The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Aboriginal politics to 1945

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Aboriginal politics 1900–1945

We aim at the spiritual, political, industrial and social. We want to work out our own destiny. Our people have not had the courage to stand together in the past, but now we are united, and are determined to work for the preservation for all of those interests which are near and dear to us.

Fred Maynard, Sydney 1925

The city of Sydney remains the ignition point of organised Aboriginal political protest. It could be argued that the beginnings of Aboriginal political agitation are tied to the initial event of the First Fleet's arrival in 1788. However, political protest in Western terms, through organisations, petitions, rallies, conferences and the use of the media as a method of challenging government policy, was first utilised by Aboriginal people in Sydney during the early decades of the twentieth century. The two reasons for this eruption of Aboriginal political revolt are easily identified and they remain the most contentious and inflamed focuses of Aboriginal discontent – the protection of land, and of children.

The second dispossession

The later stages of the nineteenth century witnessed a far more concerted and organised approach to handling the so-called 'Aboriginal problem'. 1883 saw the establishment of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board. By 1895, 114 reserves had been granted to Aboriginal people in New South Wales. Some of these were within the Sydney region, including La Perouse, Burragorang Valley and Windsor. Of these, 72 were the direct result of Aboriginal initiative and pressure. The independent reserves were marked by Aboriginal farming success – over 80 per cent of Aboriginal people in New South Wales at this time were self-sufficient, combining European farming with traditional methods of food production. The revocation of ownership of these hard-worked-for farms, and the sudden acceleration in taking Aboriginal children from their families, were the catalysts of Aboriginal political revolt.

From 1913 to 1927, Aboriginal reserve land fell from its peak of 26,000 acres (10,522 hectares) to only half that, some 13,000 acres (5,261 hectares). Seventy-five per cent of this land loss was prime coastal land, which Aboriginal people had settled and farmed independently right up to the point when they were forcibly removed by the police. The stripping away of these lands is now recognised as the second dispossession, and resulted from encroaching settlement, white envy and the soldier resettlement schemes in the aftermath of World War I. Many of the successful Aboriginal farms were handed over to returning World War I veterans, yet, incredibly, Aboriginal returning soldiers were informed that the soldier settlement scheme did not apply to them. As Heather Goodall has indicated, it

became clear in the 1970s, that all of these revocations were in fact illegal, a problem solved by the Wran government passing legislation concurrently with its 1983 Land Rights Act which retrospectively validated this second dispossession. [1]

Growing discontent among Indigenous and oppressed groups at the conclusion of World War I was a global phenomenon. Around the world, oppressed peoples were inspired and fuelled with a surge of national and cultural pride and their political agenda was driven under the banner of 'self-determination'.

