The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney's first ice

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney's first ice

Saturday 29 January 1855 was [media]hot – the thermometer hit 112 °F (44 °C) [1] but in central Sydney the solution was at hand – ice.[2] The cooling natural ice had travelled from the winter's cold of Boston, USA, as part of the international 'frozen water' trade that had first reached Sydney in 1839.

For six years (1839 to 1840 and 1853 to 1856) it was natural ice that kept Sydneysiders and their food cool during the heat of summer; but the international frozen water trade[3] was finally the victim of a technological development from the Australian colonies – machine-made ice. From 1857 manufactured ice travelled to Sydney by ship from Melbourne, but from 1864 the Sydney Ice Company's works, located on West Street, Darlinghurst, [4] provided a local source, free from the vagaries of transport or weather.

The trade in natural ice played an unrecognised but surprisingly important role in creating the world as we know it today. It started the demand that led to today's omnipresent refrigerators and freezers, ready availability of cool drinks and ice creams, and dramatic improvement in food hygiene. It led to the development of suitable insulated ships that were essential for the development of frozen meat exports, [5] and ultimately to the thermal insulation used in today's modern buildings and appliances.

Ice arrives in Sydney

Imported ice first arrived in Sydney on 16 January 1839, when the barque Tartar arrived at Moore's wharf after a voyage of four months and five days from Boston. [6] It carried 250 tons of ice (although reportedly 400 tons had been sent – the rest melting on the journey), 22 boxes of refrigerators (probably wooden boxes with a layer of insulation and an inner metal lining) and six ice hooks (presumably to help shift the ice). Initially the Sydney Herald reported that the general public had 'no more interest than if the natives skated upon it every winter' [7] but a few days later suggested a statue be erected in honour of the captain, for the 'iced punch, which must have been what the ancients called nectar'. [8]

The entire cargo of ice and an icehouse, which was erected on Moore's wharf, were purchased by Thomas Dunsdon, confectioner of George Street. [9] Ice was available at threepence per pound [10] (450 grams) until 25 March 1839, when the price increased to sixpence per pound due to the 'great waste which has taken place in the ice (amounting to a full three hundred percent)'. [11] It was available in 'nearby' locations, including the Hunter River and at Parramatta, 'by means of the steam-boats'. [12]

Even [media]before the ice had been consumed, Dunsdon had reportedly arranged a further shipment, [13] which arrived on 10 January 1840 on the ship Ceylon, along with 12 boxes of refrigerators. [14] This time, Mr DN Munro made sales from the 'ice house on Moore's wharf' at a cost of 1½ pence per pound, or twopence per pound if delivered 'to persons at their residences in Sydney'. [15] Delivery was available to 'Newcastle, Parramatta, Wollongong, Windsor, and Liverpool' in packages from 56 pounds (½ hundredweight) to two hundredweight (25.4 to 101.6 kilograms) at threepence per pound, with payment 'Cash on delivery'. [16] The ice lasted until about 14 February 1840, when the warm weather resulted in a failure of supply, or as the Sydney Gazette announced,

A wag informed us that the crew of the Ceylon had been employed for two days in pumping out the ice which the sudden change in atmosphere had turned into lukewarm water. [17]

Although the American ice businesses continued to promote their product, notably with regular newspaper reports, [18] no evidence has yet been found for further ice imports into Sydney in the period from 1840 to 1852. But in 1853, both newspaper reports and import statistics once again reveal American ice imports.

The trade revives

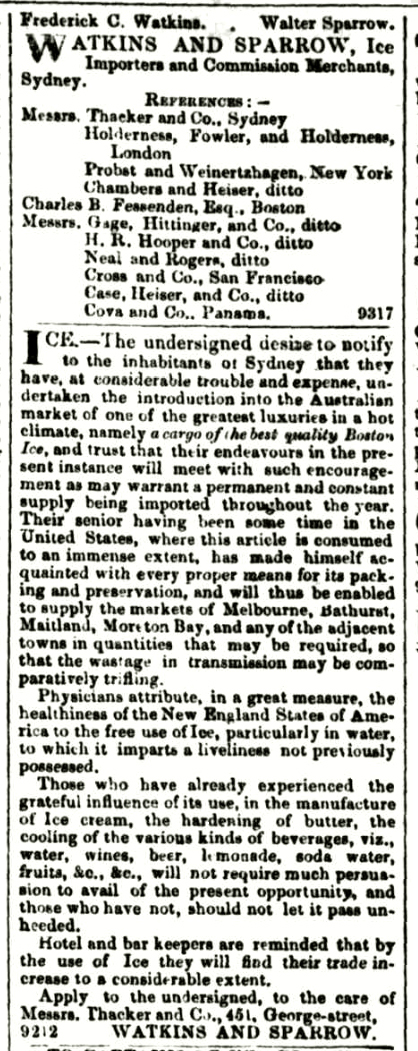

On 10 March 1853, [19] the ship Monterey arrived 115 days [media]after leaving Boston. [20] Its cargo included 26 boxes of refrigerators, two boxes of ice tools and 366 tons of ice. In advertisements, the use of ice promised a range of benefits to the people of Sydney:

