The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Socialist Opposition to World War I

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Socialist Opposition to World War I

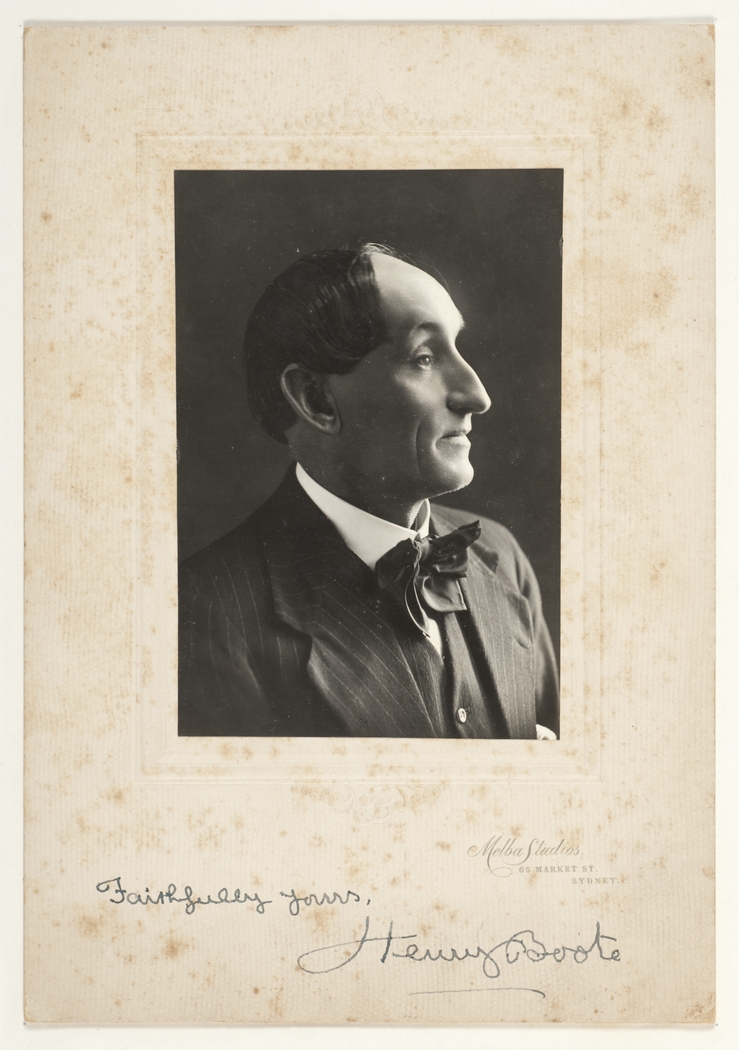

Most socialist organisations opposed the war from the beginning. Socialists abhorred war because, in their worldview, rival capitalists created international conflicts in their quest for markets and profits. The capitalists' exploitation of workers was heightened in times of war as traditionally it was the workers who fought while the ruling class profited. Conscription was viewed in a similar way: '…essentially a class measure, entailing hardships on the poor and exemptions for the rich'. [1] Henry Earnest Boote's Sydney-based newspaper the The Worker certainly upheld these ideas. [media]Boote was the editor of the The Worker, the official organ of the Australian Workers' Union. He strongly opposed the senseless horrors of the brutal war in Europe and he wrote brilliant and biting editorials against it. His newspaper was in the vanguard of galvanising the political movement against conscription. [2] Police regularly raided Boote's newspaper offices looking for articles or evidence that might contravene the War Precautions Act. In December 1917, Boote found himself in Sydney's Central Police Station and Court House for publishing articles that had not been submitted to the censor. Moreover, one of his anti-conscription articles called 'The Lottery of Death' was deemed 'prejudicial to recruiting'. 'Conscription', he had written,

…is to take the form of a lottery. Lives are to be drawn for on Tattersall principles; souls to be made the subject of a hideous sweep...eligible males are to be tossed into a hat or something; then someone – Death, who knows? plunges in a hand, and all who are drawn are doomed to be victims of bloody war. It is the most immoral of all forms of gambling. It is fraught with tragedy; red with murder and foul with abomination. [3]