The Australian Aborigines Progressive Association

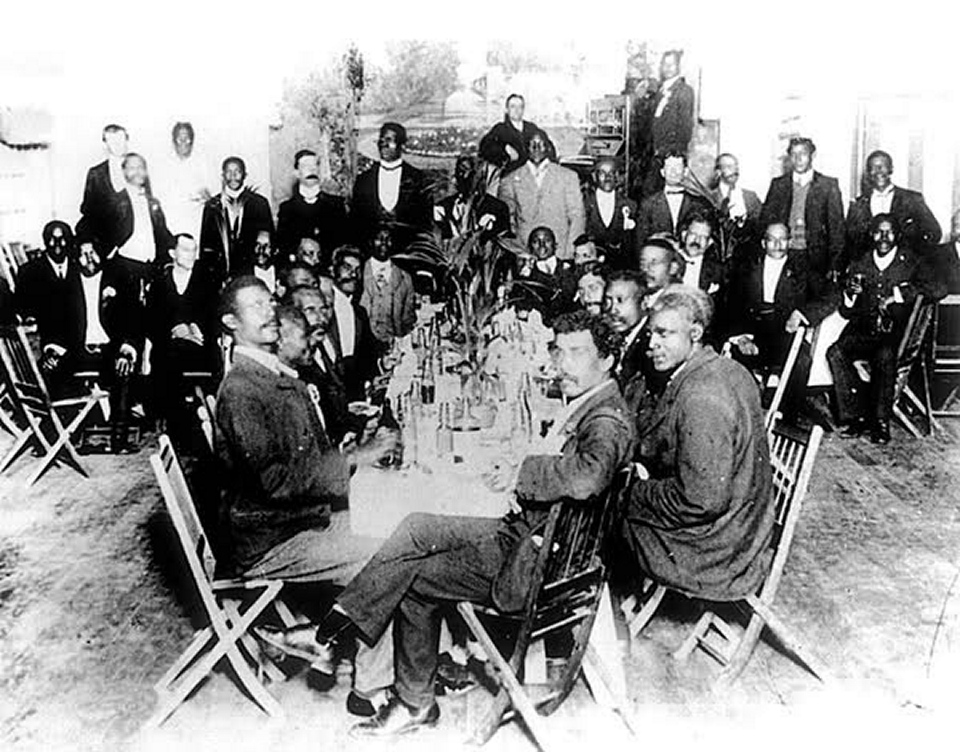

[media]The Australian Aborigines Progressive Association (AAPA), formed in Sydney in 1924, was an all-Aboriginal political organisation inspired by Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the United States. Garvey established a movement that still remains the largest black political movement in the United States' history. Garveyism was universal in its message of cultural pride and history, connection and belonging to country and self-reliance and appealed to an astonishing variety of nationalities and groups. In Australia, Aboriginal activists shaped and remodelled Garveyism to fit their own needs. They based their platform on Aboriginal rights to land, protecting their children, claiming citizenship in their own country and defending a distinct Indigenous cultural identity; it 'was an association, which suggested that they must pull together for the good of all'. [2] This organisation represented the first instance of pan-Aboriginal political mobilisation and its stand foreshadowed all that has transpired since.

The AAPA demanded that the New South Wales state government's Aborigines Protection Board be abolished and replaced by an Aboriginal Board of Management:

the control of aboriginal affairs, apart from common law rights, shall be vested in a board of management comprised of capable educated aboriginals under a chairman to be appointed by the Government. [3]

The AAPA burst into the public spotlight in April 1925 when the first of four highly successful conferences was held at St David's Hall in Surry Hills, Sydney. The conference was front-page news in the Sydney press and over 200 Aboriginal people attended, many travelling great distances from across the state. The Aboriginal political leaders were articulate, educated and eloquent men and women. President Fred Maynard was described, in the Voice of the North,

as an orator of outstanding ability, and in the not too distant future will loom large in the politics of this country, for the reason that the Aboriginal question is becoming a very important one. [4]

The AAPA was successfully registered as a company and opened offices in Crown Street, Sydney, with the phone connected. It held further successful conferences in Kempsey, Grafton and Lismore, and mounted an intensive and extensive media campaign to expose and embarrass the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board. The Kempsey conference in late 1925 ran over three days with over 700 Aborigines in attendance, discussing important issues of land, health, education and the protection of children.

In 1927, in response to the Protection Board's negative reply to an AAPA petition to the New South Wales state government, AAPA president Fred Maynard penned a powerful three-page reply:

I wish to make it perfectly clear on behalf of our people, that we accept no condition of inferiority as compared with European people. Two distinct civilisations are represented by the respective races ... That the European people by the arts of war destroyed our more ancient civilisation is freely admitted, and that by their vices and diseases our people have been decimated is also patent. But neither of these facts are evidence of superiority. Quite the contrary is the case. The members of the Board [the AAPA] have also noticed the strenuous efforts of the trade union leaders to attain the conditions which existed in our country at the time of the invasion by Europeans – the men only worked when necessary, we called no man 'master' and we had no king. [5]

After a bitter four-year campaign against the Protection Board, the AAPA eventually disappeared from public view and into temporary historical oblivion. This was a result of the combined impact of the Depression and harassment by police acting for the Board. A powerful resolution delivered by Fred Maynard at the close of the Kempsey conference in 1925 remains a fitting marker of this progressive era of Aboriginal activists:

As it is the proud boast of Australia that every person born beneath the Southern Cross is born free, irrespective of origin, race, colour, creed, religion or any other impediment. We the representatives of the original people, in conference assembled, demand that we shall be accorded the same full right and privileges of citizenship as are enjoyed by all other sections of the community. [6]

New leadership in the 1930s

Incredibly, none of the prominent Aboriginal leaders from the 1920s were visible in the new movement that emerged in the late 1930s. This was probably due to the level of police harassment and threats against the earlier Aboriginal leaders. This emerging Aboriginal leadership included such notables as William Cooper, Jack Patten, Bill Ferguson, Pearl Gibbs, and Doug Nicholls. The first significant moment for the newly formed Aborigines Progressive Association (APA) was representation on the 1937 Select Committee Inquiry on the Administration of the New South Wales Aborigines Protection Board. The secretary of the APA, Bill Ferguson, articulated the disadvantage that Aboriginal people were expected to endure:

We are asking for the abolition of the Aborigines Protection Board. You ask why should it be abolished? I say that it is not functioning in the best interest of the aboriginal people. The Board appoints managers and protectors to help the people and look after their interests. But the managers have so much power, their power is greater than any other public servant in Australia. I say that no police officer, no magistrate, or any other man, I do not believe the King of England, has power under the British law to try a man or a number of men and women, find them guilty and sentence them without giving them, fair and open trial. [7]

