The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Parkes, Henry

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Parkes, Henry

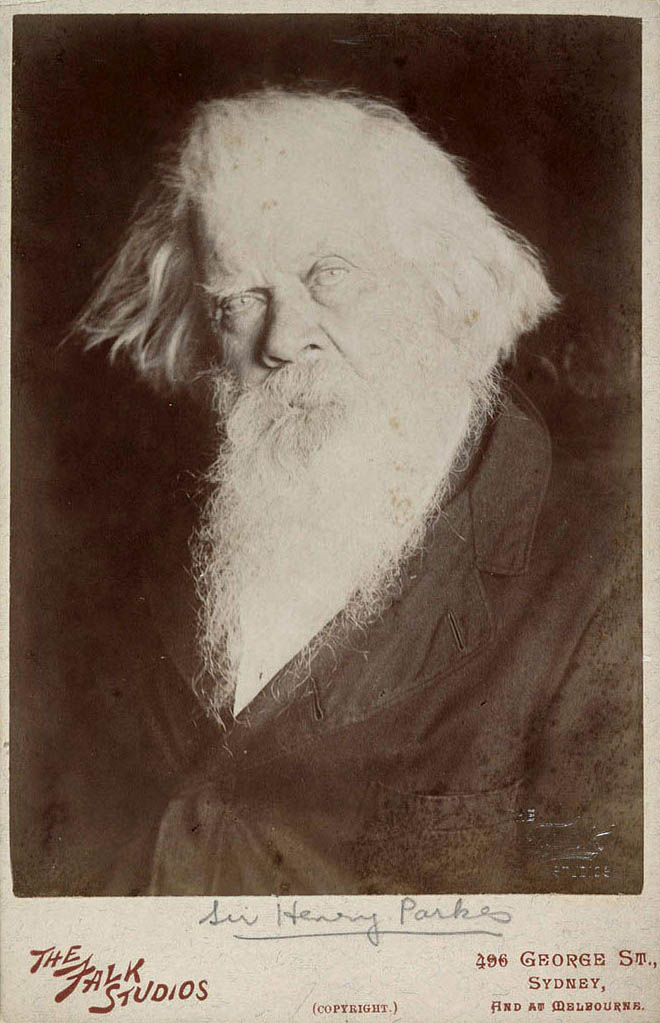

Henry Parkes [media]cast a long and wide shadow over politics in Sydney in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Born in 1815, he was the son of a yeoman farmer who was forced off his rural holding into the city of Birmingham in England's newly industrialised midlands when Henry was 10. Young Parkes was educated for only a few years and later attended a mechanics' institute. His lack of formal education made his political, literary and oratorical skills all the more remarkable.

In his teens, Parkes served an apprenticeship as an ivory turner and set up his own business when he was 22. His business in Birmingham did not prosper, nor did he find London any better when he sought his fortune there. Before leaving Birmingham however, he had observed the political agitation that led to the passing of the first Reform Act of 1832. Parkes was greatly impressed and influenced by the quality of the oratory at these populist meetings, and even joined the Political Union, the alliance that advocated the bill. [1]

