The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

The School of Arts movement

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

The School of Arts movement

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, about 140 schools of arts or mechanics' institutes were established in Sydney, sometimes also known as literary, railway or workingmen's institutes. In many inner-city and interwar suburbs the buildings remain, prominently located on the main street or near the train station. Most have now been taken over by local councils, or the properties sold to private interests. But they were originally established by volunteers as independent community organisations, assisted by a small government subsidy, and they thrived as centres of local community life. Today, their legacy in Sydney is more than just the surviving buildings. Out of these humble voluntary operations developed the local public library, the modern community or neighbourhood centre, and formal systems of adult and technical education. [1]

Origins of the movement

The school of arts movement, also known as the mechanics' institute movement, spread through the English-speaking world in the mid-nineteenth century. The Enlightenment had engendered a passion for science, rationality and popular improvement. Public lectures were an increasingly common mode of social intercourse in the United Kingdom, and the principle vehicle for both political reform movements and attempts at the general diffusion of scientific knowledge. Meanwhile, the industrial revolution was changing both the nature of work and the skills and knowledge required of manual workers, known in those days as mechanics or artisans. [2]

Underpinning the movement were the ideas that industry and society would benefit from a scientifically educated artisan class and that a new breed of inventors would arise from this class. [3] One advocate of mechanics' institutes explained the reasoning:

The steam engine is the discovery of one who laboured as a mechanic; and we urge, give men of this class science – do not leave them to the crumbs which fall from the rich man's store, but let all that can, be imparted, and the steam engine is only the dawn of what will be achieved. [4]

There was also the belief that working men would be convinced of the benefits of technology and of the laws of classical political economics, and that disorderly behaviour would be counteracted by the wholesome experience of attending lectures and classes. [5] Mechanics' institutes were

the machinery of intellectual and moral improvement... Wherever the opportunities of instructive pleasure are afforded, they are readily seized, and criminal indulgences become... odious. [6]

The movement originated in Scotland. Natural philosopher George Birkbeck at the Andersonian Institute in Glasgow set the example in 1800. Responding to interest shown by a group of Glasgow working men in one of his centrifugal pumps, Birkbeck ran a series of Saturday evening lectures on 'The mechanical properties of solid and fluid bodies'. The lectures were popular: 75 mechanics attended the first lecture; the number rose to 500 over the following weeks. As historian Alex Tyrrell points out, 'Glasgow was an industrial centre and pumps were essential parts of the transition to steam power.' [7]

Following Birkbeck's example, Leonard Horner, an upper-middle class Presbyterian businessman and geologist, founded the first School of Arts in Edinburgh in 1821. [8] In the annual report of 1827, one of the directors described the School as part of 'that magnificent plan … which has for its object the universal diffusion of useful knowledge among the lower orders.' [9] Another director claimed such a school offered everything a working man might need to attain upward mobility:

By such institutions, any artisan possessing superior talents [is] furnished with the means requisite for their development; he [has] opened to him the road to the highest distinction which might be attained by any individual… No plan was ever devised better calculated to promote this object than that which [has] been adopted in the School of Arts for the education of Mechanics. [10]

The full name of that first institution was 'The School of Arts of Edinburgh for the Instruction of Mechanics in such branches of physical science as are of practical application in their several trades'.

In the following years, similar institutions proliferated across the Empire. One historian suggests that the 'mechanics' institute movement may well have been one of the most successful examples of British educational imperialism'. [11] Within a decade there were schools of arts or mechanics' institutes in London, Manchester, Montreal, as well as in New York, Boston and Philadelphia. By 1850 there were over 700 in Britain alone. [12] They later spread to the West Indies, South Africa, India and the Pacific. [13] Australia was well and truly part of this picture: 'As far as Australia was concerned', observes Tyrell, 'there was no 'tyranny of distance'. The Hobart Mechanics' Institute was founded as early as 1827 and Sydney followed in 1833.' [14] Indeed, as Philip Candy notes, the 'institute movement in Australia was more widespread and arguably more influential at a population level, than in any other part of the British Empire.' [15] According to early indications of research currently underway by Elisabeth Richardson, over the course of about a century, around 750 schools of arts or mechanics' institutes were established in New South Wales alone; some 140 of these were in Sydney and suburbs. [16]

A makeshift mechanics' institute at sea

A group of Scots on a sea voyage to Australia in 1831 were the ones who physically transferred the mechanics' institute concept to Sydney. The Stirling Castle had been chartered to sail to Sydney from Greenock in Scotland, by Reverend Dr John Dunmore Lang who wanted to build his new Australian College, but couldn't find local tradesmen with adequate skills to build it, nor teachers to staff it. So with financing from the colonial government, Lang brought out from Scotland about 50 'mechanics' – stonemasons, carpenters, blacksmiths – with their families. He also imported five clergymen to teach at the College, one of [media]whom, Reverend Dr Henry Carmichael, volunteered to be 'the schoolmaster of the ship' during the five-month voyage. [17] Vernon Crew comments that 'These shipboard classes were among the earliest, as they were certainly among the most unusual of Australian adult education classes.' [18] They formed a direct link between the world's first mechanics' institute in Edinburgh and Sydney's first like institute, as Carmichael recorded:

One of [the mechanics on board] happened to have a copy of the elements of Algebra and Geometry by Mr Lees, of the Edinburgh School of Arts, and another a copy of Ingram's small Treatise on Arithmetic. These works, hence, became our textbooks. The class met [five days per week]... and was seldom interrupted during the whole of the voyage... [Later] a proposal was made to form another class, to meet twice a week for the purpose of discussing ... the Principles of Political Economy. This proposal was met with eagerness; and a class of thirty ... immediately enrolled themselves... With these studies, the expediency and benefits were discussed of forming themselves into an association which should combine the advantages of a Mechanics' Institution and a Benefit Society, and a skeleton of such a society was accordingly drawn up, with the intention on the part of the mechanics, of bringing its plan into operation... after their arrival in New South Wales. [19]

