The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Pemulwuy

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Pemulwuy

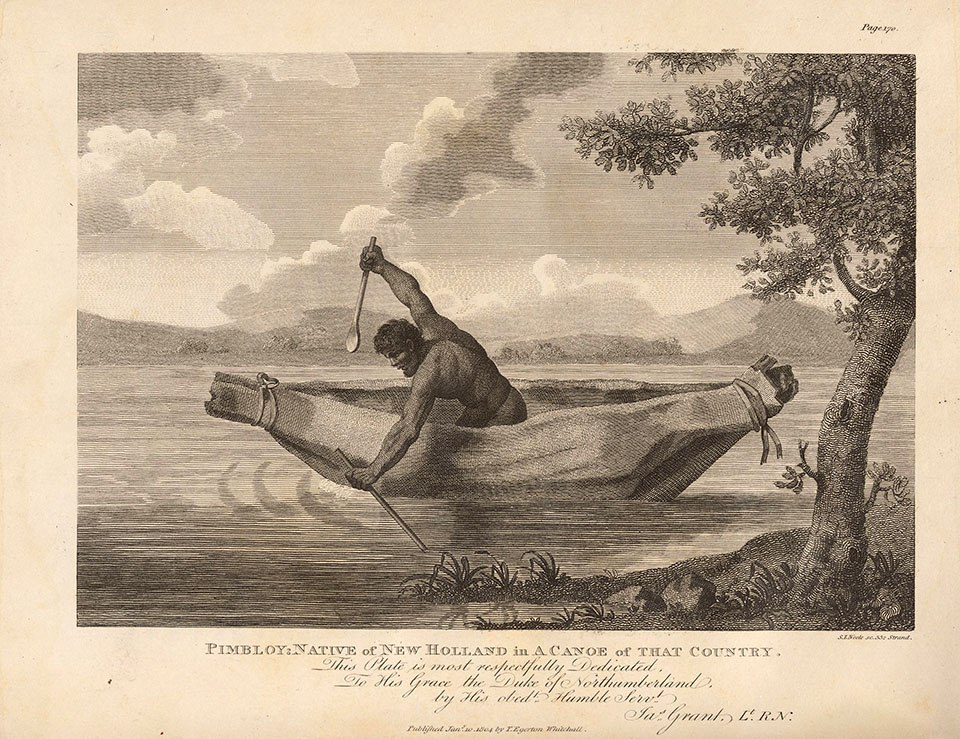

Pemulwuy [media]was a powerful Aboriginal resistance leader against the British settlers who occupied his land. He took the fight to the government farm at Toongabbie and stormed into the town of Parramatta at the head of 100 warriors. His exploits and bravery made Pemulwuy the stuff of myth and legend. Governor Philip Gidley King considered Pemulwuy 'an active, daring leader of his people' and wrote that 'Altho' a terrible pest to the colony, he was a brave and independent character'. [1] In Pemulwuy, the rainbow warrior, a brilliant work of fiction, Eric Willmot constructed a black hero for Australia's Aboriginal community.

The colonists first heard about Pemulwuy in October 1790 when Woollarawarre Bennelong asked a marine sergeant and his troops searching for a missing convict to join a war party to kill Pemulwuy. This was just 10 days after the peaceful 'coming in' of the Eora (coastal Aborigines) to the Sydney settlement, negotiated between Bennelong and Governor Arthur Phillip.

Bennelong said Pemulwuy, then aged about 30, was 'well known for having lost an eye' and was the leader of a clan at Botany Bay. [2] Captain Watkin Tench described him as a 'young man, with a speck, or blemish on his left eye'. [3] Pemulwuy's name was derived from Pemall (bimul), meaning earth or clay.

Through the final decade of the eighteenth century, Pemulwuy led guerrilla attacks against settlers' farms, burning their huts, maize crops and livestock, and plundering their possessions. He operated mainly in his own Bidjigal or Bediagal territory, which stretched from Botany Bay south of the Cooks River and west along the Georges River to Salt Pan Creek, south of Bankstown. (There was another clan called the Bidjigal in the present Castle Hill area, but according to Colebee and Ballooderry (1791) they had been wiped out by smallpox). Georges River was regarded as the 'head' of Botany Bay while Cooks River was its north arm. Bidjigal literally means 'River Flat Clan'.