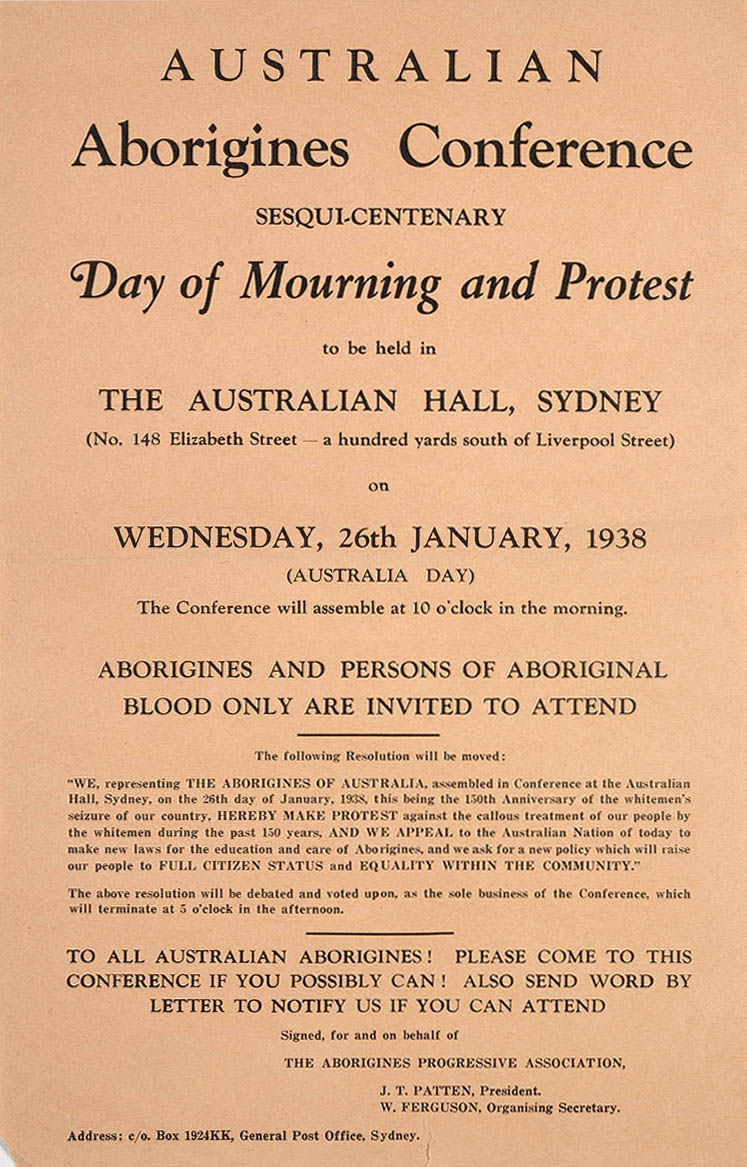

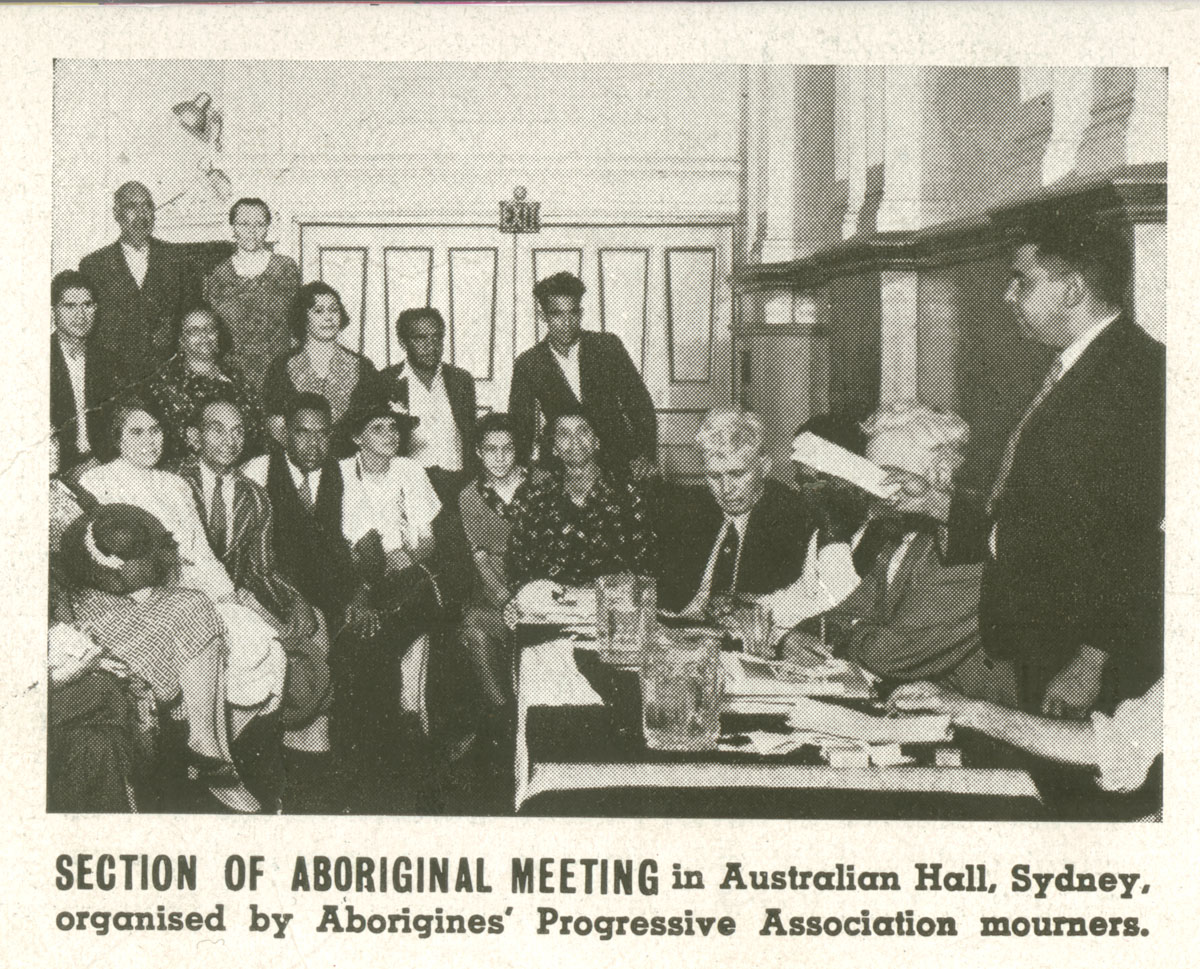

There had been one major shift from the 1920s – the new platform centred its demands on equality and citizenship. It demanded 'the same rights as other Australians and emphasised integration rather than Aboriginality in articulating its programme for change'.[8] [media]With the 150th anniversary of British settlement looming, Bill Ferguson, inspired by William Cooper and his Australian Aborigines League in Victoria, set about organising a conference to coincide and clash with the celebration of 150 years of settlement in Sydney, scheduled for 26 January 1938. It was called 'A Day of Mourning and Protest'. Before the meeting a pamphlet, 'Aborigines claim citizens rights', was distributed widely and over 100 Aboriginal people attended the conference. [media]President Jack Patten delivered the opening address:

On this day the white people are rejoicing, but we, as Aborigines, have no reason to rejoice on Australia's 150th birthday. Our purpose in meeting today is to bring home to the white people of Australia the frightful conditions in which the native Aborigines of this continent live. This land belonged to our forefathers 150 years ago, but today we are pushed further and further into the background. The Aborigines Progressive Association has been formed to put before the white people the fact that Aborigines throughout Australia are literally being starved to death. [9]

The APA published a newspaper, the Abo Call, and wrote a ten-point plan that was delivered by deputation to the Prime Minister Joseph Lyons.

The APA and the 1930s activists were to suffer a similar fate to the earlier movement but rather than the Depression and police harassment, it was the onset of World War II that stalled the momentum of their significant political protest. It would not be until the vibrant 1960s that Aboriginal agitation would achieve a similar level of sophistication and impact as witnessed during the 1920s and 1930s.