Physicians attribute, in a great measure, the healthiness of the New England States of America to the free use of Ice, particularly in water, to which it imparts a liveliness not previously possessed. [21]

Frederick C Watkins and Walter Sparrow purchased the Monterey ice, initially selling it from the premises of Thacker and Co at 451 George Street. From 8 to 23 April 1853, the ice was being sold from the icehouse on Moore's wharf at 3½ pence per pound for over a hundredweight (50.4 kilograms), and 4½ pence per pound for smaller amounts, with Watkins and Sparrow having moved to their own premises at 700 Lower George Street. [22] From 27 April 1854, the advertisement included the option of delivery – but at sixpence per pound, [23] with the last advertisement that autumn on 5 May 1853.

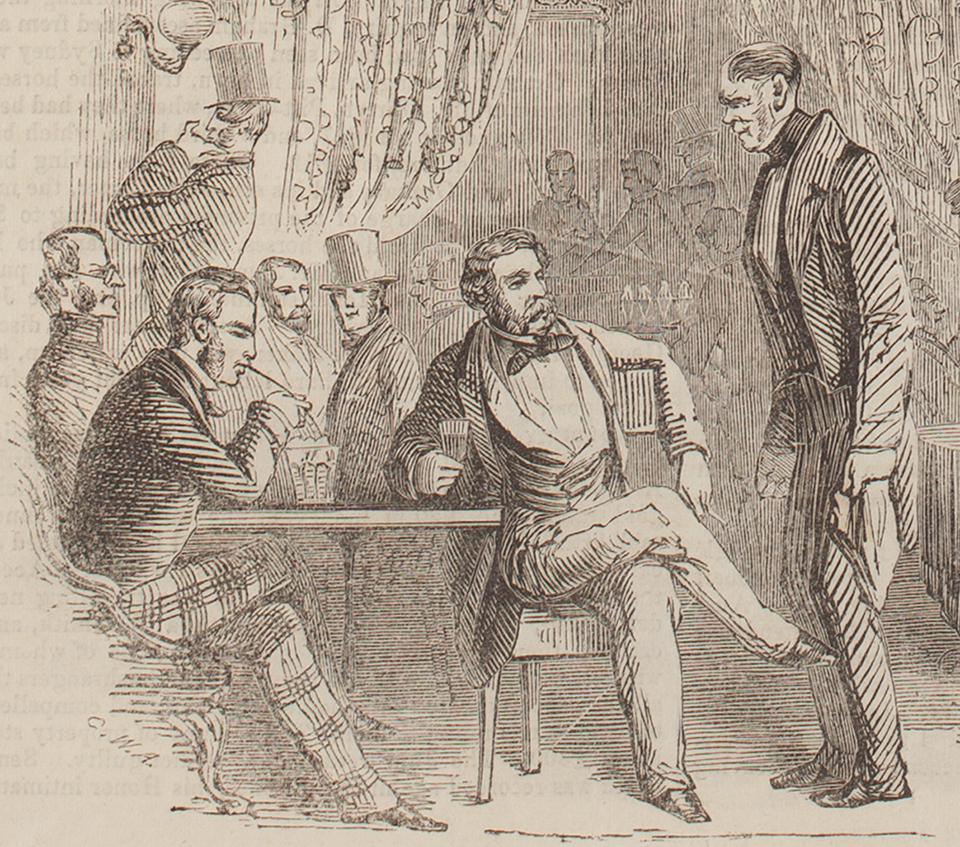

The ice apparently remained viable in the icehouse over the winter of 1853; on 28 October 1853 Watkins and Sparrow resumed their advertising, although the price had increased to sixpence per pound, picked up from their new depot at the John Bull Inn, King Street (near Pitt Street). [24] It was not until 6 December 1853 that the Queen of the Seas arrived from Boston with a load of 353 tons of ice. [25] The now-assured availability of ice led to the promotion of iced drinks: 'Iced sherry cobblers; Iced brandy smashers; Iced lemonade; Iced Soda water.' [26] Sydney even started to export ice to Victoria – for example, on 21 December 1853 the ship London took 12 cases of ice to Melbourne. [27]

The summer of 1853–54 was not successful for ice sales. On 8 January 1854 the ship Magnolia had brought 378 tons of ice from Boston to Melbourne, [28] but on its departure it called into Sydney where in addition to the remaining 150 tons of ice from its original cargo, it transhipped a further 100 tons from the Queen of the Seas. [29] After a voyage of 73 days, the Magnolia arrived in San Francisco, [30] in the height of the northern hemisphere summer where presumably the ice once again had value – albeit at least a year and a half since it was cut from the frozen lakes near Boston. This lack of interest in the ice was possibly the cause of the event mentioned in the reminiscences of Dr JC Cox (1834–1912), a leading Sydney physician, to a meeting in his honour at the Australian Club. He recalled that as clubs and hotels had never used ice, the shipment was unloaded into a quarry at the east side of Circular Quay and left to melt. [31]