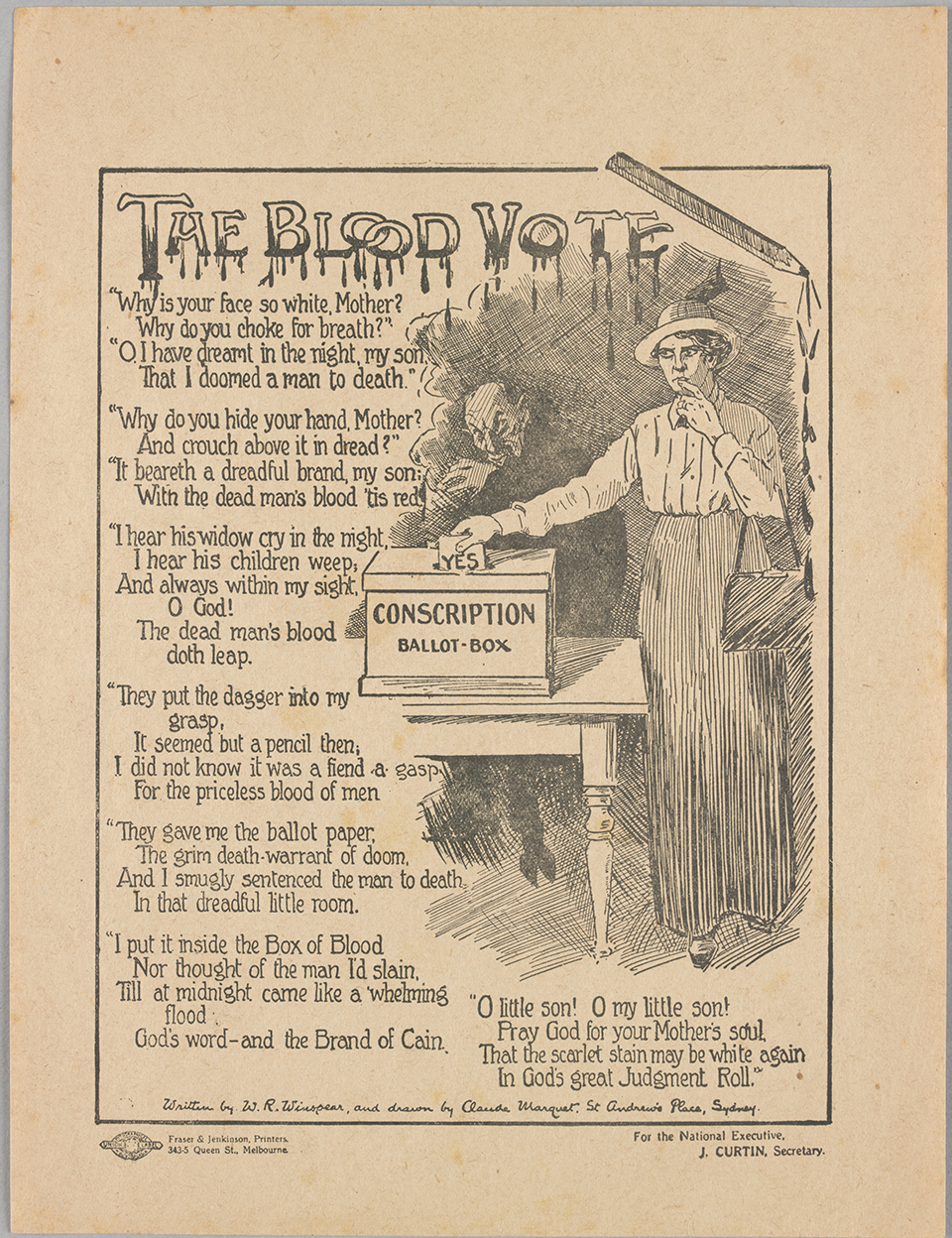

[media]For this written tirade, Boote was ordered to pay £100 or go to jail with three months hard labour. [4] Despite this, he defied the authoritarian official censor and throughout 1916 and 1917 continued to publish a large body of work furiously critical of the governments' conduct of the war. According to the conscription historian Leslie Cyril Jauncey, during the anti-conscription years The Worker printed 5,000,000 pamphlets and leaflets, 400,000 'protests' against conscription, over 100,000 extra newspapers, 500,000 'How to Vote' cards, 250,000 stickers and 25,000 referendum posters. Francis Ahern, RJ Cassidy and the cartoonist Claude Marquet also vigorously attacked conscription and censorship in the pages of The Worker. [5]

