The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Biffin, Harriett Eliza

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Biffin, Harriett Eliza

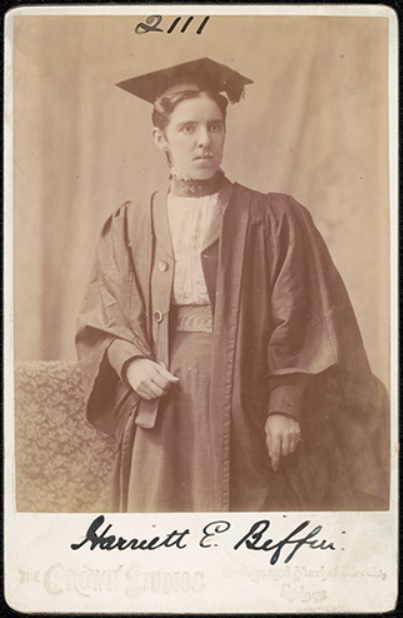

[media]Harriett Biffin was a pioneer Sydney woman doctor. One of the second group of women to graduate in medicine at the University of Sydney in 1898, she was the first to establish a women’s joint medical practice in Sydney and a suburban general medical practice, and founded both the Medical Women’s Society of New South Wales and the Rachel Forster Hospital with Dr Lucy Edith Gullett.

Early life

Harriett Eliza Biffin was born in Sydney on 24 December 1866, the only surviving child of Eliza Humfrey, a midwife and Theosophist, and James Biffin, a commercial traveller and orchardist. The Chase and Eastern Roads in Turramurra bounded the family’s 23-acre property and orchard.[1] She appears to have been named after her mother Eliza and grandmother Harriett Ann Shirley.

Biffin was educated privately before attending Sydney Technical College, where she studied chemistry, and was receiving tuition from Misses JF Russell and Ellis when she passed the university matriculation examinations at her third attempt in 1887.[2]

The University of Sydney

[media]Biffin was admitted as a member of the University in March 1887 and began Arts the following year. She was inspired to enter medicine by her mother, who was described by her great nephew as ‘a very intelligent and well-read person of independent mind’[3] and enrolled in the Faculty of Medicine in 1889.

The financial cost of studying medicine in Australia at this time was extremely high, and failure in professional examinations in medicine at the University of Sydney in the 1880s and 1890s was not uncommon, particularly for women students[4] who were not taught science at private schools for ‘ladies’ in Sydney. Biffin failed medicine five times, four of these during the fourth year, which she repeated from 1891-95. Family recollections reveal the impact of family responsibilities on her success in examinations, and at one point she ceased study to help operate the family orchard after her father became bankrupt. Family memoirs also state that the lecturer in anatomy in particular ‘would not have a woman in his class.’[5]

Despite these ongoing hardships, Biffin was active in University life where she was elected a committee member of the Ladies’ Tennis Club, and supported the University Musical Society.

[media]In the face of trying financial and personal circumstances over a period of ten years, her determination to graduate was remarkable. In 1898 Biffin graduated Bachelor of Medicine and Master of Surgery (MB ChM), with other women medical students Ada Caroline Affleck, Julia Carlile Thomas and Alice Sarah Newton.

Women refused hospital residencies in Sydney

After enduring the protracted and difficult curriculum, Sydney’s women medical students suffered galling injustice from their hometown hospitals. As graduates they needed and desired the opportunities of hospital experience, but a misogynist medical culture meant its public hospitals refused women medical graduates residencies until 1909.

Biffin, Affleck and another former University of Sydney medical student Ellen Maud Wood were all rejected by Sydney Hospital as resident medical officers in January 1898, and had no choice but to seek clinical placements elsewhere. In Australia at this time, there were not a lot of options. Women travelled to Melbourne, Brisbane or Adelaide to gain the necessary hospital experience, but their chances of gaining residencies in these capital cities were often equally poor because of competition from male graduates and entrenched prejudice.

