The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Hunters Hill

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Hunters Hill

The first colonists who came to Sydney in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries had come from crowded industrial cities in Britain. It is therefore not surprising that a particular suburban ideal began to emerge here, the 'Australian dream', of a house of one's own, set in its own grounds. By the twenty-first century that ideal was challenged by population pressure and economic factors, yet the Sydney suburb of Hunters Hill remains largely intact, and historically important, as the oldest surviving example of the ideal.

The area was sighted by Captain John Hunter when he charted Sydney Harbour in January and February 1788, promptly after the arrival of the First Fleet; Hunters Hill derives its name from Hunter. [1] A high, rugged peninsula, at that time thickly covered with turpentine trees, ironbark, eucalypts, white stringybark, and bloodwood, it is bounded by water on two sides, the Lane Cove and Parramatta rivers. When Hunter made his survey in 1788, this land was the eastern limit of the Aboriginal people of the Ryde district, the Wallumategal, who may have known the peninsula as Moco Boula, meaning 'two waters.' [2] In his journal, Hunter took careful note of the Aboriginal shelters, made out of 'a soft crumbly sandy stone', and observed that some caves 'would lodge 40 or 50 people.' [3] By the 1830s, when the first white settlers came into the area, the Aboriginal people had died from smallpox or been driven from their land. To this day, however, archaeological sites remain in pockets of bushland and undeveloped stretches of foreshore in Hunters Hill. Axe-grinding grooves, rock engravings, hand stencils and middens are reminders of the area's Indigenous Australians. [4]

Early grant holders

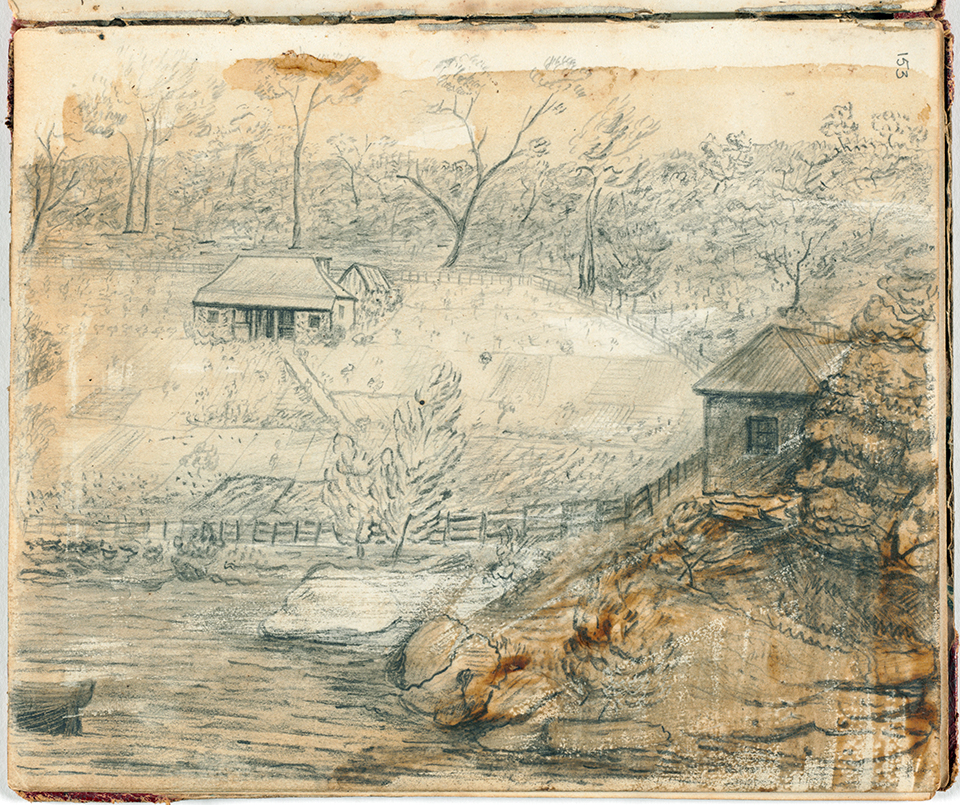

In the 1830s many of those who were granted or who purchased land in Hunters Hill were shady customers, exhibiting the combination of enterprise and criminality that flourished in the early years of the colony. John Tawell – forger, ex-convict, Sydney's first chemist, exporter of whalebone, zealous Quaker, and murderer – took the prize for notoriety. [5] The most respected of the early landowners was the emancipist Mary Reibey (1777–1855), one of the most astute business people in the colony of New South Wales. In 1835 she bought 60 acres (24 hectares) of land and soon expanded her holding to 110 acres (45 hectares), which sloped down to the Lane Cove River (Reiby Road indicates the area today). [media]She called it Figtree Farm after a large Port Jackson fig tree nearby and used it as a country retreat from Sydney. She rented it for three years to the artist Joseph Fowles (1810–78), whose unpublished journal of 1838 contains detailed descriptions, the earliest we have, of the natural environment of the peninsula. [6]