Boote was a brilliant and prolific orator. In December 1917 he spoke to an overflowing meeting at the Sydney Town Hall. His subject was conscription in New Zealand 'and the shocking treatment' that conscientious objectors there were receiving. The New Zealand Military Service Act of 1916 made little provision for the conscientious objector: all men between the ages of twenty and forty-six were eligible to be called up and this even included men who adhered to a pacifist Christian faith and religious ministers. [6] Hundreds of men who had refused to enlist were imprisoned and subjected to physical punishment, torture and dietary deprivation in an effort to make them relent. They were also denied their civil rights including the right to vote for ten years. Boote warned his audience that 'what was happening in New Zealand today might happen in Australia tomorrow.' Cheers and hurrah's erupted in the big and adoring crowd that night. Boote was talking to an anti-conscription audience and it seems his listeners needed little convincing. [7]

However, there were other sections of the community who resolutely opposed Boote's sentiments towards conscientious objectors. While he preached against the horrors they faced under compulsory conscription, others execrated them as 'wasters', 'selfish shirkers', 'slackers' and 'pacifist wastrel cowards'. One letter published in The Sydney Morning Herald exemplifies the heightened sensitivities and the strength of feelings that were aroused by this divisive and discordant issue. In July 1916 the paper printed a letter from WF Ogilvie of Glen Innes. In it, he expressed his candid opinion of the conscientious objector:

I ask my fellow Australians to wipe out this extraordinary, rotten person – the conscientious objector. He's an excrescence on society, which a virile community should not allow for one moment to exist, not even to draw one tainted breath… To my way of thinking, the first shot from each and every soldier's rifle should find its home in a conscientious objector.' [8]

[media]On 28 October, 1916, in New South Wales, 356, 805 people voted 'yes' to conscription and 474, 544 voted 'no'; the 'no' vote in New South Wales won by a 117, 739 majority. [9] At the second conscription referendum, held on 20 December, 1917, in New South Wales, 341, 256 people voted 'yes' and 487, 774 voted 'no'; again the 'no' vote in New South Wales won by a slighter larger 146, 518 majority. [10] New South Wales produced the largest 'no' vote out of all of the states in both referendums. Yet many thousands of people had voted 'yes' which serves to illuminate a state divided over the issue. Compulsory conscription was twice defeated by the people's vote and it was not introduced. Accordingly, conscientious objection did not feature in the Australian experience of World War I. As such, the repressive persecution handed out to conscientious objectors in both New Zealand and Great Britain did not become a reality for men in Australia. But it begs the question – what if conscription had been made compulsory?

In New South Wales the 'no' vote was won with large majorities because many opposed conscription. Reasons were varied: some saw it as a question of freedom of choice and liberty of conscience; others upheld the principle of volunteer enlistment. Others, such as the Sydney businessman and rationalist William John Miles, opposed Imperial Federation and believed in putting Australian interests first. [11] Some opposed the war on moral or pacifist grounds and quite simply rejected the compulsion of the draft. [12] Had it been introduced our military history would have indeed been different and the conscientious objector would, out of necessity, have had to have been written into it. [13]

