The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Free Public Library

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Free Public Library

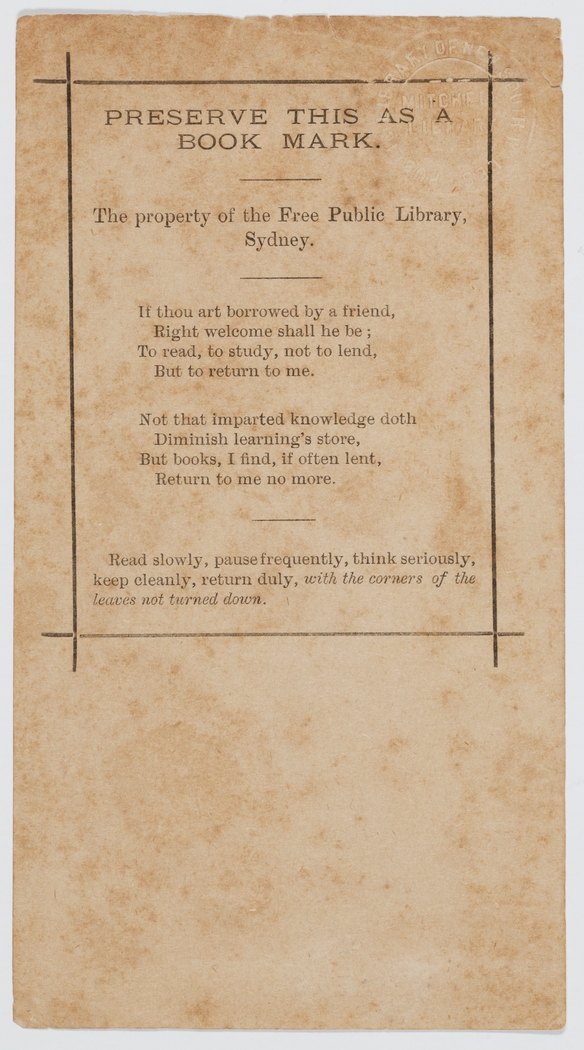

[media]The opening of the Free Public Library — which we now know as the State Library of New South Wales — on 30 September 1869 by the New South Wales Governor, Earl Belmore, was a gala affair. Above a bust of William Shakespeare, a large portrait of Captain Cook dominated the official dais. Other windows were decorated with portraits of Sir Joseph Banks, Christopher Wren, Plato and Phidias: exemplars of the Library’s aspirations.

[media]The Free Public Library arose from the ashes of the Australian Library and Literary Institution and its immediate predecessor, the Australian Subscription Library.

The Australian Subscription Library

[media]The Australian Subscription Library, which opened in 1826, had initially operated as an exclusive organisation for gentlemen readers. But its continued failure to deliver a viable library forced it to be more inclusive. By the 1860s, the Australian Library, as it now called itself, had also proved unsustainable, and it turned to the New South Wales government as a potential saviour.