A retreat from the city

The 1840s saw the arrival of entrepreneurs, who saw the suburban potential of Hunters Hill. It was a wooded peninsula accessible to the city but, at the same time, a rather private cul-de-sac in the harbour, and its high ridge with a thoroughfare along the top was ideal for houses overlooking the water, on either side. These early pioneers began quarrying the abundant local sandstone for building, and from the 1840s to the 1880s Hunters Hill developed as a residential retreat from the city. [media]While today most buildings are of brick, with some of timber, the early stone constructions – cottages, larger villas, public buildings, stone walls, and stone steps leading steeply down to the foreshores – are distinguishing features of Hunters Hill. Besides this built environment, the natural environment is characterized by blue water glimpsed through trees, outcrops of sandstone, and areas of native bushland, together with abundant plantings favoured by the European settlers, such as palms, bunya pines, giant strelitzia, and camphor laurels.

The French settlement

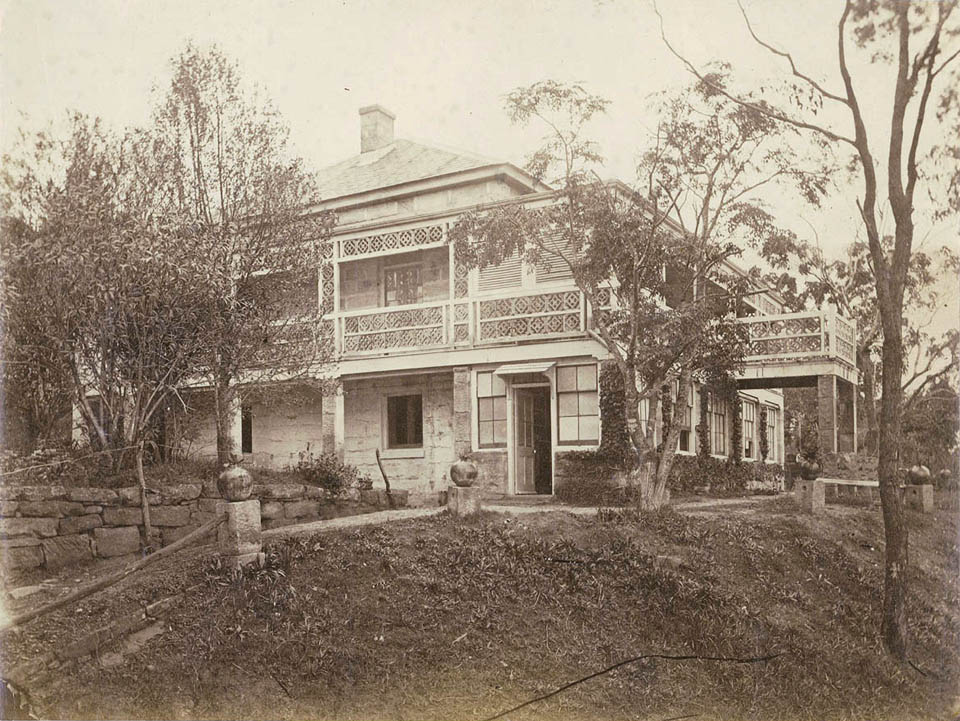

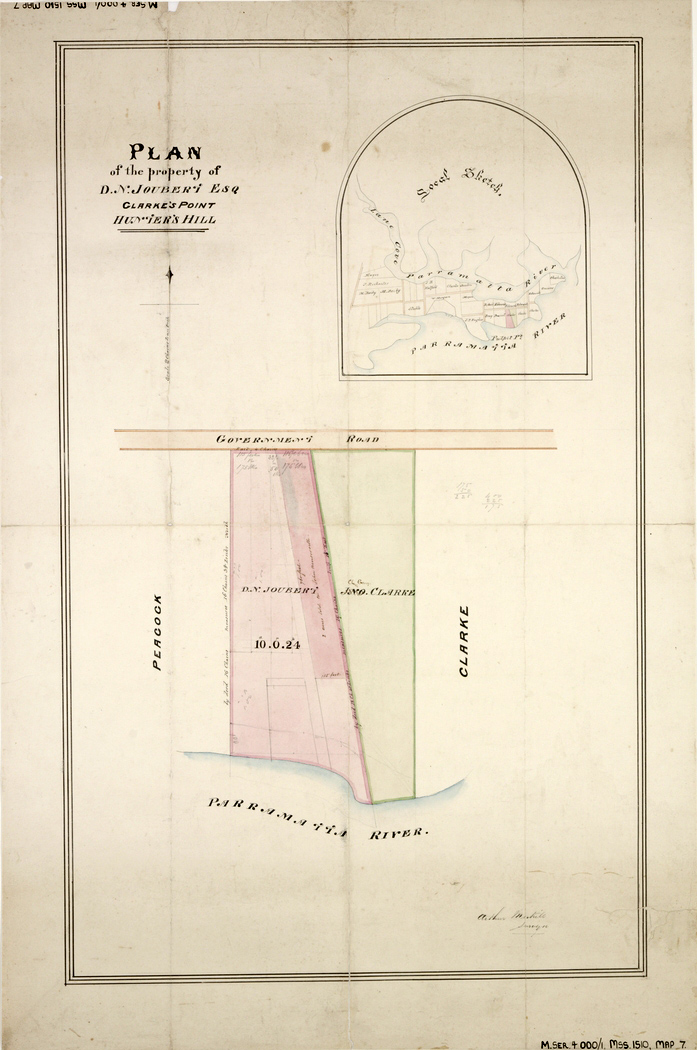

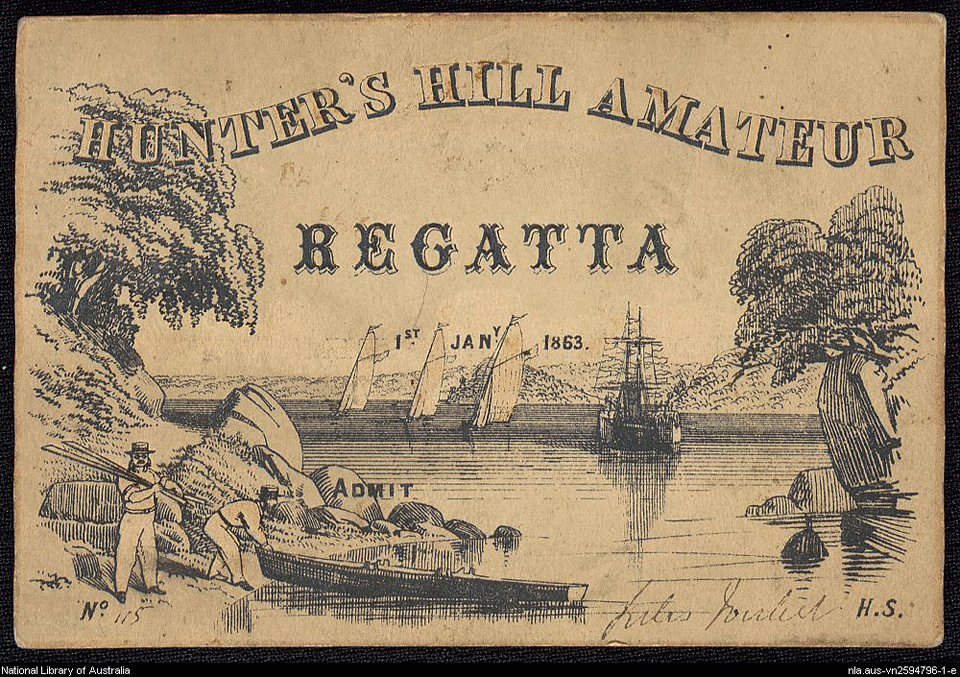

The [media]creation of the suburb in the nineteenth century was influenced by an unusual number of colonists from continental Europe. [7] Most eminent were the Frenchmen – Didier Joubert (1816–81) and his brother Jules (1824–1907), who migrated to Australia from the Bordeaux area of France in the 1830s. They were joined by a number of their compatriots, such as Count Gabriel de Milhau, a disaffected nobleman exiled from France for his part in the 1848 revolution, and the entrepreneurial Leonard Etienne Bordier. Didier Joubert, a wine and spirit merchant who ran a business in Sydney town, settled in Hunters Hill in 1847. He purchased Mary Reibey's Figtree Farm, and once his brother Jules joined him in 1854, they began building sandstone villas and laying out