The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Leadbeater, Charles

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Leadbeater, Charles Webster

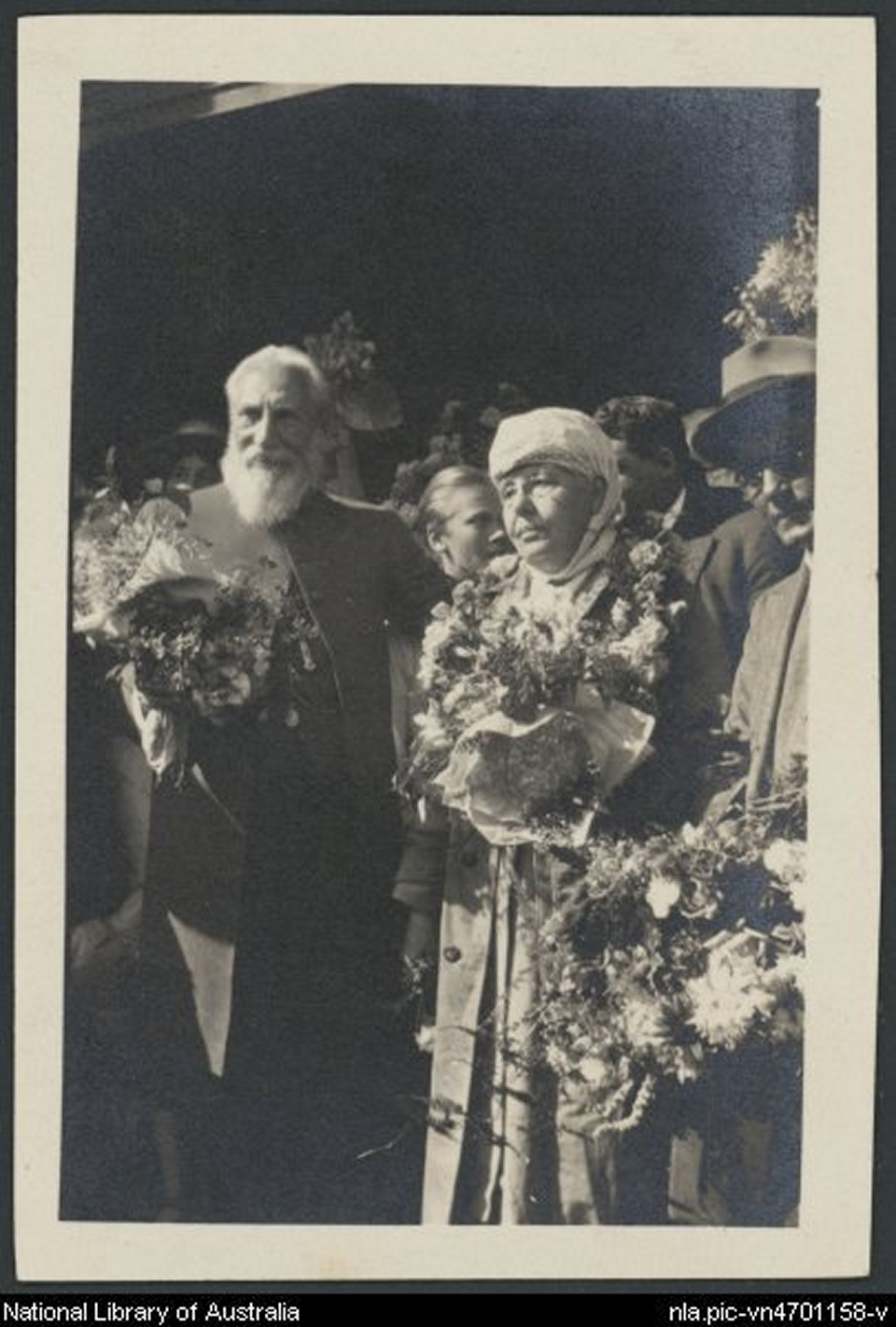

Sydney [media]has a history of colourful religious figures, but few clerics have carried more of a whiff of scandal than Bishop Charles Leadbeater, who graced Sydney while ministering to both the city's Liberal Catholic community and its theosophists; his was not a career prefigured when he was born in regional England in the mid-nineteenth century.

