The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

French

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The French

The French presence in Sydney has always been radically different from that of other ethnic groups. The rich and complex legacy of French–British relations over the best part of a thousand years includes centuries of conflict and of alliance between continental France and what was to become Great Britain. [media]French language and culture have also had a privileged place in the formation of the language and culture of the British Isles. This goes some way towards explaining the unique influence of French people and French culture on the Australian continent in general and on Sydney in particular.

French influence in Sydney has always been qualitative rather than quantitative. The French-speaking community has been comparatively small and its members have tended to see themselves as expatriates rather than migrants. They often end up staying for good, but rarely do they come with that intention. French influence can be measured by the number of French companies installed in the local market, the monetary value of their investments, the number of French cultural manifestations in Sydney (films, television programs, plays, concerts, and exhibitions), the space devoted by the local media to items with a French theme, the number of Australians studying French, or the number of Australians visiting or living in France. However it is measured, there is a striking disproportion between the statistical strength of the Sydney French community and French influence on Sydney.

The early days

Until the middle of the nineteenth century the total number of French residents in Australia has been estimated at no more than 400, of whom perhaps 75 per cent were Sydney-based.

Other than the early explorers, the first French arrived here as convicts sentenced to transportation by British courts. They were soon followed by aristocratic émigrés from revolutionary France, generally also via England, their first place of refuge. These early French residents, whether convicts, political refugees or free settlers, tended to be people with initiative and ideas. If they were not already educated and trained, they quickly acquired skills which allowed them to contribute to this country's commerce, industry, public service or cultural activities. Their entrepreneurial flair led them to take risks, and their careers often followed a pattern of ups and downs.

James Larra, variously described as a French or Spanish Jew born in France, arrived from England as a convict in 1790. He became an innkeeper and a merchant, owner of the Freemasons Arms in Parramatta, Sergeant-Major in the Loyal Parramatta Association, and a well respected citizen. The dubious circumstances of his second wife's death ruined his reputation and the profligacy of his third wife, a young English actress, ruined him.

Monsieur Morand, a clockmaker and goldsmith by trade, had been convicted, together with his Irish associate, of trying to sabotage the Bank of England by manufacturing counterfeit notes: their motivation was political rather than financial. Morand eventually became a prosperous citizen in Australia.

Huon de Kerilliau, an aristocratic refugee from the French Revolution, arrived in Port Jackson in 1794 via England, as a private in the 102nd Regiment under John Macarthur. Subsequently employed by Macarthur as a French tutor to his children, he became one of the pioneers of the pastoral industry in the Campbelltown district.

Lalouette de Vernicourt, also known as Chevalier de Clambe, was another early character, who settled on 100 acres (25 hectares) at Castle Hill in 1802 after a colourful military career.

Prosper de Mestre was a free settler of French origin who came to Sydney in 1818 from America via China, Mauritius and India. Rumour has it that he was the illegitimate son of the Duke of Kent, father of the future Queen Victoria. He became a successful business leader in Sydney. One of the early directors of the Bank of New South Wales, he was also a founder of the local insurance industry, and became involved in shipping and whaling. A member of the committee of the Agricultural Society of New South Wales, he retired to Terara, on the Shoalhaven River, where his son bred five Melbourne cup winners, including the winner of the first two.

Francis Rossi, born in Corsica, was Superintendent of Police in New South Wales, a post he took up in 1825. His tenure lasted ten years, with two periods of what we would now call stress leave. His efforts to reform and centralise the New South Wales police encountered countless obstacles, such as lack of funds, insubordination, inadequate support from the governors, allegations about his past career and accusations of corruption (all disproved), and last but not least criticisms of his foreign background and accent. Rossi and his family retired to the Goulburn district.