Fertile ground

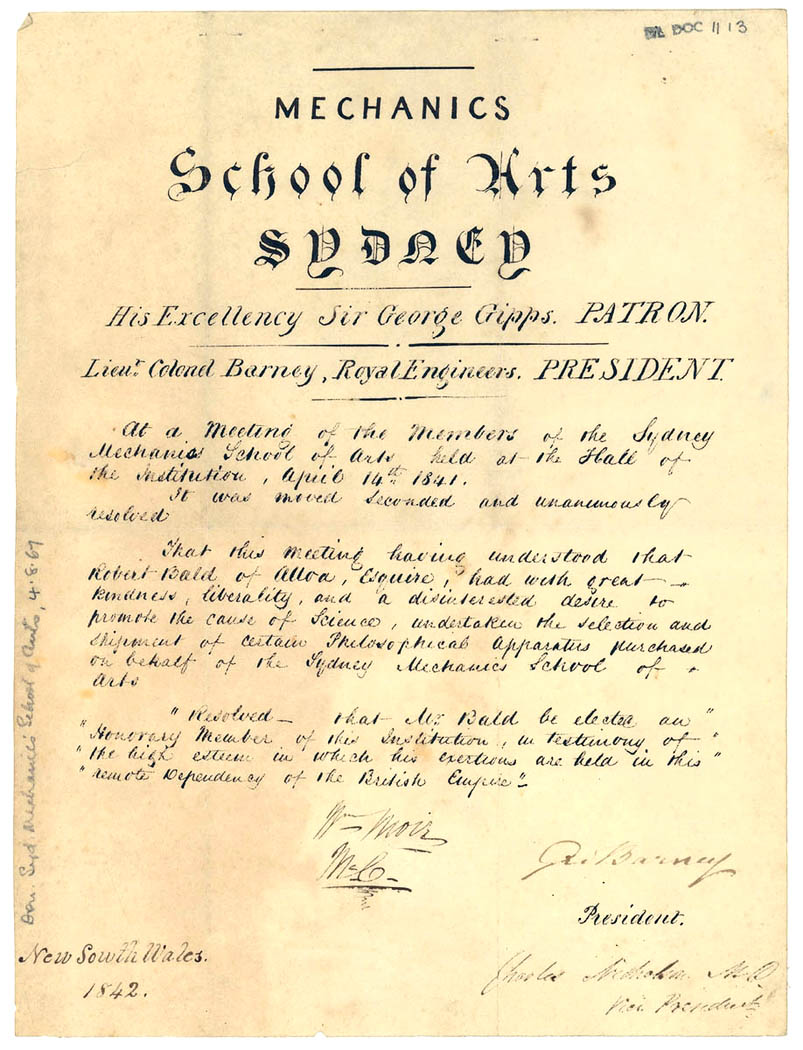

[media]In March 1833, some 18 months after the arrival of the Stirling Castle, the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts was established, with Governor Richard Bourke as patron, the Surveyor-General Major Thomas Mitchell as President, and Carmichael as Vice President. The stated purpose of the institution was 'the diffusion of Scientific and other useful knowledge as extensively as possible throughout the Colony.' [20] The intended means for achieving this objective were published in the newspaper: the establishment of a library containing books of scientific and useful knowledge for the use of members; the delivery of lectures upon the various branches of science and art; the formation of classes for mutual instruction; and the purchase of apparatus and models for illustrating the principles of physical and mechanical philosophy. [21]

The School proved popular in the 1830s. Two hundred and fifty lectures were given in the first 10 years on subjects ranging from chemistry, electricity and steam, to how to choose a horse, phrenology and vulgarities in conversation. Membership increased from 91 in 1833 to 609 by 1838. Through Governor Bourke's influence, an annual subsidy from the Legislative Council was granted. In 1836 the School moved to its own purpose-built home at 275 Pitt Street, where it remained for the next 150 years. [22]

The advent of Sydney's first mechanics' institute was not the first self-improvement initiative in the colony. Elizabeth Webby has shown that several short-lived libraries and societies dedicated to self-education sprang up in and around Sydney from about the early 1820s. The Philosophical Society of Australia (1821–2), the Reading Society (1822–4) and Robert Campbell's Australian Circulating Library (1825) are examples. [23] These attempts were no doubt motivated by the kind of frustration expressed by young lawyer George Allen writing to his brother in England from Sydney in 1820:

…this place is not like London for amusements, here we have neither society nor places of amusement, there is not [sic] library here to spend a few hours in; my only employment after the business of the day is to retire to my own room ... and read my books of which I am sorry to say I have but a slender stock. [24]

[media]The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts differed from these earlier libraries, clubs and societies in two important ways. First, it was destined to endure – indeed, it still exists today – and second, it had not the local elite, but rather the colony's working class, in its sights.

By the turn of the century there were about 40 schools of arts or mechanics' institutes in Sydney and suburbs. [25] As Vice-President of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, Reverend Dr John Woolley had said in 1860:

Our mother-school has sent forth colonies into every suburb; and the example has long since been followed in every provincial town and populous neighbourhood. [26]

Top-down or bottom-up?

According to Carmichael, in spite of their enthusiasm during the voyage, the Stirling Castle mechanics alone were not up to the task of founding the institution once they arrived in Sydney:

Amidst the difficulties of a first settlement... the scheme sketched on board for their [the mechanics'] guidance on shore was not followed up. One or two meetings... were held... but nothing was done effectually among the mechanics themselves; and it seemed evident that the project would fall entirely to the ground, unless taken up and prosecuted, at least to a certain extent, by others than the parties more immediately interested. [27]

Those 'others' were, in the first instance, Governor Bourke and Henry Carmichael.

Vernon Crew shows that the Stirling Castle mechanics were involved in the early activities of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts. At least 11 attended the preliminary meetings called by Carmichael, and several became members of the management committee: according to the rules of the School of Arts, 13 of the 20-strong committee had to be mechanics; on the first committee, more than half of these were Stirling Castle mechanics. Many of the Stirling Castle mechanics settled in Millers Point on Clyde Street, which thereafter became known colloquially as 'Scotch Row'. [28] Many also joined as ordinary members in the first year. [29]

But within a few years, the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts was struggling to retain the membership and involvement of manual workers. Its 1837 annual report lamented the absence of mechanics and their 'apparent indifference to their own improvement as well as to the benefits which accrue to their posterity from the full establishment of so philanthropic an institution.' [30] As the 1830s progressed, the School's members were increasingly middle-class professional men: merchants, shopkeepers, clerks and office workers. [31]

[media]This pattern of middle-class patronage tended to repeat itself in the later institutes that emerged in Sydney. In analysing the contradiction between the stated aims of schools of arts and their apparently middle-class composition, Derek Whitelock concluded that the institutes tended to serve the interests and shore up the power of the local elite. [32] But Roger Morris questions this conclusion. He has made a study of five inner-city institutes, established between 1865 and 1907: Balmain, Glebe, Newtown, Leichhardt and Rozelle. These five were originally called Workingmen's Institutes but all except Balmain later changed their names to either School of Arts or Mechanics' Institute. He writes:

While it would be patently untrue to claim that these Institutes arose as a direct product of militant and unalloyed proletarian consciousness, it would be equally untrue to claim that they were merely the creation of middle class paternalism. The situation, both in political and educational terms, was much more complex... [33]

Morris argues that these inner-city institutes did serve the interests of working-class members, meeting 'at least to some extent, their needs for recreation, companionship and intellectual stimulation.' He points out that Labor Electoral Leagues and unions used their facilities for meetings, and their libraries stocked contemporary socialist works (alongside a great deal of popular fiction); their debating clubs explored left-wing topics like Land Nationalisation and the Advantages of Cooperation, while their lecture programs featured speakers like Tom Mann and helped popularise progressive ideas. [34]

Importantly however, Morris shows that the members of these inner-city institutes were from a particular component of the working class – namely, the non-conformist Protestant working class, whose characteristics he goes on to describe:

They had a strong tradition of self-education and mutual self-improvement through involvement in cooperative and fraternal organisations... Many Protestant working people, as well as being resolute trade union members and loyal labour voters, were also orderly, respectable, home-owning and chapel-going. Some were, in addition, anti-gambling and strong supporters of the temperance movement. [35]

In many respects then, these working people had much in common with the Protestant middle class, who had spearheaded the school of arts movement, and whose interests were ultimately so well served by such institutes.

Elisabeth Richardson's survey-in-progress of schools of arts and mechanics' institutes in New South Wales shows that in the case of Sydney, schools of arts were far more numerous in working-class suburbs. There were none in the more affluent areas of Hunters Hill and Mosman, and only one in Woollahra, Lane Cove, Strathfield, Manly and Burwood. Furthermore, they tended to proliferate in the Protestant areas of Sydney and were much less common in suburbs dominated by Roman Catholics. [36] By way of explanation, Richardson (like Morris) points to the Protestant tradition of support for education initiatives. She also notes that local clergymen commonly played a central role in the establishment of schools of arts. Then, as rare educated people, clergy were frequently called upon to act as lecturers. [37]

Two distinct varieties in Sydney

Roger Morris has identified two categories of schools of arts or mechanics' institutes in Sydney. Those belonging to the first category were established in the middle decades of the nineteenth century; they include the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts (1833), the Richmond School of Arts (1858), the Balmain Workingmen's Institute (1865) and the Granville School of Arts (1880), to mention just a few. These early institutes emphasised intellectual and educational goals for working people, and were modelled on Scottish and British antecedents. But because Sydney at this time was barely populated and minimally industrialised by comparison with the United Kingdom, they struggled to keep focussed on serious programs of scientific education for the labouring class. They found they had to diversify their offerings to remain viable. As Geoffrey Serle observed:

Within a few years of their foundation, the purely recreational element came to dominate, the classes dwindled away, and while the libraries remained useful… the halls became meeting places and dance and billiard rooms. [38]

[media]It was this diversification, this pragmatic attending to local community needs that characterised what Morris calls 'a distinct Australian model... an Australian School of Arts.' The model came into its own in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, as large parts of Sydney's population shifted from rented inner-city terraces to new owner-occupied detached houses in suburbs, spreading along the newly developed rail and tram lines. In almost all of these new suburbs, a school of arts or mechanics' institute was quickly established. These so called 'second-wave institutes' had modest goals, centred not so much on educating the artisan class, but rather providing a local home for reading, culture, civic action, recreation and entertainment. [39] Examples include the Kogarah School of Arts (1886), the Blacktown School of Arts (established as the Blacktown Mutual Improvement Association, 1905), the Oatley School of Arts (1905) and the Guildford Soldiers' Memorial School of Arts (established as the Guilford School of Arts in 1910). As Morris observes, these second-wave schools of arts

played an exceptionally important role in the development of ... Australian society and its local communities... [They] provided a social focus to... [life in] new suburbs: a focus sorely needed, given the almost complete absence of social infrastructure in these suburbs peopled by their newly home-owning lower middle-class and upper working-class populations. [40]

Failure or success?

As far back as 1851, historians of adult education were assessing the British schools of arts as failures according to their original aims: they had not educated the mechanic in the scientific principles underlying his trade, nor had they succeeded in promoting the mental and moral improvement of the working classes. [41] 'The survival of the English institutes', observes O'Farrell,

was directly related to the degree to which they abandoned their original purpose... By 1840, except in the larger Scottish institutes, the systematic science courses which had been the raison d'être of the early institutes gave way to a miscellaneous programme embracing popular science, literature, music, history, travel and phrenology. [42]

But what is interesting in Sydney is that for a few decades from about the mid-1860s, some of the early Sydney institutes did achieve the original purpose of technical education for working people. Indeed the entire New South Wales Technical and Further Education system grew directly out of the school of arts movement in Sydney.

As far as the other principle objective of school of arts movement, namely, the promotion of intellectual and moral improvement of the working classes, it is not difficult to argue that, during the movement's heyday, Sydneysiders of all classes benefited from the opportunities for rational recreation offered by the institutes as an alternative to pubs and sport.

Technical education

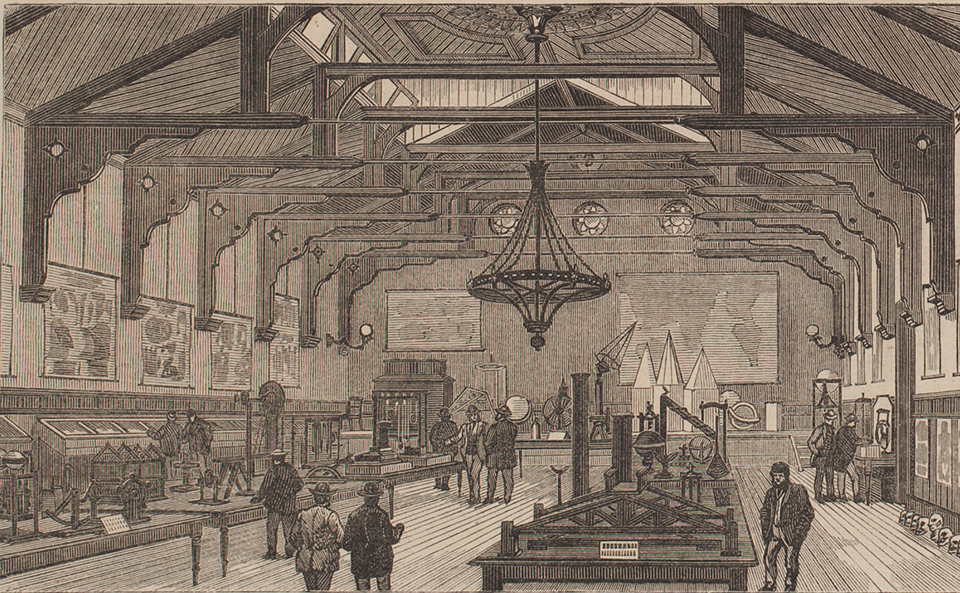

[media]Some have suggested that the reason the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts struggled to attract artisans to its lectures and classes after its establishment in 1833 is that Sydney was not yet industrialised enough for mechanics to need additional instruction. Vernon Crew writes:

Colonial society was certainly at a very early stage compared with that in Britain... In Carmichael's time the lectures were largely unrelated to the practical needs of mechanics. Even when the relationship between the scientific principles taught and the practical application to various trades and occupations could be seen there were few mechanics with sufficient education to benefit from the instruction. [43]

Even so, says Joan Beddoe, the social promise of the school of arts movement held enormous appeal in colonial society:

The transfer of the concept [of mechanics' institutes] to the Australian colonies created an intriguing scenario, for initially there was no industrialised society here. Rather, there was great demand for skilled labour for building purposes, and a very unequal society of convicts, emancipists and free immigrants. The concept of acquiring skills for the labourers was attractive enough, but the possibility that the movement could help stabilise society was irresistible. [44]

Moreover, as the nineteenth century progressed, industrialisation in Sydney quickened, and the need for technical education grew. When the engineer Norman Selfe started teaching a class in mechanical drawing at the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts in 1865, its popularity amongst tradesmen led to the introduction of other practical, vocational subjects. [45] In the 1870s the School of Arts committee started discussions with the newly established Engineering Association of New South Wales and the New South Wales Trades and Labour Council about the need for a separate technical college. Finally in 1878 the Technical and Working Men's College was established under the auspices of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts. It quickly became known as the Sydney Technical College, and was an immediate success. It soon outgrew the capacity of the School of Arts, which was merely a voluntary community-based organisation. [46] In 1883 the government came to the party, assuming financial responsibility and appointing a Board of Technical Education to run the College, many members of which were drawn from the School of Arts committee. The College became the centre of a rapidly expanding, government-run, formal system of technical education in New South Wales, later known as TAFE. [47]

The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts wasn't the only school of arts in Sydney to play a highly significant role in the development of technical education in Sydney. A similar tale unfolded at Granville in the 1880s. A Granville School of Arts was first mooted by the Granville Progress Association in 1880. Its fine building on Good Street was completed in 1884. [48] That year, a group of Scottish engineers arrived in Sydney to work at the new rail workshop established by Hudson Bros near Granville. One of these engineers, James Brown, ran voluntary night classes for workshop apprentices at the Granville School of Arts. The Board of Technical Education soon recognised Brown's efforts and formalised his teaching role. By 1907 there were 279 students enrolled in technical classes at the Granville School of Arts, most of them drawn from local industry, and approval was given to build a new technical college. Brown [media]chose the site on South Street, Granville, for the erection of the Granville Technical College. [49] The College is now known as the Granville College of the South Western Institute of TAFE, and its origins can be traced directly to the Granville School of Arts.

Rational recreation

Richard Waterhouse, in his history of Australian popular culture, places schools of arts and mechanics' institutes 'at the heart of the movement for rational recreation', as part of the emergence of respectable culture in Australia in the mid-nineteenth century. [50] Debating clubs, public lectures and lending libraries were the officially sanctioned means by which schools of arts and mechanics' institutes promoted rational recreation in their communities. But arguably the institutes were also meeting this objective when they ran informal social events and leisure activities.

The Richmond School of Arts is a case in point. On 10 January 1866, the foundation stone was laid on a block of land formerly known as the 'pound paddock', on the corner of West Market and March Streets, Richmond. [51] At the ceremony, Reverend James Cameron, a Presbyterian clergyman and son-in-law of the School's president, gave a speech which went to the heart of the movement's moral improvement and rational recreation objective. It was reported in the newspaper of the day:

He hoped when the library and reading room have been fitted up that it would be a source of attraction to our young men and that they would be induced to spend their evenings in more profitable employment and in more befitting places than many of them do at present... He trusted that when its founders have passed away and been forgotten it would long continue to be a source of enlightenment and a centre of wholesome influences to the whole community. [52]

According to the Richmond School of Arts' current archivist, Ronald Rozzoli, these objectives are still being met a century and a half later. The library closed in 1957 but dance and theatre performances still regularly take place. The Richmond Players took up residence in the School of Arts in 1952 and today are the oldest continuously operating amateur theatre society in New South Wales. The Hawkesbury Valley Lapidary Club has maintained a workshop and exhibition facility in the school since the 1960s. [53] In earlier periods the school's facilities were used for public lectures with lanternslides and for meetings of the Richmond Borough Council and the Horticultural Society. There was fierce debate about whether public dancing should be allowed at the school but an early ban was overturned by a well-attended meeting in 1879; thereafter the school was a popular venue for social events. Billiards was another activity which stretched early definitions of rational recreation but again the committee relented and the billiard room was busy until the late 1940s.

Most schools of arts in Sydney found billiards to be a valuable source of revenue. In 1912, for example, the Rozelle Workingmen's Institute earned £1908 from its billiards table, which, as Roger Morris observes, was in those days 'more than enough to run a first-class community resource'. [54] Schools of arts came under criticism from some quarters for supporting such frivolous activities but others, such as New South Wales Premier Joseph Carruthers, defended this aspect of the institutes. While opening the Miranda School of Arts in 1904 he made a speech in favour of billiards, stressing the importance of recreation as well as education in the operations of successful schools of arts. As Roger Morris points out, 'the Schools' billiards rooms, card, smoking and other games rooms were some of the very few alcohol free zones where working men could meet and relax'. [55]

Lectures

In the nineteenth century, public lectures were like today's broadcast media; they were 'a major vehicle for enlightenment and for entertainment'. [56] Some skilled itinerant performers made the public lecture their stock in trade. They would pick subjects of great contemporary interest, use maps, diagrams and lantern slides and attract huge audiences to hear them speak at the local school of arts. In 1860 John Woolley described the attraction of such lectures at the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts:

... a season seldom passes which is not memorable for some lectures which would attract attention in the learned circles of London... we have been delighted by graphic narratives of personal observation in foreign lands, by clear elucidations of natural phenomena; by profound and original reflections of a master of the imagination and the higher reason. [57]

But as Woolley acknowledged, 'to this picture there is a reverse... it is not always easy to find ... people who have a real message to deliver year by year.' Lecture programs at schools of arts were, of necessity, frequently furnished by local people talking about their pet subject. Turnouts were often low, which, as Philip Candy notes, is not surprising given the esoteric nature of subjects, the dry mode of delivery and the fatigue of people after work. [58] Woolley lamented,

How often have I seen ... unhappy hearers sitting with stiff and desperate resolution – rigid in body, sorely straitened in mind... honest Christopher Sly's comment trembling on their tongues, 'a very good lecture this, Madam wife, would it were done...' [59]

Schools of arts and mechanics' institutes were pioneers of a local culture of debate and ideas in colonial Sydney. But clearly this wasn't an easy role in a frontier society where practical demands pressed on the energies of a small population more urgently than ideas.