subdivisions. Jules was responsible for the most successful of the early subdivisions, the area of Ernest and Ady streets from Alexandra Street to the Lane Cove River. In 1859 he subdivided it into 26 allotments of varying size, the smaller fronting Alexandra Street, the larger towards the river as sites for marine villas. They were sold and built on in the 1860s and 1870s. The most notable of the Joubert houses is Passy at 1 Passy Avenue, named after the precinct of Passy in Paris and built in 1855–56 as the residence of the French Consul to Sydney. It became a symbol of the French origins of Hunters Hill. In 1858 the Sydney Morning Herald, [media]reporting on a New Year's Day regatta on the Parramatta River, noted that the tricolour flew from the roof of Passy and that

Hunter's Hill is looked upon as almost a French settlement, whilst on the land opposite, on the southern shore, is located a society of French clergymen, designated the French Mission. [8]

The French clergy were the Marist Fathers, who operated a mission in the South Pacific islands from the 1830s. In 1847, with the help of Didier Joubert, they purchased a house at Hunters Hill as a place to keep their stores and as a rest and recuperation centre for their missionaries; they named it Villa Maria. The Marist Fathers sold the house in 1864, moved to Mary Street, and transferred the name Villa Maria to the stone monastery and church they built there. The original stone house, now known as The Priory, still stands at the head of Tarban Creek.[media] In the 1870s, the Marist Brothers joined the Fathers in Hunters Hill and established their school, St Joseph's College on Ryde Road. The school building, constructed over a period of time from 1882–1904, is one of the finest sandstone buildings in the suburb. The French Marist Sisters also came to Hunters Hill and in 1908 established a high school for girls on Woolwich Road.

