The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The Prout's Bridge Incident

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The Prout’s Bridge Incident

In 1853, the year before the events of the Eureka Stockade at Ballarat in the Victorian goldfields, Canterbury had its own protest against perceived injustice when John Chard was involved in a dispute with Cornelius Prout at the bridge over the Cooks River at Canterbury.

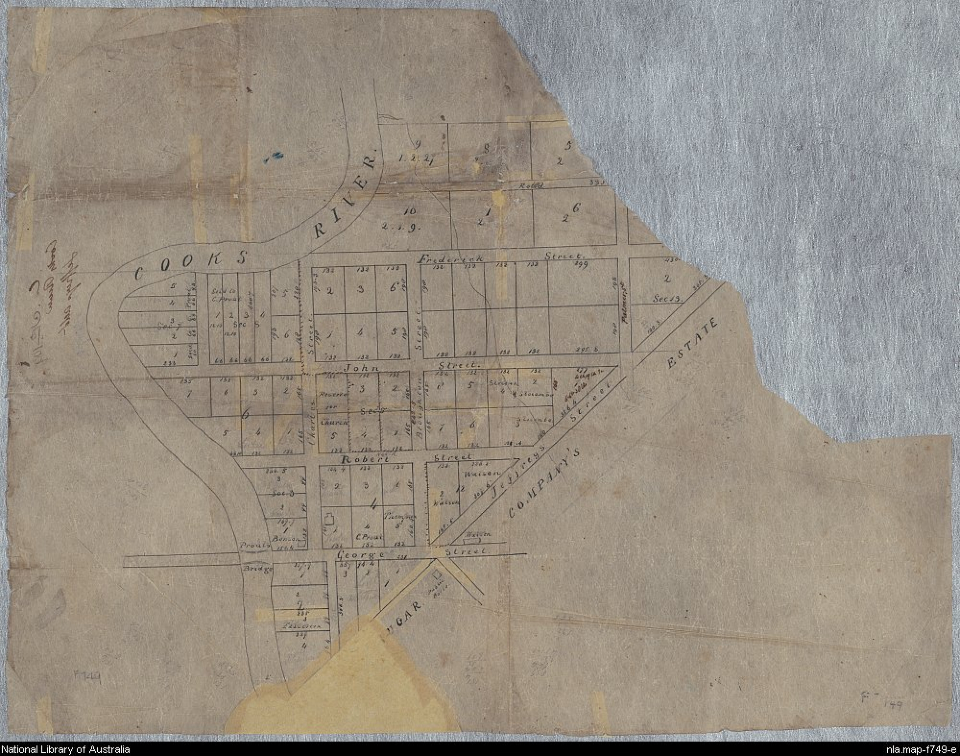

In 1833, the under-sheriff of Sydney, Cornelius Prout, who [media]had a farm on the south side of the Cooks River opposite the present racecourse, commenced a punt across the river at Canterbury. Although this was said to save six miles (9.6 kilometres) on the journey to and from Sydney via the Punch Bowl (now the Punchbowl Road and Georges River Road intersection near Coronation Parade at Belfield), the cost of one shilling (10 cents) would have been very high for the market gardeners, sawyers and charcoal burners of the area between the Cooks and Georges rivers.

In 1839, Prout and Robert Campbell agreed to a public road (now Canterbury Road) through their properties, provided Prout built a bridge. To raise the money to build the bridge, Prout asked for a donation from all the local landowners, using convicts for the stonework and carpentry. The bridge opened in November 1841, and for six weeks the crossing was free. Then a gate appeared with a notice announcing the bridge had cost £200, subscriptions had raised only £80, and a toll would be paid by all users (other than the subscribers) until the remaining £120 had been raised.