The Watkins and Sparrow partnership was dissolved on 10 March 1854, [32] and Sparrow departed Sydney on 10 June 1854 on the schooner Matchless for Honolulu. [33]

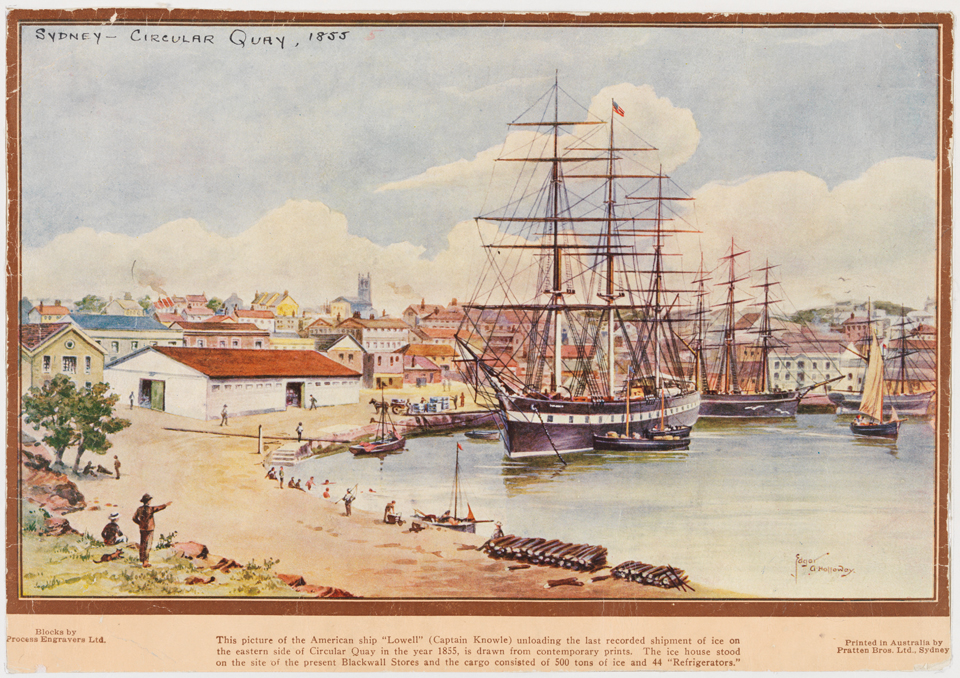

1855 brought a new [media]shipload of ice, new agents and a new interest in the use of ice. On 12 January 1855 the ship Lowell arrived in Sydney [34] after a voyage from Boston of 128 days, and landed 491 tons of ice and an icehouse. [35] Rawack Brothers and Co became the agents selling ice from 'Vernon Lake' – but no location of this name has been found near Boston, so the true source is unclear. Messrs Alexander Campbell and Co were awarded land 'at a merely nominal rent' near Circular Quay [36] and the new icehouse was soon erected at a cost of £800. [37] The ice was sold from the ship at the Circular Quay wharf for threepence per pound above a hundredweight, fourpence per pound under a hundredweight [38] – which assuming no losses at dock, means the cargo would have sold for at least £13,000.

That [media]summer was hot, and the ice had arrived at just the right time. John Poehlman's Café on George Street used 25 hundredweight (1270 kilograms) of ice serving 'sherry cobbler, ice cream, mint juleps and brandy smash', [39] as the thermometer was hitting 112 °F (44 °C). [40] Iced drinks were soon available at other establishments – including the Liverpool Arms (Pitt and King streets) and Victoria Hotel (Pitt Street). [41] As well as serving Sydney, supplies of ice were sent to Melbourne. [42]

The ice trade does not seem to have been without its financial issues, for by 19 March 1855 Henry Hockings, at that time a trader but later to become very involved in the development of the local wine industry, [43] had taken over sales, working from an office in Poehlman's Café Française, George Street (opposite Hunter Street) while supplies continued to be available from the icehouse, [44] with advertising continuing until 30 April 1855.

[media]On 7 January 1856 the Philomela , from Boston, arrived with 383 tons of ice, [45] reportedly from Wenham Lake. John Poehlman now took over sales, arguing that reasons for earlier failures were the lack of a 'well arranged plan for its distribution' and the belief that ice was 'a very difficult article of domestic use to keep'. The use of a 'tin in a box surrounded with saw-dust or powdered charcoal' was recommended to keep a piece of 12 pounds (5.4 kilograms) for two days. [46] The continued use of the icehouse for storage and sales suggests this ice was from the same supplier as in 1855, even though the source lake seems to have changed.