References

B Attwood and A Marcus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights – A Documentary History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1999

H Goodall, Invasion to Embassy: Land in Aboriginal politics in New South Wales, 1770–1972, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards NSW, 1996

H Goodall, 'Aboriginal Calls for Justice – Learning from History', Aboriginal Law Bulletin, vol 2, no 33, 1988

V Haskins, One Bright Spot, Palgrave, Basingstoke UK, 2005

J Horner, Bill Ferguson: fighter for Aboriginal freedom, the author, Canberra, 1994

J Maynard, Fight for Liberty and Freedom – The origins of Australian Aboriginal activism, Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, 2007

Notes

[1] H Goodall, 'Aboriginal Calls for Justice – Learning from History', Aboriginal Law Bulletin, vol 2, no 33, 1988, p 6

[2] Macleay Argus, 7 April 1925

[3] AAPA petition to Premier Jack Lang, 10 June 1927, New South Wales Premier's Department, correspondence files, A27/915; Newcastle Morning Herald, 2 July 1927; The Northern Star, 6 July 1927; The Voice of the North,10 December 1925

[4] Voice of the North, 11 January 1926

[5] Maynard, F 1927, New South Wales Premier's Department, correspondence files, A27/915

[6] Macleay Chronicle, 7 October 1925

[7] B Attwood and A Marcus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights – A Documentary History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1999, p 75

[8] B Attwood and A Marcus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights – A Documentary History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1999, p 59

[9] B Attwood and A Marcus, The Struggle for Aboriginal Rights – A Documentary History, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1999, p 87

.