The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Sydney rock oysters

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Sydney rock oysters

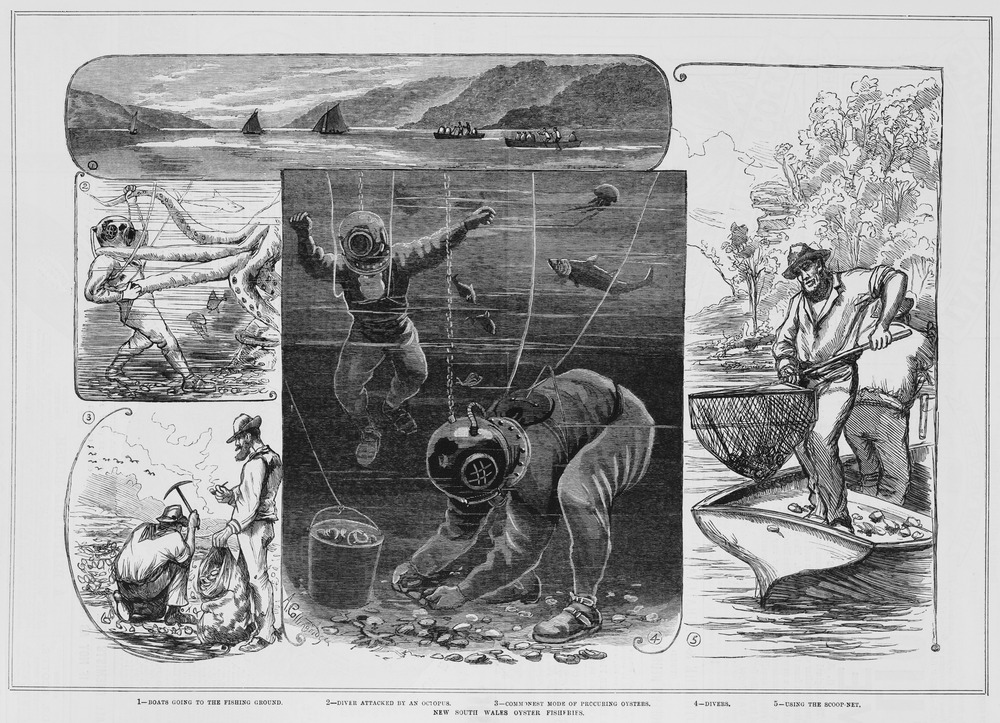

[media]Oysters have been food for elites, as well as for the coastal communities who collected them, for thousands of years. They can be found on any seashore or estuarine area with the right climatic conditions. Sydney's Eora, Dharug, Tharawal and Gweagal peoples were certainly eating them in large numbers for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. Shell deposits in Sydney middens have been carbon-dated to around 6000 BC.