Poehlmann's success led quickly to a second 1856 shipment of 529 tons, which arrived on the ship Oriental on 19 June 1856. [47]

The Oriental also carried possibly Australia's first import of chilled fruit. The 40 half barrels and 20 full barrels of American Pippin apples were 'packed as gathered from the tree, and stowed in the Cargo of Ice', and were sold by A Campbell Brown at his auction rooms at 232 George Street on 26 June 1856. [48]

Newspaper advertisements for the selling of ice commenced on 21 October 1856 [49] and were carried through until 10 November 1856. While prices had fallen, the distribution network was well in place:

Ice will-be supplied at the Ice House at 2 ½d per lb for quantities of 100 lbs weight and upwards; 3d for quantities under 100 lbs; and will be delivered from the cart at houses in town for 3½ d and 4d per lb, according to quantity, and in the suburbs at 4d and 5d according to distance. [50]

Sydney's icehouse

The City of Sydney Bourke Ward Assessment Books for 1858, 1861 and 1863 record Buchanan Skinner & Co as the owners of a single-storey, shingle-roofed, wooden icehouse. [51] The Historical Atlas of Sydney includes maps for 1855 and 1865, which suggest the icehouse was located at the corner of Bligh and Bent streets. [52]

The wooden icehouse had double walls, with the space between filled with sawdust, [53] and unsurprisingly was highly inflammable. It was destroyed by an accidental fire which was discovered at 11 pm on Friday 22 May 1862 and although two engines from the No 2 Volunteer Company and one engine from the insurance companies were quickly on the scene, the fire destroyed the entire building. [54] The building was reported as having been unoccupied for some time, [55] matching the import statistics.

End of the frozen water trade

Suddenly the Sydney ice trade with Boston stopped, not because of a fall in interest in ice, but because advances in technology permitted the manufacture of ice closer to home.

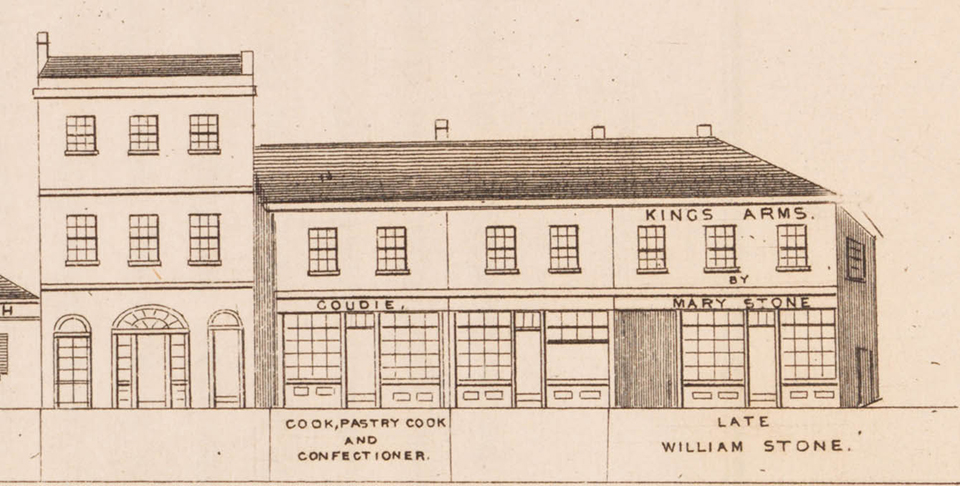

Sydney-made ice was available as early as 1848. 'Robinson's celebrated freezing machine', patented by Thomas Masters in 1843, used the heat absorption of a chemical mixture to create ice, but required new chemicals each time ice was made. [56] In December 1848, Thomas Goudie,[media] confectioner, of 284 Pitt Street, [57] Thomas Robinson, hairdresser, of George Street, [58] and William Blyth, of the Victoria Refreshment Rooms in Pitt Street, [59] advertised the availability of ices, iced lemonade, other draughts and 'small quantities of raw ice' frozen from pure water daily. By December 1849 these advertisements had stopped, suggesting the production was uneconomic, and by 1853 American ice imports had again commenced.