Registration with the New South Wales Medical Board and resident medical officer at Adelaide Hospital

Biffin registered with the New South Wales Medical Board on 9 February 1898 with certificate number 2111, on the same day as Ada Affleck.[6]

Accustomed to rejection, Biffin approached a staggering number of Sydney doctors for references to support her application to Adelaide Hospital. Her exhaustive list included testimonials from doctors and other professors from the university and Prince Alfred Hospital. Adelaide Hospital accepted her application.

In 1898 Biffin travelled to Adelaide Hospital to take up a 12-month joint appointment as resident medical officer with Dr Ellen Maud Wood, the first female resident medical officers at the Adelaide Hospital and the first women to be appointed to the hospital’s medical staff.

Despite her glowing Sydney testimonials, Biffin was still paid less than Dr Kinmont, the male doctor she was replacing. Biffin and Wood each received a salary for the first three months at £100 per annum, and afterwards at £120 which included residence, rations, fuel and lights. By contrast, Dr Kinmont’s salary had been £250 per annum.

Private practice

Biffin and Wood returned to Sydney in 1899 to establish a private practice together at 197 Elizabeth Street in the medical precinct of the city. In view of their limited medical experience, and undeveloped Sydney networks for referral, this would have been an expensive and risky venture. They are separately listed at this address in the register of the New South Wales Medical Board from 1900 until 1907.

By 1907 there were close to 40 women doctors registered in New South Wales with only a handful practicing in Sydney.[7] Some researchers have claimed that Biffin and Wood’s Elizabeth Street practice did not succeed,[8] however their seven-year partnership suggests it must have thrived at least in the short-term whilst they juggled other medical roles. Biffin continued at the practice in Elizabeth Street until 1909, and then relocated to 141 Elizabeth Street Sydney where she remained until 1915.[9] Wood meanwhile moved to Beecroft and then to rural New South Wales and Queensland, continuing to practice until her death in 1935.

Medical officer to the Women’s Australian Natives’ Association

To support her private practice, in 1903 Biffin took on the role of medical officer to women at the first Sydney branch of the Women’s Australian Natives’ Association. The association was established to provide all the benefits of a Friendly Society to Sydney women of humble means including girls in factories, showrooms and offices. It aimed:

To assist the Women of Australia in every walk of life by promoting and advancing the interests of the working and professional women of Australia, more particularly those who have entered the Medical Profession.[10]

Her appointment was short-lived, with the British Medical Association (BMA) informing her that it considered the Women’s Australian Natives’ Association as ‘inimical to the medical profession’, part of an ongoing dispute between the BMA and groups registered under the Friendly Societies’ Act.[11] This would have been a deep disappointment to Biffin who was trying to establish her name, networks, financial security, and a professional career in Sydney. She resigned as requested, but despite having been an active member of the New South Wales branch of the BMA since 1901, never again renewed her membership.[12]

In these early years of her career, Biffin continued to be civically engaged, and served as an elected council member of the Women’s Branch of the British Empire League in 1905 and 1906.

‘Stoneholm’ in Lindfield

Around 1904 Biffin moved to the then outer Sydney suburb of Lindfield where she had purchased the 1880s house Stoneholm in Gordon Road (now the Pacific Highway). The extensive property was marked by Monterey pines, which were a feature of the local landscape for 40 years.[13] Biffin is listed in the Sands Directory as practicing here from 1906, and like another pioneer woman doctor Iza Frances Josephine Coghlan, she successfully operated a concurrent city and suburban practice. At this time Biffin’s nearest medical colleagues were at Pymble and Chatswood, as Sydney’s main medical facilities were in the city, then divided by Sydney Harbour. In 1915 Biffin left her Elizabeth Street city practice, and created a joint practice with Dr Helen Braye in Lindfield, a partnership which lasted until 1926.