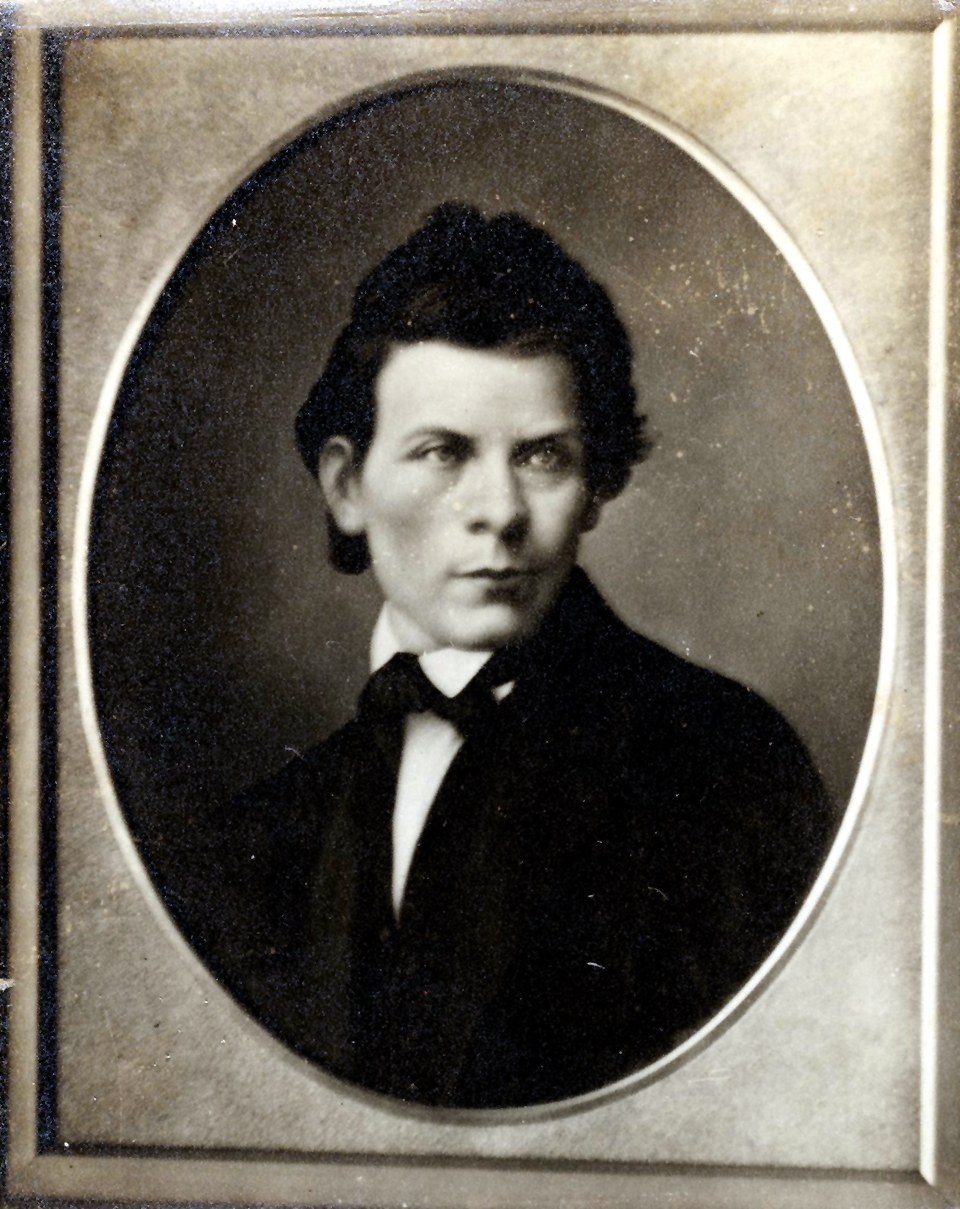

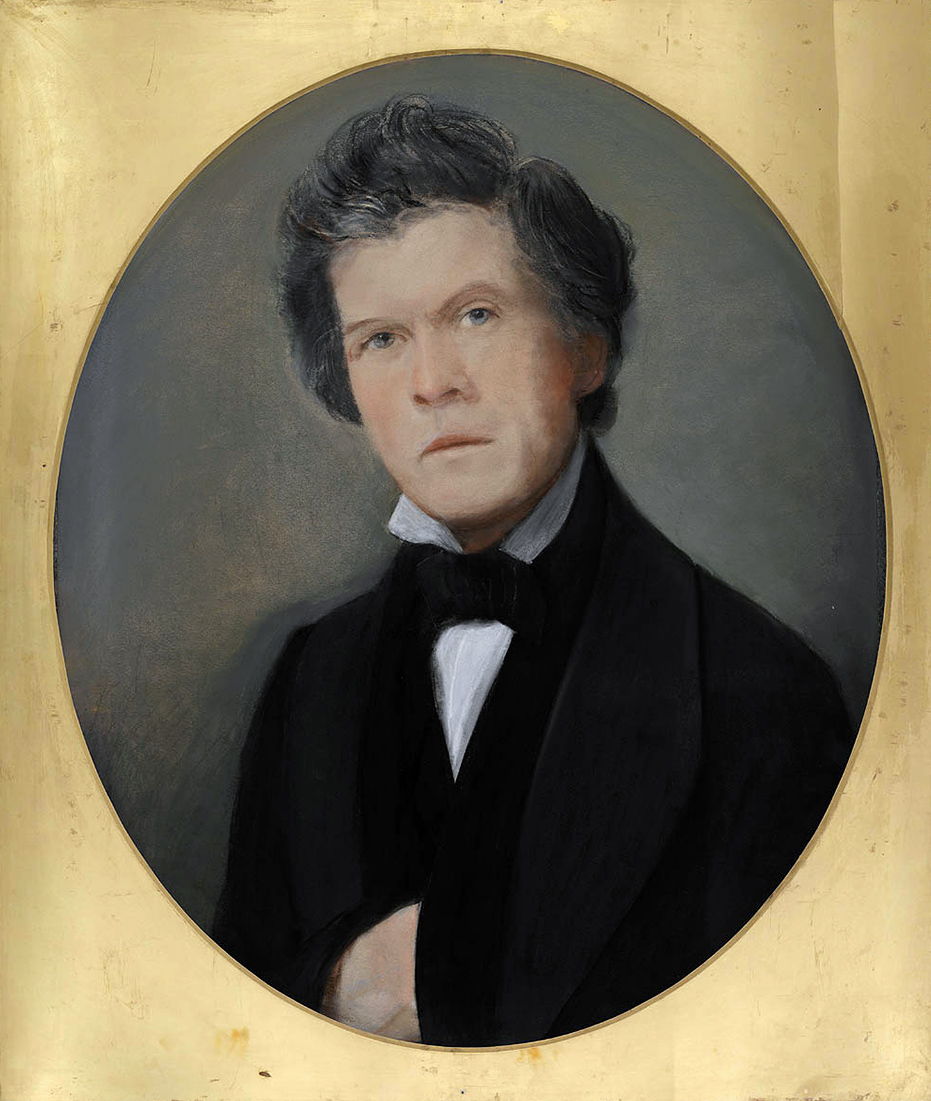

Arrival in Sydney

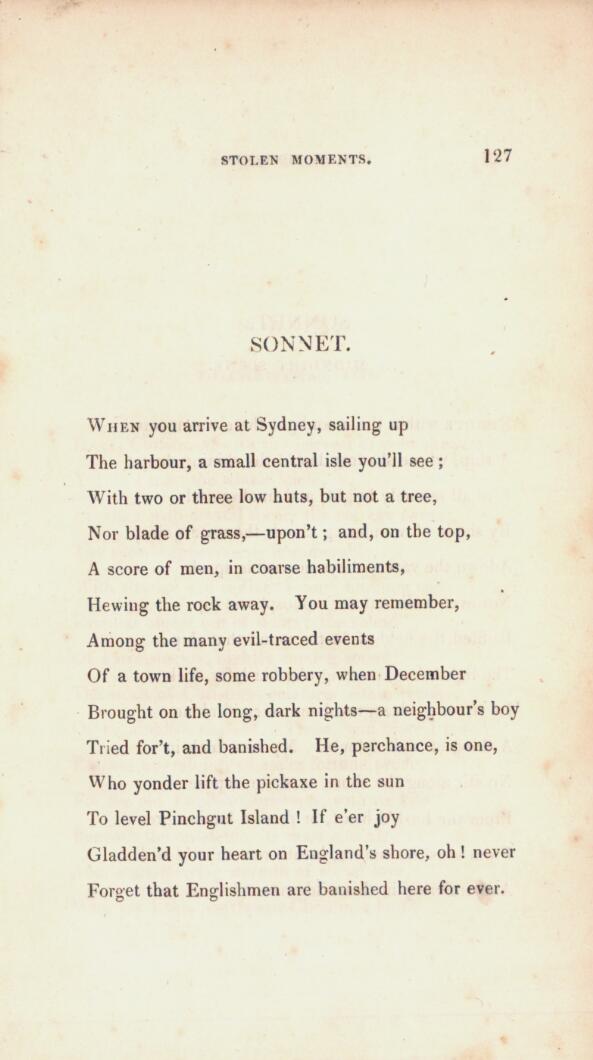

Parkes, his [media]first wife Clarinda and their newborn child reached Sydney in 1839 on an immigrant ship at a time when there were 1,200 other immigrants on ships in the harbour waiting to land. Parkes and his wife did not know a soul in the colony, nor did they hold any letters of introduction. He must have felt as lost and as far from home as many of the others waiting on the [media]water.