The mid-nineteenth century

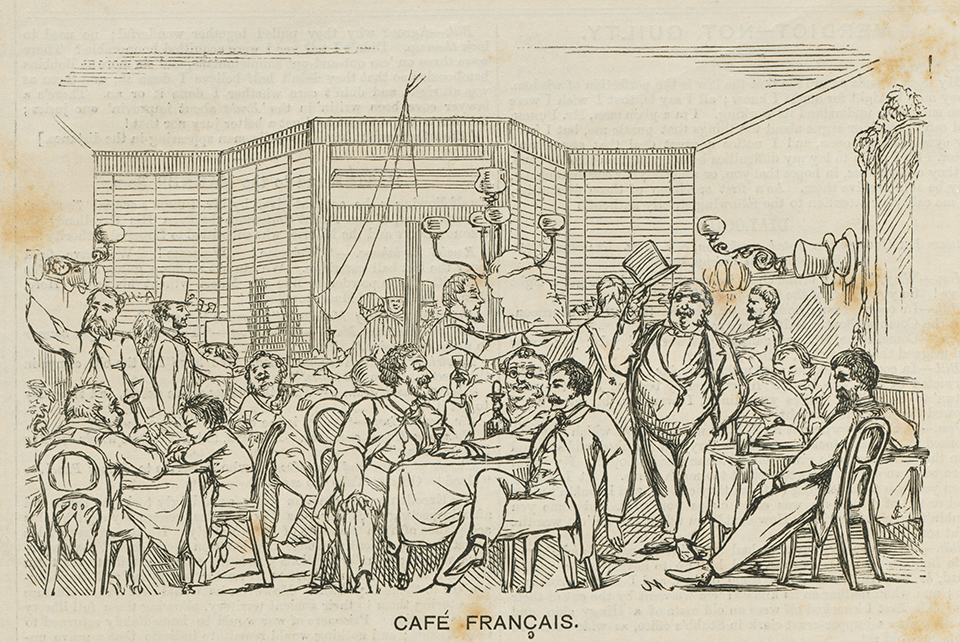

Some French [media]merchants in the region were quick to perceive the commercial potential of Sydney. As early as 1826 one of the most dynamic French merchants in the Pacific, Antoine Hervel, suggested to his government that it set up a Consulate General in Sydney, which he saw as the future capital of the Pacific, with vice-consulates in California, Hawaii and one of the Pacific islands. While this ambitious plan failed to eventuate, 13 years later on 8 August 1839 Louis Philippe, King of the French, signed a decree creating a French [media]consulate in Sydney, the first foreign consulate in Australia. Its first incumbent, Jean Antoine Marie Faramond, took up his post in May 1842.

From 1850 onwards, the gold rush and the progress of general commerce with France, especially the growth in wool sales, gradually attracted more French residents. Some of the recently arrived French migrants, originally attracted by the discovery of gold, stayed on and proved to be multiskilled settlers, making a success of their new life on this continent as farmers, vignerons, shopkeepers, engineers, manufacturers and artisans. There were also doctors, teachers, musicians and artists among them, making a contribution to the Sydney community at large as well as to the intellectual and artistic life of the colony, as did the many visiting French personalities (musicians, singers, actors, painters, writers and more) whose number grew exponentially during the remaining decades of the century.