Industrial Workers of the World

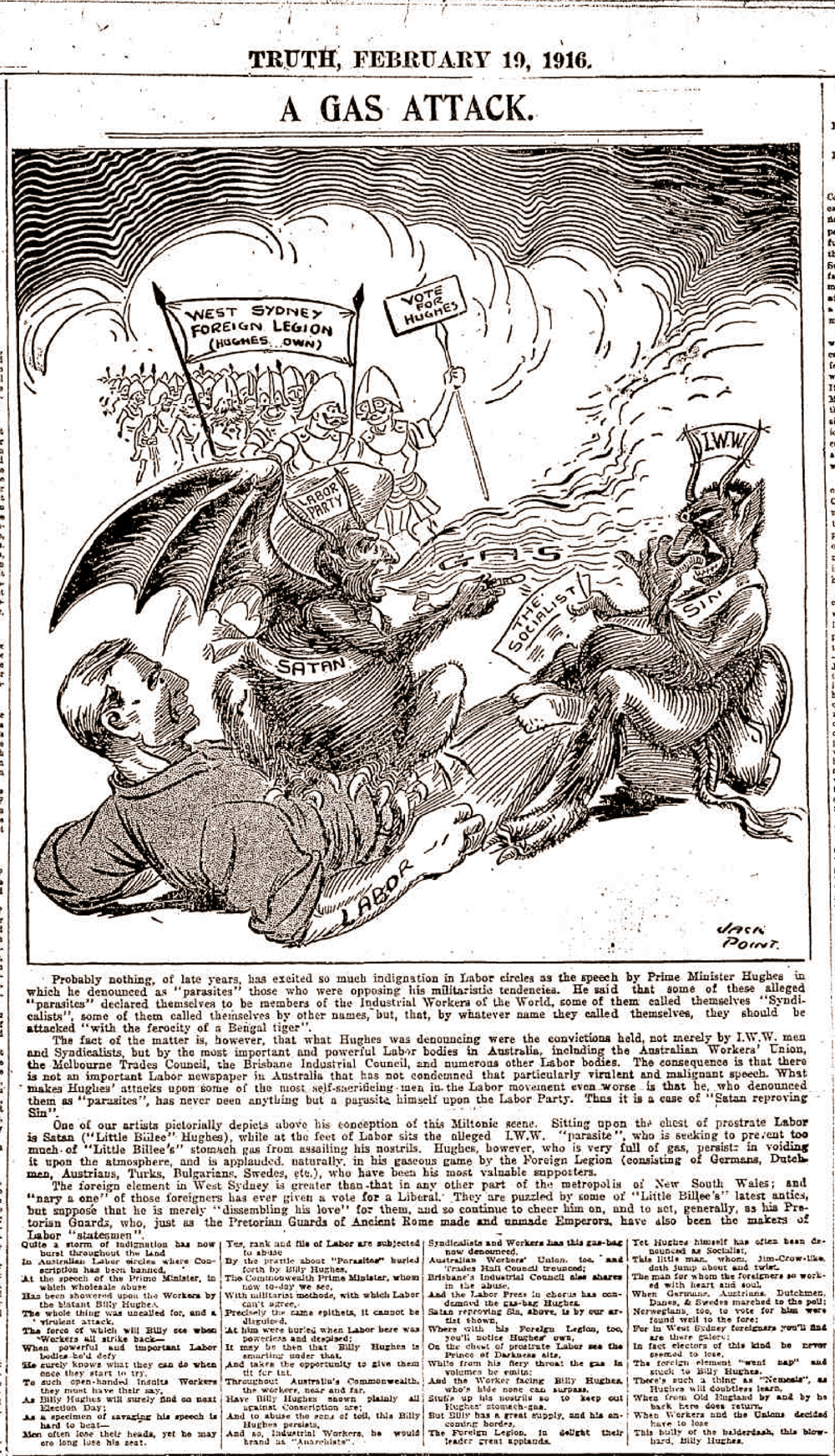

In Sydney members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, often referred to as the 'Wobblies') also firmly opposed the war. They did not go silent when it began. Rather they held a meeting in the Domain on the Sunday after the outbreak (9 August) where they unfurled a banner on which was inscribed 'War! What for?' [14] Like Boote and other active socialists, the IWW generally disregarded the War Precautions Act and the censor, and agitators openly sold literature in Sydney in defiance of the law. Indeed, the IWW played a central role in general anti-war agitation and in the campaigns against conscription. The war presented the IWW with a dramatic opportunity to demonstrate the extent to which this was a capitalist war and that capitalist society was totally dependent on its working class to provide recruits for its army. To illustrate this point, the IWW showed that the numbers of enlistments from the Australian Workers Union represented 20 per cent of its members whereas enlistments from the NSW Parliament represented two percent and likewise two percent for the Sydney Chamber of Commerce. [15]