Besides the Joubert brothers, the most productive of the early pioneers was Charles Edward Jeanneret (1834–98). Despite his Gallic name, he was Australian-born of French Huguenot descent, and was listed among the Australian Men of Mark in 1888 as 'one of the successful among the native-born of New South Wales.' [9] [media]He settled in Hunters Hill in 1857 and began a speculative building program which continued until 1895. Like the Jouberts, he purchased land, made subdivisions, and financed the construction of stone houses. The Aboriginal name 'Wybalena' meaning 'resting place' is derived from Tasmania, where Jeanneret's father had worked as a doctor. It had a special significance for the family and today the 'Jeanneret precinct' is centred on Jeanneret's original Wybalena Estate and includes two of his own residences – Wybalena at 3 Jeanneret Avenue, built in 1874 and the smaller Wybalena at 22 Woolwich Road, built in 1895, with the name on both front gates – as well as Wybalena Road. [10]

Italians and Irish

A second group of European settlers who contributed substantially to the creation of the early suburb were Italians. In 1855–56 hundreds of immigrants from the north of Italy and Italian-speaking areas of Switzerland came to Sydney, and some settled in Hunters Hill and worked as stonemasons. As entrepreneurs like the Jouberts and Jeanneret were establishing their building programs, the expertise of these Italian stone masons was invaluable, and they were employed to construct houses, public buildings, and boundary walls. Closely associated with them was John Cuneo (1825–84), a supporter of Garibaldi who migrated to Australia from Genoa in 1854 and became a prominent business man in Hunters Hill. During 1861 and 1862, Cuneo built the suburb's first hotel, The Garibaldi. Though now used for offices and shops, The Garibaldi still stands prominently on the corner of Alexandra and Ferry streets, a golden stone building with a classical Italian sculpture in a niche above the door. Of all the Hunters Hill buildings, it is the most evocative of the Italian past.