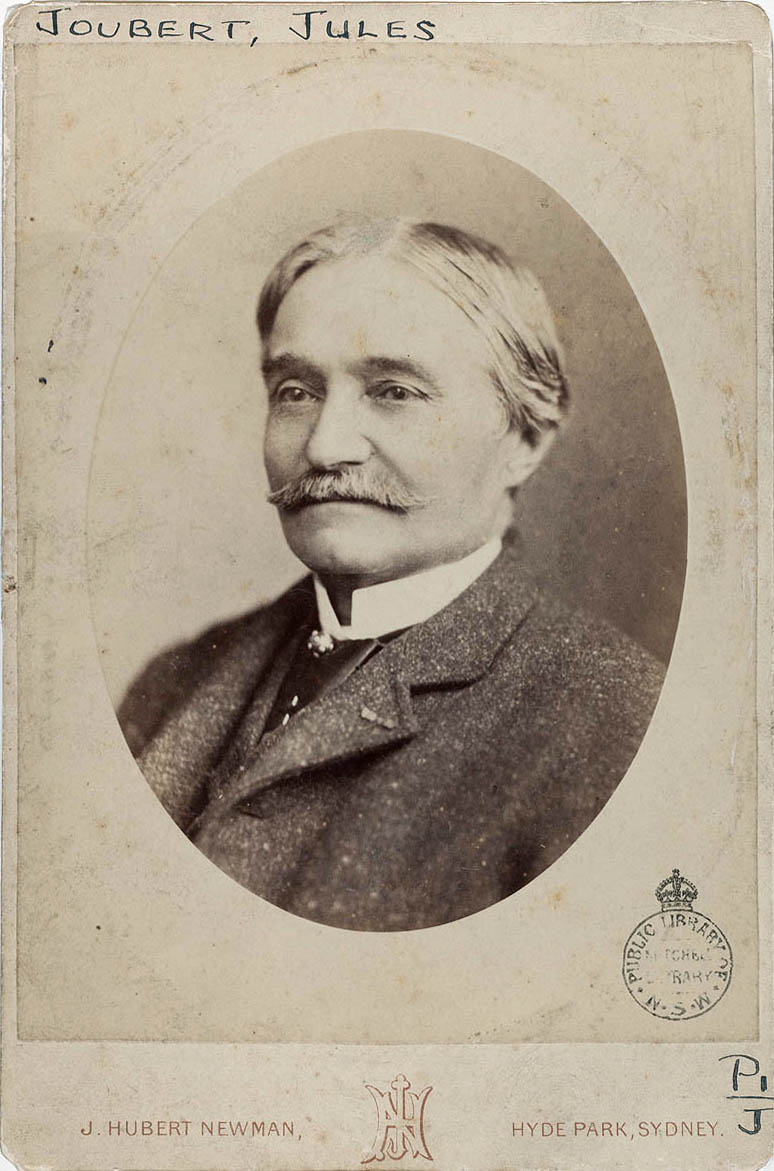

A striking example of mid-nineteenth century French entrepreneurial spirit was the contribution of the Joubert brothers, founders of Hunters Hill in Sydney, often referred to at the time as 'the French village'. One of them, the restless and adventurous Jules Joubert, was also associated with the international exhibition movement, and was one of the architects of the New South Wales Agricultural Society Show, the future Sydney Easter Show.[media] The first daguerreotype arrived in Australia in April 1841, thanks to Augustin Lucas, the captain of the French ship L 'Oriental, and the first documented photograph in Australia was taken on 13 May 1841 in the Sydney store of Messrs Joubert and Murphy.

In the following decades Sydney, or more precisely Hunters Hill, also became the Pacific headquarters of the influential French teaching order, the Marist Brothers.