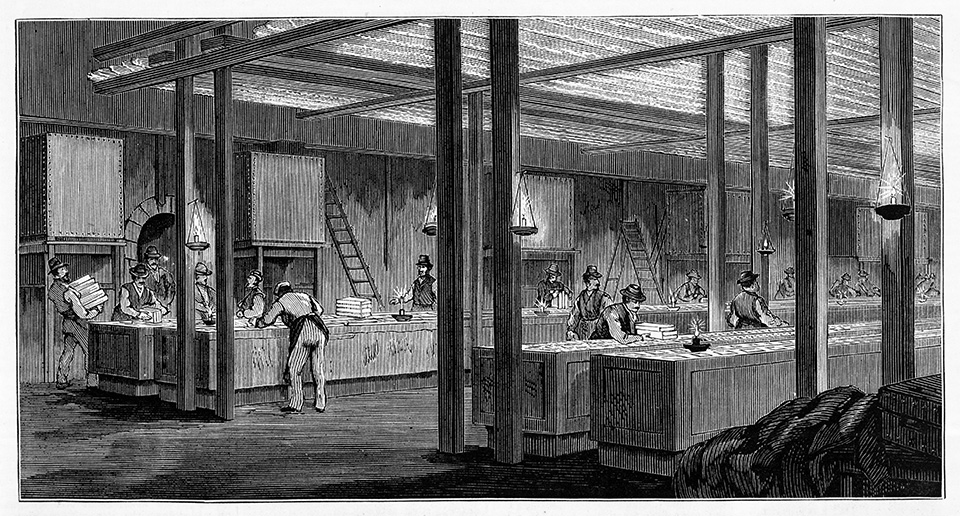

Lower [media]cost ice was only possible by non-chemical means, and this was the approach taken by James Harrison of Geelong, Victoria. Harrison improved an 1834 British design for vapour-compression refrigeration, and in 1851 installed a prototype machine for a brewery in Bendigo, using ether as the refrigerating medium. [60] Harrison's ice-making machine was manufactured by PN Russell and Co of Sydney, and initially supplied to Melbourne, Bendigo, and Adelaide.

By 1858 ice was being manufactured in Melbourne, possibly by 'The Patent Ice Company', a partnership of James Harrison and John Henry Brooke, [61] and exported around the Australian colonies. [62] In a circular twist of history, on 26 January 1858, seven boxes of ice were sent from Melbourne to Sydney on the ship London. [63]

By December 1860 Harrison and Russell had formed the Sydney Ice Company, [64] [media]spending nearly £3000 on their own machine, possibly designed by the young PN Russell engineer Norman Selfe, and started the commercial supply of locally made ice. [65] Using Botany water, the local ice was 'both in respect of purity and hardness, full equal to that imported from North America'. Twice-weekly deliveries of 15 pounds of ice cost 21 shillings a month. [66] Harrison was bought out in 1862, [67] but the manufactured ice industry had begun.

Wenham Lake ice

The international frozen water trade traces its origins to a Frederick Tudor, who started exporting ice from Wenham Lake, near Boston, Massachusetts in 1804. Although his business suffered many trials, by the 1840s it was successfully shipping ice around the world. David Henry Thoreau in his 1854 book Walden, or life in the woods described the arrival of 100 men to 'take off the only coat, ay, the skin itself of Walden pond in the midst of a hard winter' [68] – an intrusion of the modern industrial world in his isolated haven.

