The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Bulletin

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Bulletin

[media]The Bulletin, Australia's longest-running magazine, would surely be on any short-list of controversial Sydney publications. On its masthead, from the first issue until the early 1960s, was the clarion cry 'Australia for the White Man', a statement that ignored the original inhabitants of the continent, from whom the 'white man' had wrested it, as well as the many non-white immigrants who had come to Sydney.

The Bulletin was [media]founded in January 1880, established by journalist Jules François (born and baptised John Feltham) Archibald, and journalist and politician John Haynes. They 'had about £140, which they used to buy a small case of battered display type, put a deposit on a second-hand press and rent the Scandinavian Hall at 107 Castlereagh Street'. [1] Initially Haynes sold advertising while Archibald gathered copy, wrote and subedited.

There had been some dispute about the title of their new publication: Haynes wanted the Tribune, while Archibald favoured the Lone Hand; they settled for naming the paper after San Francisco's Bulletin.[2] It was intended to be a journal of political and business commentary, with some literary content, and the first issue appeared on 31 January 1880, costing fourpence, and its stories of the hangings of Captain Moonlite and the Wantabadgery bushrangers grabbed readers' attention – its 3,000 copies soon sold out. Success followed and circulation built to 15,000 within 18 months, reaching 80,000 by 1900.

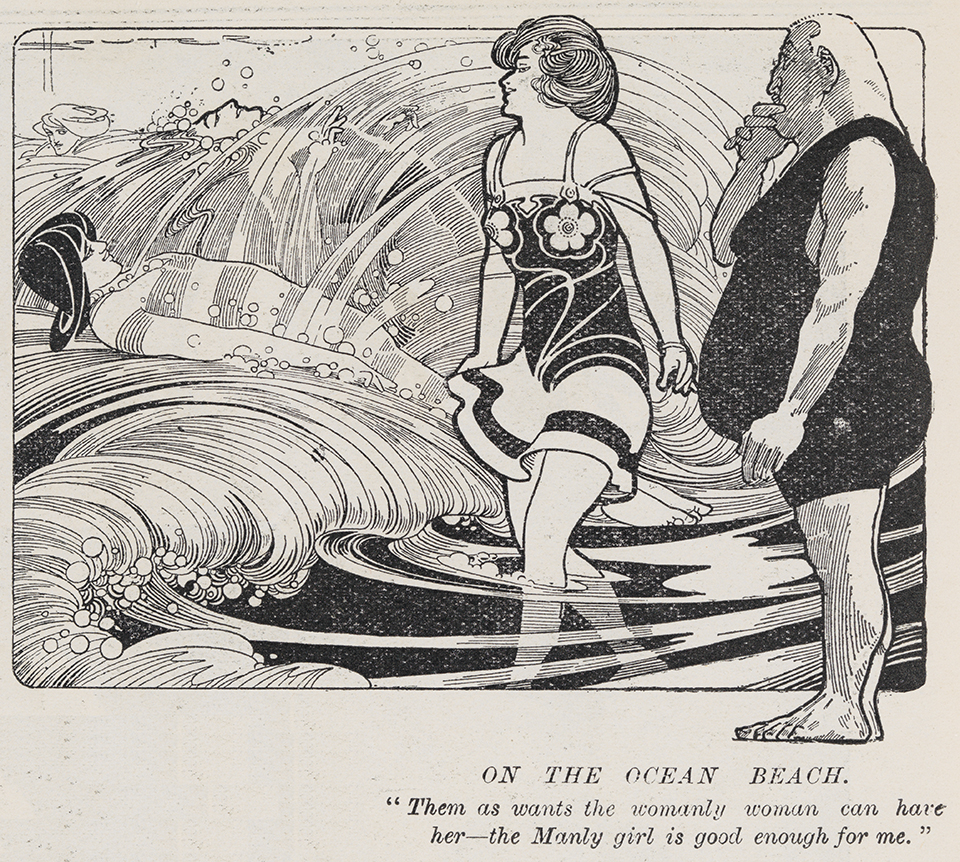

The Bulletin has been described [media]as 'racist, isolationist, protectionist and "masculine"'. [3] It certainly tapped into a vein of something very Australian. It gave its readers a perspective they weren't getting in their newspapers, which usually drew their inspiration from 'home' – Britain.

Though it was a Sydney publication, it quickly earned the title of the 'bushman's bible', and was a conduit connecting the cities of Australia with rural communities, thereby facilitating the emergence of bush poetry as a popular cultural artefact throughout the continent. Even though the Bulletin's poetry covered stories from all walks of life, the romantic portrayal of rural life was one of its strengths. In pre-Federation Australia, this was critical in defining a romanticised version of 'Australianness'.

