The Dictionary of Sydney was archived in 2021.

Phillip’s Table: Food in the early Sydney settlement

Citation

Persistent URL for this entry

To cite this entry in text

To cite this entry in a Wikipedia footnote citation

To cite this entry as a Wikipedia External link

Phillip’s Table: Food in the early Sydney settlement

[media]When considering food in the early settlement of New South Wales, acknowledgement must be given to the Aboriginal peoples whose expert care and sustainable management of the land facilitated the British colonists' survival. While the land may have seemed to outsiders be an inhospitable or even hostile wilderness, had it not been groomed, tended and nurtured by its local peoples, the colonisers would have faced a much more difficult task in establishing themselves in this place.

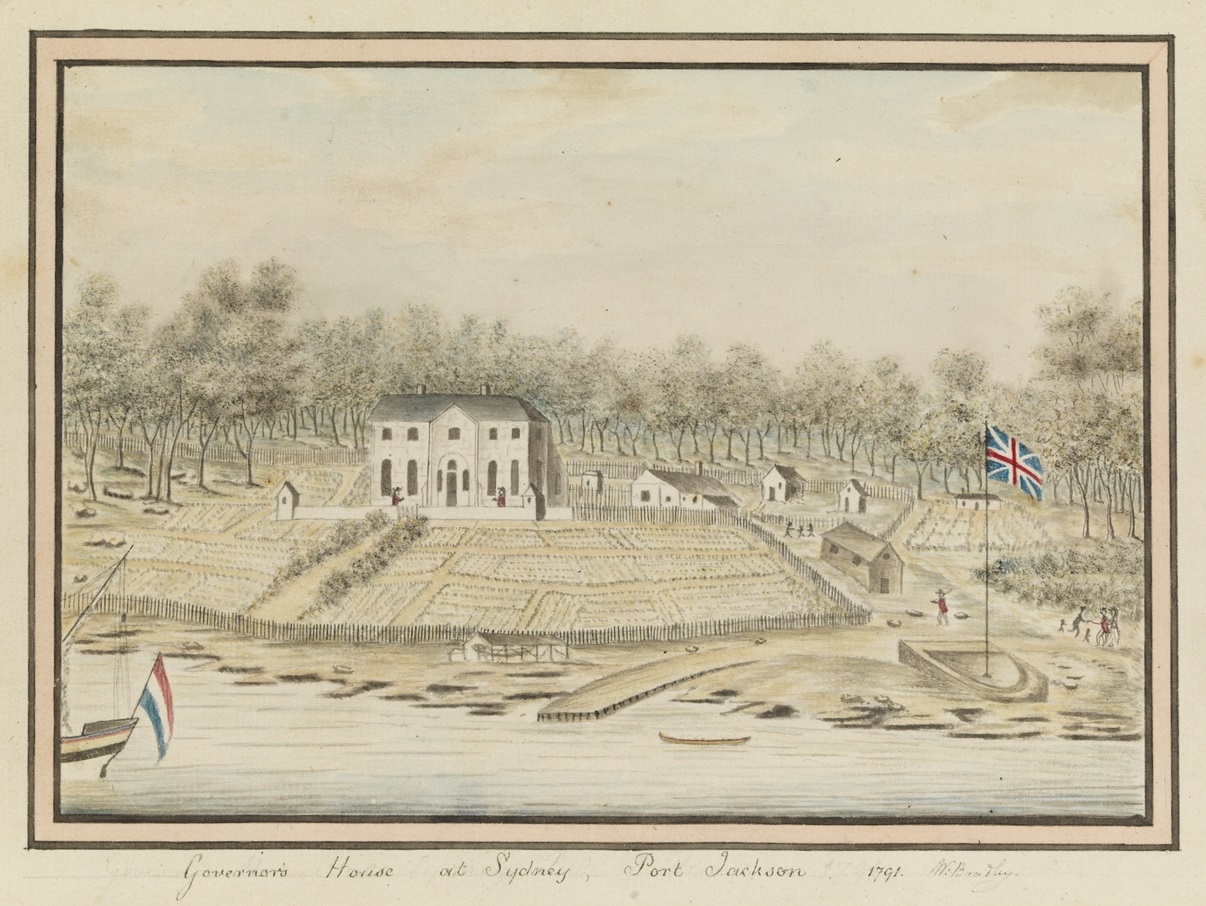

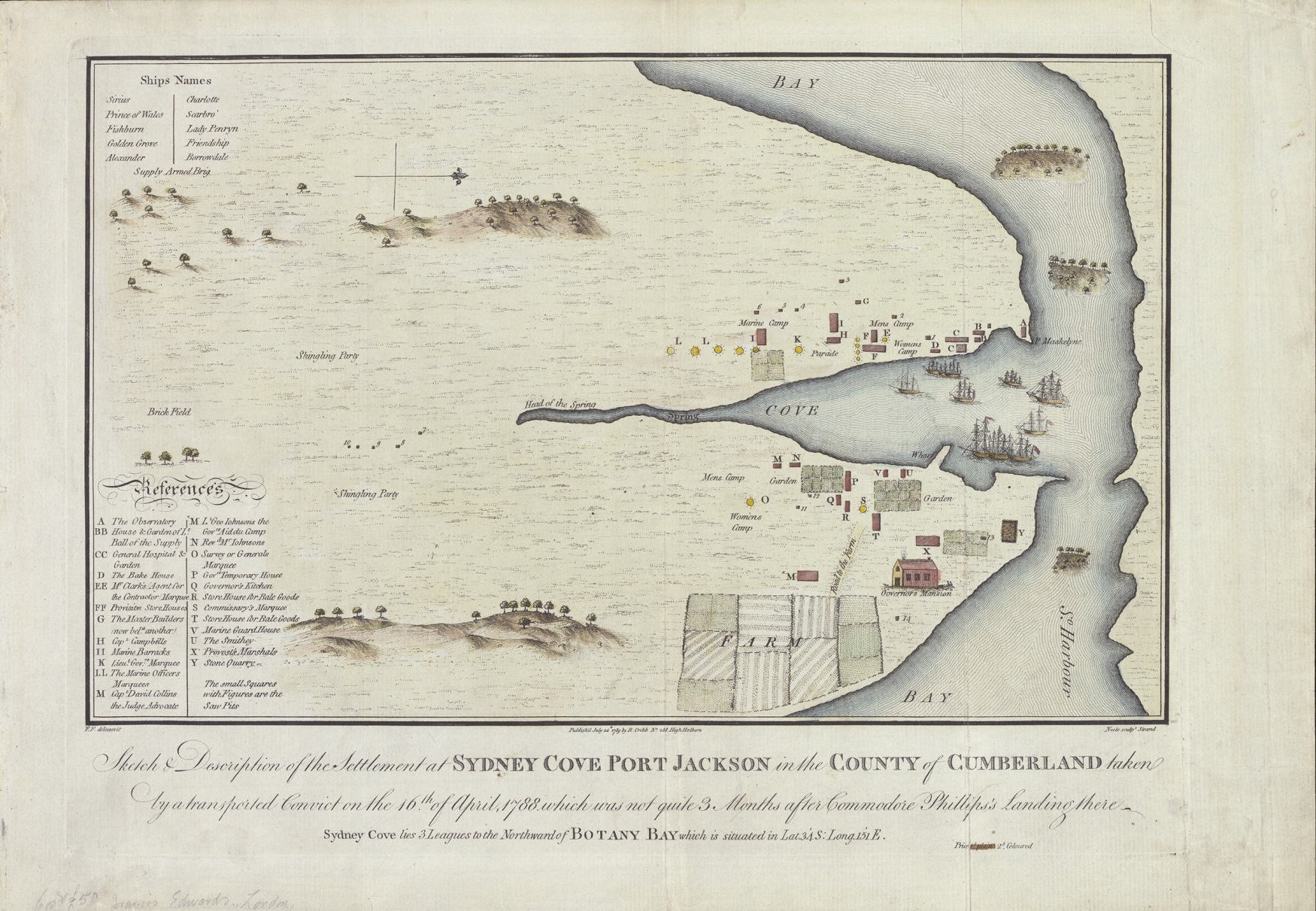

[media]Sydney's first Government House was Governor Arthur Phillip's home and its residents, his 'family' (as they were often referred to by contemporary diarists), included a small group of household servants. Among them was agriculturalist, Henry Dodd, the colony's head gardener who would later transfer to Parramatta, and Phillip's personal servant, Bernard de Maliez. In time, members of Aboriginal communities would join the governor's family, in various capacities.

Maintaining sociable British civil practices and protocols, the colony's principal players, senior officers and key personnel would regularly dine or take tea at the governor's house. The governor's table was a place for administration, negotiation, revelation and celebration.

King's birthday feat in 1788

There are few explicit, let alone descriptive, references to meal events at Government House, or in Phillip's company. But there are myriad clues, glimpses, snippets and teasers in extant journals. One of the most revealing is from First Fleet surgeon George Worgan. Worgan was quite the gourmand and bon vivant, and described in his journal the celebratory feast enjoyed by Phillip and his officers on the King's birthday on June 4, 1788:

[At] about 2 O'Clock We sat down to a very good Entertainment, considering how far we are from Leaden–Hall [the London] Market, it consisted of Mutton, Pork Ducks, Fowls, Fish, Kanguroo, Sallads, Pies & preserved Fruits… The Potables consisted of Port, Lisbon, Madeira, Teneriffe and good old English Porter, these went merrily round in Bumpers… [E]very Gentleman standing up & filling his Glass, with one Voice gave, as the Toast, The Governor and the Settlement, We then gave three Huzza's, The Band playing the whole Time.[1]

The meal finished around five o'clock, and after a turn about the settlement to witness the hoi polloi's festivities, the officers returned to Government House for supper, finally calling it quits around 11pm, to return to their designated lodgings or ships cabins. While not all meals would have been so lavish, this menu illustrates the range of foods available to the colonists, barely six months after arriving in Port Jackson.