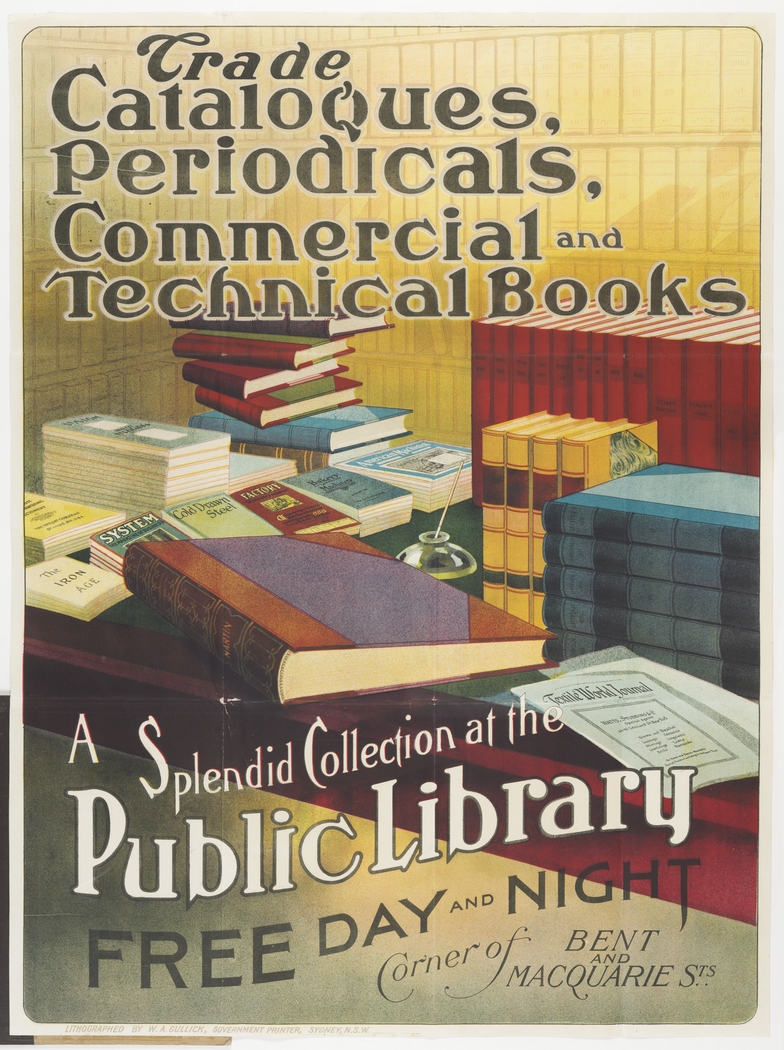

In September 1869 the government purchased the book stock of the Australian Library for £1500 and the building for £3600. Although the building, on the corner of Bent and Macquarie streets (diagonally opposite the current Library complex), was in poor condition, the Library remained on this site until 1942 when the magnificent Mitchell Library Reading Room, then called the Public Library Reading Room, opened to the public.

The imperative to ‘convey knowledge and truth to the ignorant’

[media]For much of the 1850s and 1860s the idea of a free public library had rolled around the Sydney press. Melbourne’s Public Library (now the State Library of Victoria), which opened in 1854, was an obvious model, but public libraries were still a comparative novelty across the colonies, and even in England itself. There were other subscription-based libraries in Sydney — the Mechanics School of Arts, for instance, was proud of the some 8000 books on its shelves by 1860, although critics despaired of the demoralising influence of its substantial popular fiction holdings.

For the colonists who engaged in public debate about libraries, a quality library collection meant useful educational books that improved the capacity and self-reliance of the working classes. For some, like ‘GHR’, who wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald on 8 August 1865, the imperative of public libraries was to ‘convey knowledge and truth to the ignorant’.[1] For this reader, concerned that suffrage was rapidly devolving to the lower classes, libraries offered a free education to potential voters.

More optimistically, the Illustrated Sydney News declared in 1875 that libraries delivered ‘that diffusion of knowledge, which is so essentially a characteristic of a country’s social and moral progress’.[2] Earl Belmore himself noted that the Free Public Library was the only place where the ‘adult labouring classes’, having missed out on the education now provided to the colony’s children, could improve themselves.[3]

Popular fiction, on the other hand, was dangerously and frivolously enervating. Classic literature and drama, like Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley novels, was acceptable, but the Trustees who assumed control of the Library in September 1869 immediately withdrew some 2100 mostly popular fiction books from the 16,000 or so they had just purchased: as a consequence the numbers of readers using the Library dropped by 12%.

'Everything treating of Australia'

[media]Although the Free Public Library opened with only three staff and limited resources, its fortunes rapidly improved. Contemporary European periodicals brought new readers to the Library. Donations like Justice Wise’s bequest of early Australian publications inspired a focus on collecting colonial records: by 1889 the Australian Town and Country Journal noted

that the Library pursued with ‘great perseverance … everything treating of Australia … pamphlets, journals, magazines and paper.[4]

It was the intelligence and perspicuity of this collecting which attracted into the Library’s orbit its two great Australiana benefactors, David Scott Mitchell and Sir William Dixson.

Lending branch

[media]A lending branch of the Library opened in 1877 (now known as the City of Sydney Library, it was transferred to the control of the Sydney Municipal Council in 1909). A country lending service was established in 1883 to service regional New South Wales.

The Public Library of New South Wales

[media]In 1895 the Free Public Library was renamed the Public Library of New South Wales, to reflect the ‘scope of its operations and its national character.’ A nascent profession of librarianship began to emerge, and Principal Librarians like Henry Anderson and William Ifould elevated the Library’s role in Sydney’s cultural life through their intelligent and passionate advocacy for its services and resources.

The opening of the Mitchell Library in 1910 significantly added to the prestige and international importance of the Library, and contributed to an understanding of the relevance of libraries to contemporary Australian life. Indeed, this was the foundation upon which the Free Library Movement of the 1930s was built. Without the inspiration of the Public Library of New South Wales it is difficult to see how the Library Act 1939 — which led to the growth of the public library network throughout New South Wales — could have been so successfully realised.

Notes

This article was first published in the Spring 2019 edition of SL Magazine.

[1] A Free Library for the People, Sydney Morning Herald, 8 August 1865, p5 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13117149

[2] Primary Education, Illustrated Sydney News, 26 June 1875, p2 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63106641

[3] The Public Library, Sydney, Illustrated Sydny News, 27 October 1869, p279 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63514741

[4] Australian Town and Country Journal, 28 September 1889, p31 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article71123980