From 1886, Archibald opened the magazine up to contributions from its readers, and this led to a flow of poetry, short stories and cartoons from all over Australia, contributed by miners, shearers and timber-workers, as well as urban dwellers. Some of this material was of high quality, and over the years many of Australia's leading literary lights had their start in the Bulletin's pages: it was here that The Man from Snowy River first appeared. It was the Bulletin's literary editor, Alfred Stephens, who was a guiding force in creating the magazine's literary reputation, including the so-called ' Bulletin school'. Its 'Red Page' on page 2 was a page of literary gossip and opinions, and was widely read, even until late in the twentieth century. At the same time, the Bulletin ran well-informed political and business news.

The Bulletin gave an Australian perspective on everything – on society, events and politics – and it was noted for its larrikin spirit. Its view on the plague in Sydney in 1900, which engendered panic and hysteria, allowed it to have a swipe at a few sacred cows:

So far the Plague...is a very small affair. It isn't a patch on the daily, hourly typhoid as a means of slaughtering the public, and so far it has proved about as safe as football, and much safer than it was a few weeks ago to have doubts concerning the absolute justice of the war in South Africa. [4]

[media]But it wasn't just what the Bulletin wrote about or the slant that it took – it was also who was doing the writing and illustrating. Over its long history, the magazine published virtually every major Australian author and 'black-and-white' artist; this was a time when cheap colour reproduction was not possible. Its contributors list reads like a Who's Who of Australian art, literature, and economic and political commentary. Early contributors included writers such as AB (Banjo) Paterson, Henry Lawson and Miles Franklin, poet Victor Daley, and cartoonists Phil May, David Low and Livingston (Hop) Hopkins.

Among the artists, the Lindsay brothers had a strong association with the Bulletin. Norman Lindsay was lured to Sydney by Archibald, after John Elkington, a friend of the Lindsay brothers from Melbourne who was attracted to the Bulletin's style of nationalism, showed some of Norman's Decameron drawings to Alfred Stephens, who described them in the Bulletin as 'the finest example of pen-draughtsmanship of their kind yet produced in this country'. [5] Archibald offered Norman a job, and in May 1901 Norman visited Sydney and accepted Archibald's offer of £6 a week to join the Bulletin as a staff artist providing cartoons, decorations and illustrations for jokes and stories. The association was to last, with a few breaks, for over 50 years. More than any other artist, Norman Lindsay gave visual definition to the Bulletin's editorial policy, particularly its nationalism and racism – Aborigines invariably figured as comics, Jews as old-clothes dealers with hooked noses. [6] Norman's brother Lionel returned to Australia from Europe early in 1903, and Banjo Paterson offered him a job as a cartoonist for £4 per week with the right to contribute illustrations to the Bulletin. He soon became a freelance illustrator for the magazine, and his brother Percy Lindsay also saw his illustrations appear in the Bulletin.

As its masthead statement implied, it wasn't shy of controversies. It was political from the outset, but after Archibald retired in 1907 the Bulletin became steadily more conservative. This marked its break with the political left and perhaps the end of its significant political influence, since by World War I it had become openly 'Empire-loyalist'. In 1916–17 the paper supported conscription and Prime Minister WM (Billy) Hughes at a time when Australia's involvement in a war – derided in some quarters as 'an imperialist war' – divided the nation.

Between the wars, the magazine steadily declined, in influence and circulation. Its admiration of the bushman was anachronistic as Australia became highly urbanised. Share sales led to the Prior family owning the Bulletin from the 1920s, and by the 1940s the Bulletin was regarded as a relic of past times, notable for extremely right-wing politics complete with anti-Semitism and racism. Yet it still retained its place in Australian literary life well into the twentieth century.

By the late 1950s, still 'radically' conservative and losing money, it was seen as a virtual basket case. But in 1961 it was sold to Australian Consolidated Press (ACP), whose owner, Sir Frank Packer, had an eye for media opportunities. He appointed Donald Horne editor, and the racist statement 'Australia for the White Man' disappeared. Despite its declining reputation and revenues, Sir Frank Packer, and later his son Kerry Packer, were prepared to subsidise the magazine, as it had a cachet that the other magazines of the ACP stable, including the Women 's Weekly, didn't have. The Bulletin remained politically conservative, but rejoined the political and journalistic mainstream, as a well-edited magazine of political and business news and commentary, with forays into literature as a gesture to its past.

