiritual welfare' of Māori in mind – there is no doubt he also had one eye on the resources of flax, kauri and gum so plentiful in the Hokianga.

In 1814, Marsden sent an invitation to Ruatara (Duaerra), Hongi Hika and Korokoro to visit Sydney. John Liddiard Nicholas wrote that Marsden had specifically brought these chiefs across in his own brig, the Active, because he wanted to 'excite a spirit of trade amongst the New Zealanders'. This would be maintained from Port Jackson to 'create artificial wants to which they had never become accustomed,' leading to a dependency on the missionaries that would allow them to preach their evangelical message. Ruatara had been warned that accepting this would lead to many Europeans coming to New Zealand. [14]

Ruatara, Korokoro and Hongi Hika returned to New Zealand with a vision. Ruatara wanted to build a European town at Rangihoua in the Bay of Islands, which was where Marsden eventually started his mission. Korokoro even took a new name 'Kawana Makoare' (Governor Macquarie).[15]

The Active [media]had a regular crew of Māori who travelled between the Bay of Islands and Sydney. For the most part, Māori were treated well, however, the Sydney Gazette on 3 December 1829 reported

a number of New Zealanders are at present in town, and all who notice them as they pass along the streets can bear testimony to their order, peaceable conduct. We cannot, however, say as much for the behaviour of those who boast superior civilization. On several occasions, the poor Islanders have been most wantonly assailed in the streets with stones and other missiles.

The paper stressed the lucrative trade between the countries and how it could be jeopardised by retribution for this incident. [16]