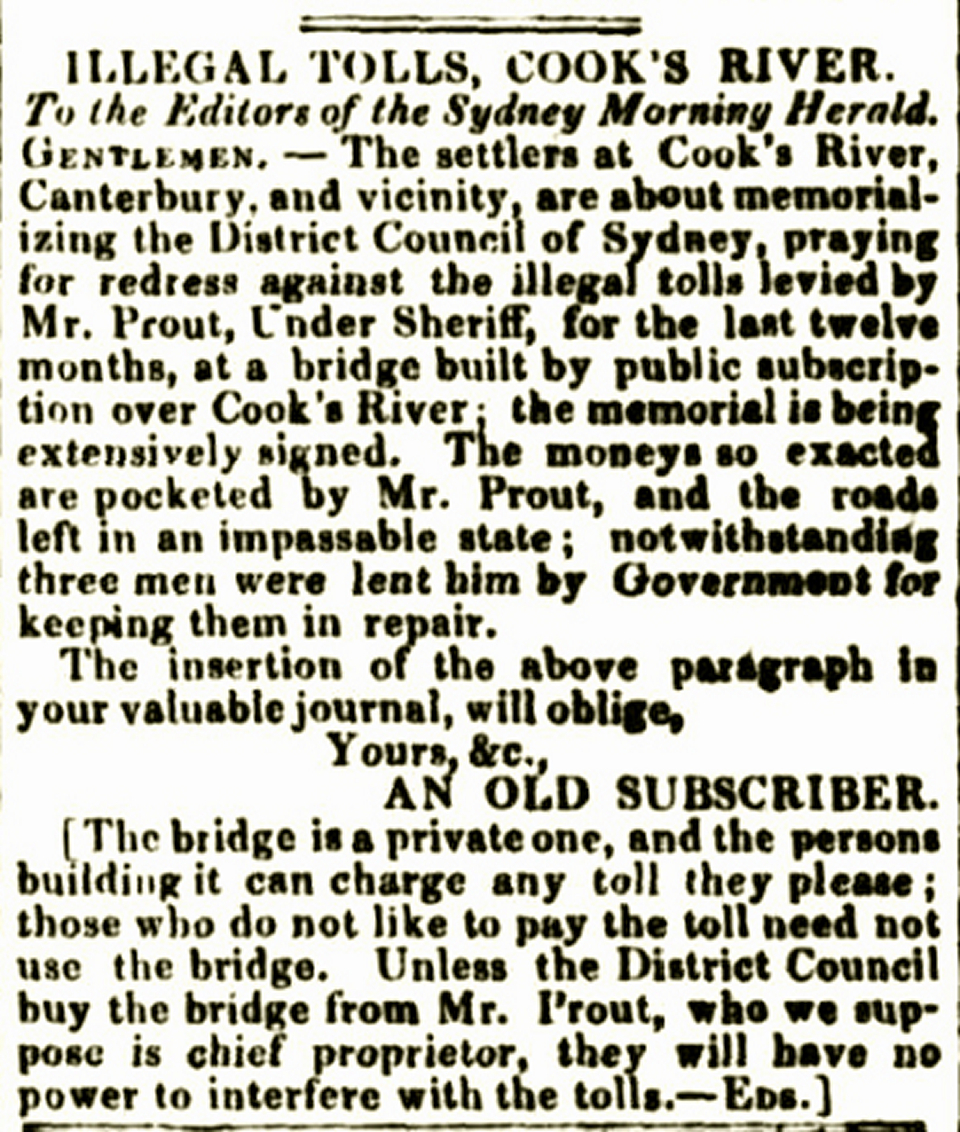

[media]As early as 1843, there was a complaint in The Sydney Morning Herald about the toll of threepence on the bridge, claiming that it was illegal and that the money was being pocketed by Prout. [1]

In 1849, the trustees of Cooks River Road (now the Princes Highway) petitioned the governor to declare a 'new line of road to Canterbury' (now New Canterbury Road) as an alternative to the old Canterbury Road, and the prospect of this road gave hope of government sympathy to the residents opposed to the toll.

[media]An anonymous group hired solicitors to write to the colonial secretary, saying that Prout had long since been repaid with interest for his outlay, and that if a toll was to continue it should be spent on keeping the road in repair. The government agreed that Prout was demanding the toll illegally but refused to take action, saying that the residents should take their own action at law.

In 1851, George Davis, son-in-law of John Chard, who had given the land for the Wesleyan Chapel and cemetery at Moorfields, attempted to pass through the tollgate without paying the toll. He was charged and fined five shillings, plus payment for damages and legal costs.