The late nineteenth century

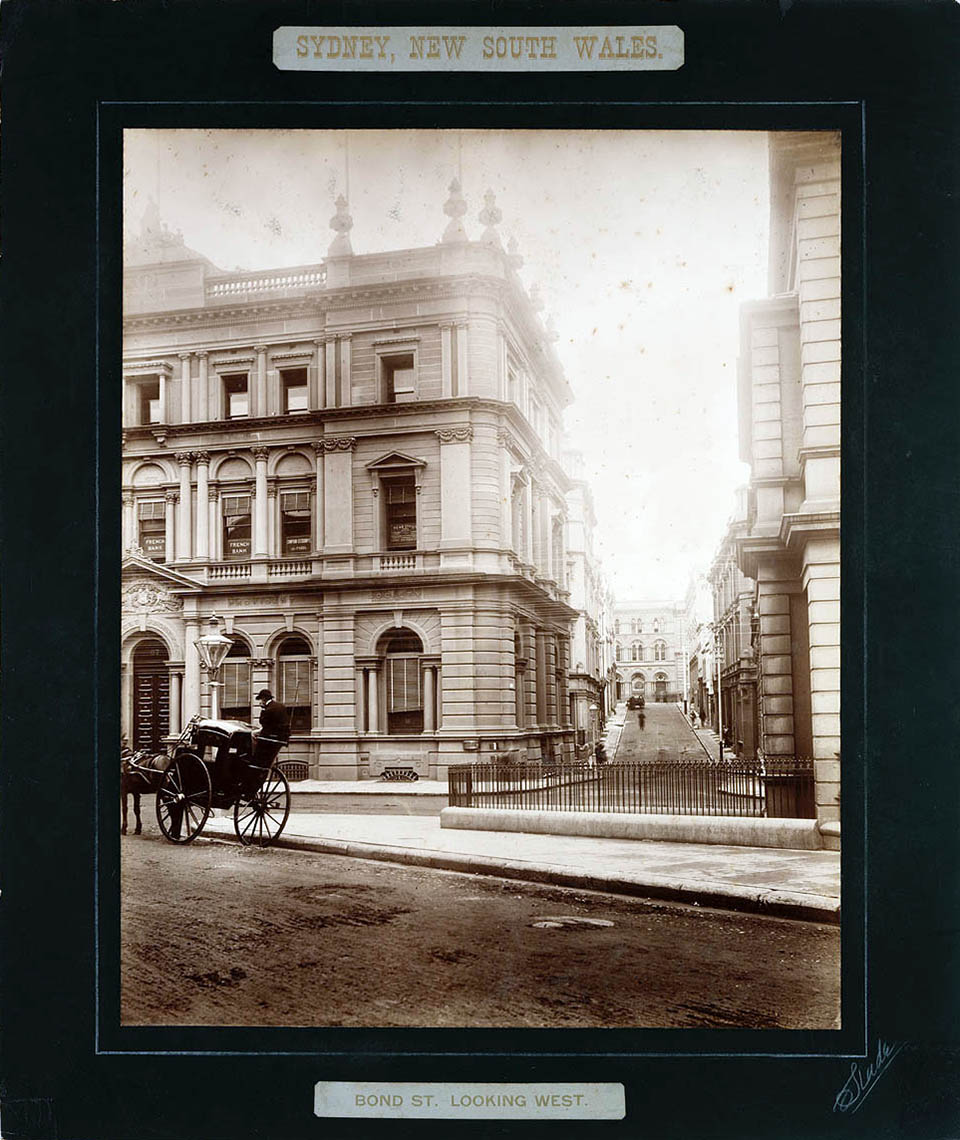

By the second half of the nineteenth century the highly successful French textile and leather industries developed into avid consumers of Australian wool and skins and began to establish local offices in Sydney. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 and the telegraphic link between Australia and Europe in 1872 accelerated the expansion of commercial relations. [media]In 1881 a French bank (the Comptoir National d'Escompte de Paris, predecessor of BNP Paribas), opened on the southern corner of Bond and Pitt Streets, and it was followed a year later by the shipping line Messageries Maritimes (later Compagnie Générale Maritime).

Some of the woolbuyers settled here permanently, founding prosperous French-Australian families. By the 1890s, the woolbuyers constituted the active core of the local French colony, and their prestige and influence continued to dominate the life of the French community until World War II and beyond. [media]The Playousts, the Lamérands and the Paroissiens were amongst the first, followed by the Dekyvères, the Flipos, the Decouvelaeres, the Droulers and many others. Their offspring occasionally intermarried and sometimes they married out. These families became thoroughly bilingual and their loyalties were shared rather than divided between France and Australia. For all practical purposes they had dual nationality at a time when such an institution was yet to be formalised.

The woolbuyers were also instrumental in setting up the Sydney French colony's infrastructure, together with Sydney's first French Consul-General, the influential Georges Biard d'Aunet, whose tenure lasted 12 years (1893–1905) and whose second wife was Lady Innes, the widow of Sir George Innes, a former Attorney General and Supreme Court judge. The French Benevolent Society (1891), the French newspaper Le Courrier Australien (1892), the French Chamber of Commerce and the Alliance Française (both in 1899) were all established within the decade. All their offices, as well as the Consulate General, were housed at 2 Bond Street, on the corner of George Street. These institutions have now been in continuous existence for over a century.

More than half a century after the arrival of the daguerreotype in Sydney, the French were responsible for another Australian first. Sydney photographer Walter Barnett brought out Marius Sestier, a French cameraman from the Lumière Studios, and on 22 September 1896 Sestier shot the first Australian film on Sydney Harbour. Barnett and Sestier subsequently went to Melbourne to film the 1896 Melbourne Cup.

[media]During this period of expansion the number of French residents in Australia rose to the record figure of 4,200 (1890 census), which implies a Sydney total of at least 1,500.

After Federation

When, contrary to European expectations, post-Federation Australia repudiated its late nineteenth century cosmopolitanism and closed in upon itself, implementing the White Australia policy and imperial preference, the French presence in Sydney also declined.