In fact we have a good idea of the types of foods available in the colony in Phillip's time. These can be grouped into three distinct categories: government controlled salt provisions, popularly known as 'rations'; farmed produce, raised by the colonists themselves in public gardens and in individual, privately tended plots; and native foods, foraged from the bush or shoreline, or hunted. Significant catches, such as kangaroo or seine-caught fish were under the jurisdiction of government, while smaller finds such as shellfish, eel, wild birds or small marsupials were generally allowed to remain with those lucky or plucky enough to procure them.

Rations

[media]Synonymous with convicts and the first settlement period are the rations, which were based on long-standing British naval practices. All colonists, regardless of rank or status, were entitled to receive an allocation of salted meat, flour or biscuit, peas and rice. But Phillip upheld strict policies about entitlement; food was an earned right – no work, no food. He also understood that food was fuel for his labouring force. There was no benefit to be had in underfeeding them. There were strict orders that food must not be traded, but without a cash economy, food became a principal form of currency and a healthy black market operated regardless.

To the marines' chagrin, Phillip adhered unswervingly to the parity policy set by Treasury and the Navy Board which had both convict and 'free' people receiving the same issue, except for a half pint of rum which was denied to convicts. Women of all classes received two-thirds of the standard allocation but when depleted stores induced reductions in the ration, Phillip ordered that the women’s allowance be left intact, and they received the same as their male counterparts. This is indicative of Phillip's 'enlightened' political views and paternal style of governance.

While rations may have satisfied caloric intake (over 14000 kilojoules or 3000 calories per day, equivalent to current Australian dietary recommendations for a labouring man) salt provisions were not nutritionally balanced, with an obvious lack of fresh greens.

Farmed produce

[media]The list of plants and seeds, livestock and poultry brought from England, Rio de Janeiro and the Cape of Good Hope with the fleet is extensive. There was much experimentation to see which species would prove suitable for the new locale. The strongest focus for public gardens was to establish a supply of grain for bread (wheat, or maize as an alternative) and hardy high-yielding vegetables such as cabbages, potatoes and turnips.

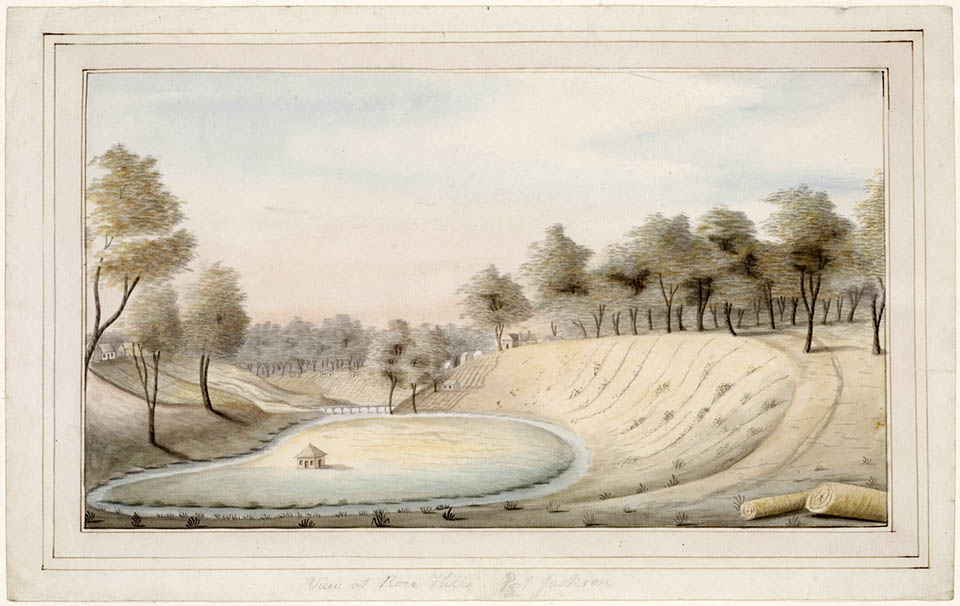

[media]Convicts were encouraged to establish their own vegetable gardens. They were provided with seeds and allocated time off to tend them, though some preferred to help themselves to others' efforts. It was soon recognised that Sydney’s sandy soils were unsuited to raising European style crops, and gardening efforts turned to the richer soils around Parramatta.

[media]Gardens take time to become productive, and colonists naturally turned to wild produce that seemed similar to conventional European species – purslane, wild sage, celery, 'spinnage' and samphire, the native herb Smilax glyciphylla, which was used as tea, and wood-cabbages from the cabbage palm. Colonists' extractive, exhaustive approach to useful resources meant that many were quickly exhausted, including the cabbage palm, of which, it was reported that within months of landing 'we have not left one within a dozen of miles of us.'[2]

Extant letters and journals show that native resources were valued and actively sought out to supplement the government stores and to preserve the imported livestock which were prized as breeding stock. People were keen to add native foods to their diet, not simply because of hunger, as is often given as a reason for consuming native produce. They were valued for their nutritive and medicinal qualities, and for variety and freshness.