Debates

Debating clubs and societies were an adjunct to some of the larger schools of arts. The Debating Club attached to the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts ran from 1844 until 1939. [60] It was an important venue for public debate, and a place where several public figures cut their teeth. In 1886, 1,200 people attended 41 meetings of the debating club, and in the following decade, working-class interest was strong. [61] Roger Morris observes that though the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts lost its large class program after the government took over its Technical and Working Men's College in 1883, 'its debating club remained an important forum for radical activity where the issues of economic depression, infant nationalism, federation and the birth of the ALP were strongly disputed'. [62]

In 1891 Louisa Lawson joined the club, overcoming fierce opposition from some members to participation by women, and opening the door for other outstanding female debaters such as Madame Eva Marie Wolfcarius. [63] Other high profile members of the Debating Club included Edmund Barton and William Holman. Meanwhile, Billy Hughes took part in debates at both the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts and the Balmain Workingmen's Institute.

Libraries

Some schools of arts formalised their technical education offerings and sponsored technical colleges which were later taken over by the state. Philip Candy refers to this as 'an interesting but by no means uncommon example of how local community initiative and self-help gradually gave way to Government provision of a needed service'. [64] Local libraries are another key example of this process. All over Sydney, the local municipal libraries often originated in the local schools of arts.

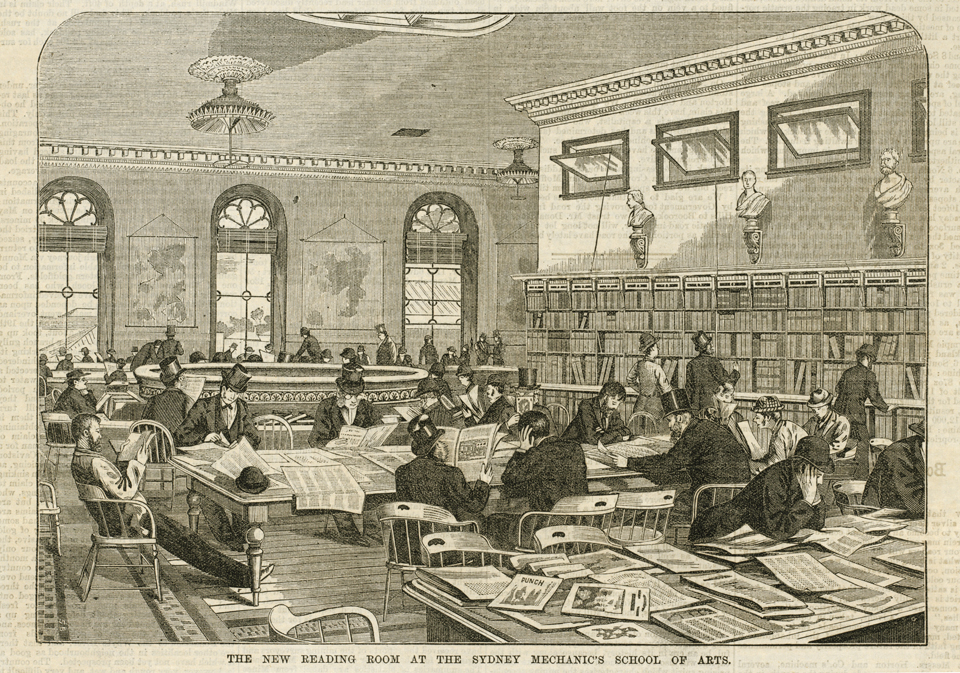

The provision of books, journals and newspapers for the use of members was a key function of schools of arts and mechanics' institutes. Even before an institute had a building, it had a library. Elaborate 'book box' schemes developed where books were exchanged and passed around between different institutes in the colony. [65] A government subsidy was available to schools of arts for the upkeep of the collection. The library function grew to be so important that schools of arts, especially after the turn of the century, were often known as literary institutes.

Committee minutes from institutes all over Sydney bear witness to the familiar struggle between the 'improvers' and the 'entertainers' over each library's collection policy. [66] This exchange at the 1895 Annual Meeting of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts is representative:

Vice-President Reid: The Committee finds that the great demand is for novels. There are many more who would read Trilby than would read Balfour's Foundations of Belief.'

Mr Langridge: But that is pandering to the wrong taste.

Mr Reid: It's our business to pander. (Loud applause.) [67]

At this time, 130,000 of the 150,000 books in the collection of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts library were fiction. In the case of Sydney's 'mother-school', the willingness to pander may have been a formula for success, since its library retained its autonomy and today has the distinction of being Australia's oldest lending library. [68]

However, in the new century, most schools of arts libraries were in a poor state, with random, increasingly shabby collections of light fiction. In 1912 a committee was set up to examine whether the subsidy paid annually by the New South Wales government to schools of arts and similar institutions was justified. The committee determined that it wasn't: book collections were meagre, especially non-fiction, and services were limited. The committee recommended phasing out subsidies in metropolitan areas and municipalities, and the takeover of schools of arts by local authorities

in accordance with the practice which obtains in the large cities of the old world, where Public Libraries are maintained and controlled by the Municipalities.

However, powerful local lobbying prevented these recommendations from being implemented. Government subsidies to schools of arts continued until the 1930s. [69]

In the mid-1930s the Australian Council on Educational Research and New York's Carnegie Corporation (which had an interest in Australian education) conducted a survey of Australian libraries. The result was the highly critical Munn-Pitt report of 1935: it found 'wretched little institutes which have long since become cemeteries of old and forgotten books'. [70] The report galvanised the Free Library Movement and led to the introduction of new public library legislation in all states, [71] with the New South Wales Library Act 1939 being eventually proclaimed in 1944. Over the following decade and a half, the library collections of most Sydney schools of arts were taken over by municipal councils.