Trade and commerce

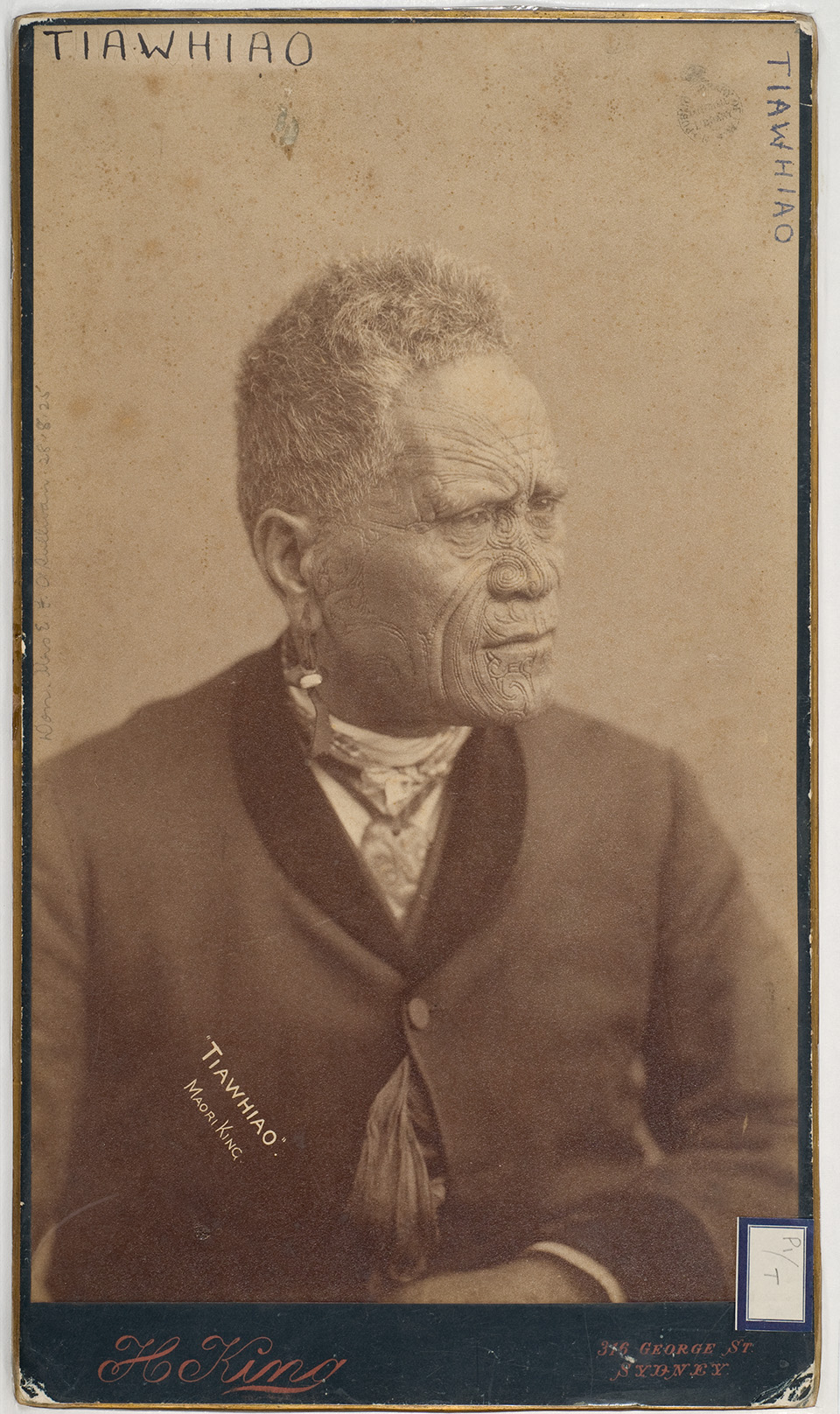

Māori [media]chiefs travelled regularly to Sydney to establish trade ties. They had become shrewd businessmen and realised the prestige they could gain by fostering economic ties with Sydney. In return, the businessmen of Sydney were fully aware of the need to cultivate Māori in order for the colony to progress. Māori learned English and many British sailors and traders living in Sydney spoke Māori. New Zealand historians call this period 'the Māori domination' where Māori culture was as dominant as British culture. [17] The Sydney Gazette during this period has many references to shipping movements between New Zealand and Sydney, as well as to Māori in Sydney.

Patuone (Ngati Hou) came to Sydney to negotiate for vessels to sail to Hokianga for spars. He returned with Captain Deloitte who purchased Te Horeke on the south of the Hokianga. Te Horeke became the major centre of timber trade in the colony. As a result, in 1828 the timber wharf in George Street was opened, specialising in spars from Te Horeke. In 1814 Tuai (Te Hikutu) travelled to Sydney to negotiate a timber contract with Blaxcell and Co. The timber from the Hokianga was cut under direction of the chiefs by Māori labour. Trade, however was not all one-sided. Parramatta cloth, a mix of cotton and wool made by the convicts at Parramatta was popular among Māori purchasers and greatly in demand. [18] Weapons, especially guns, were a popular commodity.

Marsden established [media]a seminary for Māori chiefs' sons at Parramatta in 1819. It was not successful, and the spot where the seminary stood is now the reserve 'Rangihoua' in Parramatta. By 1827, Marsden was contemplating creating a permanent settlement at Lake Macquarie for Māori chiefs and their families. His motives were not entirely altruistic – the lucrative flax and wood trade was worth approximately £26,000 by 1831. [19]

By the 1820s Māori were so commonplace in Sydney that an almost contemptuous attitude had arisen. A Waikato chief who travelled to Sydney to meet with Governor Darling sat on deck for two days waiting for an audience, not having been acknowledged by Darling, or sent for. This was an ominous portent of what was to come.

The peak years of trade between Māori and Sydney were the 1830s when 60 to 75 vessels left Sydney for New Zealand. The value of Māori exports to Sydney and Van Diemen's Land by 1839 had reached £83,000. [20]

Weapons of war

The chiefs, however, being shrewd businessmen and even shrewder strategists, saw Sydney as a place to acquire weapons for war between their tribes and other Europeans in New Zealand. There were three known attempts to bring Māori before the New South Wales Supreme Court in Sydney for crimes against Europeans. The last of these cases, in 1839, was aborted when the accused was freed by other Māori in Sydney. Culturally, only Mokai, or slaves, were allowed to be treated in this manner. [21]

Even the famed Ngati Toa chief, Te Rauparaha, composer of the seminal haka 'Ka Mate', visited Sydney. He resided at Parramatta with Marsden and was introduced to Darling. The reason for his visit was to procure a European vessel to take his war party to the South Island, with devastating results. It was during this war that 'Ka Mate' was performed and this is one of the reasons why, out of respect for the Ngai Tahu, it is not performed by the All Blacks today, when they play in the South Island.

Separation of New Zealand from New South Wales

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was formulated as a way of removing sovereignty from Māori to the Crown in order to obtain land. Governor Bourke had little regard for Māori and even less regard for the British Resident in New Zealand, James Busby. Busby attempted to consult with the chiefs and to create a form of Māori government, including their own flag (of which three prototypes were made in Sydney and shipped to New Zealand for the occasion). Part of his rationale was that New Zealand-built ships were being refused registration in New South Wales as New Zealand was not a British colony. Once enacted and a flag chosen, vessels flying the Māori flag would be able to freely enter Port Jackson.