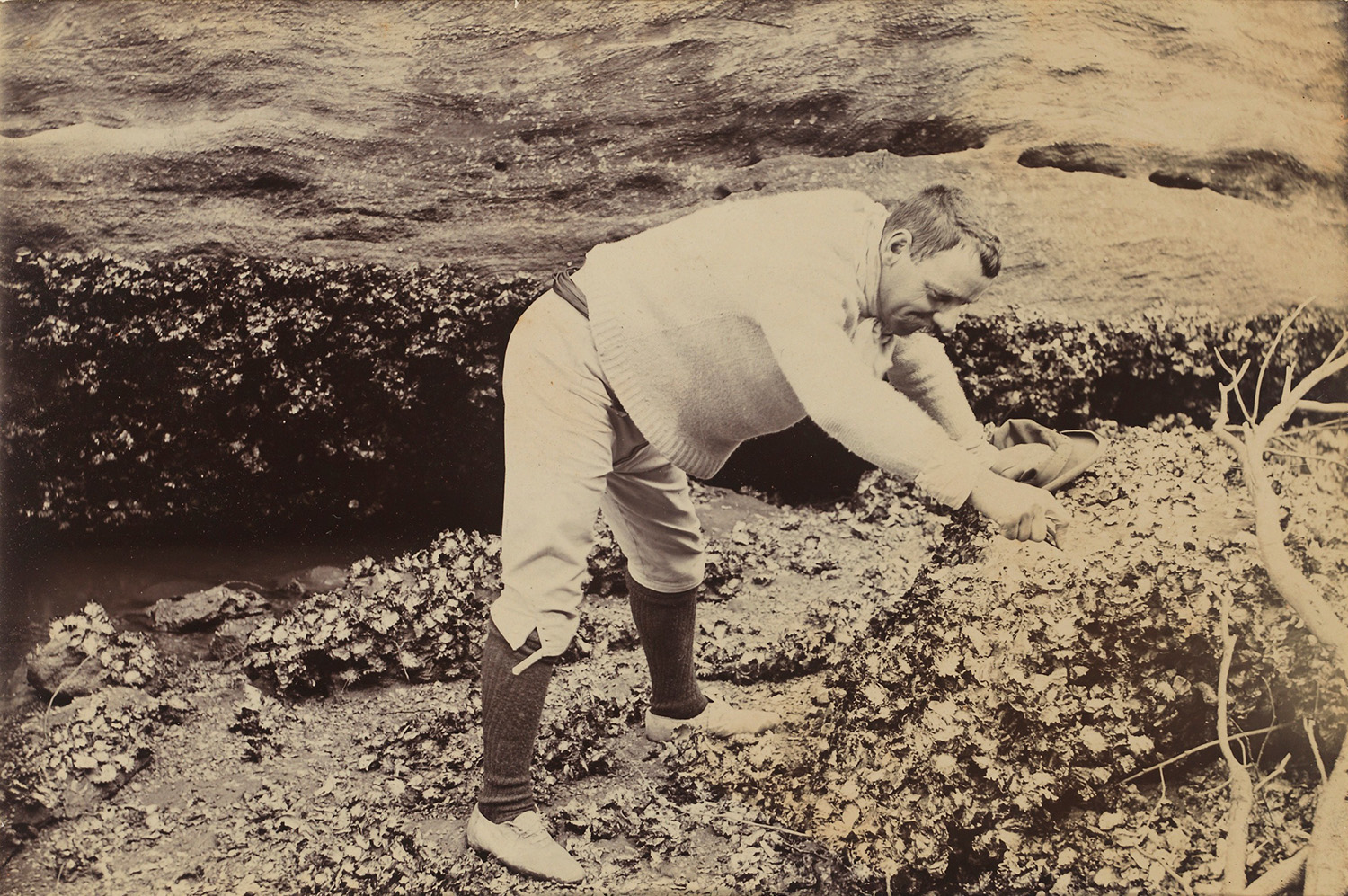

[media]Sydney rock oysters are bivalve molluscs which begin life as veliger larvae. These form just hours after fertilisation of the eggs. The eggs and sperm are released into the water to fertilise. The veliger are microscopic, free-swimming and look for a place to settle. By two or three weeks they attach themselves to a hard surface, such as spat collecting sticks, and are now called 'spat'. They do not yet have hard shells, for this is a characteristic of mature oysters.

Sydney rock oysters are not to be confused with Pacific oysters which are their larger, less succulent, far more rubbery cousins. The Sydney oyster is smaller, softer and has a more distinctive taste. It takes about three years to reach maturity, while the Pacific takes 12 to 18 months.[media]

Oyster farming

[media]Sydney lies in the centre of some of the best oyster-producing regions in the world, from Port Hacking and the Georges River to Broken Bay. The commercial cultivation of Sydney rock oysters began only in 1872. Early European settlers had taken to the local product with gusto, but they also burned the shells to produce lime for mortar. This depleted the natural population, so the government banned the burning of oysters for lime, leading to deliberate farming.[media]

[media]The first type of oyster farming was the French method, using canals. This was unsuccessful because the canals soon silted up and there was high heat kill in summer. In 1888 a severe infestation of shell-boring mud-worms, which thrive if oysters are partially silted, seriously affected the industry. This forced the development of intertidal farming techniques for catching and raising oysters. One method involved the use of materials such as stones and shells, known as cultch, placed on raised beds where the water flow was sufficient to enable the control of silting. A variation was to use stakes, cut from casuarina or mangrove trees, inserted vertically into the sediment. Stake cultivation has gradually developed into the modern stick and tray method.