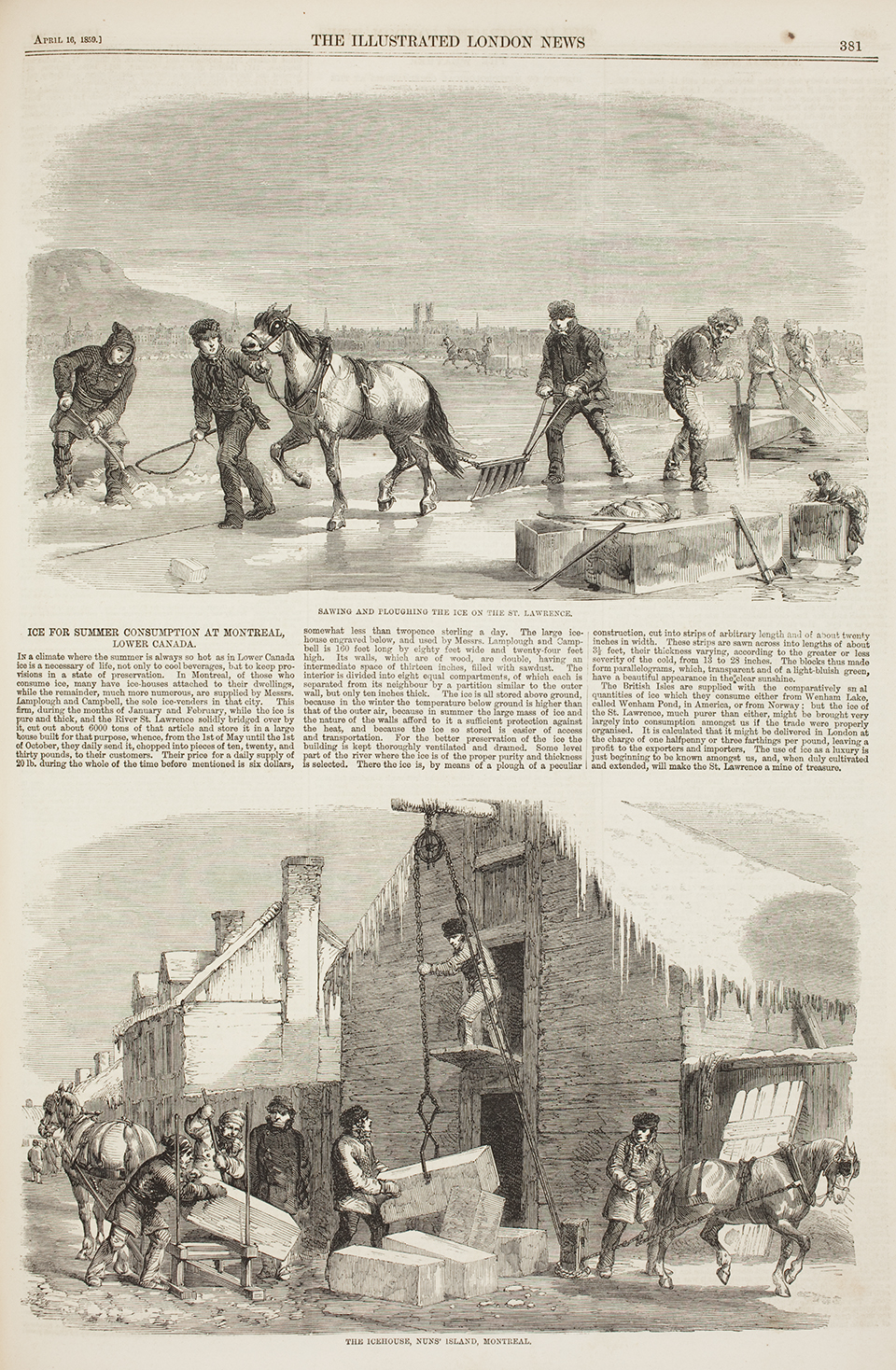

The ice that cooled the hot Sydney summer of 1839 was most likely cut about a year earlier from the frozen lakes near Boston, Massachusetts, then transported by land to the port, loaded into insulated ships and carried to Sydney. [69] The ice was promoted as being from Wenham Lake, but this trade name hid the real sources at a number of lakes, including Walden. [70] The ice companies were great at marketing, with newspapers around the world being provided with stories – long before the ice was actually available in the country. Queen Victoria developed a taste for Wenham Lake ice, and the company became suppliers 'by appointment'. [71]

The transport of this ice around the world was achieved without any artificial refrigeration. The large volume of ice minimised the exposed surface area and hence melting, but the critical technological development was well-insulated ships. Timber, peat, straw and sawdust were used with a triple-walled hull to insulate the cargo [72] – turning waste products into valuable commodities, and increasing the profitability of Boston's sawmills and farms. [73]

Consequences of the international ice trade

Although the import of ice from America into Sydney lasted a comparatively short time, the benefits were ongoing – in particular supporting the development of the frozen meat trade and the introduction of salmon to Australia.