[media]Their most effective attack against the war was its cost; both in terms of lives and the huge profits corporations and capitalists were amassing from it. Despite warnings from the police not to criticise the war or propagate anything that might be harmful to the war effort, they continued to denounce the war at Speakers Corner and in their club rooms on Sussex Street. Accordingly, the Sydney police became 'unusually diligent in prosecuting Wobblies for uttering inflammatory and seditious words in the Domain.' [16] Donald McLennan Grant was an active and popular speaker who regularly drew record crowds to the Domain on Sundays. He passionately urged men not to enlist for the war or for any voting adult to support conscription. In 1916 he was dismissed from his job for his anti-war activities and was later gaoled as one of the 'Sydney Twelve' in the same [media]year. [17] [media]In September 1915, Tom Barker, one of the IWW's most effective public agitators was fined £100 for publishing an anti-recruiting poster. [media]In May 1916 he was sentenced to 12 months hard labour in gaol under the War Precautions Act for publishing a Syd Nicholls anti-war cartoon. [18] The Australian Government would later deport Barker to Chile for his political activism. [19]

Despite this severe repression, the IWW paper Direct Action became a popular publication for readers wishing to 'escape the overwhelmingly pro-war stance of the major' dailies. It also appealed to others who were looking for reasons to justify an anti-war attitude in a climate where jingoistic patriotism and loyalty was both expected and demanded from the population. [20] By 1916, despite the fact that the police department in Sydney had banned the sale of anti-war papers in public (on the grounds that their distribution promoted public dissent), Direct Action had a circulation of approximately 16,000 copies per week, a number which, in estimating readership, can probably be doubled or trebled. [21] During the days leading up to the conscription referendums their headlines were blunt and to the point: 'Single Men to the Front: The Bludgeoning of Bachelors', 'Compulsion; The Cackle of the Conscriptionists', 'The Call for the Blood of Bachelors'. [22]

Vehemently opposed to conscription and 'the advocates of the organisation of murder,' Direct Action upheld the individual's right to liberty and freedom of speech and action which conscription threatened to take away. As the pro-war and conscription supporters increasingly rallied for freedom and liberty in Europe, the irony of Australians at home losing their freedom and liberty to think and act, publish and protest was not lost on the paper. In an article published in May 1916, 'Ajax' wrote:

The attempts to muzzle the press, stifle free speech and bludgeon individuals whose ideas do not harmonise with militarist-maniacs makes it obvious that we require more liberty here, without going 12,000 miles to fight for it. [23]

Frank Anstey, the most outspoken anti-war and anti-censorship member of the House of Representatives, made a similar point at an anti-conscription meeting at the Sydney Town Hall on Friday 22 September 1916. As he asked his crowded audience, 'What is the good of victory abroad if it only gives us slavery at home?' [24]

Direct Action summed up its extensive anti-war activities itself on 24 February 1917:

As for propaganda, not alone against conscription, but also against the war, the IWW held 120 Sunday afternoon Domain meetings, 240 hall lectures and over 300 outdoor street meetings in the vicinity of Sydney between August 1914 and October 28th 1916. We sold over 1000 copies of Kirkpatrick's 'War, What For' and over 2000 pounds of revolutionary literature as well as sales of Direct Action. [25]

[media]Many who supported the war and conscription – most politicians, the mainstream press, the pulpit and especially the Prime Minister, saw in the IWW everything that was in need of suppression during the war years. They needed to be silenced yet charging them under the Wartime Precautions Act was no longer enough. They had to be seen as the violent and dangerous revolutionaries that their opponents believed them to be. In September 1916, 12 leading Sydney members of the IWW were charged with forgery, felony, conspiracy, arson and treason. The trial aimed at silencing and removing their anti-war and anti-conscription voices from the public domain. All 12 were found guilty on some or all of the charges and received prison sentences of between five and 15 years.

[media]Late in 1916 Henry Boote became convinced that the 12 men had been persecuted in a serious miscarriage of justice and he began to champion their cause. He thoroughly researched the facts and used the pages of The Worker to argue his case. On 7 December, 1916, his article 'Guilty or Not Guilty?' was published in The Worker. [26] In it he declared that the referendum campaign had served the government's purpose to blacken the anti-conscriptionists with IWW criminality. Once the two were connected, the 'Sydney Twelve' had no chance of justice. He further fulminated that their sentences were 'a grave judicial scandal'. His sustained agitation in the face of hostile opposition from the authorities eventually led to a Royal Commission enquiry in 1920, after which the twelve were gradually freed. [27]