Leadbeater had led an unusual life even before he arrived in Sydney in 1914. He was born in Stockport in England in 1854, the son of a bookkeeper and his wife. Despite little theological training, he was made a deacon of the Anglican Church by the Bishop of Winchester in December 1879, and anointed as a priest the following year. [1] But he dabbled in spiritualism and the occult, and in 1882 he joined the very 'high-church' Anglo-Catholic 'Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament'. The next year he joined the Theosophical Society.

In 1884 he met Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the society's founder, when she came to London. The meeting was life-changing for Leadbeater – he gave up the church, and followed Madame Blavatsky to India. He spent the next five years in India and Sri Lanka (then Ceylon). Returning to London in 1889, he became a confidante of Mrs Annie Besant, who, after a political struggle on the death of Madame Blavatsky in 1891, became leader of the theosophists; Leadbeater eventually became her second-in-command in the society.

Leadbeater's duties took him back and forth around the world, and an early scandal involved young boys in his charge, one of whom was Hubert van Hook of Chicago, who as an 11-year-old had already been proclaimed by Leadbeater as the holy 'Lord Maitreya', the future 'World Teacher' that the Theosophists were expecting soon to appear. This led to a falling out with Mrs Besant, and Leadbeater resigned from the Theosophical Society in 1906, but was gradually accepted back by them, rejoining the society in 1909. Later that year, while in the Society's headquarters in Adyar, Madras (now Chennai) India, he 'discovered' on a nearby beach an Indian boy, Jiddu Krishnamurti, whom he claimed would become the 'World Teacher'. Leadbeater believed he could read past lives, and he published 30 of Krishnamurti's 'past lives' in the society's magazine The Theosophist.

Leadbeater comes to Sydney

Mrs Besant had come to see Leadbeater as a liability to the society, and was relieved when, after an initial visit to Sydney in 1914, he decided to stay. Leadbeater soon became acquainted with James Ingall Wedgewood, a former General Secretary of the Theosophical Society in England and Wales, who had come to Australia in 1915 as Grand Secretary of the Order of Universal CoMasonry, a form of Freemasonry which admits both men and women, and which began in France in the mid-nineteenth century with the forming of Le Droit Humain. In 1916 Westwood initiated Leadbeater into Freemasonry, and then ordained him a 'bishop' of the Old Catholic Church, which in 1918 became the Liberal Catholic Church. This church derived its orders from the Old Catholic Arch-Episcopal See of Utrecht in Holland: it was neither Roman Catholic nor Protestant, and was called Liberal Catholic because its outlook was to be both liberal and Catholic. It aimed at combining Catholic forms of worship, described as 'stately ritual, deep mysticism and witness to the reality of sacramental grace', with 'the widest measure of intellectual liberty and respect for the individual conscience'. [2] In 1922 Leadbeater succeeded Wedgwood as 'presiding bishop' of the Church. In that same year, the Theosophical Society began renting a mansion known as The Manor in the Sydney suburb of Mosman. Leadbeater took up residence there as the leader of a community of theosophists.

Spiritualism, séances and other forms of mysticism seemed to find a ready audience in Sydney in the 1920s, and Leadbeater, in his role of Co-patron of the Order of the Star of the East with Mrs Annie Besant (who visited Sydney in 1922), guided the construction of the Star Amphitheatre at Balmoral Beach. Completed in 1924, and built in the Grecian Doric style, it cost about ₤10,000, had seating accommodation for 2,500 people, and was intended as a venue for lectures by the expected 'World Teacher', still believed by theosophists to be Krishnamurti. In 1925 Krishnamurti came to Sydney, staying at another house in Mosman while meeting the city's theosophist community. [3] There were also stories that the Amphitheatre was so located for the best view of the expected 'second coming' that would see Jesus Christ come through the Heads of Sydney Harbour. [4] This did not eventuate however, and the Balmoral Amphitheatre was demolished in 1951.