[media]Today Sydney rock oystersstill account for 94 per cent of edible oyster production in New South Wales. Annual production, which was fairly stable in the last three years of the twentieth century, at around 7.9 million dozen a year, fell to 7.4 million dozen in 2001–02. Producing about eight million dozen oysters a year on average, New South Wales accounts for 60 per cent of Australia's oyster harvest. The value of production in 2001–02 was $29.6 million at the farm gate. State production peaked at about 14.5 million dozen in the 1970s, with declining output linked to poorer water quality. In the 1990s the aggressive QX disease decimated the Georges River oyster industry.

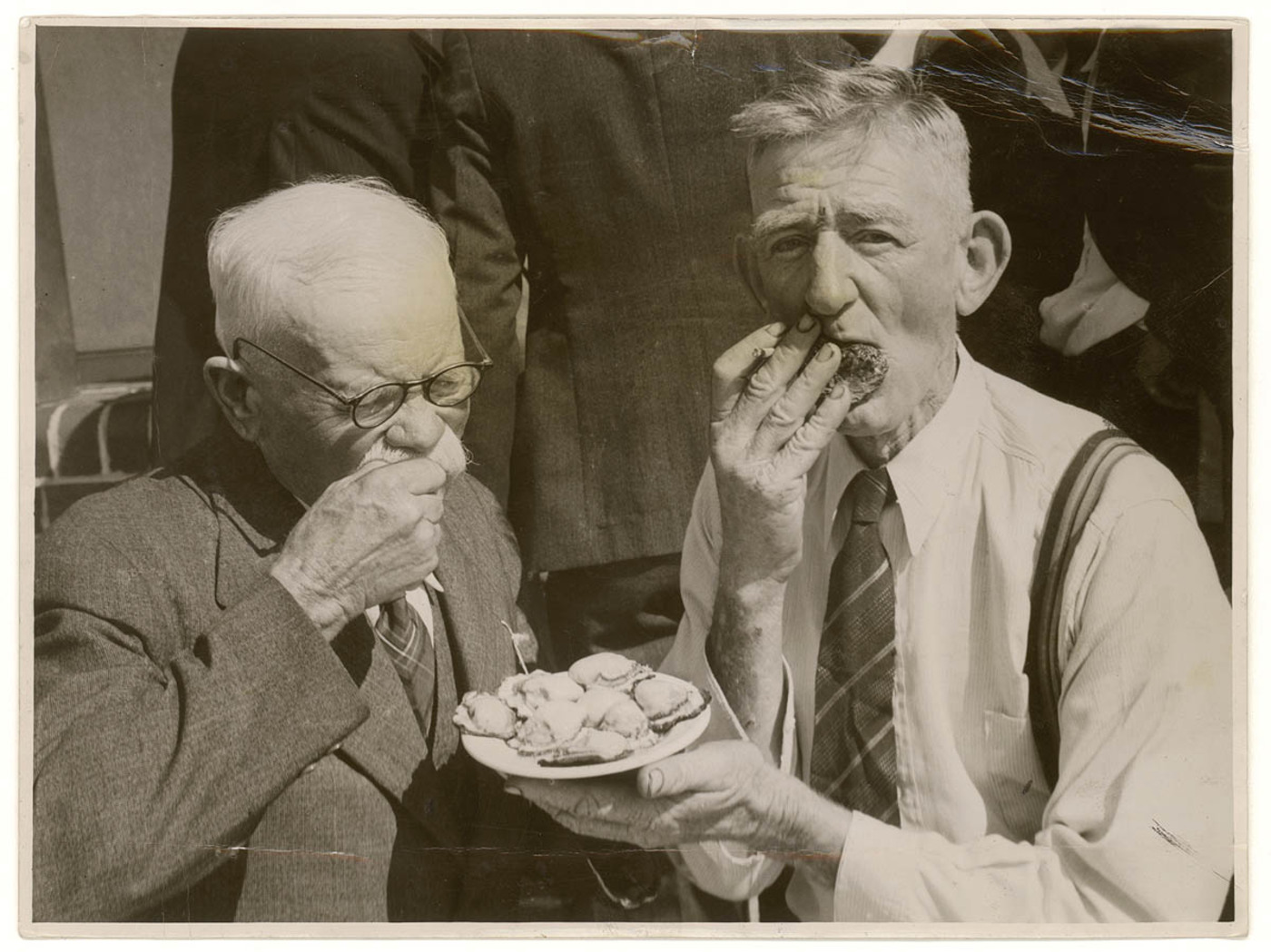

Oyster eating

Oysters have long held an association with sensuality. At a dinner at the Hotel Australia in Sydney, the editor of the Sydney Morning Herald noted to Sir Henry Parkes that 'these oysters are good'. Parkes is said to have replied,