Not all these forays were successful. In 1961, the poet Gwen Harwood sent two sonnets into the Bulletin, under the name of Walter Lehmann, an 'apple orchardist in the Huon Valley in Tasmania, and husband and father'. Horne published the poems, to his later embarrassment when it was revealed that, read acrostically, the sonnets read 'So Long Bulletin' and 'Fuck All Editors'. Harwood believed that the sonnets were 'poetical rubbish and [would] show up the incompetence of anyone who publishe[d] them '. [7]

In its last years as part of the Packer stable, the Bulletin had something of a resurgence, as ACP invested more heavily in it, attracting Sydney writers of the calibre of Peter Carey, Les Carlyon, Paul Toohey, Tim Flannery and Maxine McKew. Its last edition featured lengthy articles by Tom Keneally, Frank Moorhouse and Richard Flanagan.

Stories about the Bulletin abound. One of the better ones is as follows:

former Prime Minister Paul Keating loathed the Bulletin. On one occasion, he sent a stinging – but brilliantly written – letter to the editor Garry Linnell, claiming that he found the publication 'rivettingly mediocre'. Linnell not only published the letter, but promoted the fact that 'Paul Keating Writes for Us'. He then awarded the Letter of the Week to Paul Keating, Potts Point, NSW, and for Keating the problem was the prize – a year's subscription to the Bulletin! To Keating's great fury, for the next 12 months a copy of the Bulletin would arrive in his mailbox every Wednesday morning. [8]

The magazine's twentieth-century peak came in the early 1990s, when editor David Dale took circulation to more than 100,000. But the era of news magazines was in decline – partly economics, partly falling victim to the power of the internet. The magazine, with a Wednesday publication date, seemed expensive compared to fat Saturday newspapers, and free commentary on the internet.

In its last years, the Bulletin had about 35,000 subscribers, and if it had a strong cover that attracted publicity, its sales at news stands might reach 20,000, well down from the level of the mid-1990s. By the early years of the twenty-first century, it had fallen on hard times – or the times had moved on – and in the end the Bulletin was overtaken by history. A controlling share in the Packers' company PBL was bought by a foreign-based company, CVC Asia Pacific in 2007, and within a year the closure of the Bulletin was announced. While acknowledging the magazine's long history and recent editorial successes, CVC Asia Pacific said that despite the best efforts of management, the magazine was no longer commercially viable. The Bulletin closed in January 2008, after 128 years of continuous publication.

References

The Bulletin Centenary: 1880–1980 Souvenir Edition, Australian Consolidated Press, Sydney, 1980

Sylvia Lawson, The Archibald Paradox, A strange case of authorship, Allen Lane, Ringwood, Victoria, 1983

Sylvia Lawson, 'Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919'), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

John Lyons, 'Foreign buyers silence the Bulletin', Australian, 25 January 2008, at http://www.news.com.au/national/foreign-buyers-silence-the-bulletin/story-e6frfkvr-1111115393821, viewed 26 August 2010

Patricia Rolfe, The Journalistic Javelin; an Illustrated History of the Bulletin, Wildcat Press, Sydney, 1979

Notes

[1] Sylvia Lawson, 'Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919'), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3 Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[2] Sylvia Lawson, 'Archibald, Jules François (1856–1919'), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 3 Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1969, pp 43–48, available online at http://adbonline.anu.edu.au/biogs/A030046b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[3] Mark McKenna, the captive republic: a history of republicanism in Australia, 1788–1996, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, 1996, p 153

[4] Bulletin, 31 March 1900, p 6

[5] Bernard Smith, 'Lindsay, Norman Alfred Williams (1879–1969)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 106-115, available online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100676b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[6] Bernard Smith, 'Lindsay, Norman Alfred Williams (1879–1969)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 10, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1986, pp 106-115, available online at http://www.adb.online.anu.edu.au/biogs/A100676b.htm, viewed 28 October 2010

[7] Cassandra Atherton, '"Fuck All Editors": The Ern Malley Affair and Gwen Harwood's Bulletin Scandal', Jumping the Queue: Journal of Australian Studies, no 72, 2002, available online at http://www.api-network.com/main/pdf/scholars/jas72_atherton.pdf, viewed 28 October 2010

[8] John Lyons, 'Foreign buyers silence the Bulletin', Australian, 25 January 2008, at http://www.news.com.au/national/foreign-buyers-silence-the-bulletin/story-e6frfkvr-1111115393821, viewed 26 August 2010

.