Bourke succeeded in conveying the view to Britain that lawlessness reigned in New Zealand and his representations along with those of Marsden, Busby, Browne and other Sydney merchants allowed Britain to make a decision in relation to New Zealand. William Hobson was despatched from Britain to oversee the task of a 'treaty'. He arrived in Sydney and made legal arrangements with Governor Gipps. On 14 February 1840, Gipps held a tea-party for the Māori chiefs living in Sydney. Seven of the 10 invited guests came. He gave them 10 sovereigns each to sign the treaty the next day. None returned, upon advice of a Sydney merchant, John Jones, who could see the manipulation and theft of Māori land by a Sydney land consortium. Gipps's treaty asked the chiefs to cede absolute authority to the Crown. [22]

Hobson's treaty did not cede absolute authority to the Crown. However considerable debate arose and Te Taonui challenged;

We are glad to see the Governor come and be a Governor to the Pakeha, as for us we want no Governor, we will be our own Governor. How do the Pakeha behave to the Black Fellows at Port Jackson? They treat them like dogs…… [23]

The treaty, however, was signed.

Sydney's part in the New Zealand Land Wars

By 1845, in response to the confiscation and sale of Māori land to Europeans, the New Zealand Land Wars (formerly called the Māori Wars) had commenced, in which Sydney had considerable involvement. Two gunboats, as well as munitions, were made in Sydney for dispatch to the war against Māori who wished to remain on and claim their land.

Men from Sydney were encouraged to fight the Māori, with the largest contingents from Sydney fighting in the Waikato War of 1863–64. Almost 2,500 men volunteered to fight, having been offered the land of Māori they defeated. [24] A memorial to the men killed in the Land Wars can be found at the entrance to Burwood Park.

At the conclusion of the war almost 16,000 square kilometres of land was confiscated by the Crown, under the New Zealand Settlements Act and given or sold to Pakeha. The halcyon days of Māori–Sydney trade were almost at an end.

[media]After the wars, there is little reference to Māori in historical writings. The economic force that characterised Māori relationships with Sydney had been decimated by the Land Wars and the subsequent confiscation of Māori land and assets. It appears that few Māori visited Sydney and even fewer were residents. Paul Hamer surmised that

perhaps the novelty of their presence had worn off or possibly their numbers in Australia were much fewer after the turmoil in their homeland. [25]

The 1856 New South Wales Census stated

As the Natives of New Zealand did not exceed 40–50 souls they were included under the general heading of Australia and New Zealand. [26]

Twentieth century migration

The Pacific Island Labour Act 1901 allowed Pacific Islanders into Australia but specifically excluded Māori. [27]

Surprisingly, Māori had the vote in Australia from 1902. The Commonwealth Franchise Bill 1902 stated 'No Aboriginal native of Australia, Africa or the islands of the Pacific except New Zealand shall be entitled to have his name placed upon the electoral roll…' [28]

Yet in 1903 customs officers denied entry to three Māori who arrived with a circus. By 1905, after discussion with New Zealand authorities, Māori were admitted on the same basis as Pakeha. However between 1902 and 1920, Māori were still a category to whom an immigration 'dictation test' could be administered. [29]

On 29 April 1948, the New Zealand paper The Dominion reported Arthur Calwell, the then Minister for Immigration, asserting that Māori could be excluded from Australia under the White Australia Policy.

The Māori [media]population, however small, remained a presence in Sydney. In 1909 and again in 1910 a Māori village, Te Arohanui, was erected in Clontarf by Maggie Papakura (Te Arawa) (Guide Maggie). [30] The Telegraph reported that once again Sydney was graced with Miss Papakura's presence. The show and village operated from December 1909 to April 1910 with steamers running from Fort Macquarie to Clontarf. The show then toured to Adelaide and London. [31]

From this time on the limited writings on Māori in Sydney are dominated by 'entertainers'. It appears that within a limited time, Māori had gone from equal status in Sydney society to mere curiosities who provided entertainment value. In 1913, cadets from Duntroon parodied Māori culture by dressing in blackface and Māori costume. [32] Yet, ever the entrepreneurs, Māori began to dominate the Sydney music scene.