Biffin’s Lindfield surgery flourished as a large general practice. Following in the footsteps of her mother, she delivered babies in the district, and was well known and regarded by her community. She was nicknamed ‘Biff’ and ‘was very much a “no nonsense” woman'.[14] She did not take fees from poor patients, and sometimes offered gifts of money or loans. During house calls, 'Dr Biffin wore masculine styled nice suits, complete with vest, and a divided type of skirt, a straw boater, which she invariably placed on the hall table when entering the patient’s house but ... she provided a different spectacle, seated in her dog-cart, complete with groom, as she drove at speed down Pymble Hill to cross the railway line before the gatekeeper swung the gate shut'.[15]

By 1913 her dogcart had given way to a car:

Harriett Biffin was well known, chugging up the road in an old model car. She had iron-grey hair cut short and wore invariably a black Norfolk coat with stiff collar, topped by a straw boater with cord attached.[16]

Biffin was also popular with local children:

Children in the trains which passed the verandah of her house always hoped to receive a greeting in return to their waving hands if she happened to be seated there, and their delight was increased if her peacock was strutting in the garden.[17]

Her nephew said that:

To those who did not know her well, Harriett may have seemed a rather formidable, stern person. She was indeed very direct and forthright when necessary and left those who offended in no doubt about her feelings.[18]

World War I and the Mater

[media]In 1912, Biffin was appointed as the assistant anaesthetist at The Mater Misericordiae Hospital in North Sydney.[19] She also served there as honorary physician from 1913, and The Mater's annual reports list her as paying near to the highest number of visits to patients of all doctors. Biffin was the only female doctor at the hospital until joined by doctors Margaret Harper in 1916 and Susannah Hennessy (Susie) O’Reilly in 1918. All three resigned from the hospital in 1919.

The ethos of The Mater at this time was to provide healthcare to all in the community, regardless of their capacity to pay. From the outbreak of World War I, Biffin and her mother Eliza donated money to the hospital as well as cases of fruit, vegetables and flowers.

Between 1916 and 1917 Biffin treated a young Australian soldier Private Andrew John Godber, recently returned from the Western Front with severe shell shock and assessed as medically unfit. She lodged a written request to the staff officer for invalids at Victoria Barracks to administer medical treatment to Godber in his home, stating she would give progress reports each week to save the department expense.[20]

The war left many Sydney women bereaved and one of these was Greenwich resident and anthropologist Olive Pink, who sought Biffin’s services after her sweetheart was killed in Gallipoli. In 1915 Biffin prescribed a special tonic for her fluttering heart, a prescription Pink took in her travelling medical kit during her later extensive research trips throughout remote Central Australia, and also for the rest of her life.[21]

New South Wales Association of Registered Medical Women

Archival records of early women’s professional medical associations in New South Wales are often scanty. Most associations did not survive beyond a few years, even as increased numbers of women graduated in medicine. In February 1921 Biffin founded the New South Wales Association of Registered Medical Women (by 1928 the Medical Women’s Society of New South Wales) with Dr Lucy Gullett, and served as its inaugural president. The association was formed to advance the interests of qualified medical women in professional practice, and meetings took place in the Women’s Club at Beaumont House, 167 Elizabeth Street, Sydney. Unlike previous professional associations, theirs was a long-standing and successful venture.[22]

Inspired by the women-operated Queen Victoria Memorial Hospital, Melbourne, the association’s first action was the establishment of a much-needed women-operated hospital for Sydney. Similar plans had been discussed as far back as 1898 by Dr Dagmar Berne, who envisaged a hospital in Sydney run by women for women after practicing at The New Hospital for Women, London in the early 1890s.[23] By 1922 the environment in Sydney was right for the establishment of this type of hospital, as infant and maternal welfare had become a subject of significant interest in Australia. In 1923 the association campaigned for equal pay for women doctors in the public service.

The New Hospital for Women and Children, Surry Hills

[media]On 3 January 1922, Biffin and Gullett’s plans for a women’s hospital materialised. Together with Biffin’s mother Eliza and other women doctors and their relatives, they funded the purchase of a small two-storey abandoned terrace house for £1000 at 11 Lansdowne Street Surry Hills for a charitable outpatient dispensary for women and children.

These founding doctors repaired the terrace and named its primitive dispensary The New Hospital for Women and Children, with Biffin serving as honorary treasurer from its outset. It provided two medical clinics each day: a venereal disease clinic, and an eye clinic, and was open three evenings each week for women workers. Doctors made house calls where situations were urgent.