Further repressive legislation followed the sentencing of the 'Sydney Twelve'. In December 1916, The Unlawful Associations Bill was introduced and passed in both Houses. It declared the IWW to be an unlawful association and any member of it who actively opposed the war was to be imprisoned for six months. Any foreign born member who advocated the hindering of the war effort was to be deported. [28] Despite this repressive and draconian act, IWW anti-war agitation continued throughout the first half of 1917. In July of that year the government amended the Unlawful Associations Act so that members of the IWW had one month to renounce their membership; failure to do so would lead to six months in jail. They also had to prove they had been born in Australia to avoid being deported. [29] The amended Act also provided six months jail for printing and distributing IWW material and prohibited its transmission through the post. In September 1917, 75 members of the IWW were prosecuted. Most received six months imprisonment with hard labour. In total, 103 members were sentenced and of these, approximately 30 were deported. [30]

This was a ruthless and authoritarian suppression of a small group whose members probably only ever numbered a few thousand. [31] By the close of 1917, the IWW movement in Sydney had largely been suppressed, its leaders in gaol or deported, and Direct Action had ceased publication. Yet the IWW had generated many sympathisers. It was

…the very success of its anti-war propaganda that led to the IWW becoming the object of this combined assault at state and commonwealth level. Enlistment was decreasing every week and people's attention was focussing more on the cost of living increases caused by the war. The IWW anti-war propaganda fell on receptive ears. [32]

Indeed, their militant vigour in opposing conscription and their claim that the working classes were mere cannon fodder for the imperialist war machine from which they would not benefit, did appeal to many Sydneysiders. By the end of 1917, many residents were struggling financially and were emotionally exhausted. The spectre of returned soldiers on the streets, many of them wounded, ragged, unemployed and often homeless, was a daily reminder to many that there was indeed little glory in this war. [33]

Peace at last?

[media]On the morning of Friday 8 November 1918, news reached Sydney that the armistice had been signed. It was in fact a false alarm, however, by midday the streets of the city were thronged with people singing and cheering. The celebrations continued throughout the weekend and, when the news finally arrived on the evening of Monday 11 November that the Germans had signed an armistice, thousands of Sydneysiders streamed into Martin Place to publicly celebrate the end of the war. The party lasted unabated for the next few days as people young and old, bosses and workers united to rejoice in their collective relief and to release their shared grief. According to The Sydney Morning Herald:

suddenly…everyone who could walk turned an eager face towards the city. Never in the history of Sydney did a greater flood of passengers flow over the evening service of trams, trains and ferries…Every man, woman and child came into the city to 'celebrate', but they came in such numbers that they defeated their own purpose. At 9 o'clock, in Martin Place and Moore Street, and in Pitt and George Streets adjoining, the crowds were so dense that no one could move. They could only stand and cheer.' [34]

[media]The acting Prime Minister, William Alexander Watt, released a statement in which he spoke for all Australians: 'There will go up from the hearts of the people of Australia a great sigh of relief that the dawn has come'. [35] After the great sigh of relief, many people hoped that life would go back to 'normal' pre-war conditions and that the deep divisions and social conflicts, which the strain of war had caused would now abate. Surely peace in Europe would bring peace in Australian society? Yet the war had challenged and changed society greatly and the post-war world would bring new struggles to Sydney. [36]

Bitter divisions and resentments festered between those who 'had gone' and those who had 'shirked' and stayed at home, between those who had supported conscription and those who had not. Society remained for a long time split between those 'loyal' to Britain and Empire and those who 'believed in Australia first'. Tensions between Catholics and Protestants continued; so too did anti-German sentiment. By September 1919, thousands of 'enemy aliens' who had been interned during the war were not reintegrated back into civil society but were instead forcibly deported. The IWW had been crushed but the post-war years saw a new revolutionary class 'threat' in the guise of communism.