Entertainment years

During the 1950s and 1960s, Sydney was [media]home to some of the very best Māori bands. Some of the bands playing at venues such as the Chevron and Whiskey a Go Go were the Māori Troubadours, Māori Volcanics, Māori Hi-Five and Quin Tikis.

The Māori Troubadours were formed in 1953 when Johnny Nicol met Prince Tui Teka and Mat Tenana at a gym in Redfern. Tui Teka had moved to Sydney in the early 1950s and returned to New Zealand in the 1980s where he had numerous hits. Other legendary Māori performers included Noel Kingi, Gugi Waaka and Peter Paki.

By 1959, the Māori Hi-Five and Māori Troubadours were regulars on Six O'Clock Rock. [33]

In 1962, arguably the most famous Māori entertainer, Ricky May, arrived in Sydney. He was to make his home here until his death in 1988. By the late 1960s Ricky was hosting his own television show on Channel 10 called 'Ten on the Town'. [34] In the 1970s, Ricky composed the Newtown Jets theme song. The song has welcomed the Jets onto the field at every Henson Park match since then. [35]

Māori [media]entertainers did not just sing. In 1959, transgender icon and activist Carmen arrived in Sydney. She was one of the iconic members of the drag troupe Les Girls at Kings Cross, joining in 1963. In 2003 she was inducted into the Variety Hall of Fame. Domiciled in Surry Hills, Carmen was given a motorised scooter by Sydney residents for her 70th birthday. [36] After her death at St Vincent's Hospital in December 2011, she was farewelled by a huge and diverse crowd at the Māori Anglican church of Te Wairua Tapu in Redfern.

Cultural ties

Māori[media]cultural groups were a feature of Sydney. Continuing from Maggie Papakura's Māori village at Clontarf, performances and hangi were often used to showcase Māori culture. In 1958, Miss Australia was farewelled by 'Māori Dancers' at Mascot. [37] In 1960, TEAL-QANTAS House featured a lavish display of Māori culture, to promote New Zealand. [38] Part of this promotion showed a 'Māori Male musical group in Native Costume' at Mascot Airport, however the caption claimed they had just arrived from New Zealand on a TEAL (Air New Zealand) aircraft! This picture portrayed Māori as 'noble savages' who ordinarily dressed in 'native' costume.

The [media]gimmick of representing New Zealand solely through Māori culture continued. New Zealand Day (now called Waitangi Day) was regularly celebrated with Māori dancing (Kapa Haka) and hangi. [39]

Kapa Haka

For Māori living in Sydney, it was important that their culture be maintained and passed on, not just to other Māori. In the early 1970s a Māori Kapa Haka group at Pendle Hill, called Poihakena, had a number of Australians in the group. The founder of this group, Gwen Nikora, was married to an Australian. Poihakena, under the name Te Aroha, went on to perform at the inaugural Carnivale at Sydney Town Hall in 1978.

By 1979, there were enough Kapa Haka groups in Sydney to stage the first Māori Festival of Sydney Cultural Competitions. On 5 May 1979, these were held at Paddington Town Hall. Te Aroha performed again, this time as a children's group, made up of children of Māori descent, who were either born or had spent a substantial part of their lives in Sydney. The tutor of this group, Matiu Campbell, wrote a song for the event called 'Ahitereria' (Australia) which described the children knowing where they came from (New Zealand) but being proud to be Australian. Criticised by some recent members of the Sydney Māoricommunity for placing children alongside adults in Kapa Haka competitions, Mat Campbell remained steadfast in promoting and instilling a Māori Australian identity, not only in those children, but the Māori-Australian children who had gone before them. It was at this event that he called the children 'Ngati Kanguru' or the 'Family Kangaroo'. The judges for this competition included Whetu Tirakatene-Sullivan, a Member of the New Zealand Parliament (who incidentally completed postgraduate studies at the ANU in the 1960s) and Sir Kingi M Ihaka, Sydney's first Māori Anglican minister.

Te Wairua Tapu, Rookwood Urupa, Te Puna Roimata

During the 1970s a body was set up to deal with Māori cultural and social matters in Sydney. This body was called the Poihakena Society and was made up of elders in the community.