Despite the intensely pro-French feelings which prevailed in Sydney during World War I, the French presence recovered only temporarily when some diggers returned with French brides after 1918. The numerical decline continued in the 1920s and the 1930s, and lasted until well after World War II when at last Australia reopened its borders to new settlers.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century the French and French-speaking Belgian woolbuying families continued to play a prominent role in Sydney society, bringing to local fashions, dining, charity balls, and other social activities, a flair which was all the more appreciated as it was both genuinely French and appropriately adapted to local tastes: they were frequently featured in the social pages of the Sydney press. The woolbuyers also continued to run the committees of the local French community, providing both material support and leadership. Sharing the control of the Alliance Française with some Sydney academics, they actively participated in the production of French plays and the organisation of other cultural activities.

After France's defeat at the beginning of World War II, the French were divided between supporters of the Vichy government prepared to cooperate with Nazi Germany, and the Free French movement launched from London by General de Gaulle, determined to resist the occupier and support the Allies. The Sydney French community promptly declared itself for General de Gaulle and throughout the war years Sydney was a rallying point for the Free French forces in the Pacific.

The postwar period

In 1947 the French-born population in Australia fell to a low of 2,200. From that point onwards the number of the French began to grow again, to reach 19,180 in 2006, of whom over 7,000 were in New South Wales. These are the official Australian census figures, covering Australian residents born in France.

According to the French Consulate General, at the beginning of the twenty-first century the total French community for the whole of Australia was closer to 50,000, a figure which also included the children of residents born in France, as well as persons born in the French colonies and overseas territories, and their children. Sydney's share of that figure would be approximately 17,000. Sydney also hosts a rapidly growing number of French tourists and other French visitors: the annual national figure for these is now around 100,000, a third of whom come from New Caledonia.

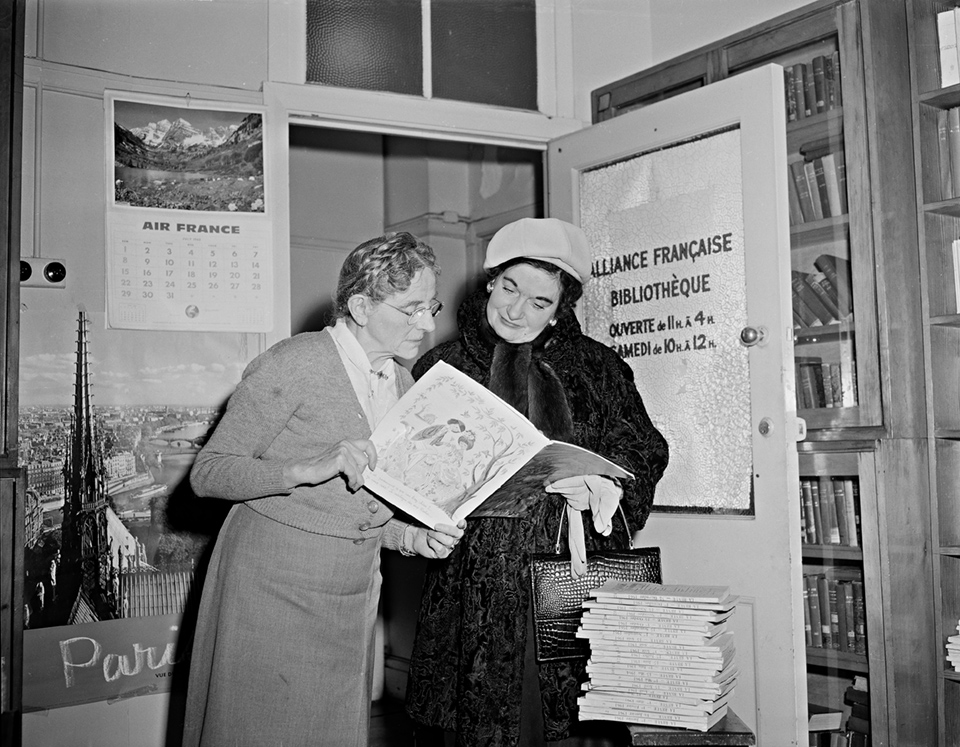

[media]In the 1950s and 1960s the growth was partly due to Australia's encouragement of European migration through a system of assisted passage, and partly to the disintegration of the French colonial empire and the desire of some French colonists to migrate to a new country with a warm climate.