Cinemas

Les Tod is a historian of movie theatres who has uncovered the little-known but important role that schools of arts played in Australian cinema history. [72] Cinema came to Australia in 1896 but only really took off in the period from 1905 to 1912. There were no movie theatres at that time, and only a few live theatre venues in Sydney, so schools of arts and public halls were often used for screenings. Itinerant showmen brought their films and hired these venues to show them. Blacktown is a good example. Films became so popular at the Blacktown School of Arts that by the early 1920s it was clear that a permanent movie theatre was needed. Blacktown's first purpose-built cinema opened in 1922, surprisingly early for what was then a small rural community. That theatre was soon replaced, and since then it has in turn been replaced by a multiplex. But cinema started in Blacktown at the School of Arts. [73]

A woman's place?

Ellen Elzey, who has looked closely at the involvement of women in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, notes that the data for Australian institutes regarding women's involvement is patchy. However she has turned up some telling information about the history of women's participation in Sydney's first institute. [74]

The first three female members of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts were admitted in August 1833, just months after the School's establishment. They were all married to men who were prominent at the School: Maria Windeyer, Jane Cape and Emma a'Beckett. Membership was overwhelmingly male until about 1950, when women made up 48 per cent of the membership.

Women certainly attended lectures at the School. John Armstrong took his wife and her sister to a lecture on Electro-Biology in 1853, noting it in his diary. Women's names start appearing in class rolls in the 1860s. In 1864 the Ladies' Drawing Class was the first class exclusively for women.

The School's [media]annual report of 1861 reveals that a table had been set up in the library for the exclusive use of 'lady members'. When the building was remodelled a few years later, a separate Ladies' Reading Room was created. Perhaps these developments were in line with the views the School's Vice-President John Woolley expressed in a speech in 1860:

I have one serious fault to find with... our institution – the reading room [is] confined to the male sex... I believe the most formidable amongst our social dangers is the increasing separation of our young men from the companionship of pure and refined women. Until we can strike this evil to the heart, all efforts are worse than vain to check intemperance and immorality. [75]

If so, women were granted access to library not out of concern for equal rights, but rather a desire on the part of the School's management to introduce a civilising influence.

By the early twentieth century, women were giving lectures, and commenting on them. Adela Pankhurst, who carried a famous feminist name, spoke at the School in 1933. Miles Franklin recorded in her diary of 30 August 1933:

Went at 3 to the School of Arts to hear Adela Pankhurst. Am convince [sic] she is a moron – she babbles – without coherence. [76]

[media]In 1893 Louisa Lawson was the first woman elected to the committee of management. According to her biographer Brian Matthews, she later resigned in protest against the nit-picking and circumlocutory discussions that meant no action ever resulted from any meeting. In 1994 the School appointed its first female Vice President, and later that year its first female Secretary. [77]

Further research is required to examine women's involvement in other schools of arts and mechanics' institutes around Sydney. In many of the second wave institutes, including the Peakhurst School of Arts and the Bondi-Waverley School of Arts, a ladies' committee took charge of catering, fundraising events and decorating the premises for different functions. [78]

Heyday no more

[media]By the middle of the twentieth century, it wasn't just the book collections of Sydney schools of arts that were being taken over by local municipal councils. In many cases the institutes' premises were being transferred to the council, and the historic organisations were folding. A City of Sydney Minute Paper dated 17 September 1956 reports on the opening of the Glebe Branch of the City of Sydney Public Library. The document recounts that the new library replaced the Glebe School of Arts:

On 26th October 1953... Council agreed to take over from the Trustees of the Glebe School of Arts the library, together with the land and premises at 191–195 Bridge Road, Glebe, for the purpose of controlling and managing such library as a Branch of the City of Sydney Public Library ... [In early] 1955 ... final settlement took place and the above land and property were placed under the trusteeship of the Council. [79]

A similar process occurred in many municipalities across Sydney from the 1950s to the 1980s. Sometimes the councils have retained the premises as community facilities, as in Arncliffe and Rockdale. Frequently they were sold and in many cases the buildings were demolished, as in Blacktown and Chatswood. In Glebe, the old School of Arts premises on Bridge Road were eventually sold and redeveloped as a block of residential units.

The education role of schools of art, always tenuous, had become irrelevant as formal adult education systems expanded. As Warburton observed in 1963, in this regard schools of arts

have been taken over by official education departments, University Extension Boards and Adult Education Departments, the WEA, a free library system and a municipality of clubs and societies which provide for the specialised educational needs of contemporary Australians. [80]

Several other factors contributed to the demise of the majority of greater Sydney's schools of arts. Their financial viability was undermined during the 1930s depression when the government reduced, then ended, their annual subsidies. Later, the proliferation of licensed clubs meant fewer people made use of the institutes' revenue-raising billiards tables. Meanwhile, recreational interests were increasingly captured by movie theatres, and later by television. As local populations grew, more specialised community services and facilities developed. The advent of the motor car created a suburban population both less tied to the local community and more home-oriented. New council-run public libraries with up-to-date collections and trained staff soon made the older, more limited collections of the institutes' subscription libraries redundant. [81]

About 17 Sydney schools of arts are still operating independently. [82] Apart from the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, these include Cronulla, Richmond, Carlton, Leichhardt and Guildford.

Utility, not greatness

For more than a century in Sydney, local schools of arts and mechanics' institutes contributed significantly to the social, recreational and even educational lives of their communities. Only a small percentage of these institutes survive today, but their legacy can be seen in the city's network of local public libraries, neighbourhood centres and the state system of technical education.

The multipurpose second-wave institutes in Sydney did not correspond to the vision outlined by the movement's founders in the United Kingdom, which saw the institutes as vehicles for the diffusion of scientific knowledge and the moral improvement of the working man. If we are to measure the movement's success in these terms, observes Roger Morris,

then the Australian Institutes' billiard tables, libraries of popular fiction, light entertainment, lowbrow lectures, useful classes and regular dances can be seen as blatant examples of this tragic failure.