I was one of that floating crowd of adventurers … Of necessity we had to remain on board some days. In those wearisome days of vague hope, fitful despondency, and youthful impatience, many hours of the early morning I spent hanging over the ship's side, looking out upon the monotonous, sullen and almost unbroken woods which then thickly clothed the north shore of the harbour. [2]

[media]Parkes arrived in the colony too late to take advantage of the economic growth of the 1830s. The only work he could find was as an agricultural labourer on Sir John Jamison's estate, Regentville, near Richmond, 58 kilometres west of Sydney. He later worked at Thomas Burdekin's foundry and in a brass works. It was not until 1845 that he had saved enough money to set up an ivory-turning and import business in Hunter Street. He and his family lived above the shop.

Liberal or radical?

From the late 1840s Parkes began to speak in public on behalf of the free immigrant middle and working classes. He was [media]in favour of an extension of the limited franchise granted in 1842, and against the resumption of transportation to the Australian colonies. His views offered a more or less middle course between liberalism and radicalism through much of the nineteenth century.

However, throughout his long political career, he could never be accused of rigid consistency. One of the vehicles for the combination of the radicals and liberals against the conservatives was Parkes's newspaper, The Empire, published between 1850 and 1858. Parkes strongly opposed WC Wentworth's outmoded views on constitutional reform.

Election to parliament

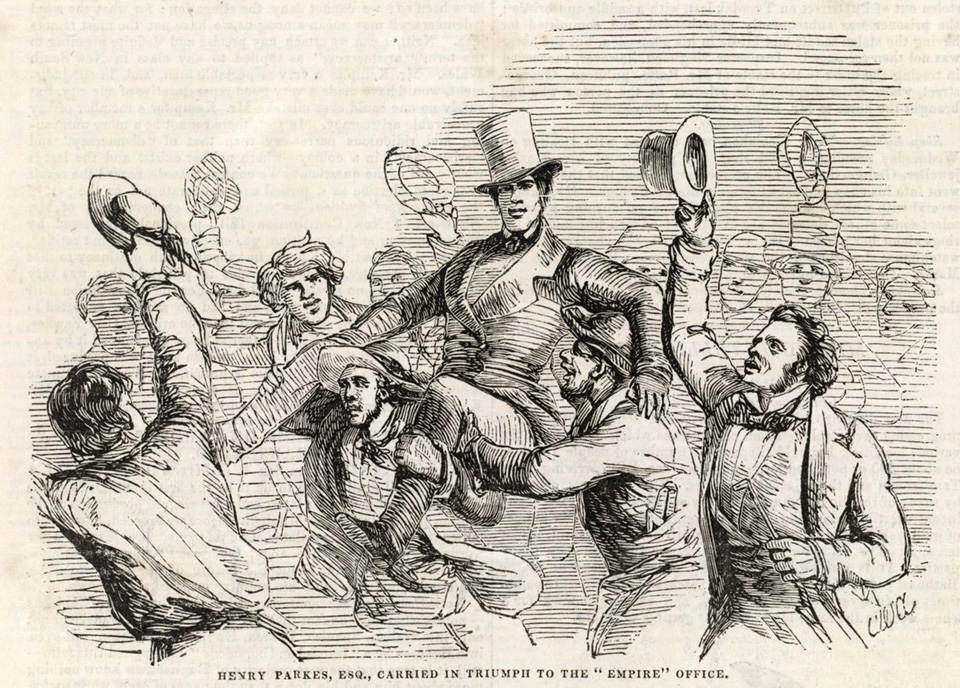

In 1854, Parkes [media]won the seat of Sydney when Wentworth retired from politics and left for England. He won the election by a convincing two-to-one majority over his opponent Charles Kemp, one-time part-owner of the Sydney Morning Herald. His constituents were people like him – recently arrived free immigrants from working- or middle-class backgrounds – who did not care to be politically represented by conservatives. Parkes's political career was intermittent because of persistent financial problems and the vicissitudes of the electoral process, but spanned 40 years.