Another determining factor was the successful overseas expansion of new French industries (the construction industry, the aircraft and car industries, defence, pharmaceutical products among others) which has continued throughout the second half of the twentieth century and well into the opening years of the twenty-first. In 1900 the value of French imports to Australia (mainly food, wines and luxury products) was only approximately 10 per cent of the value of Australian exports to France. This imbalance was gradually reversed after World War II and the balance is now very much in favour of France. French investment in Australia is more significant than French imports: approximately 270 French companies operate in the Australian market, frequently using their Australian headquarters, predominantly located in Sydney, as their bases for the Asia-Pacific region.

This industrial and financial presence accounts for the number of temporary French expatriates and their families living in Sydney. The presence of these top executives is highly visible, but it should not obscure the contribution of the large number of 'ordinary' Australians of French birth who live in this city: the 2006 naturalisation statistics suggest that 82.5 per cent of French-born residents choose to become Australian citizens, compared with an overall rate for the overseas-born of 75.6 per cent. French-born Australians tend to be better educated and command higher incomes than the overall Australian population.

Australian–French antagonism

On several occasions in its history the Sydney French colony has felt the disapproval, ranging from mild to violent, of the general Australian community as a result of actions of French governments. The French takeover of Tahiti in 1843 and the occupation of New Caledonia in 1853 are examples of such actions. In the final decades of the nineteenth century the control of the New Hebrides, now Vanuatu, was another cause for tensions between Australians and the French. The most dramatic clashes, however, occurred in the last three decades of the twentieth century. They were due to the French government's nuclear tests in the Pacific, often described as 'Australia's backyard'. Possibly the worst took place in 1995, when the newly elected president, Jacques Chirac, decided to resume the testing program, which had been suspended by his predecessor, François Mitterrand. The program was permanently terminated, arguably as a result of a combination of international and domestic pressure, in January 1996. Although most French residents of Sydney were against the tests, many of them were nonetheless personally attacked and victimised by members of the general community and the media. It is a common pattern in French-Australian relations that conflicts are promptly forgotten and friendship restored, at least until the following incident. The same sudden reconciliation occurred early in 1996.

An open community

What distinguishes the French from many other ethnic groups in Sydney is their reluctance to form closed groups. Far from using their language and culture as a means of strengthening their community's cohesion, they are anxious to share their language and culture with others. Two examples of this openness to the general community are the Sydney French school and the Sydney Alliance Française.

To serve the needs of the French community, a French school was established in Bondi as early as 1969. This institution has since grown into the Lycée Condorcet, permanently established on the site of the former Maroubra High School. Although supported by the French government, the Lycée Condorcet is not an exclusively French school: it is bilingual and it welcomes Australian students.

As we have seen, the Sydney Alliance Française was established over a century ago, primarily for the benefit of Australians wishing to familiarise themselves with the French language and French culture, but it has also been a gathering point for the local French community. Although since the 1960s its classes and activities have been run professionally by specialists appointed by the French government, the Alliance Française has remained a cultural and social club managed by an elected French-Australian committee where Australians can meet French people and interact with them – another example of openness and cross-cultural cooperation.

References

Robert Aldrich, The French Presence in the Pacific, 1842–1940, Macmillan, London, 1990

Robert Aldrich, France and the South Pacific since 1940, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1993

Australian Government, Statistical information (2006 census) http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/comm-summ/_pdf/france.pdf

Margaret Barrett, 'Australians and French nuclear testing in the Pacific, 1995–96', BA honours thesis, Department of Modern History, Macquarie University, 2007

Eric Bouvet, 'French migration to Australia in the post WWII period: Benevolent tolerance and cautious collaboration', Fulgor (Flinders University Languages Group Online Review), vol 3 no 2, 2007, pp 15–37, http://ehlt.flinders.edu.au/deptlang/fulgor/

Jacqueline Dwyer, Flanders in Australia – A Personal History of Wool and War, Kangaroo Press, Sydney, 1998

Anne-Marie Nisbet and Maurice Blackman (eds), The French-Australian Cultural Connection, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 1984

John Rosemberg, 'A Steady Ethnic Group: Role of the French in Australia', Ethnic Studies, vol 2 no 3, 1978, pp 52–57

Anny PL Stuer, The French in Australia, Immigration Monograph Series 2, Department of Demography, Australian National University, Canberra, 1982