The New Hospital for Women and Children was founded by Biffin and Gullett with a twofold aim: to serve poor women and children with general illness (excluding maternity issues), and to provide Sydney women medical students, graduates and specialists with the necessary professional clinical experience in medicine and surgery.

Biffin and her mother Eliza remained life governors of the hospital.

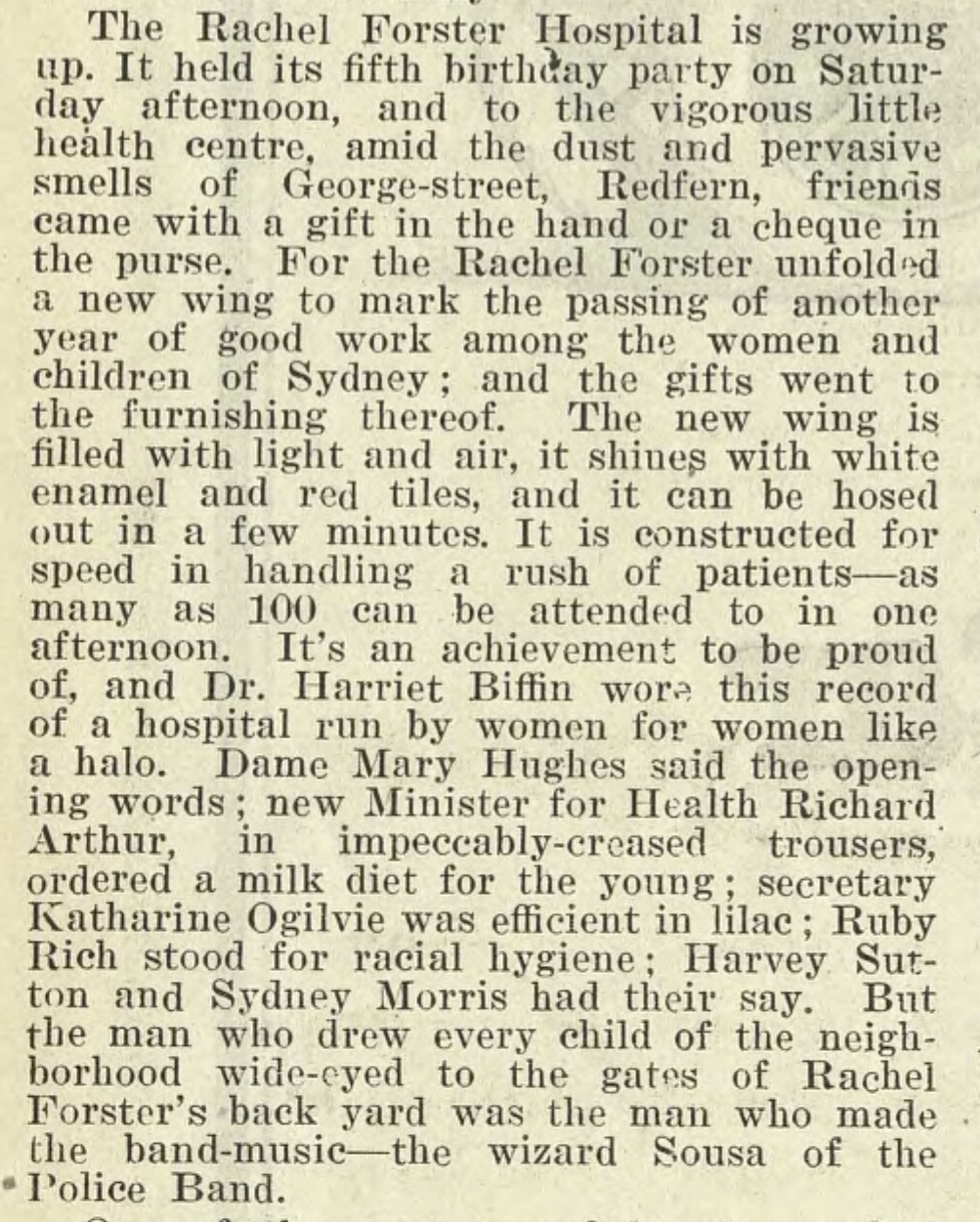

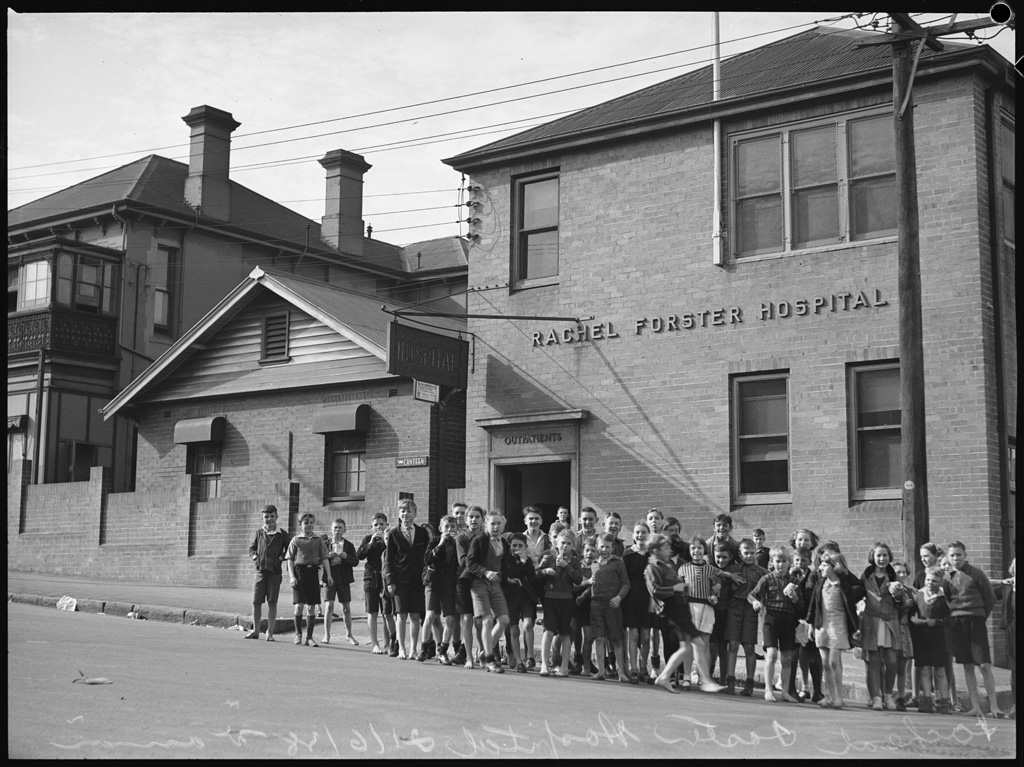

The Rachel Forster Hospital, Redfern

[media]The New Hospital for Women and Children became so popular with Sydney women that it soon needed a larger site. Again Biffin encouraged the raising of necessary funds and ‘was able to rally round her, from among her patients, a tremendous force of willing helpers and contributors'.[24] Biffin and her mainly middle-class women philanthropists raised enough money to purchase a two-storey house with thirteen rooms for £3500 at 195 George Street Street Redfern (now Clyde House) in 1924, which served as a small inpatients hospital with a single public ward. A year later it was renamed the Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children.

The Rachel Forster Hospital offered the first generation of Sydney women medical students and physicians a workplace where they could receive hospital experience. At ‘The Rachel’ their university medical training was valued and rewarded, and they could access specialist knowledge, work in honorary positions and be appointed to senior roles critical to their career development. These were difficult for women doctors to obtain and routinely denied them particularly after World War I when medical servicemen returned from the war.