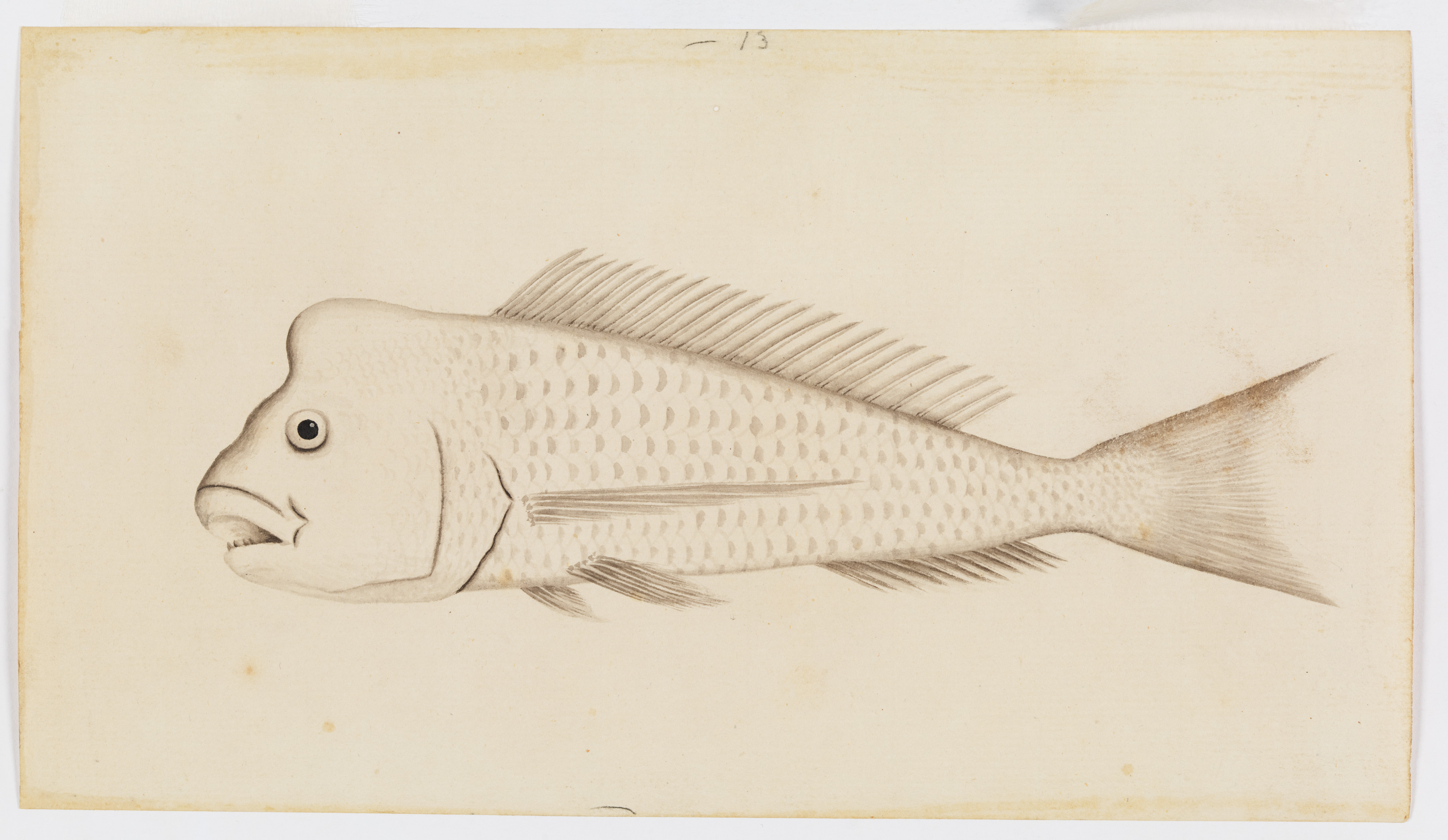

Native resources

There are many known instances of colonists' experimentation with, and indeed enjoyment of, native produce – aquatic creatures such as eels, stingrays and turtles, birds and their eggs, game animals, even grubs and reptiles. While some native fauna seem to us unconventional culinary resources we must not apply our modern food prejudices to past practices. A wide range of foods found their way into the colonists' pots, partly through the colonists' curiosity, perhaps from 'sailors' tastes' (opting for anything fresh over salted alternatives) but also due to eighteenth-century British practices. Period cookbooks show that game and wild food were commonly found on British tables. Some people were willing to risk a penalty to obtain fresh game, as one colonist revealed in 1791:

the opossum, of which there is a great number…eat very well…we sometimes get…cangaroos…to buy for sixpence per pound, but it must be done privately, as the governor will not allow it.[3]

'Bring your own bread'

The fleet carried what was calculated to be two years supply of provisions, but by late 1789, Phillip began to doubt the arrival of replenishment stores as promised. Lean times came with the not-yet-understood loss of HMS Guardian, which hit an iceberg en route in December 1789 while laden with food and other provisions for the colony. Phillip responded to growing fears with a number of strategies, including the reduction of the rations allocation for all adults to half the standard ration, transferring 280 people to Norfolk Island to alleviate pressure on local produce, and planning a mercy dash for provisions to Canton, China, by HMS Sirius, one of the two ships servicing the colony. The Sirius was wrecked, however, delivering convicts and supplies to Norfolk Island, adding to both colonies' woes from March 1790.

