The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney in 1858

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney in 1858

By the mid-1850s, Sydney resembled a bustling English seaport. [media]Steamships ran between Europe and Australia, and mail arrived in 135 days rather than the 275 days it had taken in the early nineteenth century. Sydney had adopted a tone of Victorian sobriety, and spending time in Sydney was in no sense roughing it. Sydney's residents had museums and zoos to visit, and on Sundays horse-drawn omnibuses and ferries took them on trips to the 'countryside', to Botany, the Cooks River, down the Parramatta River, to Manly, or to Watsons Bay. Promenading in late summer afternoons down Lovers Walk in Hyde Park was also popular. The walk ran from St James Church to Liverpool Street. People enjoyed strolling in the park, with the pleasant sea breezes and views down to the boats and villas on the harbour. [1] [media]Gas lamps illuminated the streets of Sydney at night.

The spectacle of entering the harbour and seeing Sydney for the first time was often commented upon, as it was by John Askew, visiting in 1857:

Tiers of fine buildings seem to rise one above the other, like the seats in an amphitheatre, and towering above them all, is the tall spire of St James' Church. [2]

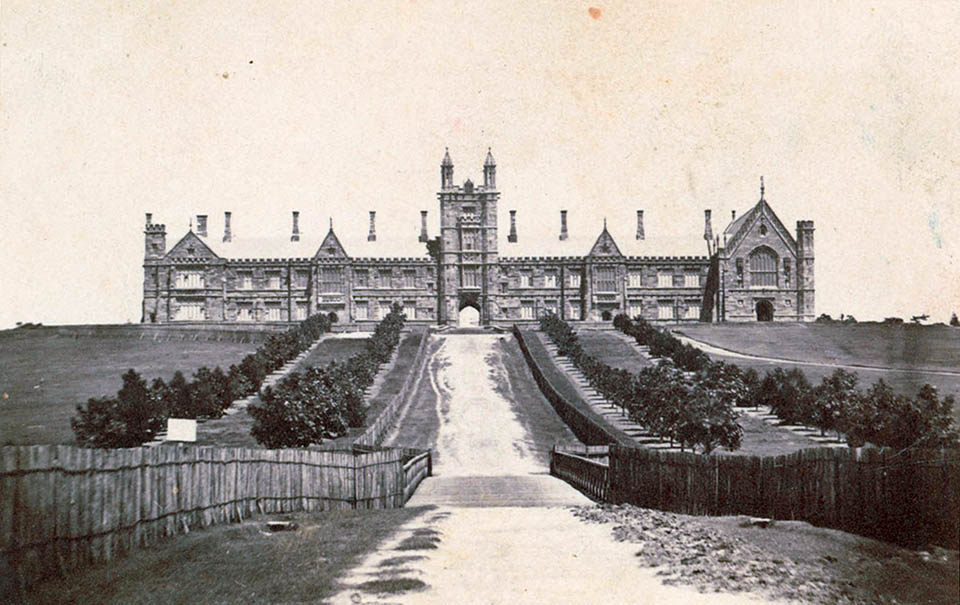

The growing maturity of Sydney as a colonial city was indicated by the establishment of the University of Sydney, in 1852. The university boasted the motto Sidere mens eadem mutato which means 'the same minds under different stars'. The implication of this motto was that the only differences between the new colonial society and that of Britain were geographic, and not cultural. The architecture of the original buildings of the university reflects this notion of entire transplantation. [media]The Edmund Blacket-designed main buildings and St Paul's College were constructed between 1854 and 1860 in the Gothic Revival style, with little regard to difference in climate.

[media]The main commercial streets in the city were (and still are) George and Pitt streets. In the 1850s, when Pitt Street was extended to Bridge Street, the Tank Stream was covered completely. The finest shops were in Pitt Street between King and Market streets. There was still, however, a motley mix of single-storey and multi-storied buildings. The northern end of the city (north of the General Post Office) was evolving into the financial centre. The opening of the Royal Exchange in 1853, on the corner of Gresham, Pitt and Bridge streets, promoted this, as did the construction of solemn banks built in the various revivalist architectural styles of the Victorian era.

In George Street, the 'bucks and Brummels of the Colony' visited the Café Francaise. As well as good food, there were chess and billiard clubs there. Lunch time was taken seriously – the church bells would ring in the city at one o'clock each weekday afternoon, heralding the lunch hour. For one patron of the Café:

Little marble tables, files of Punch and the Times, dominoes, sherry cobblers, strawberry ices, an entertaining hostess and a big, bloused, lubberly, inoffensive host, are the noticeable points of the Café left on my recollection. They serve eight hundred dinners a day at this house. [3]

As the city's commercial activity grew, the two main commercial east-west streets, Hunter and King streets, became the home of unusual and specialist shops and small businesses.

[media]The finest town houses were in Macquarie Street. They were often grand and up to four storeys high. Askew described the scene lyrically in 1857:

The best time to see this neighbourhood in all its glory is on a summer's evening, about an hour after sunset, when the drawing rooms are in a blaze of light. Then the rich tones of the piano or some other musical instrument are heard gushing forth from the open windows, accompanied by the sweet melody of female voices … Beautiful ladies, dressed in white may be seen sitting upon the verandahs, or lounging on magnificent couches, partially concealed by the folds of rich crimson curtains in drawing rooms which display all the luxurious comforts and magnificence of the East, intermingled with the elegant utilities of the West. [4]

[media]Another new residential area in the town was Wynyard Square, recently vacated by the army when it moved to Victoria Barracks at Paddington in 1848. Some of the residents of the area around Wynyard Square were Jewish merchants who lived in smart town houses.

In 1858, Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide were linked by telegraph. The same year, an enthusiastic social observer, WS Jevons, engaged in a survey of Sydney housing. He noted that successful merchants, shopkeepers and professional men lived in mansions or villas, usually on elevated land just outside the city, such as in Glenmore Road, Paddington, or Darlinghurst, Elizabeth Bay or Glebe, or in the middle of town in Macquarie Street or in Lower Fort Street. The middle classes, by which he meant skilled workers, lived in four- to five-roomed houses, clustered in districts such as Surry Hills, Strawberry Hill, Redfern, Glebe, Pyrmont, Balmain and the higher area of the Rocks around Millers Point.[media] The worst housing was much older, and located at the Rocks, the lower end of Sussex Street and around Druitt and Goulburn Streets. Jevons was full of moral indignation about the state of the residents:

I am acquainted with most of the notorious parts of London … but in none of these places perhaps, would lower forms of vice and misery be seen than Sydney can produce. Nowhere too is there a more complete abandonment of all the requirements of health and decency than in a few parts of Sydney. [5]

Notes

[1] John Askew, A voyage to Australia and New Zealand, Simpkin Marshall, London, 1857, quoted in Frank Crowley, A Documentary History of Australia, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1973–1980, vol 2, p 315

[2] John Askew, A voyage to Australia & New Zealand, Simpkin Marshall, London, 1857, quoted in Frank Crowley, A Documentary History of Australia, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1973–1980, vol 2, p 185

[3] F Fowler, Southern Lights and Shadows, Sampson Low, London, 1859; Barry Groom and Warwick Wickman, Sydney, the 1850s: The lost collection, Macleay Museum, University of Sydney, Sydney, 1982, p 13

[4] John Askew, A voyage to Australia & New Zealand, Simpkin Marshall, London, 1857, quoted in Frank Crowley, A Documentary History of Australia, Thomas Nelson, Melbourne, 1973–1980, vol 2, p 202

[5] WS Jevons, quoted in Lucy Turnbull, Sydney: Biography of a City, Random House, Sydney, 1999, p 107