Bennelong told Phillip that

the tribes which reside about Botany-Bay and the inland parts near the head of that harbour always killed the white men.

There is evidence that Pemulwuy was a carradhy, a clever man or doctor, who could heal wounds. Colebee, the Cadigal headman, told Governor Phillip that Pemulwuy could easily be recognised because a club had bruised the toes of his left foot. Anthropologists have noted that kadaicha men of Central Australia dislocate their small toes to travel swiftly and quietly in shoes of blood and emu feathers to take vengeance on an enemy. In Willmot's version, Pemulwuy transforms himself into a bird to escape.

Although Bennelong called Pemulwuy his enemy, it can be seen in hindsight that Bennelong and Colebee collaborated with Pemulwuy in the killing of Governor Phillip's game shooter, the convict John McEntire or McIntyre. In November 1790 Pemulwuy came to Sydney and stayed for two weeks in Bennelong's brick hut at Tubowgulle (Bennelong Point). Phillip noted that

a man belonging to the Botany-bay tribe had for more than a fortnight slept at his hut, though [Bennelong] said the man was bad, and spoke of him as his enemy.

On Friday 10 December 1790 McEntire was resting in a hide with a hunting party near Cooks River when they heard a noise in the bush and saw four Aboriginal men crawling towards them. 'Don't be afraid, I know them,' said McEntire, who spoke to the men in their own language, asking them to stop and offering them bread. McEntire believed Pemulwuy had been in Sydney because he was clean-shaven and had short hair. As the game shooter put down his gun, Pemulwuy stood on a log, fixed a spear in his womera (spear thrower) and threw it. 'I am a dead man', cried McEntire.

The jagged spearhead penetrated deep into McEntire's body, perforating his lung. When he extracted the spearhead, Surgeon John White found that it was barbed with 'small pieces of red stone' (silcrete flakes).

To show they were not at Cooks River during the attack on McEntire, Colebee and Bennelong separately travelled to Rose Hill (Parramatta) to visit Phillip that day. [4] Three months earlier they had called in Willemering, a carradhy from Broken Bay, who speared and wounded Phillip at a whale feast at Kayeemy (Manly Cove).

Colebee told the surgeons that McEntire would die and other 'natives' in the settlement said 'Pemullaway, of the tribe of Bejigal' had speared him.

McEntire lingered but died of his wounds on 20 January 1791. Bennelong had long feared and hated McEntire, who carried a musket and competed for food with the Indigenous people. He was trespassing on Bidjigal land and shooting totem animals revered as spirit ancestors, including possum, kangaroo, emu and dingo. 'This man', wrote Judge Advocate David Collins, 'had been suspected of having wantonly killed or wounded several of the natives in the course of his excursions after game.' McEntire admitted shooting one Aboriginal man.

Convinced that the attack on McEntire was unprovoked as he had not been armed, Phillip ordered a punitive expedition of 50 marines, led by Tench and carrying hatchets and head bags, to kill six Indigenous men at Botany Bay and capture two for execution. On the second day they met Colebee at Botany Bay, who told them Pemulwuy had fled to the south and was by that time a long way off. The expedition was a failure, and a second one was a farce.

David Collins noted that in January 1795 'Pe-mul-wy, a wood native' came in as sponsor of a youth being initiated in the Erah ba-diahang ceremony at Woccanmagully (Farm Cove), but no attempt was made to detain or arrest him. In May Pemulwuy's followers wounded a convict near the Brickfields (Chippendale). In December a report circulated that John Caesar, a giant African convict, had killed Pemulwuy, but this turned out to be false. Runaway convicts joined Pemulwuy and a proclamation was issued calling on them to surrender.

The Battle of Parramatta

In March 1797 Pemulwuy led a raid against the government farm at Toongabbie. After a series of robberies at the Northern Farms (near Burnside Homes, Parramatta), a vigilante group of armed settlers and soldiers encountered more than 100 hostile Aborigines at sunrise and chased them to the outskirts of Parramatta. Tiring of the chase, the punitive party entered the town, but an hour later Pemulwuy and 'a large body of natives' followed them and Pemulwuy, in a rage, speared a soldier. Many spears were thrown and the settlers opened fire, killing at least five Aboriginal warriors with the first volley. Pemulwuy was severely wounded, with seven buckshot lodged in his head and body, and was taken to hospital. A later historian and journalist, John Henniker Heaton (1873), claimed that half the Aborigines – 50 people – were shot in the fighting. [5]

Pemulwuy recovered and escaped from Parramatta hospital in irons. He was seen soon after at a point on the Georges River near Botany Bay. In 1800 John Washington Price, newly arrived on the Minerva, said 'Pummil-woy' had

lodged in him, in shot, slugs and bullets about eight or ten ounces of lead, it is supposed he has killed over 30 of our people. [6]

The legend grew that Pemulwuy could not be killed by firearms, but in the end he proved mortal.