Phillip transferred his personal supply of flour, three hundred weight (cwt;150 kilograms), to the Commissary for the public benefit (which contributed about two weeks ration for the 600 people remaining in Sydney) and declared,

that he wished not to see anything more at his table than the ration which was received in common from the public store… and to this resolution he rigidly adhered, wishing that if a convict complained, he might see that want was not unfelt even at Government house.[4]

The now famous catch-cry 'bring your own bread' was born, where 'even at the governor's table, this custom was constantly observed. Every man when he sat down pulled his bread out of his pocket, and laid it by his plate.'[5]

Phillip's donation of his personal stores was not simply a noble act. Along with maintaining the parity policy between classes it was a prudent political and leadership strategy. Phillip would have been very conscious of the 'power of the mob' and plebeian uprisings over rights to food in eighteenth century England, and echoed in the 'let them eat cake' situation that unfolded in France.

Bennelong

[media]Bennelong, the Aboriginal man who had been kidnapped on Phillip's orders in November 1789, was at this time living as a captive at Government House. His keepers feared that if Aboriginal peoples became aware of the colonists' tenuous food situation, they would take advantage of the beleaguered settlers' 'reduced state':

We knew not how to keep him, and yet we were unwilling to part with him. His allowance was regularly received like that of any other person, but the ration of a week was insufficient to have kept him for a day. Had he penetrated our state [of dearth]…and diminished strength, [his people might have] become more troublesome Every expedient was used to keep him in ignorance.[6]

The colonists were hungry, vulnerable, and nervous.

To the officers' disappointment, Bennelong escaped from Government House in May 1790, and he stayed away from the settlement until after the spearing of the governor in September 1790 at Manly Cove, now recognised as an Aboriginal ‘payback’ ritual.

Facing famine

There has been much criticism of colonists' suffering scarcity and hunger in a land of abundance. Within two years of settlement the colony faced the prospect of famine and starvation on land that had supported Aboriginal communities for thousands of years. It seems imprudent that Phillip did not make better use of native food resources, and was so dependent on a food supply that needed to be transported across the globe. The nature and inconsistencies of native foods, however, meant that they weren't suited to the rationing systems that the colonising model for New South Wales was based upon.

[media]Food historian Barbara Santich states that 'food represents the myths and mores, the priorities and practices of a society.'[7] As indicated by the symbols of agricultural productivity on the colony's first territorial seal (endorsed in 1790) the priorities and practices of this early Sydney society were to establish a permanent European style settlement based on agriculture. The seal depicts convicts having their fetters removed before 'Industry', who sits on a bale of goods, a pick axe and spade, a distaff (for spinning flax or wool), oxen ploughing and a bee hive, the latter items all relating to agricultural production.[8]

There were logistical and organisational factors that must also be considered. To develop its infrastructure, the colony's labour systems were intrinsically linked to the ready supply of preserved food staples. Firstly, in a 'gaol without walls', food was a useful form of social control. The authorities did not want convicts to think they could survive beyond the settlement; control the food supply and you control your people.

Further, systematic hunting and foraging for shellfish, wild animals and edible vegetation were impediments to the progress of colony building. Foraging in the bush was dangerous, exposing settlers to attack from Aboriginal people who were not happy about the Europeans' extractive activities and invasion of their territories. This provided further control and security advantages for the authorities, who did not want their labour force to roam. Also, hunting requires weapons or firearms and fishing requires boats – neither of which the authorities wanted to entrust to convicts.

Economy of scale is another consideration. Despite the region's reputation for abundance, hunting, foraging and gathering for a permanent population of up to 1,000 people would not be sustainable. The limited number and the distribution of Aboriginal family groups across such a vast area makes this evident.[9] The impact of extractive and homogeneous hunting and harvesting practices concentrated around the settlement areas placed pressure on local resources, especially on species favoured by the immigrants.

[media]Distributing fresh, perishable food, especially fish or fresh greens, to 1000 people a day was also impractical. Fish was sometimes given out in lieu of salt provisions but even large catches made little real saving to the government stores. Despite the supposed monotony and tedium of salt provisions, people held fish in low regard if it meant a reduction in their salt–meat allocation, which could be stored and perhaps traded, albeit illegally.