In sharp contrast to the wealthy landowners, a number of Irish emigrants came to Hunters Hill in the 1850s. The earliest left Ireland at the time of the potato famine, coming with nothing, and yet they contributed to the making of the suburb by working in the quarries and on the construction of roads, walls, and ferry wharves, and by forming a close-knit community with the Marists. The O'Donnells – James, Ann, and their brother Michael – were among the first of these Irish settlers. James worked as a quarryman and Michael sponsored numerous Irish immigrants. Ann married a German shoemaker, John Hellman (later changed to Hillman), and in 1871 they built a cottage of local stone at 38 Alexandra Street, naming it Carrum Carrum after a village in Ireland. More Irish came in the 1870s, among them Felix Cullen, who bought the Mount Leitrim Estate (bounded by Mount, Alexandra, Ferdinand, and Madeline streets), subdivided it, and built houses for sale or rent. He also built a large brick boarding house known as The Gladstone, complete with iron lace. Today it is a landmark on the corner of Mount and Alexandra streets, comparable to The Garibaldi on the corner of Alexandra and Ferry streets.

Some of the quarrymen and stone masons who were employed on the large villas and public buildings also built small independent cottages. Fifty-two such cottages have been identified, the largest collection in Sydney. [11]

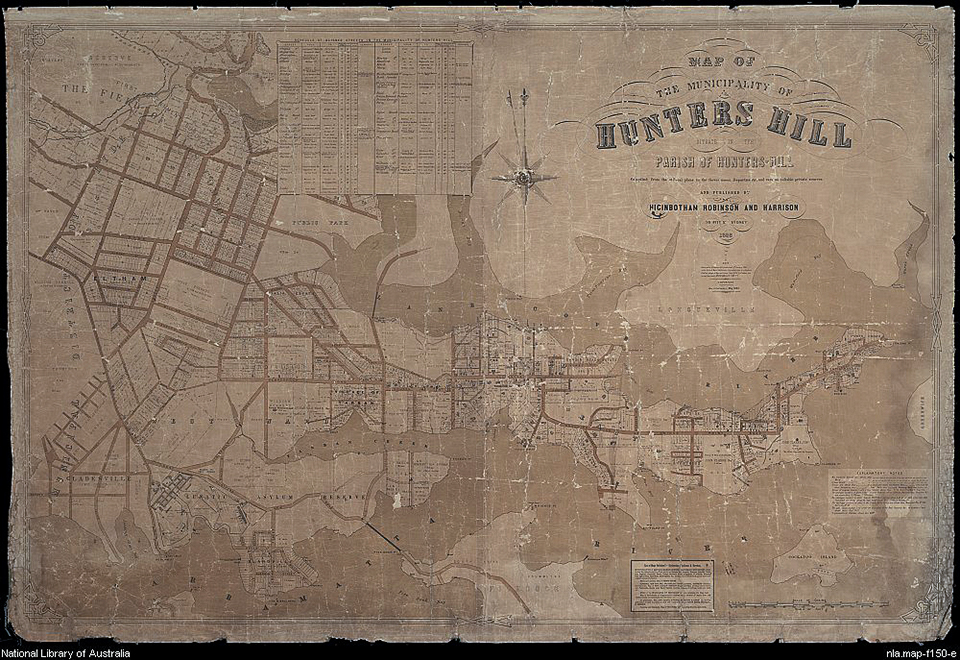

A municipality and a town hall

[media]The year 1861 marked a milestone in the history of the suburb, with the establishment of the municipality of Hunters Hill. A Town Hall in Alexandra Street was completed in 1866. The original boundaries of the municipality remain essentially unchanged today, and take in Woolwich, Boronia Park, Huntley's Point, and parts of Gladesville. The pioneering developers and builders actively participated in the council. Jules Joubert was elected as the first chairman from 1861–62 and his brother Didier was the first official mayor 1867–69. Charles Jeanneret held the office of mayor three times and served as an alderman for 30 years between 1863 and 1893, with the exception of 1881 and 1888, when he was a member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly.

[media]A prime concern of the council was to make life in the suburb more viable by improving transport to the city. The Jouberts operated a ferry service on the Lane Cove side and Jeanneret on the Parramatta side, and the council expanded the ferry services so that by 1886 there were at least 13 wharves in the municipality. In addition, the councillors campaigned strenuously for bridges to be built over the Lane Cove and Parramatta rivers. The first Gladesville Bridge over the Parramatta River was completed in 1881 and the Figtree Bridge over the Lane Cove River in 1885. Hunters Hill also owes its exceptional heritage of trees to the vision of those early councillors. In 1870, under the direction of Mayor Jeanneret, the council introduced a tree policy, planting avenues of trees and giving away trees to residents on the proviso that they be planted near the street frontages. The 1882 Gibbs, Shallard & Co Illustrated Guide to Sydney, the Picturesque Atlas of Australasia (1886) and the Sydney Mail in 1890 all reported enthusiastically on the gardens and tree-lined streets of Hunters Hill. [12]