I don't need these adventitious aids. Lady Parkes and I until quite recently have been in the habit of having connection 17 or 18 times every night, and we now have connection 10 or 11 times. [1]

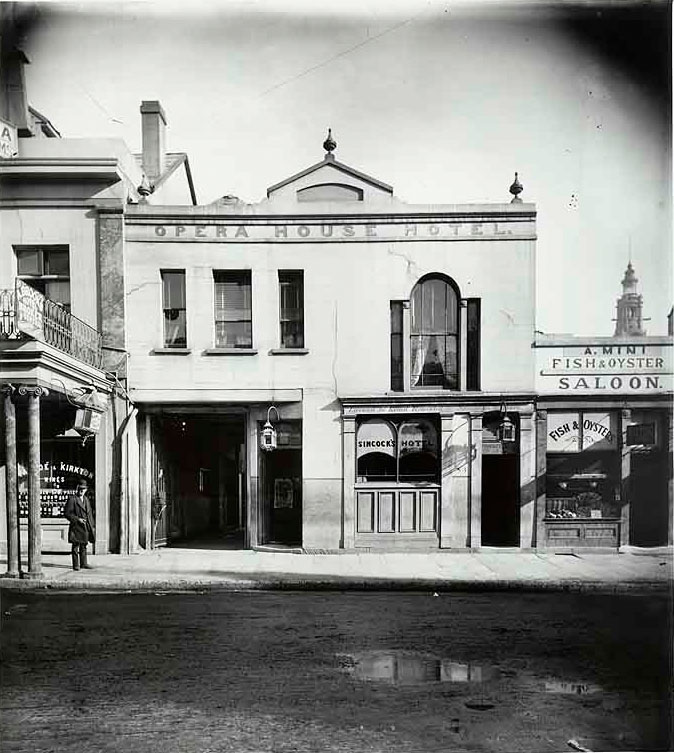

[media]Indeed, the city's history is alive with references to the oyster and its culture – from the suburb named Oyster Bay to the popularity of oyster bars, which by the late nineteenth century were common in Sydney and often run by southern European migrants.

During the twentieth century, tastes in eating changed and for a while, oysters went out of fashion. Oyster bars began to disappear and fish and chip shops began to replace them. Today, oyster bars have made a comeback, and Sydney rock oysters are back on the menu at many chic restaurants.

Perhaps the most unusual of the current crop of oyster bars is the Sydney Cove Oyster Bar, on the eastern shore of Sydney Cove. The Federation building which houses it dates back to 1908 when it was known for its 'workers' facilities', and later used as a public lavatory. It remained in use until 1987 when Circular Quay was redeveloped in preparation for Australia's bicentennial celebrations.

[media]Oysters can embellish a dish or be eaten on their own. Connoisseurs love them with just a squeeze of lemon juice, and a hint of ground black pepper. In 2004, the Sydney Morning Herald Good Food Guide noted that 'the little Sydney rock is loved for its unique flavour and long shelf life'. Indeed, what would a Sydney summer be without a plate of oysters, followed by prawns and a beer or two?

Notes

[1] ‘At a dinner given by Major Z.C. Rennie at the Hotel Australia, Editor Curnow, of Sydney Morning Herald, remarked 'These oysters are good.' Parkes: 'Mr Curnow, I don't need these adventitious aids. Lady Parkes and I until quite recently have been in the habit of having connection 17 or 18 times every night, and we now have connection 10 or 11 times.' Curnow was very quiet for the rest of the dinner (this was said out loud before all the table); but Parkes later, proposing or replying to the toast of 'Federated Australasia' made a splendid speech, full of elevated thought and moving language.’ As told by PJ Holdsworth to AG Stephen, from Stephens’ Bulletin Diary. In Colonial Voices: Letter, Diaries, Journalism and Other Accounts of Nineteenth-Century Australia, edited by Elizabeth Webby, (University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Qld 1989), p 355, http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:200515 viewed 13 June 2016

.