One of Parkes's early public responsibilities was to chair a parliamentary select committee established in 1860 to enquire into the condition of the working classes. Housing conditions were deplorable for many Sydneysiders. People lived in hovels, high rents led to overcrowding and there were 1,000 vagrant children roaming the streets. Many young girls were forced into prostitution. Parkes's contribution to that inquiry brought him to public attention and he was elevated to James Martin's ministry as colonial secretary in 1866.

Parkes, affected [media]by what he had learned of the condition of young children while serving on the select committee, created a nautical school for male orphans on a hulk in Sydney harbour, the Vernon. He also introduced professional nursing to New South Wales when he brought out Lucy Osburn, a nursing sister trained by Florence Nightingale, to teach local women. Education was another priority. He created a council to oversee denominational and religious schools.

Premier Parkes

After a period in the political wilderness brought on by financial difficulties, Parkes became premier (then called prime minister) in 1872. He put into place his free trade policies and embarked on an ambitious public works program. His first premiership came to an end in 1875 in a parliamentary battle over the right of the governor to remit the notorious bushranger Frank Gardiner's long jail sentence. Public opinion was against clemency. The governor and Parkes thought that Gardiner's exemplary conduct in the 10 years between his escape from custody and his recapture in Queensland demonstrated a capacity to abide by the law. The general population, fired up by a law-and-order campaign stoked by Parkes's political rivals, were furious that Parkes and the governor would not yield to public pressure. Parkes lost control of the Legislative Assembly and was thrown out of power until 1878.

A second term

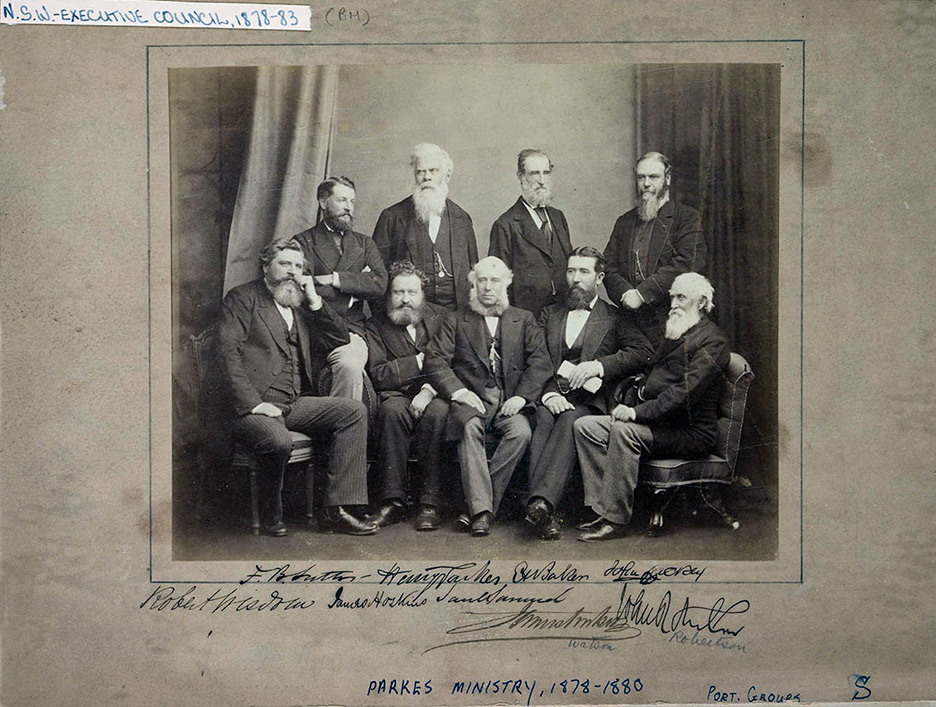

In his second term [media]as premier, Parkes's main achievement was to reform the education system. Government-funded education became free, compulsory and secular, though truancy rates remained high. State aid was withdrawn from religious schools. The abolition of state aid was an issue that festered among Catholics for another 83 years. Catholics saw themselves as the main victims of the change and believed they were being singled out for harsh treatment.