Living at Hunters Hill

Many diverse residents contributed to the character of Hunters Hill. There were those who worked within the suburb – teachers, dairy-keepers, butchers, bakers, gardeners, clergy, and domestic servants – as well as residents who travelled to the city to work. While Hunters Hill is today mainly the preserve of business and professional people, the nineteenth-century suburb was socially more diverse and class-divided. Even in 1915, those who lived on the higher ground of Hunters Hill considered that 'we of the Hill' were a class above the residents of Woolwich at the eastern end of the peninsula, where a considerable amount of maritime industry continued into the twentieth century. [13] Here, some mention should be made of the FitzGerald family. Robert D FitzGerald (1830–92) was a skilled botanist and artist and author of the monumental Australian Orchids (published in parts 1875–94). He had migrated from Ireland and made his home in Hunters Hill from 1871. His family remained there. About 1945, his son Robert D FitzGerald wrote his (unpublished) 'Reminiscences', a unique and valuable account of the early harbourside suburb, and his grandson, Robert D FitzGerald (1902–87), became a major Australian poet whose works include some fine Hunters Hill poems. [14] Especially during the first half of the twentieth century, an unusual number of writers, including FitzGerald, lived in the suburb. [15]

The early [media]twentieth century suburb was described by Doris Hughes (1905–c1990), in her unpublished recollections, as 'a lovely country place', and this was confirmed by other residents. [16] Cows were to be seen, fruit trees were ubiquitous, and natural bush extended down to the harbour, where children loved to catch prawns. Many of the larger houses had tennis courts, which added to the spaciousness of the suburb; and as Myee Alvarez (1896–1988) emphasised in her unpublished memoirs, 'there were absolutely no cars'. [17] All the residents of her generation confirmed that the greatest changes they had seen in Hunters Hill were due to successive subdivisions and the increasing presence of the motor car. Until the 1950s, Hunters Hill remained a semi-rural back-water, in spite of the considerable presence of maritime industry at Woolwich.

Change, development and resistance

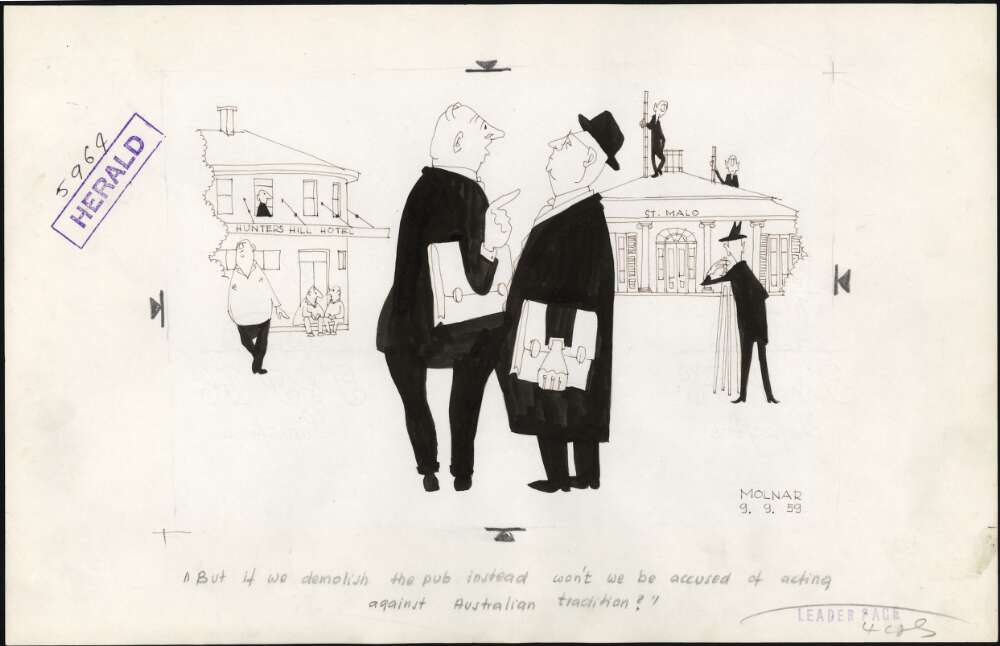

The years 1900–1960 saw successive low-density residential development, the growth and eventual decline of the waterside industries, and the sad neglect of many nineteenth-century buildings. Indeed the state government sanctioned the demolition of historic buildings when an expressway was built over the Lane Cove and Parramatta rivers in the early 1960s, cutting through the suburb. [media]Much lamented was the loss of Didier Joubert's gracious residence St Malo (c1856), demolished in 1961.