Instead, suggests Morris, they can be read as successful for having adapted the idealism of the movement's founders to meet the real needs of their local communities. [83] Philip Candy concurs:

Older residents invariably speak fondly, and local historians write, of the institute as the hub of community life, a place where… people met to play cards or chess or billiards, to cook and to sew, to send people away to war and to welcome them home again, and even to keep themselves warm in the depression. While these activities may seem trivial to educational purists, they are vital to the ebb and flow of life in a community... [84]

Warburton saw the achievement of the School of Arts movement as being the articulation of the needs of a rapidly changing technological society. He gives the movement credit also for 'what it initiated, in trying to meet these needs: technical education, general and scientific adult education, industrial museums, libraries and public debate. [85]

Rev Dr John Woolley's words from 1860 still ring true:

It may be that we have traced a plan which our posterity alone can complete. We have not the less done a good work, if the edifice be in itself useful, and capable of adequate extension... our watchword is utility, not greatness. [86]

References

Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002

Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000

Roger Morris, 'Learning after work one hundred years ago: Workingmen's Institutes in inner city Sydney' at www.aicm.edu.au/files/Roger_Morris-Workingmens_Institutes.pdf, viewed 3 May 2010

Notes

[1] Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 85

[2] See Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, pp 5–10

[3] Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 7

[4] Frederick Maitland Innes, 'A lecture delivered before the members of the Hobart Town Mechanics' Institution; on the advantages of the general dissemination of knowledge, especially by mechanic, and kindred institutions', SA Tegg, Hobart Town 1838, p 18

[5] Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 7

[6] Frederick Maitland Innes, 'A lecture delivered before the members of the Hobart Town Mechanics' Institution; on the advantages of the general dissemination of knowledge, especially by mechanic, and kindred institutions', SA Tegg, Hobart Town 1838, pp 23–5

[7] Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, pp 5–6

[8] Patrick N O'Farrell, 'A Pioneering Mechanics' Institute: Foundation of the Edinburgh School of Arts' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, pp 12–13

[9] Professor Pillans in Sixth Report of the Directors of the School of Arts of Edinburgh for the Instruction of Mechanics in such branches of physical science as are of practical application in their several trades, August 1827, pp 4–5

[10] John Archibald Murray, Esq, in Sixth Report of the Directors of the School of Arts of Edinburgh for the Instruction of Mechanics in such branches of physical science as are of practical application in their several trades, August 1827, p 7

[11] Roger Morris, 'Mechanics' Institutes in the United Kingdom, North America and Australasia: A Comparative Perspective' in Jost Reischmann, Michal Bron Jr (eds), Comparative Adult Education 2008: Experiences and Examples, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, 2008, pp 179–190

[12] Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria,, 2000, p 5

[13] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 3

[14] Alex Tyrell, 'British origins of Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 5

[15] Philip Candy, 'Australian Mechanics' Institutes' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 21

[16] Elisabeth Richardson, 'Survey of Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes in New South Wales', unpublished list supplied by Elisabeth Richardson to the author – these counts are approximate and do not include all institutions surveyed by Richardson, only those called Schools of Arts, Free Public Libraries or Workingmen's, Literary or Mechanics' Institutes

[17] Henry Carmichael, 'Introductory lecture delivered at the opening of the twelfth session of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts on the 3rd of June, 1844' Sydney: Kemp and Fairfax 1844, p 3

[18] Vernon Crew, 'Henry Carmichael' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, p 13

[19] Henry Carmichael, 'Introductory lecture delivered at the opening of the twelfth session of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts on the 3rd of June, 1844' Sydney: Kemp and Fairfax 1844, pp 4–5

[20] Page from the minute book recording the first General Meeting of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts, 22 March 1833, Mitchell Library manuscripts ZA4147

[21] Sydney Herald, 21 March 1833, cited in Roger Morris, 'The Working Men's College 1878–83: The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts and the formal establishment of technical education in New South Wales' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 36

[22] Roger Morris, 'Australia's oldest adult education provider: The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts on the occasion of its 165th birthday' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, pp 24–5; Joan Beddoe, 'Mechanics Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia' in Aplis, vol 16, no 3, September 2003, p 124

[23] Elizabeth Webby, 'Dispelling 'the stagnant waters of ignorance': the early institutes in context' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds) Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, pp 30–31

[24] George Allen to Joseph Allen, 15 February 1820, cited in Elizabeth Webby 'Dispelling 'the stagnant waters of ignorance': the early institutes in context' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 29

[25] Elisabeth Richardson, 'Survey of Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes in New South Wales' unpublished list supplied by Elisabeth Richardson to the author – the foundation dates for many institutes have not yet been ascertained so actual number of institutes established before 1900 is likely to be bigger than 40

[26] John Woolley, 'The Social use of Schools of Art, delivered in the Mechanics' School of Arts, Sydney, at the commencement of the lecture season, May 1, 1860' in John Woolley, DCL, Lectures delivered in Australia, Macmillan and Co, Cambridge and London, 1862, p 343

[27] Henry Carmichael, 'Introductory lecture delivered at the opening of the twelfth session of the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts on the 3rd of June, 1844' Sydney: Kemp and Fairfax 1844, p 5

[28] Shirley Fitzgerald and Christopher Keating, Millers Point: The Urban Village, Halstead Press, Sydney, 2009, p 29

[29] Vernon Crew, 'Henry Carmichael' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, pp 13–14

[30] Cited in JW Warburton, 'Schools of Arts' in Australian Quarterly, vol XXDXV, no 4, Dec 1963, p 74

[31] Vernon Crew, 'Henry Carmichael' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, p 14

[32] Derek Whitelock, The Great Tradition: A History of Adult Education in Australia, UQP, St Lucia, 1974

[33] Roger Morris, 'Learning after work one hundred years ago: Workingmen's Institutes in inner city Sydney' at www.aicm.edu.au/files/Roger_Morris-Workingmens_Institutes.pdf, viewed 3 May 2010, p 4

[34] Roger Morris, 'Learning after work one hundred years ago: Workingmen's Institutes in inner city Sydney' at www.aicm.edu.au/files/Roger_Morris-Workingmens_Institutes.pdf, viewed 3 May 2010, pp 5–6

[35] Roger Morris, 'Learning after work one hundred years ago: Workingmen's Institutes in inner city Sydney' at www.aicm.edu.au/files/Roger_Morris-Workingmens_Institutes.pdf, viewed 3 May 2010, p 6

[36] See map showing the religious distribution within Sydney and suburbs 1901 from Richard Broome, Treasure in Earthen Vessels: Protestant Christianity in New South Wales Society 1900-1914, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia Qld, 1980

[37] Correspondence with Elisabeth Richardson, December 2009

[38] Geoffrey Serle, The Creative Spirit in Australia: A Cultural History cited in Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 78

[39] Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 79

[40] Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 79

[41] See James William Hudson, A History of Adult Education, Longman, Brown Green, London 1851

[42] Patrick N O'Farrell, 'A Pioneering Mechanics' Institute: Foundation of the Edinburgh School of Arts' in Rediscovering Mechanics' Institutes: Australian Mechanics' Institutes Conference 2000, Local Government Division, Department of Infrastructure, State Government of Victoria, 2000, p 17