[media]Biffin’s own experiences as a medical student informed her treatment of new women medical practitioners, and she ensured work was given to young women starting their careers. She insisted on having a female anaesthetist when undertaking surgical work, and claimed in 1923: ‘This hospital was started to afford an opportunity for experience and further training of women doctors - no other hospital affords this.’[25]

The Rachel Forster Hospital developed an outstanding and far-reaching reputation, especially in the areas of gynaecology and paediatrics. It served generations of Sydney women and children, and patients travelled from all parts of Sydney, including wealthier suburbs, to access its unique services. During Biffin’s lifetime it remained a hospital founded, staffed and run by women for women, the longtime dream of herself, Gullett and many other pioneer Sydney women doctors.

Biffin was actively involved in repeated attempts during the 1920s to have the hospital officially recognised by the New South Wales Hospitals’ Advisory Board. She retained her belief it should remain administered by women and fully reliant on philanthropic subscriptions, and was opposed to state financial assistance, which she feared would enable male involvement in the hospital’s governance.

[media]By 1930 the Rachel Forster Hospital was gazetted as a second schedule hospital under the Public Hospitals Act of 1929 after an eight-year struggle. It urgently needed to expand its facilities and land was purchased at 134-150 Pitt Street Redfern. Although she was involved in plans for its development, Biffin did not live to see the large 124-bed modern hospital that opened in December 1941.[00.26]

Retirement and beyond

In October 1928, 60 women doctors entertained Biffin at a dinner and theatre party to mark her retirement from practice at Rachel Forster Hospital. Biffin also retired from private practice in Lindfield around 1929, selling her practice to Dr Marion Galbraith Fox.[26]

Biffin enjoyed a rich private life. She was known for bringing jars of homemade jam to the hospital for patients and staff. She was a classical Greek scholar, loved music, attended performances of visiting opera companies, owned a fibro holiday cottage at Clareville Beach, and took a two-month pleasure trip to Japan in 1934. She owned a 1937-model Chevrolet, collected books on early Australiana, was passionate about Australian history, and had ‘a special admiration for the work of Matthew Flinders’.[27] Mary Livingston, first matron of the Rachel Forster Hospital, remained her companion from the late 1920s until her death.[28]

In 1929 the widening of the Lane Cove Road in Lindfield to enable additions to the main Ku-ring-gai Highway meant that the striking 40-year old pines on her property were earmarked for removal.

The Sydney Morning Herald reported:

Stoneholme has been made famous by its present owner, Dr Harriett Biffin, who purchased the property 26 years ago and began as a medical practitioner when Lindfield was in its infancy. Everyone within miles of the now busy centre knew the doctor personally or by sight, and knew of her good work as well. Her pine trees were a feature of the skyline.

Biffin reflected:

I am sorry to part with my last pine tree. It is one of the links with the past. Many an old resident of Lindfield will miss it.[29]

In 1934-35 Biffin erected two blocks of four brick on stone residential flats on the site of Stoneholm at 295-303 Pacific Highway named Stoneholm Flats.[30]

Biffin’s lifetime philanthropic and medical work was recognised in 1937 with the award of Member (Civil) of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for ‘charitable and social welfare services in the state of New South Wales.’[31]

In memoriam

[media]Biffin worked tirelessly for the Rachel Forster Hospital and its expansion until the last few months of her life. She died on 22 September 1939 aged 72 at Stoneholm in Lindfield and her ashes were placed with those of her cousin Louisa Wilson, the first woman to enrol in pharmacy at the University of Sydney, under a pink camellia tree in the unsectarian section of Gore Hill Memorial Cemetery.[32]

In her obituary in the Medical Journal of Australia, Dr Margaret Harper wrote:

Dr Biffin was a woman of few words, but all who knew her will remember the determined line of her mouth and the expression in her blue eyes when she delivered her considered opinion on a particular problem. Her faith in her women colleagues never faltered, and as women specialists in surgery, paediatrics and pathology gradually appeared, she gave them her wholehearted support.[33]

[media]And a year later in The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children's annual report, Harper claimed: ‘She, more than anyone, broke down the early prejudice against women in medicine.’[34]

To commemorate her life, Biffin Street was gazetted in the suburb of Cook in the Australian Capital Territory in 1969.[35]