In August 1853, Prout announced that from 5 September the road through his estate south of the river would be closed to the public. A public meeting was called at the Canterbury Arms Inn at Canterbury, and a committee was formed to fight the closure. The official spokesman was Frederick Lee of The Hermitage, Kingsgrove, a Sydney merchant and landowner.

On 5 September, Prout locked the gate as promised. John Chard arrived on his cart and asked to be allowed through. He was refused and pushed Prout aside, then used his axe to knock the hasp off the gate, and chopped the bars of the gate down. He then put on his coat, got into his cart and went through.

The next day, Prout persuaded a police magistrate to issue a warrant for arrest, and the police arrived at Chard’s house 'in a remote part of the bush' at 11 o’clock at night, after it was claimed they had spent 'some hours, in company with Prout’s son' at Prout’s public house, the Sugar Loaf Inn at Canterbury. The police burst open Chard’s door, handcuffed him and hauled him to the Sydney watchhouse. [2]

[media]The case for the defence was that the gate and tollhouse were built on Crown land on the banks of the river with government (that is, convict) labour and Prout had no right to claim ownership, that Prout had been repaid at the rate of over £200 a year, about twenty times his original outlay, and that Prout had promised before witnesses over and over again to open the road as soon as he had recovered his expenses.

The charges against Chard were of trespass and wilful damage, and when the case was heard on 25 November 1853, Prout’s case could not be shaken. The road was not a public highway and Chard was found guilty. The only way the judge and jury could show where their real sympathies lay was in the damages they levied – one shilling.

Editorials in Sydney newspapers supported Chard and savaged Prout. [3] A protest petition was available in the three inns in Canterbury (including the one owned by Prout) and in 'the Man of Kent, in the Forest’ (present-day Kingsgrove), and a deputation of Frederick Lee and two members of the Legislative Council presented the petition with 165 signatures to the governor general on 14 December. An appeal was heard on 20 December, but the original verdict was upheld.

The government decided to declare the road a parish road but there were months of delay, much to the annoyance of Frederick Lee who wrote many letters asking for action. [4] It was finally gazetted in April 1855.

Prout continued to charge a toll throughout 1854 and, although he died on 19 February 1855, the toll continued until, at the instigation of Frederick Lee, the government took action against the tollkeepers in the Supreme Court in June 1855.

[media]In the period between the road being gazetted in April 1855 and the action in the Supreme Court, it was found that the toll averaged over £2 per week [5]. With an average annual collection of £100 per year for 13 years, the complaints by the residents about Prout seem justified.

The executor of Prout’s estate claimed compensation for the resumption of Prout’s Bridge, but the government decided that the claim was not sustained [6].

It is ironic that the citizens of Canterbury, having won the fight to cross the Cooks River bridge without paying a toll, found that the next year the new trustees of the Canterbury Road applied to charge a toll for the upkeep of the road. However, the residents, through their trustees, had won the right to control the revenue rather than have it go into the pocket of one of the gentry.

References

Lesley Muir, A Wild and Godless Place: Canterbury, 1788–1895, Master of Arts Thesis, University of Sydney, 1984

New South Wales Legislative Council, 'Prout v Chard', Votes and Proceedings, vol 2, Sydney, 1853

Bell's Life in Sydney and Sporting Reviewer, 1845–1860, George Ferrers Pickering and Charles Hamilton Nicholas, Sydney, NSW

Michael Fitzpatrick, Clerk of the Executive Council, 4 October 1855, State Records Authority of New South Wales, AO 4/3295, file 55/10804

Notes

[1] The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 December 1843, p 4

[2] These details are from a letter of protest from Chard to the Inspector General of Police, which was almost certainly prepared by Frederick Lee; New South Wales Legislative Council, 'Prout v Chard', Votes and Proceedings, vol 2, Sydney, 1853, p 611

[3] The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 November 1853, p 4; The Empire, 29 November 1853

[4] Michael Fitzpatrick, Clerk of the Executive Council, 4 October 1855, State Records Authority of New South Wales, AO 4/3295, file 55/10804

[5] Michael Fitzpatrick, Clerk of the Executive Council, 4 October 1855, State Records Authority of New South Wales, AO 4/3295, file 55/10804

[6] Michael Fitzpatrick, Clerk of the Executive Council, 4 October 1855, State Records Authority of New South Wales, AO 4/3295, file 55/10804