The majority of Māori who died in Sydney had their bodies returned to New Zealand tribal lands to be buried with their families. This was of concern to many of the elders in Sydney who realised there was a need for a Māori cemetery (urupa) in Sydney for those who could not afford to be sent 'home' or who wanted to stay. Lobbying by the elders resulted in a dedicated urupa at Rookwood Cemetery, not far from where Te Atahoe (Mary Bruce) is buried. Matiu Campbell, the tutor of the Te Aroha group, was one of the first elders to be buried there. His ancestor, Frederick Maning was a 'Pakeha Māori' married to Moengaroa, a princess, and regularly travelled between Sydney and the Hokianga in the nineteenth century for trade.

Māori in Rugby League

In 1908 Sydney's fledgling Rugby League competition was finding it hard to be economically viable. The founder of the League, James J Giltinan engaged a rugby league team comprised completely of Māori players and captained by the well known Albert Opai Asher – who had last been seen in Sydney with the New Zealand team in 1903, to play a number of test matches in Sydney. The fame of Asher assured a successful ticket take and drew over 30,000 spectators to the Sydney Showground at Moore Park.

Upon arrival in Sydney the All-Māori team were met by 'drags' (horse-drawn coaches) and taken along Sussex Street to St James Hall in Phillip Street where they were given a civic reception.

The All-Māori match proved to be the New South Wales Rugby League's greatest triumph to date. The team returned in 1909 for further matches when Rugby League was once again on the brink of financial ruin, but after the first two matches, with a combined gate of 50,000 people, the league was saved. Unfortunately, the Māori team were treated abysmally by Giltinan who claimed there had been a 'broken turnstile' at the Sydney Showground, as well as a court injunction and deduction for hiring the ground (even though the League held the lease over the Sydney Showground). The Māori team received no payment.

The Māori team along with sympathetic footballers attempted to hold a benefit match to enable them to clear their debts and earn enough money to return home. Although it was billed as a benefit match, the League warned players they were not to participate:

no league player was permitted to take part in an unsanctioned game, and any who did would 'go up' for life. [40]

Today, every Sydney team in the NRL competition has at least one Māori player and the Auckland Warriors field a team in the competition.

Māori life in Sydney

Māori are everywhere, socially and economically integrated into Sydney life. Māori enjoy a unique position in Australia, having almost unrestricted access to the country rather than arriving on a specific migration programme. The Māori population in the 2001 Census placed the Māori population in Sydney at 20,357, with the largest groups living in the St George-Sutherland Shire (3,307) followed by Blacktown (2,132) and Central Western Sydney (2,095). [41]

The entrepreneurial nature of Māori has seen representation in all walks of life. If you had a pool built in Sydney in the 1970s, chances are it was built by Ron Haira, the proprietor of Polynesian Pools. Sydneysiders may have been taught by Elizabeth Ngawaiata Assill at primary school or caught a bus driven by Ken MacKenzie or Bill Ngawaka. Today, Te Kura Akorangi O Māori O New South Wales (The Māori School of Learning NSW) is situated at Lidcombe, teaching Māori and non-Māori tikanga and reo (culture and language). [42] The Māori Business Network lists Māori-owned Sydney businesses including everything from caterers to graphic designers to fraud investigators. [43] Māori radio airs on Koori Radio with Nellie and Koro Riki's sounds on 'Te Reo Irirangi O Poihakena' or Percy Bishop's Tangata Whenua show. [44]

Māori played a major role in establishing Sydney and they continue to enrich its cultural and economic life.

References

J Belich, Making peoples: A history of New Zealanders: from Polynesian settlement to the end of the nineteenth century, Penguin Books, Auckland New Zealand, 1996

T Bentley, Pakeha Māori: the extraordinary story of the Europeans who lived as Maori in early New Zealand, Penguin Books, Auckland New Zealand, 1999

P Diamond, Makereti – taking Māori to the world, Random House, Auckland New Zealand, 2007

P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington New Zealand, 2007

J Lee, Hokianga, Reed Books, Auckland New Zealand, 2006

Makereti, The old-time Māori, New Women's Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1986

FE Maning, Old New Zealand: A tale of the good old times by a Pakeha Māori, Wilson & Horton, Auckland New Zealand, 1970, first published 1863

H Petrie, Chiefs of industry, Māori tribal enterprise in early colonial New Zealand, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 2006

Notes

[1] P Bergin, 'Māori Migration and Cultural Identity', DPhil thesis, University of Oxford, 1998; P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007

[2] Sydney Gazette 1803–1820; E Ramsden, Marsden and the missions: Prelude to Waitangi, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1936

[3] E Ramsden, Marsden and the missions: Prelude to Waitangi, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1936