By this time, post-World War II development had begun in earnest. In 1959 the local Town Clerk, Roy Stuckey, reported 'tremendous development' and noted that great interest in Hunters Hill was being shown by 'people desiring to develop high density housing.' [18] Strata title was introduced into Sydney in 1961, which resulted in a proliferation of high-rise apartment blocks in many suburbs, and this was set to happen in Hunters Hill. Today the suburb would be studded with high-rise dwellings but for a remarkable grass-roots movement which began in the 1960s. [19] On 7 February 1968, over 500 residents, irate at the demolition of historic buildings and at the prospect of high density development, met at the Hunters Hill Town Hall. Following the example of the National Trust, they established the Hunters Hill Trust and put up a full board of candidates for the municipal elections in December 1968, the first time a civic trust had done this in Australia. All their candidates were elected. This turned the tide, arresting the demolition of historic buildings and halting the indiscriminate spread of home units.

Since the 1960s, Hunters Hill has been in the vanguard of the Australian conservation movement, and several leading environmentalists have lived there, including Vincent Serventy (1916–2007), Douglass Baglin, Philip Jenkyn and the remarkable 'Battlers for Kelly's Bush.' The Battlers were 13 local women who banded together to save eight hectares (20 acres) of bushland by the harbour. The land had been a buffer zone on TH Kelly's Sydney Smelting Company land, and when the smelting works closed in 1967 a developer, AV Jennings, took out an option to purchase the site and construct apartments, including three eight-storey blocks. The Battlers enlisted the support of Jack Mundey and the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation, who placed the world's first Green Ban on Kelly's Bush in 1971. In the same year, an oil company, Amoco, attempted to purchase The Garibaldi, demolish it, and build a service station. Again, the people of Hunters Hill rose up, defending this well-loved landmark, until the New South Wales government placed a conservation order on it in 1979. In 1981 the Register of the National Estate classified Hunters Hill as a Conservation Area for its importance as

an exceptional low-density garden suburb, which includes many historic buildings and structures. [20]

It was not until 1983, however, that the Battlers for Kelly's Bush finally won their long struggle. The New South Wales government bought the bushland from AV Jennings and made it a permanent public reserve under the care of the Hunters Hill Council. On 3 September 1983, the Premier, Neville Wran, declared, 'This piece of foreshore land has changed the whole face of conservation in Australia'. [21] The Hunters Hill Council's commitment to preserving historic Hunters Hill – both its natural and built environment – was borne out in a major heritage study commissioned by the council, undertaken by Meredith Walker and Associates, and published in 1984.

Campaigns for preservation

In the later twentieth century, numerous battles continued to be fought. Particularly fierce was the campaign waged by CRUSHH (Concerned Residents Under Siege in Hunters Hill) to prevent high-rise development at Pulpit Point on the Parramatta River foreshore, after Mobil Oil sold their storage depot there in 1988. After a number of years, a compromise was reached and, while there is no high-rise, the contrived grandeur of the Pulpit Point Estate is regarded as somewhat out of place in Hunters Hill. In 1984 the National Trust purchased the 1871 cottage at 38 Alexandra Street, originally called Carrum Carrum and now known as Vienna, conserved it and opened it to the public in Australia's bicentennial year 1988. Also as a bicentennial project, the council commissioned Beverley Sherry to write a history, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, with photographs by Douglass Baglin (published 1989).

The latest achievement of the twentieth century was the victory of a local group formed in 1997, calling themselves 'Foreshore 2000 Woolwich'. In 1997 the Commonwealth Department of Defence decided to sell off to the private sector substantial parts of its holdings around Sydney Harbour. There was a concerted battle by local community groups who joined in a coalition, called 'Defenders of Sydney Harbour Foreshores', to keep these lands in public ownership. Finally, in 2001 victory was achieved. [media]The government established a commonwealth trust to preserve the Defence Department lands, including those at Woolwich, for future generations.