References

Louella McCarthy, 'Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939', UNSW PhD Thesis, 2001

Notes

[1] Roseville Community Association Inc, William Henry’s 40 Acres and The People Who Lived There: Then and Now (Roseville, NSW: Roseville Community Association, 2000), 18-19

[2] Examination Ledgers, 1884-1939, University of Sydney Archives: Matriculation Exam Results 1887 and 1888 cited in Louella McCarthy, ‘Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939’ (PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2001), 44; University of Sydney, Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1887 p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28355728 viewed 15 November 2018

[3] Roseville Community Association Inc, William Henry’s 40 Acres and The People Who Lived There: Then and Now (Roseville, NSW: Roseville Community Association, 2000), 19

[4] See the treatment of the first woman medical student Dagmar Berne who never progressed beyond the first professional examinations at the University of Sydney medical school in the 1880s, Vanessa Witton, 'Dagmar Berne's Story', Radius, Winter 2008, 30–31, http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/documents/Dagmar.pdf, viewed 18 October 2018

[5] Sir Frederick Chilton, The Warrawee Chiltons, (Sydney, NSW: F Chilton, 1985), 54-55; University of Sydney Calendar Archive 1887-1898, http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/index.php, viewed January 2, 2013

[6] New South Wales Medical Board, Register of Medical Practitioners New South Wales, vol 1897-1913

[7] Eric Hilder, One Hundred and Twenty Years of Medical Registration in New South Wales 1838-1958, compiled from the records of the New South Wales Medical Board by Eric Hilder, (Sydney: n.p., c1959), 107

[8] Louise Baur, Roderick Best, ‘The Forgotten Dr Ellen Wood,’ Radius, March, 2013, 28-29

[9] New South Wales Medical Board, Register of Medical Practitioners New South Wales, vols 1897-1913; 1914-25

[10] Mitchell Library, 363/W, ‘Women's Australian Natives' Association (Registered Under the Friendly Societies Act): A Patriotic, Literary, Mutual Improvement and Sound Benefit Society, to Assist, to Aid, to Relieve’, (Sydney: Women's Australian Natives' Association, 1903), 2

[11] The Doctors and the Friendly Societies, Sydney Morning Herald, 24 August 1903, 6

[12] Louella McCarthy, ‘Finding a Space for Women: The British Medical Association and Women Doctors in Australia, 1880-1939,’ Medical History, 62 (No. 1), 2018, 103-104

[13] According to letters written by Margaret (Madge) Doak, a prior tenant of Stoneholm 1895-1897, Stoneholm then was a pretty cottage on one acre of ground. In these letters Doak describes the dwelling as covered with virginia creeper vine that turned scarlet in autumn. The plentiful paddock and garden yielded roses, magnolias, gardenias, chrysanthemums, and a small orchard of peaches, blackberries, figs, apples, nectarines, passionfruit and strawberries. Butcherbirds, magpies and thrush warbled in the garden. Doak noted that all along the railway line were orchards with peaches, plums, apricots and pears. Letter 11 - 15, Association of the Bucknall Family website, Bucknall.org.au, Madge Doak’s letters to Mary, transcribed by Mark Roberts ,http://bucknall.id.au/Rodborough/Madge%20Doak%20Letters.pdf, viewed February 12, 2018; ‘Last of the pines: widening of Lane Cove Road’, Sydney Morning Herald, 18 December 1929, 21

[14] Sir Frederick Chilton, The Warrawee Chiltons, (Sydney: F Chilton, 1985), 56 cited in Louella McCarthy, ‘Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939’ (PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2001), 78

[15] ‘Recollection of Una Roberts of Gordon in Ku-ring-gai Historical Society,’ The Historian Vol 8 no 3, (Sept 1979), 8

[16] Ku-ring-gai Historical Society, The Historian Vol 36 no 1, (Oct 2007), 18

[17] Margaret Harper, ‘Obituary, Harriett Eliza Biffin,’ The Medical Journal of Australia, 7 October1939, 559