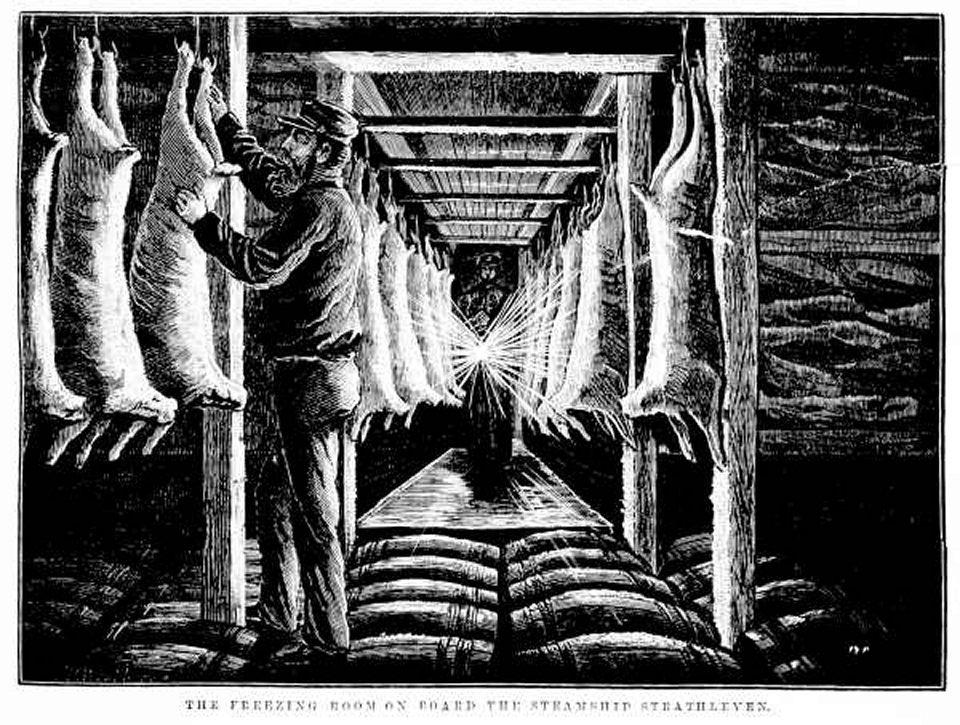

The frozen [media]meat trade is often considered to be built on four main conditions: meat was available, there was a market for the meat, suitable refrigeration technology existed, and entrepreneurs were willing to establish a new business. [74] But without the experience of transporting natural ice long distances by ship, the Australian frozen meat trade could not have begun. Although natural ice was the first refrigerant for the meat trade between Canada, American and Europe, Australian meat exports used artificial refrigeration, from the first export from Sydney to London on the insulated SS Strathleven in 1879. [75] The thermal insulation knowledge was also important in developing thermal insulation for buildings.

Natural ice also permitted the introduction of salmon to Australia. Although it had been long recognised that shipping salmon ova (eggs) from Britain through the tropics would be problematic, an attempt was made as early as 1860, using 15 tons of Wenham Lake ice to provide an on-board, cool, freshwater pond. [76] This failed, as did a second attempt in 1862, [77] but the lessons learnt supported a third successful attempt in 1864, based on transporting the ova on a bed of moss surrounded by ice, [78] starting the Tasmanian salmon fishery industry.

References

Keith Farrer, To feed a nation: a history of Australian food science and technology, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic, 2005

Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade: how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001

Notes

[1] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1855, p 4

[2] Acknowledgements to Rachel Grahame for research in Sydney. Import and export statistics are from 'Statistics of NSW'. Newspapers from National Library of Australia 'Trove' http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper

[3] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade: how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001, p xxi

[4] Sand's Sydney Directory, 1864, p 216

[5] Keith Farrer, To feed a nation: a history of Australian food science and technology, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic, 2005, p 53

[6] Sydney Herald, 16 January 1839, p 2

[7] 'Domestic Intelligence', Sydney Herald, 21 January 1839, p 2

[8] Sydney Herald, 8 February 1839, p 2

[9] The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 9 February 1839, p 2

[10] Sydney Herald, 18 February 1839, p 3; 25 February 1839, p 1; 8 March 1839, p 1; 11 March 1839, p 1

[11] Sydney Herald, 25, 29 March 1839, p 3

[12] Sydney Herald, 21 January 1839, p 2

[13] The Australian, 9 February 1839, p 2

[14] Sydney Herald, 10 January 1840, and The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 14 January 1840, p 2

[15] Sydney Herald , 22, 31 January, 3 February 1840, p 1

[16] Sydney Herald, 3 February 1840 p 3. The same advertisement also appeared on p 1 on 5, 6, 7, 10 & 12 Feb and p 2 on 14 Feb 1840

[17] Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 13 February 1840, p 2

[18] For example. The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 10 March 1847, p 4

[19] ' Shipping Notices', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1853, p 2

[20] 'Shipping News', Sydney Morning Herald, 21 March 1853, p 2

[21] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 March 1855, p 3; Advertisements (repeated each day for the rest of that week and the following week)

[22] Sydney Morning Herald, 8 April 1853, p 3, Advertisements (repeated 9, 12, 13, 20 & 23 April)

[23] Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 1853, p 1; Supplement: Advertisements (repeated each day for the rest of that week and then to Thursday 5 May the following week)

[24] Sydney Morning Herald, 28 October 1853, p 3, 2 Nov 1853, p 6, 2 December 1853, p 2

[25] ' Shipping Notices', Sydney Morning Herald, Wed 7 December 1853, p 4

[26] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 December 1853, p 5

[27] Sydney Morning Herald, 22 December 1853, p 4

[28] 'Melbourne Arrivals', Sydney Morning Herald, 14 January 1854, p 2

[29] 'Exports', Sydney Morning Herald, 8 April 1854, p 4

[30] ' Shipping Intelligence', Sydney Morning Herald, 13 September 1854, p 2

[31] Sydney Morning Herald, Tues 1 October 1912, p 12; a letter to the editor from Edward Stace (or Stack) in Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October 1912 p 10, suggests this dumping of ice occurred in 1855, but in 1855 Cox was probably in Edinburgh, although he was in Sydney for the earlier arrival of ice.

[32] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 March 1854, p 2, Advertisements

[33] Sydney Morning Herald, 12 June 1854, p 4, Advertisements

[34] ' Shipping notices', Sydney Morning Herald, 12 January 1855, p 4

[35] ' Shipping Intelligence', Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 17 January 1855, p 2

[36] Sydney Morning Herald, 24 January 1855, p 8

[37] 'The Late Fire', Sydney Morning Herald, 28 May 1862, p 4

[38] Sydney Morning Herald, 29 January 1855, p , Advertisements

[39] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1855, p 4

[40] Sydney Morning Herald, 30 January 1855, p 4

[41] Sydney Morning Herald, 1 February 1855, p 8

[42] For example, Argus, 12 February 1855, p 4, ' Imports 10 Feb - City of Sydney from Sydney 1 case ice';Argus, 21 February 1855, p 4, 'Imports 20 Feb Wonga Wonga from Sydney 1 case ice.'