On an individual scale, however, the primary records give many examples of colonists actively engaging with the environment and a willingness to try native produce, sometimes with the assistance of Aboriginal people. Judge-advocate David Collins, for example, wrote of his own disgust at the eating of witchety–type grubs, but tells us that one of his servants, 'a European, had often joined the Aborigines in eating this luxury; and has assured me, that it was sweeter than any marrow he had ever tasted.'[10] This account indicates an active cross-cultural exchange between members of both cultures, indigenous Australians and settlers; a shared table.

Contested territory

According to colonists' journals there were periods where Aboriginal people were hungry too. The increase in population put extra pressure on Aboriginal food resources, especially fish. Even modest seine-net hauls would have had significant impact on the Aboriginal peoples' supplies. But it has also been suggested that while there was contested territory, the two cultures had differing food preferences.[11] In Phillip's time, the colonist population was concentrated around the Sydney Cove and Parramatta settlements, with additional activity in various parts of the harbour and waterways. Aboriginal people, however, could cover a much greater area in search of food, and the arrival of the coloists pushed them beyond their traditional territorial boundaries; nonetheless, the colonists' journals suggest that in this place of abundance there were times when Aboriginal communities experienced seasonal shortages.

Was it from necessity, or their own form of 'payback', or simply exercising a rightful claim, that Aboriginal people began to frequent the settlement towards the end of 1790, many of them seeking accommodation, as well as food and other commodities?[12] Indeed, Bennelong may well have recognised this as an advantage in re-opening and developing relations with Phillip after the infamous spearing.[13] Tench lamented,

With the natives we are hand and glove. They throng the camp every day, and sometimes by their clamour and importunity for bread and meat (of which they now all eat greedily) [they have] become very troublesome God knows, we have little enough for ourselves.[14]

It seems that the tables had turned, with Aboriginal people now putting pressure on the colonists' food supplies.

Phillip established an open door policy and Aboriginal people from varying districts became a regular feature in the settlement. Many used Government House as their 'headquarters', camping in the 'yard', where they were supplied with bread and rice from the government stores and fresh fish. For others, Phillip's house became a temporary refuge during personal or tribal disputes, and others stayed there more permanently, lodging with the governor's servants.[15]

Many colonists were disgruntled at Phillip's policy of inclusion and resented the Aboriginal people being supplied with food. Convict painter Thomas Watling wrote,

Many of these [Aboriginal people] are allowed a freeman's ratio of provision for their idleness [While we] are frequently denied the common necessities of life they are treated with the most singular tenderness.[16]

These examples demonstrate Phillip's (and some, but certainly not all, other colonists') desire to maintain open relations with Aboriginal peoples, to 'conciliate their affections' and 'live in amity and kindness with them' as per his instructions from the King in 1787.[17]

Phillip's table

Let us return now to Phillip's own table.

Phillip's table was shared with naval and military officers, and as more ships arrived from 1790, distinguished guests, ship's captains and their wives. Despite the tyranny of distance and seemingly rudimentary living conditions, it provided an opportunity to maintain social practices 'in a brief re-enactment of the life they had left behind' in England.[18] The powerful cultural symbolism of the governor's table was recognised by colonists and Aboriginal community members alike and it was a matter of note to some who was entertained there. Lieutenant Ralph Clark, for example, recorded in his diary on 23 February 1790, 'no person dined at the Governors to day more than usual.'[19]

It was not uncommon to find Aboriginal faces at Phillip's table, inlcuding Bennelong, his compatriot Colebee, also Nanbaree, the boy adopted by surgeon White', and on at least one occasion at Parramatta, and perhaps more often in Sydney, Barangaroo, Bennelong's wife. It has been suggested that Barangaroo, notorious for refusing to wear clothes and being 'cap-a-pee in nakedness' as she went about the settlement, maintained this practice at the governor's table.[20] Despite a possible 'enlightened' view of Indigenous peoples among many colonists at this time, it is extraordinary that this would have occurred at the governor's table without creating scandal or at least drawing comment. Extant primary references to Barangaroo suggest various states of dress at different times, and ‘dining’ experiences at Government House are ambiguous and inconclusive, however I am yet to find a specific reference to nakedness at Phillip's table, except in recent historical interpretations.

Table etiquette

Adoption (or adaptation) of dining etiquette was used as a measure of an Aboriginal person's learnt civility. It was noted, for example, that Bennelong, having returned from England in 1794, 'had certainly not been an inattentive observer of the manners of the people among whom he had lived; he conducted himself with the greatest propriety at table.'[21] Arabanoo, the first Aboriginal man held captive at the governor's house, was at first suspicious of the European-style food, but 'bread he began to relish; and tea he drank with avidity.'[22] Diarists remarked on his deportment and table manners, he learnt to use a napkin 'with great cleanliness and decency,' mastered the art of knife and fork, and displayed great ease at the tea-table, managing his cup and saucer 'as if he had been long accustomed to such entertainment.'[23]