[18] Sir Frederick Chilton, The Warrawee Chiltons, (Sydney: F Chilton, 1985), 56 cited in Louella McCarthy, ‘Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939’ (PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2001), 78

[19] The Mater Misericordiae Hospital for Women and Children Annual Reports for the Years Ending December 1912 – December 1919

[20] Private email communication in 2013 between the author and Kathy Rieth, Ku-ring-gai Historical Society, Sydney; Letter from Dr Biffin to the Staff Officer for Invalids, Victoria Barracks, Sydney 4 November 1916, on his discharge from the No 4 AGH Randwick, in Godber Andrew John : SERN 4189 : POB Bombala NSW : POE Holsworthy NSW : NOK F Godber D J, National Archives of Australia (Series: B2455) https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/records/179571/21, viewed 18 October 2018

[21] Julie Marcus, The Indomitable Miss Pink: A life in Anthropology (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2001), 29, 50, 89, 107, 295

[22] Vanessa Witton, ‘Rachel Forster Hospital’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2015, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/rachel_forster_hospital, viewed April 8, 2015

[23] Vanessa Witton, ‘Berne, Dagmar’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2014, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar, viewed December 31, 2014

[24] Margery Scott-Young, ‘Rachel Forster Hospital 1922 to 1972: The Founders,’ The Medical Journal of Australia, 15 July 1972,142

[25] State Records NSW, Department of Public Health, 10/43027, Correspondence Case Files 1928-42, Harriett Biffin to Dr Robert Dick, Director General of Public Health, 9 December 1923 cited in Louella McCarthy 'Idealists or Pragmatists? Progressives and Separatists Among Australian Medical Women, 1900-1940,’ Social History of Medicine 16 no 2 (August 2003), 266

[26] Vanessa Witton, ‘Rachel Forster Hospital’, Dictionary of Sydney, 2015, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/rachel_forster_hospital, viewed April 8, 2015

[27] State Records of New South Wales, Probate Jurisdiction, Harriett Eliza Biffin, November 2, 1939, Probate Packet No 13660 Gore Hill Memorial Cemetery: Biographies vol 1 (Sydney: Friends of Gore Hill Cemetery, 1994), 326-27; State Records of New South Wales, Probate Jurisdiction, Harriett Eliza Biffin, November 2, 1939, Probate Packet No 13660. In 1915 the land and cottage in Beach Parade, Clareville Beach was purchased with Biffin’s cousin Louisa Wilson (Junior), and in 1929 was co-owned by Biffin’s companion Mary Livingston.

[28] Margaret Harper, The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children Eighteenth Annual Report 1940 (Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Co., Ltd, 1940), 3-5

[29] Last of the Pines: Widening Lane Cove Road, Sydney Morning Herald, December 18, 1929, 21

[30] Private email communication in 2013 between the author and Kathy Rieth, Ku-ring-gai Historical Society, Sydney

[31] Louella McCarthy, ‘Uncommon Practices: Medical Women in New South Wales 1885-1939’ (PhD Thesis, UNSW, 2001), 204; State Records of New South Wales, Probate Jurisdiction, Harriett Eliza Biffin, November 2, 1939, Probate Packet No 13660

[32] Louisa Wilson (Junior) was the first woman in New South Wales to qualify as a pharmacist by examination. Her builder father Edward King Wilson built a chemist shop for her in front of the family home in Killara (now Pacific Highway) that she opened in 1904. She died of pneumonic influenza during the epidemic of 1919-20. See Roseville Community Association Inc, William Henry’s 40 Acres and The People Who Lived There: Then and Now (Roseville, NSW: Roseville Community Association, 2000), 19

[33] Margaret Harper, ‘Obituary, Harriett Eliza Biffin,’ The Medical Journal of Australia, 7 October 1939,559

[34] Margaret Harper, The Rachel Forster Hospital for Women and Children Eighteenth Annual Report 1940 (Sydney: Australasian Medical Publishing Co., Ltd, 1940), 3-5

[35] ACT Planning and Land Authority, http://www.actpla.act.gov.au/home, accessed January 2, 2013