In the first years of the twenty-first century, local residents worked with the council on two campaigns. When Hunters Hill was under threat of amalgamation with the municipality of Ryde in 2003, residents and the council united in vigorous protest, and won an unqualified victory. In 2007 local residents, again working with the council, succeeded in preserving a property of unique historic significance, The Priory. Formerly the Marist Fathers' mission house at the head of Tarban Creek, The Priory had for many years in the twentieth century been part of a public hospital, and in 2006 the State government intended to sell it off to private interests. Through a campaign waged by Hunters Hill resident groups and the council, it was transferred from the New South Wales Health Department to the New South Wales Department of Lands, to become part of the adjoining Crown reserve. It is now under the care, control, and management of the Hunters Hill Council, to be used as a multi-purpose cultural facility. By 2008 the council had identified over 1,200 elements in the municipality – including, for example, all stone walls – as contributing to Hunters Hill's heritage.

Hunters Hill's uniqueness

Hunters Hill comes into sharper focus when seen, within an Australian perspective, in relation to other early suburbs. It is markedly different from the closely developed terrace-house suburbs of the Victorian era, such as Sydney's Paddington and Glebe and Melbourne's Carlton. It has outlasted, in its essential character, a number of other early suburbs which also began as detached housing but which today retain only vestiges of their first selves, such as Hobart's New Town, Sydney's Woolloomooloo, and Brisbane's Kangaroo Point. It differs too from the suburbs developed around 1900 which grew out of the garden suburb movement inspired by Ebenezer Howard. The Sydney suburb of Haberfield and the Appian Way in Burwood, for example, were, like Hunters Hill, expressions of the Australian suburban ideal, but Hunters Hill predates them by at least 60 years. Although not comprehensively planned like the model garden suburbs, it evolved from the 1840s as 'a very thorough example of a garden suburb.' [22] [media]There have been waves of subdivision, especially after World War II, and there is ongoing tension between conservation and development, yet much of the sandstone fabric of the historic built environment remains and the pattern of detached houses in gardens has survived. This is remarkable for a place less than five kilometres from the city centre. In the 1920s Maybanke Anderson, a pioneering feminist who lived in Hunters Hill, described the suburb as a kind of Arcadian retreat, and in 2008 it was still being described, by another resident, the actor Cate Blanchett, as 'a sanctuary within the city.' [23]

References

Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989

Meredith Walker and Associates, Hunter's Hill Heritage Study, Hunters Hill Council, Hunters Hill, 1984

Notes

[1] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 20–21

[2] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, p 22

[3] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, p 25, also pp 22–26

[4] Val Attenbrow, Research into the Aboriginal Occupation of the Hunter's Hill Municipality, Hunter's Hill Municipal Council, 1988

[5] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 31–32

[6] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 28–30

[7] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 39–58

[8] Sydney Morning Herald, 2 January 1858

[9] Australian Men of Mark, Maxwell, Sydney, 1888, vol 2, p 197

[10] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 48–50, note 24

[11] Meredith Walker and Associates, Hunter's Hill Heritage Study, Hunters Hill Council, Hunters Hill, 1984, pp 19, 21 and figs 18–20

[12] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 63–66

[13] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, p 93, also pp 87–88, 93–96

[14] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 71–74, 78–79, 113–17

[15] Beverley Sherry, 'Hunters Hill' in Peter Pierce (ed), The Oxford Literary Guide to Australia, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 1987, pp 81–83

[16] Doris Hughes, 'The History of Woolwich', unpublished manuscript, Hunters Hill Historical Society Archives, 1987, p 4; Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 85–93

[17] Myee Alvarez (née Cureton), 'Reminiscences of Life in Hunter's Hill 60 years Ago', unpublished manuscript, Hunters Hill Historical Society Archives, 1975, p 2

[18] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 96–97

[19] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 96, 97

[20] Australian Heritage Commission, The Heritage of Australia: The Illustrated Register of the National Estate, Macmillan, South Melbourne, 1981, pp 2/28–2/29

[21] Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, p 105

[22] David Saunders, Australian Council of National Trusts, Historic Places of Australia, Cassell, Stanmore, NSW, 1978–79, vol 1, 'Hunter's Hill', p 293; Beverley Sherry, Hunter's Hill: Australia's Oldest Garden Suburb, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1989, pp 12–14, 108

[23] Maybanke Anderson, 'The Story of Hunter's Hill', Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, no 12, 1926, pp 141–66; The Sydney Magazine, no 65, September 2008, p 45

.