[43] 'Commercial pioneer', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 October 1912, p 7

[44] Sydney Morning Herald, Advertisements, 19 March p 6, 24 March p 2, 31 March p 8, 2 April p 6, 7 April, p 6, 9 April, p 6, 19 April, p 6, 30 April 1855, p 6

[45] 'Shipping', Sydney Morning Herald, 8 January 1856, p 4

[46] 'Importation of Ice', Sydney Morning Herald, 15 Feb 1856, p 4

[47] Sydney Morning Herald, 20 June 1856, p 4

[48] Sydney Morning Herald, 26 June 1856, p 4

[49] Sydney Morning Herald, 21 October 1856, p 8

[50] Sydney Morning Herald, 10 November 1856, p 2

[51] City of Sydney Assessment Books (CRS17 transcripts: 1858 p 18; 1861 p 11; 1863 p 16), at www.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/AboutSydney/HistoryAndArchives/Archives/ServicesForResearchers/AssessmentBooks00.asp

[52] Historical Atlas of Sydney – City of Sydney Archives. City Detail Sheets, 1855; Trigonometrical Survey of Sydney, 1855-1865, available online at http://www3.photosau.com/CoSMaps/scripts/home.asp. Icehouse located in 1855 map on sheet 4 & 1865 map on sheet D1; In a letter in Sydney Morning Herald, 9 October 1912 p 10, Edward Stace (or Stack?), reports 'I have in my possession a picture showing the icehouse on the Quay.'

[53] 'The Late Fire', Sydney Morning Herald, 28 May 1862, p 4

[54] 'Fire At The Circular Quay', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 May 1862, p 4

[55] 'Fire At The Circular Quay', Sydney Morning Herald, 24 May 1862, p 4; 'The Late Fire', Sydney Morning Herald, 28 May 1862, p 4

[56] Clifton Cleve, Book Of Inventions, Henry Hurst, London, 1848

[57] Sydney Morning Herald, 13 December 1848, p 3

[58] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 1848, p 1

[59] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 December 1848, p 1

[60] George Wilkenfeld and Peter Spearritt, Electrifying Sydney – 100 Years of EnergyAustralia, EnergyAustralia, Sydney, 2004, p 11, available online at http://www.ausgrid.com.au/Common/About-us/~/media/Files/About%20Us/ElectrifyingSydney100Years.ashx, viewed 11 July 2011

[61] ' Dissolution of Partnership', Government Gazette (Victoria) 122, 2 October 1860

[62] This is based on the Port of Melbourne 'Imports and Export for the week ended ...' provided in the Argus; there are exports of ice from Melbourne, but no imports, for example Argus, 28 September 1858, p 4 (week ended 18 September); or Argus, 24 January 1859 (week ended 15 January), plus the various individual ships which included exports of ice but not imports. Last ice import from USA found 8 December 1856.

[63] Argus, 26 January 1858, p 4

[64] See LG Bruce-Wallace, 'Harrison, James (1816–1893), Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol 1, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1966, available online at http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/harrison-james-2165, viewed 11 July 2011

[65] Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1860, p 2; George Wilkenfeld and Peter Spearritt, Electrifying Sydney - 100 Years of EnergyAustralia, EnergyAustralia, Sydney, 2004, p 11, available online at http://www.ausgrid.com.au/Common/About-us/~/media/Files/About%20Us/ElectrifyingSydney100Years.ashx, viewed 11 July 2011

[66] 'Harrison's Ice Making Machine', Sydney Morning Herald, 28 December 1860, p 5

[67] Keith Farrer, To feed a nation: a history of Australian food science and technology, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic, 2005, p 52

[68] Henry David Thoreau, Walden, available online at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-h/205-h.htm, viewed 12 January 2011

[69] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade : how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001

[70] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade : how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001, p 135

[71] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade : how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001, p 140

[72] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade : how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001, pp xix, 29, 44, 90

[73] Gavin Weightman, The frozen water trade : how ice from New England kept the world cool, HarperCollins, London, 2001, p 175

[74] Ian Arthur, 'Shipboard refrigeration and the beginnings of the frozen meat trade', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, vol 92 no 1, June 2006, pp 63–82

[75] Keith Farrer, To feed a nation: a history of Australian food science and technology, CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, Vic, 2005, p 54

[76] Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, 26 May 1860, p 4; Sydney Morning Herald, 18 May 1860 p 2

[77] Sydney Morning Herald, 7 August 1862, p 8

[78] Sydney Morning Herald, 18 April 1864, p 4