Primary sources and archaeology from the period suggest that Phillip's table was graced with tablecloth, good china and cut glassware brought from England. One account of a dinner held at Government House offers us glimpses of table etiquette and involves a lively interplay between two Aboriginal youths, the aforementioned Nanbaree and Yemmerrawannie [Imeerawanyee], the young man who accompanied Bennelong to England with Phillip in 1792. Their antics no doubt provided great entertainment to the other guests, which included Mrs John (Elizabeth) Macarthur:

This good–tempered lively lad [Imeerawanyee], was become a great favourite with us, and almost constantly lived at the governor's house. He had clothes made up for him; and to amuse his mind, he was taught to wait at table. One day a lady, Mrs. M'Arthur, wife of an officer of the garrison, dined there, as did Nanbaree. This latter, anxious that his countryman should appear to advantage in his new office, gave him many instructions, strictly charging him, among other things, to take away the lady's plate, whenever she should cross her knife and fork, and to give her a clean one. This Imeerawanyee executed, not only to Mrs. M'Arthur, but to several of the other guests. At last Nanbaree crossed his knife and fork with great gravity, casting a glance at the other, who looked for a moment with cool indifference at what he had done, and then turned his head another way. Stung at this supercilious treatment, he called in rage, to know why he was not attended to, as well as the rest of the company. But Imeerawanyee only laughed; nor could all the anger and reproaches of the other prevail upon him to do that for one of his countrymen, which he cheerfully continued to perform to every other person.[24]

All the elements of an eighteenth century menu

[media]As Worgan's description of the King's birthday dinner in 1788 attests, meals were created from a mix of imported provisions and local produce, seemingly with all the elements of an eighteenth century menu – soup, fish, fowl, roasts, pies, ragouts and bread. The colony's first grapes, melons and figs were savoured and a cabbage grown at Rose Hill weighing 26lbs (11.7 kilograms) was sent to the governor in time for Christmas, 1789. The cows that were acquired at the Cape of Good Hope on the First Fleet's voyage escaped in June 1788, so fresh butter and cheese would have been a challenge, but cheesecakes and sauces could be made from goats' or perhaps sheep's milk. Kangaroo and emu were procured with the help of the governor's greyhounds, and turtle, a delicacy in the eighteenth century, came from Lord Howe Island when they could be found.

French cuisine

This repertoire was made all the more palatable with the talents, it appears, of a French cook. Tench mentions Phillip having a French cook when Bennelong asked after him on the day of the governor's spearing at Manly Cove in September 1790:

[Bennelong] had constantly made [the French cook] the butt of his ridicule, by mimicking his voice, gait, and other peculiarities, all of which he again went through with his wonted exactness and drollery.[25]

The notion of enjoying French cuisine in such a remote place, renowned for meagre rations, hunger and famine, is fascinating to the gastronomic historian. Phillip spent many years in France, including time pursuing business interests in Flanders, so it is not surprising that he may have developed a taste for French style cuisine. Phillip's personal servant, Bernard de Maliez, appears to have been from Flanders, so there may have been a historical connection with him or his family.

Some scholars have suggested that Maliez was the cook to whom Tench refers. Writing in his diary during a local expedition in 1788, Surgeon White referred to a meal package that was supplied by the governor's steward, so it is possible that cooking was one of his duties.[26] Other authors have suggested that Bennelong and Maliez shared quarters in an upstairs room in Government House.[27] But unless Tench had his wires crossed, the Frenchman that Bennelong so cheekily ridiculed could not have been Maliez, as the two should never have met. Maliez died in August 1789, some three months before Bennelong was originally captured.[28]

The identity of Phillip's French cook remains a mystery, as does much of the more personal details of day-to-day life at Government House, but the few references we do have constitute a tantalising amuse bouche.

This essay is based on a paper originally presented at The first governor – A bicentenary symposium on Arthur Phillip, held at the Museum of Sydney on the site of first Government House on 5 September 2014 by Sydney Living Museums to commemorate the bicentenary of Arthur Phillip’s death

References and further reading:

Bradley, William. A Voyage to New South Wales, December 1786–May 1792, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Safe 1/14

Campbell, James, Letter from Captain James Campbell to Lord Ducie, 12 July 1788, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, MLMSS 5366/ Safe 1/123

Clark, Ralph. The Journal and Letters of Lt Ralph Clark 1787–1792, Edited by Paul G Fidlon and RJ Ryan, Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981.

Collins, David, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1], London: T Cadell Jun and W Davies, 1798.

Hunter, John, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island, London: John Stockdale, 1793.

Tench, Watkin, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789, London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793.

Watling, Thomas, Letters from an Exile at Botany-Bay, to his Aunt in Dumfries: giving a particular account of the settlement of New South Wales, with the customs and manners of the inhabitants, Penrith, Scotland: Ann Bell, 1794.

White, John, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales, London: J Debrett, 1790.

Worgan, George B, Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon 1788, Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales in association with Library of Australian History, 1978.

SECONDARY

Clarkson, Janet, Food History Almanac: Over 1300 Years of World Culinary History, Culture and Social Influence, Lanham, Marylan: Rowman and Littlefield, 2013.