[4] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987; JMR Owens, 'New Zealand Before Annexation', in WH Oliver and BR Williams (eds) Oxford History of New Zealand, Oxford University Press, Wellington, 1981

[5] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[6] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[7] Sydney Gazette, 8 December 1805

[8] Sydney Gazette, 8 December 1805; R McNab, From Tasman to Marsden: A history of northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818, J Wilkie and Co, Dunedin New Zealand, 1914

[9] R McNab, From Tasman to Marsden: A history of northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818, J Wilkie and Co, Dunedin New Zealand, 1914

[10] Sydney Gazette, 3 March 1810; New South Wales Births Deaths and Marriages, Mary Bruce, d 28 February 1810, V18102476 2A/1810

[11] A Salmond, Between Worlds: early exchanges between Māori and Europeans, 1773–1815, Penguin Books, Auckland New Zealand, 1997

[12] '1800-09', Tai Awatea Knowledge Net, Te Papa website, http://tpo.tepapa.govt.nz, viewed 16 February 2009; R McNab, From Tasman to Marsden: A history of northern New Zealand from 1642 to 1818, J Wilkie and Co, Dunedin New Zealand, 1914

[13] 'Old Burial Ground Sydney – Inventory of Burials, 1792–1820', City of Sydney website, www.cityofSydney.nsw.gov.au/aboutsydney/documents/hisoty/references_burials_inventory.pdf, viewed 15 February 2009

[14] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[15] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[16] Sydney Gazette, 3 December 1829

[17] K Sinclair, 'Australian Colony' in K Sinclair, A history of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland, New Zealand, 2000

[18] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[19] K Sinclair, 'Australian Colony' in K Sinclair, A history of New Zealand, Penguin, Auckland, New Zealand, 2000

[20] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[21] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[22] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987

[23] J Binney, 'Tuki's Universe' in K Sinclair (ed), Tasman Relations: New Zealand and Australia 1788–1988, Auckland University Press, Auckland New Zealand, 1987, F Welsh, Great southern land: a new history of Australia, Allen Lane, London UK, 2004

[24] L Barton, Australians in the Waikato war, 1863–1864, Library of Australian History, Sydney, 1979

[25] P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007, p 12

[26] P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007, p 12

[27] P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007, p 12 Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901, available online at National Archives of Australia, Documenting a Democracy website, http://www.foundingdocs.gov.au/resources/transcripts/cth4i_doc_1901.pdf, viewed 13 May 2010

[28] F Welsh, Great Southern Land, A new history of Australia, Allen Lane, London, 2004

[29] P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007, p 12

[30] P Diamond, Makereti: taking Māori to the world, Random House, Auckland New Zealand, 2007; Photographs in State Library of New South Wales picture collection.

[31] Telegraph, 26 December 1910, p 7

[32] Group portrait of New Zealand staff cadets at Royal Military College Duntroon, 1913, Australian War Memorial, P02029.013

[33] National Archives of Australia, holding Series SP1426/4 Six O'Clock Rock 1959–1960

[34] 'Ricky May', http://www.sergent.com.au/rickymay.html, viewed 2 March 2009

[35] Newtown Jets website, 'Newtown Jets Team Song', http://www.newtownjets.com.au/NewtownSong.php viewed 2 March 2009

[36] 'Carmen', TimeOut website, http://www.timeoutsydney.com.au/thebridge/colourfulsydneyidentity/carmen.aspx, viewed 2 March 2009

[37] Photographs by Jack Hickson, 10 March 1958, Australian Photographic Agency collection, State Library of NSW

[38] Photographs by Ken Redshaw, 18 January 1960, Australian Photographic Agency collection, State Library of NSW

[39] Photographs by Barry Newberry, Australian Photographic Agency collection, State Library of NSW

[40] S Fagan, Pioneers of Rugby League, RL1908 Australia, 2007

[41] P Hamer, Māori in Australia, Te Puni Kokiri, Wellington, New Zealand, 2007

[42] Te Kura Akōranga Māori o NSW website, www.akomaori.com, viewed 13 May 2010

[43] Māori Business Network website, www.maoribusinessnetwork.com.au, viewed 13 May 2010

[44] Gadigal Information Service website, Koori Radio page, HYPERLINK "http://www.gadigal.org.au/KooriRadio/About Us.aspx"www.gadigal.org.au/KooriRadio/About Us.aspx, viewed 13 May 2010

.