[media]In Sydney, returned soldiers needed jobs yet the journey back to civilian and domestic life would not be easy for some; jobs were scarce and employers were often reluctant to replace well-trained men for ex-soldiers. Injured soldiers required hospital beds and medical care; wounds might be healed but some of the survivors would stay in bed for the rest of their lives. For many men, limbs and sight had been lost; for others their minds had been permanently shattered. Relationships between the sexes changed too as returned soldiers, some of whom came back as strangers to loved ones, sought comfort in the mateship offered by the newly established Returned Soldiers and Sailors Imperial League of Australia (now simply called RSL) clubs rather than in the arms of their wives. Women too had to readjust to the return of the men after years of living independently and controlling their households autonomously. Many struggled 'to go back to normal' and indeed, the divorce rate grew rapidly from 879 in 1919 to 1,536 by 1924 as the personal and financial strains of the post-war years took their toll. [37]

Perhaps the most immediate and jarring effect at the end of the war was the stark, cold fact that Australia had lost more than 61,000 men killed on the battlefield and another 160,000 men who returned wounded. Every suburb had lost young men in the prime of their lives; men, who as Mary Gilmore lamented, who were 'so young' and who would have made a lasting and enduring contribution to post-war Australia. In the final analysis, that is a personal and familial, yet also local and national legacy that in 1918, as it still is today, was quite simply incalculable.

References

John Barrett, Falling In: Australians and 'Boy Conscription' 1911–1915 (Sydney: Hale and Iremonger, 1979)

Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 2013)

James Bennett, Rats and Revolutionaries: The Labour Movement in Australia and New Zealand 1890–1940 (Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press, 2004)

Verity Burgmann and Jenny Lee (eds), Staining the Wattle: A People's History of Australia since 1788 (Fitzroy, Vic: McPhee Gribble, 1988)

Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993)

Charles Manning Hope Clark, New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, vol 6, A History of Australia (London; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987)

Joy Damousi and Marilyn Lake (eds) Gender and War: Australians at War in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge, UK; New York; Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Eric Fry (ed), Rebels and Radicals (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1983)

Mrs Septimus Harwood, 'The Peace Society: Its Origins, Work, Difficulties and Mistakes' (paper read at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Peace Society, NSW Branch, Royal Society Hall, Elizabeth Street, Sydney December 13, 1921)

John F Hill, 'Vigour', Child Conscription, Our Country's Shame (Adelaide: Burmeister and Co, 1912)

Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968)

Marilyn Lake, Mark McKenna and Henry Reynolds, What's Wrong With Anzac? The Militarisation of Australian History (Sydney: UNSW Press, 2010)

Michael McKernan, Australian Churches at War: Attitudes and Activities of the Major Churches 1914–1918 (Sydney and Canberra: Catholic Theological Faculty and Australian War Memorial, 1980)

Michael McKernan, The Australian People and the Great War (Sydney: Collins, 1980)

Eleanor M Moore, The Quest for Peace: As I Have Known It In Australia (Melbourne: Wilke and Co Ltd, 1948–49)

The Peace Society, Pax: The Monthly Organ of the Peace Society

Australian Workers' Union, The Worker

Sydney Labour History Group, What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History (North Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 1982)

Notes

[1] Ajax, 'Compulsion: The Cackle of the Conscriptionists,' Direct Action (13 May, 1916): 3

[2] According to Jauncey, Boote and The Worker '…can definitely be set down as factors in the defeat of conscription in Australia'. Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 223

[3] Quoted in Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 281

[4] Sydney Morning Herald, 11 December, 1917, 4

[5] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 223

[6] See James Bennett, Rats and Revolutionaries: The Labour Movement in Australia and New Zealand 1890–1940 (Dunedin, New Zealand: University of Otago Press, 2004), 73–78

[7] Henry Earnest Boote, '22 December, 1917,' Sidelights on Two Referendums 1916–1917: Extracts from Letters to Brother Will, Mary E Lloyd (ed) (Sydney: William Brooks and Co, 1952), 87. Henry Stead was greatly interested in the New Zealand position and published a summary of the Act in Stead's Review on 26 August 1916. He later published a pamphlet entitled 'Conscription in New Zealand' to further enlighten the Australian public. After the War, a Royal Commission was established in New Zealand to investigate the treatment of conscientious objectors. Following the publication of this report, Stead issued another pamphlet, 'The Tragic Fate of the Conscientious Objectors. A Disgrace to British Civilization.' In this he exposed the many men who had been tortured and imprisoned by the British and New Zealand Governments.