Clendinnen, Inga, Dancing with Strangers, Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 2005.

Cobley, John, Sydney Cove 1791–1792, Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1963.

Currey, John, David Collins: A Colonial Life. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2000.

Gammage, Bill, The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia, Allen and Unwin, 2011.

Karskens, Grace, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney, Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2009.

Keneally, Thomas, Australians, Origins to Eureka, Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin Australia, 2009.

Low, Tim, 'Foods of the First Fleet: Convict Foodplants of Old Sydney Town' Australian Natural History 22, no 7 (1987–1988): 292–97.

Santich, Barbara, Looking for Flavour, Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press. 1986.

Smith, Keith Vincent, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora: Sydney Cove 1788–1792, East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press 2001.

Notes

[1] George B Worgan, Journal of a First Fleet Surgeon 1788 (Sydney: Library Council of New South Wales in association with Library of Australian History, 1978), 34, 35

[2] James Campbell, Letter from Captain James Campbell to Lord Ducie, 12 July 1788, State Library of New South Wales (A1517005 / Safe 1/123 / MLMSS 5366) (Mitchell Library)

[3] John Cobley, 'Letter dated November 24, 1791,' author unknown, Sydney Cove 1791–1792 (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1963) 167

[4] David Collins, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] (London: T Cadell Jun and W Davies, 1798)

[5] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 42

[6] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 44

[7] Barbara Santich, Looking for Flavour (Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press 1996), 43

[8] ‘The First (or Territorial) Seal of New South Wales of 1790–1817,’ Office of Environment and Heritage New South Wales website, http://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/Heritage/research/heraldry/firstseal.htm, viewed 9 June 2015

[9] Aboriginal population numbers are not known. For further information see 'Aboriginal Sydney,' Sydney Barani website, http://www.Sydneybarani.com.au/sites/aboriginal–people–and–place/ viewed 9 June 2015 or 'Population,' History of Western Sydney, Western Sydney Libraries Local Studies website, http://www.westernsydneylibraries.nsw.gov.au/westernsydney/population.html, viewed 9 June 2015

[10] David Collins, September 1796,' An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] (London: T Cadell Jun and W Davies, 1798), 557

[11] Tim Low, 'Foods of the First Fleet: Convict Foodplants of Old Sydney Town,' Australian Natural History 22, no 7 (1987–1988): 292–97

[12] For more detail see Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2009) 387–392

[13] For more information on the spearing of Governor Phillip by an Aboriginal warrior see Keith Vincent Smith, 'Woollarawarre Bennelong,' Dictionary of Sydney, http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/woollarawarre_bennelong, viewed online 9 June 2015 or Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2009) 383–385

[14] Watkin Tench, November 1790, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 73

[15] For example, John Hunter, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (London: John Stockdale, 1793), 480–487

[16] Thomas Watling, Letters from an Exile at Botany-Bay, to his Aunt in Dumfries: giving a particular account of the settlement of New South Wales, with the customs and manners of the inhabitants (Penrith, Scotland: Ann Bell, 1794)

[17] Instructions from the King, April 25, 1787, Historical Records of Australia, Series I: Governors' Despatches to and from England, edited by Frederick Watson (Sydney: The Library Committee of the Commonwealth Parliament, 1914), 13.

[18] John Currey, David Collins: A Colonial Life (Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2000)

[19] Ralph Clark, February 23, 1790, The Journal and Letters of Lt Ralph Clark 1787–1792, edited by Paul G Fidlon and RJ Ryan (Sydney: Australian Documents Library, 1981)

[20] Grace Karskens, The Colony: A History of Early Sydney (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2009) 401; Inga Clendinnen, Dancing with Strangers (Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 2005), 143

[21] David Collins, November 1794, An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] (London: T Cadell Jun and W Davies, 1798), 440

[22] Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 14

[23] John Hunter, May 1789, An Historical Journal of the Transactions at Port Jackson and Norfolk Island (London: John Stockdale, 1793), 132;; Watkin Tench, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 11

[24] Watkin Tench, note, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 86

[25] Watkin Tench, September 1790, A Complete Account of the Settlement at Port Jackson 1789 (London: G Nicol and J Sewell, 1793), 57

[26] John White, Journal of a Voyage to New South Wales (London: J Debrett, 1790), 145

[27] Keith Vincent Smith, Bennelong: The Coming in of the Eora: Sydney Cove 1788–1792 (East Roseville, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press 2001), 39–40, 51 cited in Mary Casey, 'Chapter 11: Research Design,'Archaeological Investigation Conservatorium Site, Macquarie Street, Sydney Volume II: History and Archaeology for NSW Department of Public works and Services (Marickville, NSW: Casey & Lowe Pty Ltd, July 2002), 5; Thomas Keneally, Australians, Origins to Eureka (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin Australia, 2009), 231

[28] 'Deaths 1789 Sydney and Norfolk Island,' Australian History Research, http://www.australianhistoryresearch.info/deaths-1789-sydney-and-norfolk-island/, viewed 9 June 2015