A less controversial step was to provide greater access to learning for the working classes. Free libraries had been established in the 1860s, when there were already 30 bookshops in Sydney. [3] In 1878 a working men's college was founded and, by 1892, there were 2,000 enrolments. [4] This institution evolved into the Sydney Technical College and later formed the nucleus of the University of New South Wales, Sydney's second-oldest university, established in 1949.

Parkes's government lost office again in 1883. By that time he was referred to in the London Times as 'the most commanding figure in Australian politics'. [5] He led another government from 1887 [media]until 1891, having campaigned on a platform of free trade and honest government, and was in charge of the police and military during the maritime strike of 1890.

Federation and Parkes's legacy

From the late 1880s, Parkes's attention moved from parliamentary matters to the issue of the joining of the colonies to form a nation, later known as Federation. He was the driving force for Federation in New South Wales, which was the largest colony at the time of the final referendums but the least convinced of Federation's benefits.

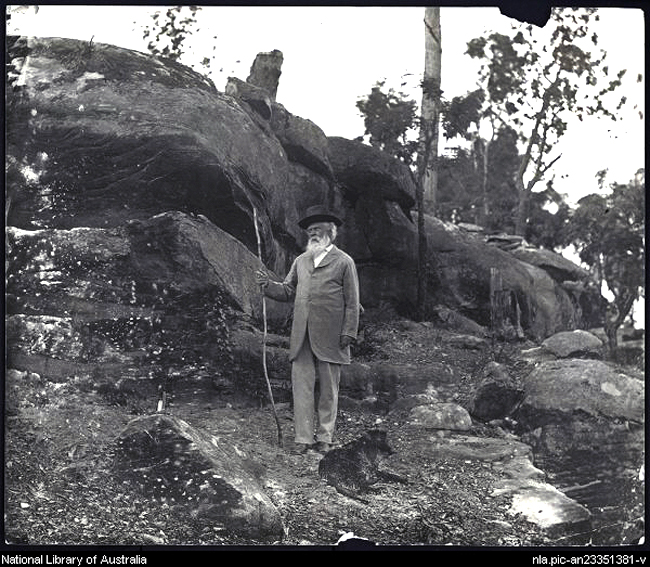

After [media]Parkes's death in 1896, at Kenilworth in Johnston Street, Annandale, Alfred Deakin said of him:

Though not rich or versatile, his personality was massive, durable and imposing, resting on elementary qualities of human nature elevated by a strong mind. He was cast in the mould of a great man and though he suffered from numerous pettinesses, spites and failings, he was himself a large-brained self-educated Titan whose natural field was parliament and whose resources of character and intellect enabled him in his later years to overshadow all his contemporaries. [6]

In his later years, Parkes did not escape scandal. His second wife had been his mistress and had two children by him before the relationship was formalised. On account of this indiscretion, the doors of Government House were closed to him. [7] He raised eyebrows again when he married his 23-year-old housekeeper shortly after his second wife died, against the strong wishes of his closest friends. He died shortly after his third wedding, just before his 81st birthday.

Parkes [media]had 12 children from his first marriage. Five died in infancy and six survived him. He had another five children from his second marriage, one of whom, Cobden Parkes, was the government architect responsible for the design of the Dixson and Mitchell wings of the State Library of New South Wales.

Notes

[1] Henry Parkes, Fifty Years of the Making of Australian History, Longmans, Green, London, 1892, pp 8–9

[2] Henry Parkes, Fifty Years of the Making of Australian History, Longmans, Green, London, 1892, p 1

[3] Elaine Thompson, Fair Enough: Egalitarianism in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1994, p 224

[4] Elaine Thompson, Fair Enough: Egalitarianism in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Sydney, 1994, p 227

[5] AW Martin, 'Henry Parkes', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 5, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1974, p 403

[6] AW Martin, 'Henry Parkes', Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 5, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1974, p 405

[7] AW Martin, Henry Parkes: A Biography, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1980, chs 15 and 16