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 July, 1916, 11

[9] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 215

[10] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 312

[11] In October 1917, Miles established the Advance Australia League under the slogan 'Australia First'. See his anti-conscription pamphlet, William John Miles, Australian Conscription for Service Abroad Unnecessary and Unjust. A Reply to the Prime Minister (Melbourne: Fraser and Jenkinson, 1916)

[12] The Peace Society of New South Wales referred to conscription as the 'enslavement of conscience'. See The Peace Society of New South Wales, Ninth Annual Report (November, 1916): 6

[13] As Eleanor Moore noted in The Quest for Peace written in 1948–49, 'The national verdict against conscription kept Australian records clean from such hideous persecution of conscientious objectors to military service as disgraced the annals of New Zealand, Great Britain and the United States of America, in all of which conscription was imposed by proclamation.' See Eleanor M Moore, The Quest for Peace: As I Have Known It In Australia (Melbourne: Wilke and Co Ltd, 1948–49), 37. See also Hugh Smith, 'Conscientious Objection to Particular Wars: The Australian Approach' (working paper no 116, The Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1986)

[14] Quoted in Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968), 105

[15] 'The Patriots', Direct Action, (1 August, 1916) quoted in Cain See Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 184

[16] Verity Burgmann, 'The Iron Heel The Suppression of the IWW during World War 1' in Sydney Labour History Group, What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History (North Sydney: George Allen and Unwin,1982), 176

[17] Frank Farrell, 'Grant, Donald McLennan (Don) (1888–1970),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/grant-donald-mclennan-don-6453/text11047, published in hardcopy 1983, viewed 27 February 2014

[18] Verity Burgmann, 'The Iron Heel: The Suppression of the IWW During World War 1,' in Sydney Labour History Group, What Rough Beast? The State and Social Order in Australian History (Sydney: George, Allen and Unwin, 1982),174; Lindsay Foyle, 'Nicholls, Sydney Wentworth (Syd) (1896–1977),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/nicholls-sydney-wentworth-syd-11235/text20035, published in hardcopy 2000, viewed 27 February 2014

[19] See Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 265–272; Eric Fry, 'Barker, Tom (1887–1970),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/barker-tom-5131/text8583, published in hardcopy 1979, viewed 27 February 2014

[20] Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 189

[21] Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 227

[22] Direct Action, Tuesday 1 June 1915, 3; Saturday 13 May 1916, 3; Saturday 23 September 1916, 4

[23] Ajax, 'Compulsion: The Cackle of the Conscriptionists', Direct Action, 13 May 1916, 3

[24] Quoted in Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 183. See also Ian Turner, 'Anstey, Francis George (Frank) (1865–1940),' Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/anstey-francis-george-frank-5038/text8367, published in hardcopy 1979, viewed 27 February 2014

[25] 'Spasms,' Direct Action (24 February, 1917): 4

[26] Ian Turner, Sydney's Burning (Sydney: Alpha Books, 196): 60–67

[27] Turner, (1967), op. cited, 232-50; According to Robson it was 'a measure of the search for scapegoats during the industrial and psychological upheaval of the war that justice had gone so far astray'. L.L. Robson, Australia and the Great War 1914–18, op. cited, (1969), 21

[28] See Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 251–56

[29] Many members were indeed arrested and jailed or deported For the story of the deportations of IWW members, see Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 262–72

[30] Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 265

[31] Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 290

[32] Frank Cain, The Wobblies at War: A History of the IWW and the Great War in Australia (Victoria: Spectrum Publications, 1993), 201

[33] As Jauncey notes, '…thoughtful people could see that not much stock could be placed in the lavish promises that militarists and their supporters made to men enlisting. Up to the end of the 1917, 46,672 men had returned to Australia, of whom 37,230 had been discharged. So far repatriation schemes had only affected 3,252 men with £153,000 spent. These facts had their effect on the conscription campaign, and certainly did not tend to increase confidence in Australia's militarists or their promises.' Leslie Cyril Jauncey, The Story of Conscription in Australia (London: Allen and Unwin, 1935; reissued Melbourne: MacMillan, 1968) 314–15

[34] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November, 1918, 6

[35] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 November, 1918, 6

[36] Not least the Spanish influenza which came to Australia in 1919 and brought misery and death to thousands and 'in Sydney alone, almost 40 per cent of the population contracted' it in 1919. See Joan Beaumont, Broken Nation: Australians in the Great War (Sydney: George Allen and Unwin, 2013), 523

[37] Michael McKernan, The Australian People and the Great War (Sydney: Collins, 1980), 222

.