On 1 [media]May 1801 Governor King gave orders to drive back 'hordes of natives' around Parramatta, the Georges River and Prospect Hill by gunfire. He outlawed convicts William Knight and Thomas Thrush who had joined the Aboriginal resistance. In November, troops were sent to Mill Creek on the Georges River and King offered rewards including free pardons for convicts and 20 gallons of spirits for their capture and that of Pemulwuy who was wanted 'dead or alive'.

On 2 June 1802, Pemulwuy was shot dead and decapitated.

In October 1802, Governor King advised Lord Hobart at the Home Office in London that

two settlers, not having the means of securing the person of Pemulwuye and another native, shot them.

The governor alleged that other Aborigines had asked for Pemulwuy's head to be cut off and sent to him. The notion of a single killer was suggested by David Dickinson Mann, the governor's clerk, who wrote in 1811 that King had offered a reward

to any person who should kill him and bring in his head. This was soon accomplished by artifice, the man received the reward, and the head was sent to England in spirits by the Speedy.

Suspicion falls on Henry Hacking, first mate of the sloop Lady Nelson, then lying in Sydney Cove. Samuel Smith, a seaman on HMS Investigator, wrote in his journal for 20 July 1802 that

Bumbleway … a Severe Enemy to White people, as he had kill'd several … was shot by the Master of the Nelson Brig, that was shooting in the Woods, his head being brought Tranquility was again restor'd.[7]

Samuel Enderby wrote to Sir Joseph Banks from Paul's Wharf in London on 24 November 1802:

Mesrs Enderbys present their most respectful compliments to Sir Joseph Banks and take the liberty of acquainting him that their Ship Speedy, Geo. Quested, Master is arrived from Port Jackson with 179 Tuns Sperma Ceti Oil – The Master says he has a Black Swan, a Native's Head in Spirits and a number of other things for Sir Joseph Banks – [8]

Banks advised King in April 1803 that

the head of one of your subjects, which is said to have caused some Comical consequences when opened at the Customs house … makes a figure in the Museum of the Late Mr Hunter.

The Scots surgeon and anatomist John Hunter was not related to Captain John Hunter, later governor of New South Wales.

In the nineteenth century Pemulwuy's head was known to be in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Its location is now unknown.

References

Eric Willmot, Pemulwuy, the rainbow warrior, Weldon, McMahons Point NSW, 1987

JL Kohen, 'Pemulwuy (c1750–1802)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, supplementary vol, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2005, pp 318–19

KV Smith, 'Australia's oldest murder mystery', Sydney Morning Herald, 1 November 2003

Notes

[1] PG King to Lord Hobart, 30 October 1802, Public Record Office, London , CO 201/22/6-7; King to Sir Joseph Banks, 5 June 1802, Historical Records of New South Wales, vol V, p 784

[2] Phillip in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson, John Stockdale, London, 1793, pp 473–74

[3] Watkin Tench, A complete account of the expedition to Botany Bay, J Debrett, London, 1793, p 89

[4] Phillip in John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson, John Stockdale, London, 1793, pp 489–90

[5] J Henneker Heaton, Australian Dictionary of Dates and Men of the Time: containing the history of Australasia from 1542 to date, George Robertson, Sydney, 1879

[6] JW Price, Journal on Minerva, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, BL Add MS 13880, AJCP reel 1574

[7] Samuel Smith, Journal on board Investigator and Porpoise under Captain Matthew Flinders, 26 May 1801-7 October 1803, written after 1813, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library SAFE/C 222 (Safe 1/254)

[8] Samuel Enderby, 'Paul's Wharf', to Sir Joseph Banks, 24 November 1802, State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Library, Banks Papers, Series 23.19, CY Reel 3008185

.