Leadbeater was certainly a flamboyant Sydney character. Jack Lindsay in his autobiography noted that he occasionally saw the Bishop 'in doddering patriarchal gravity amble across Circular Quay with a bevy of pretty acolytes'. [5] Mary Lutyens, the biographer of Krishnamurti who spent time in Sydney in the 1920s with the Theosophists, left this description of Leadbeater

prancing down the wharf like a great lion…hatless and in a long purple cloak, holding on to the arm of a very good-looking blond boy of about fifteen. This was Theodore St John, an Australian boy of great charm and sweetness, who was Leadbeater's current favourite and who slept in his room. [6]

Leadbeater's career was dogged by claims of sexual impropriety with boys. These had first surfaced in 1906, in both England and the United States, relating to teenage boys that Leadbeater had under his wing in the course of his theosophist duties. In Sydney in 1918, dissident theosophists in California brought to the notice of the New South Wales Attorney-General those earlier allegations, and police investigations were made, as Leadbeater now had charge of a number of children of Australian theosophists. The inquiries were inconclusive, as were a further series following new accusations in 1922. No charges were laid, but the press reports of the second affair sparked a scandal. [7]

Leadbeater occasionally returned to Adyar, and while there in 1925 came across the very young Australian Peter Finch, who was there with his grandmother Laura Finch. A biographer of Finch wrote

from Dr Besant, Peter had lessons in meditation; 'Bishop' Leadbeater was more noted for his lessons in masturbation. [8]

These masturbatory practices, which Leadbeater was accused of teaching to teenage boys, caused most outrage. [9] He taught that the energy aroused in masturbation can be used as a form of occult power, a great release of energy which can, firstly, elevate the consciousness of the individual to a state of ecstasy, and, secondly, direct a great rush of psychic force towards the Logos for his use in the spiritual development of the world. As he put it, 'The closest man can come to a sublime spiritual experience is orgasm.' [10]

Such an explanation found little favour in Sydney in the 1920s.

Leadbeater left Australia for Adyar in 1929, to take over the leadership of the Theosophical Society from Mrs Besant, whose health was failing. He returned to Sydney for short periods in 1930 and 1932, but died in Perth in 1934. [11] Leadbeater was cremated in Sydney, and his ashes were distributed among various theosophical centres around the world.

Leadbeater's Sydney legacy, then, is more to be found in stone and scandal, than in saved souls: today, there is only one Liberal Catholic Church in the city – the Church of St Francis and St Alban in St John's Avenue, Gordon. The first Liberal Catholic Church in Sydney, that of St Alban, originally at 52 Regent Street Chippendale and next door to the St Alban's Co-Masonic Temple, was dedicated in 1918. These two sites were at the centre of the Sydney theosophical movement in the 1920s and 1930s, but they were demolished in 1965, and a new St Alban's Church was consecrated at 9 Stanley Street in East Sydney later in that decade; it has now closed. And while there was the spectacular Balmoral Star Amphitheatre, it has long since been demolished.

References:

Gregory Tillett, The Elder Brother: A Biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1982

WG McMinn, 'Leadbeater, Charles Webster (1854–1934), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 33–34

Jill Roe, 'Three visions of Sydney Heads', in Jill Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney: Studies in urban and social history, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1980

Notes

[1] WG McMinn, 'Leadbeater, Charles Webster (1854–1934), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 33–34

[2] Liberal Catholic Church, Statement of Principles, 8th edition, 1986, quoted in Pedro Oliviera, 'Work for the Liberal Catholic Church', Charles Webster Leadbeater website, http://www.cwlworld.info/html/liberal_catholic_church.html, viewed 24 August 2010

[3] HYPERLINK "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Webster_Leadbeater" http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Webster_Leadbeater, accessed 17 August 2010

[4] Jill Roe, 'Three visions of Sydney Heads', in Jill Roe (ed), Twentieth Century Sydney: Studies in urban and social history, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1980, pp 92–104

[5] Jack Lindsay, The Roaring Twenties, Penguin, Sydney, 1982, p 179

[6] Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening, Avon Books, New York, 1983, p 202n, quoted in http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Webster_Leadbeater, accessed 17 August 2010

[7] See for example, Melbourne Truth, 27 May 1922, where the 'certain practices' are alluded to. More details are in Melbourne Truth, 3 June 1922, 16 June 1922 and 24 August 1929

[8] IM Britain, 'Finch, Frederick George Peter Ingle (1916–1977)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, pp 163–164

[9] Gregory Tillett, The Elder Brother: A Biography of Charles Webster Leadbeater, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1982, chapters 9 and 17

[10] Gregory Tillett, 'Charles Webster Leadbeater 1854–1934: A biographical study', PhD thesis, University of Sydney, 1986, p 905, available online at http://leadbeater.org/tillettcwlcontents.htm, viewed 13 April 2011

[11] IM Britain, 'Finch, Frederick George Peter Ingle (1916–1977)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 14, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1996, pp 163–164