[43] Vernon Crew, 'Henry Carmichael' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, p 14

[44] Joan Beddoe, 'Mechanics Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia' in Aplis, vol 16, no 3, September 2003, p 123

[45] Norm Neill, Technically & Further: Sydney Technical College 1891–1991, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991, p 9

[46] New South Wales Department of Technical and Further Education, Spanners, Easels & Microchips: A History of Technical and Further Education in New South Wales 1883–1983, New South Wales Council of Technical and Further Education, Sydney, 1983, p 11

[47] see Norm Neill, Technically & Further: Sydney Technical College 1891–1991, Hale & Iremonger, Sydney, 1991

[48] 'School of Arts Building' in The Granville Guardian, vol 13 no 1, Jan 2006, Granville Historical Society Inc, p 3

[49] 'The history of Granville College' at www.swsi.tafensw.edu.au/aboutswsi/colleges/granville.aspx

[50] Richard Waterhouse, Private pleasures, public leisure: A history of Australian popular culture since 1788, Longman Australia, Melbourne 1995, ch4

[51] Ronald Rozzoli, 'Richmond School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 97

[52] Unattributed newspaper clipping pasted into the 1866 minute book for the Richmond School of Arts

[53] Ronald Rozzoli, 'Richmond School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, pp 100–101

[54] Roger Morris, 'Learning after work one hundred years ago: Workingmen's Institutes in inner city Sydney' at www.aicm.edu.au/files/Roger_Morris-Workingmens_Institutes.pdf, viewed 3 May 2010, p 3

[55] Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 80 and p 83

[56] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 9

[57] John Woolley, 'The Social use of Schools of Art, delivered in the Mechanics' School of Arts, Sydney, at the commencement of the lecture season, May 1, 1860' in John Woolley, DCL, Lectures delivered in Australia, Macmillan and Co, Cambridge and London, 1862, p 349

[58] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, pp 9–10

[59] John Woolley, 'The Social use of Schools of Art, delivered in the Mechanics' School of Arts, Sydney, at the commencement of the lecture season, May 1, 1860' in John Woolley, DCL, Lectures delivered in Australia, Macmillan and Co, Cambridge and London, 1862, p 350

[60] Ellen Elzey, 'A Woman's Place? An overview of female participation in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 34

[61] JW Warburton, 'Schools of Arts' in Australian Quarterly, vol XXDXV, no 4, Dec 1963, p 78

[62] Roger Morris, 'Australia's oldest adult education provider: The Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts on the occasion of its 165th birthday' in Mechanics' Institutes of Australia, Learning Circles Australia 2001, p 27

[63] Ellen Elzey, 'A Woman's Place? An overview of female participation in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, p 34

[64] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 12

[65] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, pp 8–9

[66] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 9

[67] Cited in JW Warburton, 'Schools of Arts' in Australian Quarterly, vol XXDXV, no 4, Dec 1963, p 78

[68] The Carlton School of Arts library is another Sydney institute also notable for the longevity of its library collection. According to the Heritage Branch of the New South Wales Department of Planning, the Carlton School of Arts disposed of its library collection as late as 1996. See www.heritage.nsw.gov.au/07_subnav_01_2.cfm?itemid=5053088

[69] David J Jones, 'Public library development in New South Wales' in The Australian Library Journal, vol 54, no 2, May 2005

[70] R Munn and E R Pitt Australian libraries: a survey of conditions and suggestions for their improvement, Australian Council for Educational Research, Melbourne 1935 p 24

[71] Peter Biskup, 'Australia' in Wayne A Wiegand and Donald G Davis Jr (eds), Encyclopedia of Library History, Garland Pub, New York 1994, p 51

[72] See Ross Thorne, Les Tod and Kevin Cork, A Cultural Heritage of the Movie Theatres of New South Wales, Department of Architecture, University of Sydney, 1996

[73] Conversation with Les Tod, August 2009

[74] This sub-section, draws heavily upon Ellen Elzey, 'A Woman's Place? An overview of female participation in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney 2002, pp 31–35

[75] John Woolley, 'The Social use of Schools of Art, delivered in the Mechanics' School of Arts, Sydney, at the commencement of the lecture season, May 1, 1860' in John Woolley, DCL, Lectures delivered in Australia, Macmillan and Co, Cambridge and London, 1862, p 357

[76] Cited in Ellen Elzey, 'A Woman's Place? An overview of female participation in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, UTS 2002, p 34

[77] Ellen Elzey, 'A Woman's Place? An overview of female participation in the Sydney Mechanics' School of Arts' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, pp 34–5

[78] Brian Shaw (compiler), Peakhurst School of Arts: A Firm Foundation, The Trustees, Peakhurst School of Arts Inc, 1999?, p 8; Bondi-Waverley School of Arts, Fourth annual report and balance sheet, 1915, p 11

[79] City of Sydney Archives 3999/56 Minute paper, Town Clerk's Department, 17 September 1956

[80] JW Warburton, 'Schools of Arts' in Australian Quarterly, vol XXDXV, no 4, Dec 1963, p 80

[81] Roger Morris, 'Sydney suburban Schools of Arts: From and for the community' in Schools of Arts and Mechanics' Institutes: From and for the community – Proceedings of a National Conference, University of Technology, Sydney, 2002, pp 84–5

[82] Information supplied by Richard Papis of the New South Wales Land and Property Management Authority, from an audit undertaken by the then Department of Lands in 2006. The New South Wales Land and Property Management Authority does not know precisely how many institutes are still operating under the terms of the original Trustees of Schools of Arts Enabling Act 1902 as there are no formal reporting requirements of Schools of Arts trustees

[83] Roger Morris, 'Mechanics' Institutes in the United Kingdom, North America and Australasia: A Comparative Perspective' in Jost Reischmann, Michal Bron Jr (eds), Comparative Adult Education 2008: Experiences and Examples, Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main, 2008

[84] Philip Candy, ''The light of heaven itself': The contribution of the institutes to Australia's cultural history' in Philip Candy and John Laurent (eds), Pioneering Culture: Mechanics' Institutes and Schools of Arts in Australia, Auslib Press, Adelaide 1994, p 14

[85] JW Warburton, 'Schools of Arts' in Australian Quarterly, vol XXDXV, no 4, Dec 1963, pp 79–80

[86] John Woolley, 'The Social use of Schools of Art, delivered in the Mechanics' School of Arts, Sydney, at the commencement of the lecture season, May 1, 1860' in John Woolley, DCL, Lectures delivered in Australia, Macmillan and Co, Cambridge and London, 1862, p 346

.